[/caption]

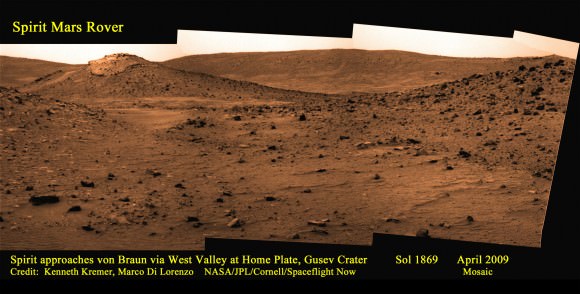

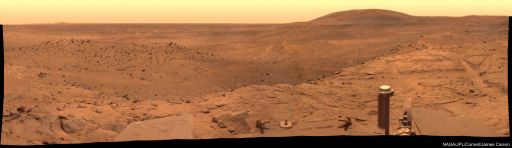

Scientists say that the Arctic region studied by Phoenix lander may be a favorable environment for microbes. Just-right chemistry and periods where thin films of liquid water form on the surface could make for a habitable setting. “Not only did we find water ice, as expected, but the soil chemistry and minerals we observed lead us to believe this site had a wetter and warmer climate in the recent past — the last few million years — and could again in the future,” said Phoenix Principal Investigator Peter Smith of the University of Arizona, Tucson.

The Phoenix science team released four papers today after spending months interpreting the data returned by the lander during its 5-month mission.

The most surprising finding was perchlorate in the Martian soil. This Phoenix finding caps a growing emphasis on the planet’s chemistry, said Michael Hecht of from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who led a paper about Phoenix’s soluble-chemistry findings.

“The study of Mars is in transition from a follow-the-water stage to a follow-the-chemistry stage,” Hecht said. “With perchlorate, for example, we see links to atmospheric humidity, soil moisture, a possible energy source for microbes, even a possible resource for humans.”

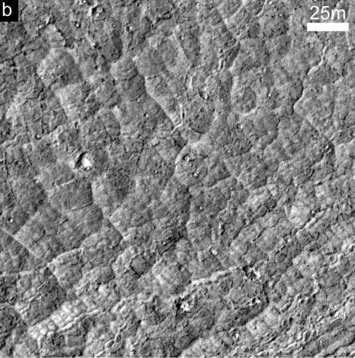

Perchlorate, which strongly attracts water, makes up a few tenths of a percent of the composition in all three soil samples analyzed by Phoenix’s wet chemistry laboratory. It could pull humidity from the Martian air. At higher concentrations, it might combine with water as a brine that stays liquid at Martian surface temperatures. Some microbes on Earth use perchlorate as food. Human explorers might find it useful as rocket fuel or for generating oxygen.

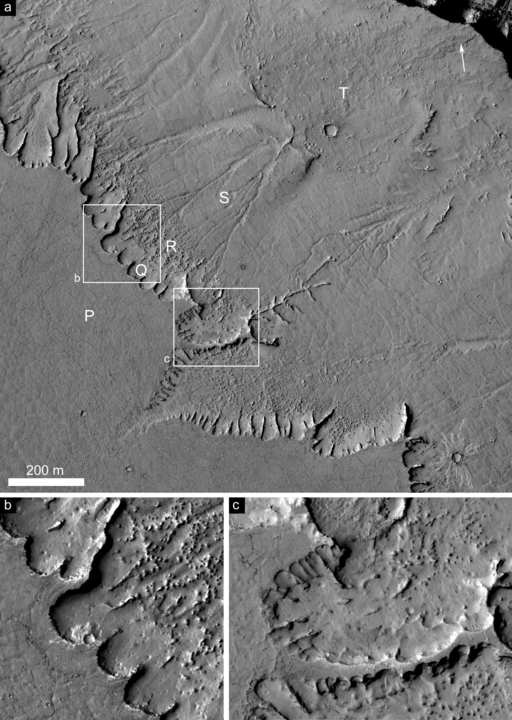

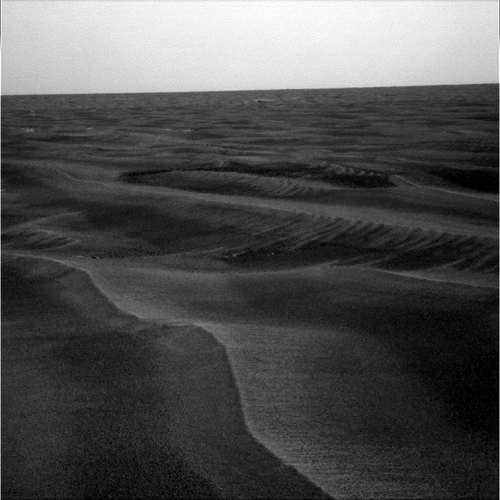

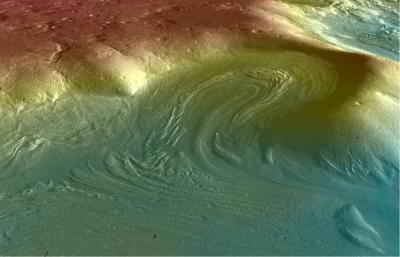

A paper about Phoenix water studies, led by Smith, cites clues supporting an interpretation that the soil has had films of liquid water in the recent past. The evidence for water and potential nutrients “implies that this region could have previously met the criteria for habitability” during portions of continuing climate cycles, these authors conclude.

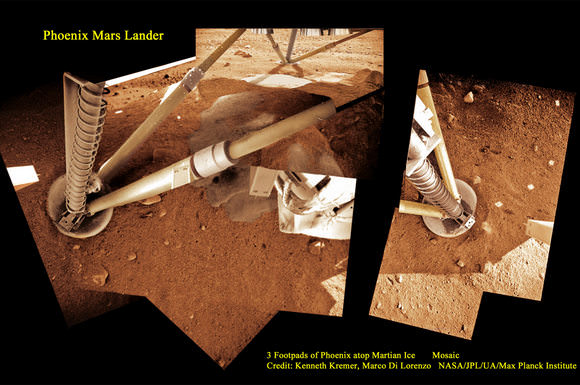

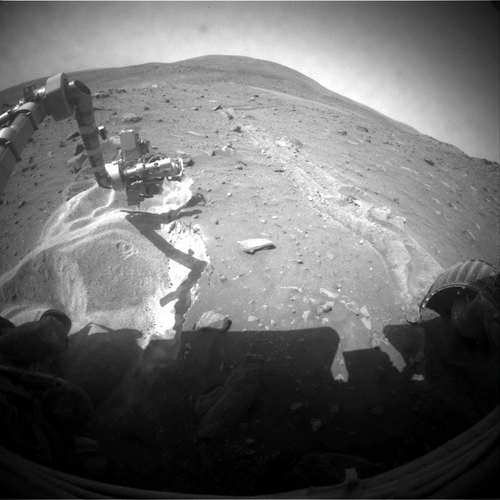

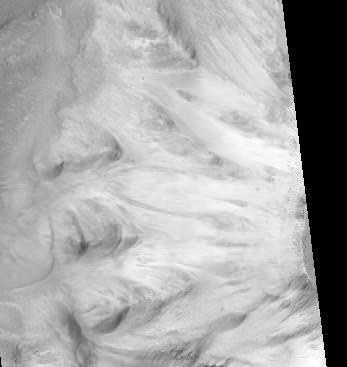

Phoenix dug down with its scoop and found ice just under the surface of Mars. “We wanted to know the origin of the ice,” Smith said. “It could have been the remnant of a larger polar ice cap that shrank; could have been a frozen ocean; could have been a snowfall frozen into the ground. The most likely theory is that water vapor from the atmosphere slowly diffused into the surface and froze at the level where the temperature matches the frost point. We expected that was probably the source of the ice, but some of what we found was surprising.”

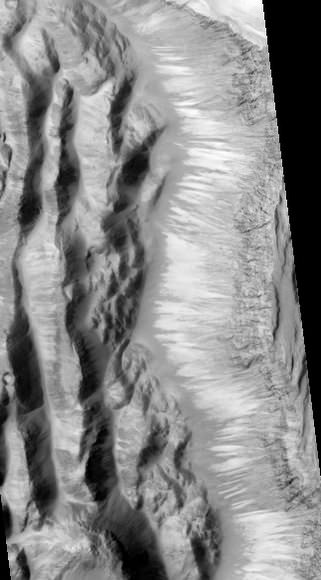

Evidence that the ice in the area sometimes thaws enough to moisten the soil comes from finding calcium carbonate in soil heated in the lander’s analytic ovens or mixed with acid in the wet chemistry laboratory. Another paper from a team led by University of Arizona’s William Boynton report that the amount of calcium carbonate “is most consistent with formation in the past by the interaction of atmospheric carbon dioxide with liquid films of water on particle surfaces.”

The new reports leave unsettled whether soil samples scooped up by Phoenix contained any carbon-based organic compounds. The perchlorate could have broken down simple organic compounds during heating of soil samples in the ovens, preventing clear detection.

The heating in ovens did not drive off any water vapor at temperatures lower than 295 degrees Celsius (563 degrees Fahrenheit), indicating the soil held no water adhering to soil particles. Climate cycles resulting from changes in the tilt and orbit of Mars on scales of hundreds of thousands of years or more could explain why effects of moist soil are present.

Phoenix launched in August 2007and landed in May, 2008. Phoenix ended communications in November 2008 as the approach of Martian winter depleted energy from the lander’s solar panels.

Sources: JPL, EurekAlert, Spaceflightnow.com