[/caption]

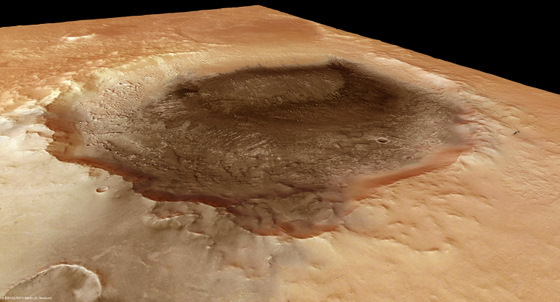

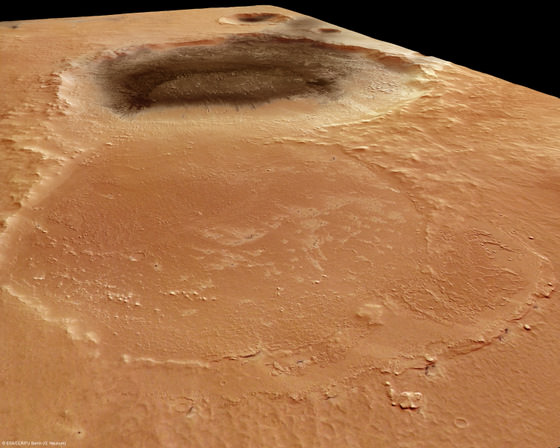

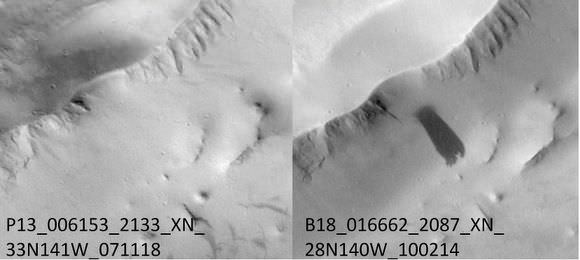

Mission planners have narrowed the field for possible launch dates for NASA’s next generation rover to Mars, the Mars Science Laboratory, nicknamed Curiosity. Taking into account orbital mechanics, planetary alignment, and communications issues, MSL’s launch will occur between Nov. 25 and Dec. 18, 2011, with landing will taking place between Aug. 6 and Aug. 20, 2012. The actual landing site is still being decided, between four different locations on Mars (read about the four sites here.)

“The key factor was a choice between different strategies for sending communications during the critical moments before and during touchdown,” said Michael Watkins, mission manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. “The shorter trajectory is optimal for keeping both orbiters in view of Curiosity all the way to touchdown on the surface of Mars. The longer trajectory allows direct communication to Earth all the way to touchdown.”

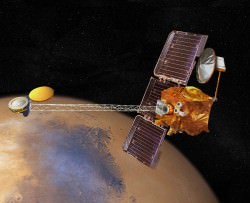

Landing on Mars is always very difficult, and NASA has put a high priority on communication during Mars landings, especially after a landing failure in 1999. Therefore, the flight schedule allows for favorable positions for the Mars Odyssey and the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, currently orbiting Mars, which can both obtain information during descent and landing of MSL.

The simplicity of direct-to-Earth communication from Curiosity during landing has appeal to mission planners, but the direct-to-Earth option allows a communication rate equivalent to only about 1 bit per second, while the relay option allows about 8,000 bits or more per second.

“It is important to capture high-quality telemetry to allow us to learn what happens during the entry, descent and landing, which is arguably the most challenging part of the mission,” said Fuk Li, manager of NASA’s Mars Exploration Program at JPL. “The trajectory we have selected maximizes the amount of information we will learn to mitigate any problems.”

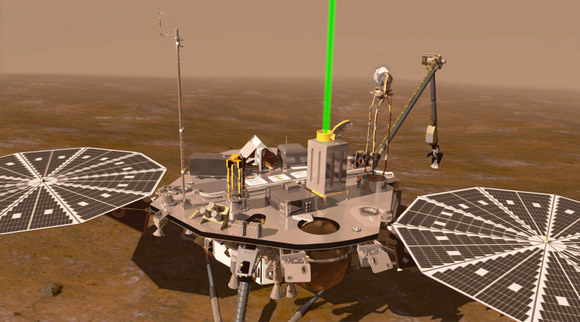

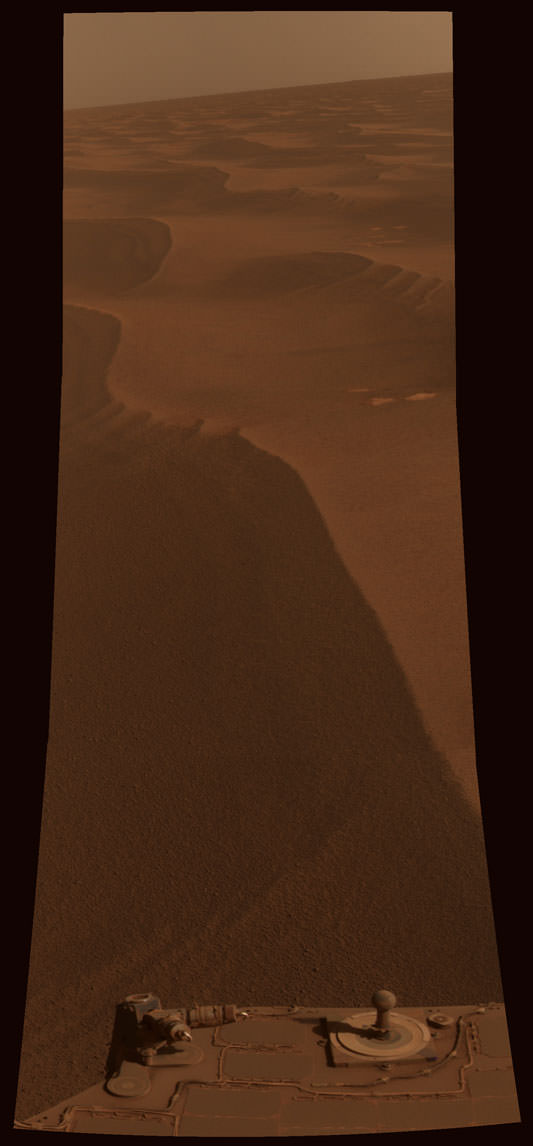

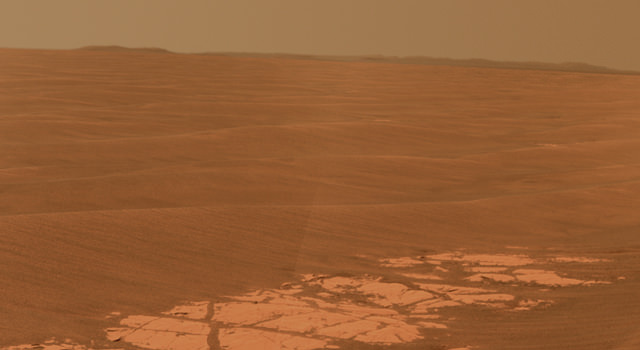

Curiosity will use several innovations during entry, descent and landing in order to hit a relatively small target area on the surface and set down a rover too heavy for the cushioning air bags used in earlier Mars rover landings. MSL will use employ of the largest parachutes ever used in a space mission to land a car-sized rover on the Red Planet. Most interesting is the final phase of landing, where a “sky-crane,” a rocket-powered descent stage will lower Curiosity on a tether for a wheels-down landing directly onto the surface.

Even though Curiosity won’t be communicating directly with Earth at touchdown, data about the landing will reach Earth promptly. Odyssey will be in view of both Earth and Curiosity, in position to immediately forward to Earth the data stream it is receiving during the touchdown. Odyssey performed this type of “bent-pipe” relay during the May 25, 2008, arrival of NASA’s Phoenix Mars Lander.

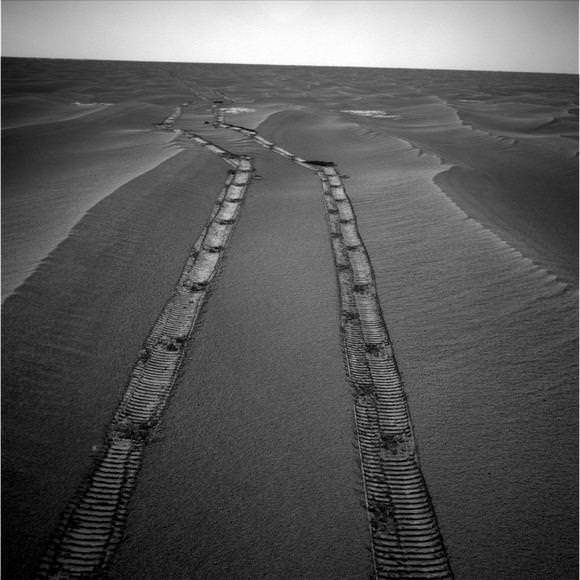

Curiosity will rove extensively on Mars, carrying an analytical laboratory and other instruments to examine a carefully selected landing area. It will investigate whether conditions there have favored development of microbial life and its preservation in the rock record. Plans call for the mission to operate on Mars for a full Martian year, which is equivalent to two Earth years.

More information about NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory.

Source: JPL