After multiple delays, SpaceX recently announced that the inaugural flight of their Falcon Heavy rocket would take place this Tuesday, February 6th, 2018. This rocket, which is the heaviest launch vehicle in the SpaceX fleet (and the most powerful operational rocket in the world right now), is not only central to the company’s vision of reusable rockets, but also to Musk’s long-term vision of sending humans to Mars.

As a result, people all over the world have been tuning in to watch the coverage of the event, and eagerly waiting to see the rocket take off before its launch window closes at 04:00 pm (PST) this afternoon. In keeping with Musk’s habit of sending interesting payloads into space, the rocket will be carrying his cherry-red Tesla Roadster, with the goal of depositing it into a stable orbit around Mars.

According to previous statements made by Musk, the plan calls for the Falcon Heavy to launch the Roadster on a Hohmann Transfer trajectory, an orbital maneuver where a satellite or spacecraft is transferred from one circular orbit to another. After being placed in an elliptical orbit between Earth and Mars, the Roadster would be picked up by Mars’ gravity and remain in orbit around it for (according to Musk) up to a billion years!

To add to the peculiarity of the mission payload, Musk has also been clear that he wants the car to be playing “Space Oddity” – the famous song written and performed by the late and great David Bowie – as its launched into space. This classic song recently got a shot in the arm thanks to Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield, who performed a rendition of the song while still serving as the commander of Expedition 35 aboard the International Space Station.

But unlike Hadfield’s more positive rendition of the song (which you can watch above), in which the astronaut (Major Tom) does NOT die, Musk’s Roadster will be belting out this tune in its original form. One can only assume that he’s not a particularly superstitious man, or just has a very quirky sense of humor. Considering that a previous payload consisted of a wheel of cheese, I think we know the answer!

Musk confirmed that the launch would take place at 0:130 pm EST (10:30 am PST) in a tweet he posted yesterday, where he stated:

All systems remain green for launch at 1:30pm EST tomorrow

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) February 5, 2018

This was followed by an additional tweet posted at 07:59 am PST, which indicated that the launch was still on. However, Musk announced that there would be a minor delay at 09:02 am PST, which was apparently weather-related:

“About 2.5 hours to T-0 for Falcon Heavy. Watch sim for highlight reel of what we hope happens. Car actually takes 6 months to cover 200M+ miles to Mars”

“Upper atmosphere winds currently 20% above max allowable load. Holding for an hour to allow winds to diminish.

#FalconHeavy“

In addition, changes were seen in the countdown clocks run by the US Air Force’s Eastern Range operations. This pushed the launch from its original time of 01:30 pm to 03:19 pm EST (12:19 am PST), and then led to the count being placed on hold. By 10:52 am PST this morning, the launch clock resumed and Musk indicated that the takeoff would commence at 3:45 pm EST (12:45 PST).

This was followed by the SpaceX ground crew commencing procedures to fuel the rocket at about 11:22 am PST.

Launch auto-sequence initiated (aka the holy mouse-click) for 3:45 liftoff #FalconHeavy

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) February 6, 2018

Naturally, there has been plenty of speculation about the possible outcome of the mission. Max Fagin, an aerospace engineer from Colorado and a space camp alumni, is one such person. In a video he uploaded to his Youtube channel yesterday (Feb. 5th, 2018), he clarified what the proposed launch entails and offered his thoughts on what will likely happen to the Roadster once its sent into space.

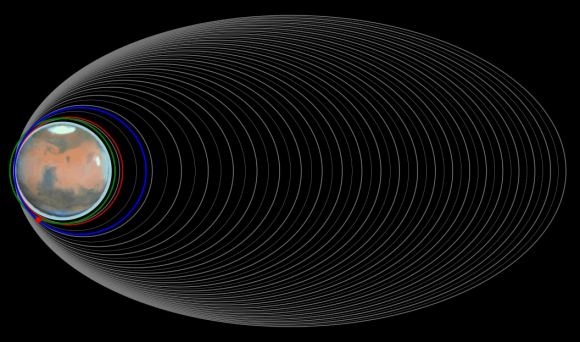

Addressing Musk’s stated goal of a Hohmann Transfer that would put the roadster into Mars’ orbit, he indicated that Musk must have been oversimplifying because there’s no reason to launch a spacecraft on such a trajectory right now. This is due to the fact that this maneuver only makes sense when Earth and Mars are at the closest points in their orbits to each other – aka. when Mars is at opposition.

This is not the case at present, and won’t be again until April-May of this year. At that point, Earth and Mars will be the closest they have been to each other since the year 2000, and will not be in such a perfect opposition again until 2033. As a result, says Fagin, a “true Hohmann Transfer launched from Earth to Mars right now would take the Roadster no closer than 90 million km from Mars – 0.6 times the distance from Earth to the Sun.”

Having said all that, here is what Fagin thinks is actually going to happen:

“Given how light the Roadster is, and given how powerful the Falcon Heavy is, I suspect Falcon heavy is going to impart a little extra delta-v to the Roadster, beyond what would be required for a minimum-energy Hohmann Transfer. This would allow the Roadster to get as close to Mars as SpaceX wanted sometime in October of 2018.”

According to Fagin’s analysis, the Roadster would still not be able to remain in the same orbit of Mars for a billion years, which was Musk’s stated goal. But it would achieve a more stable orbit than a basic Hohmann Transfer would accomplish. In that scenario, the orbit would be perturbed by close encounters with Earth, and the Roadster might eventually come back to Earth.

In other words, the plan may be more complicated than originally stated, but could be largely successful all the same. Come what may, there is no shortage of people who want to see this rocket successfully take off! After all, it’s not only SpaceX’s future that is riding on the outcome of this launch, but perhaps even the future of space exploration itself. Cheaper costs and restored launch capability, that’s what it’s all about!

Barring any further delays, which will push the launch back until tomorrow, the launch will be taking place in T-minus 20 minutes (as of the penning of this article)! In the meantime, be sure to check out SpaceX’s live coverage of the event, which begins today (Tuesday, Feb. 6th) at

Further Reading: SpaceX webcast, SpaceX, Twitter (Elon Musk), Orlando Sentinel

![The Viking 2 lander captured this image of itself on the Martian surface. The Viking Landers were the last missions to directly look for life on Mars. By NASA - NASA website; description,[1] high resolution image.[2], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17624](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/608px-Viking2lander1-580x458.jpg)