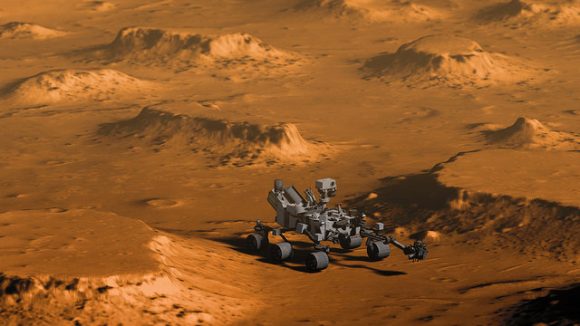

We all love the ‘selfies’ the Curiosity rover takes of itself sitting on Mars. We love them because it’s so amazing to see a human-made object on another world, and these images give us hope that one day we might have pictures of ourselves standing on the surface of the Red Planet.

But wouldn’t it be great if we see Curiosity ‘in action’ on Mars, and be like a fly on a rock, watching the rover roll past us?

Thanks to creative artist Seán Doran, we can do just that. Take a look at this absolutely amazing video Seán created, using real images of the Mars landscape from Curiosity and the HiRISE camera on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, with a GCI Curiosity roving around.

Please note that Curiosity doesn’t actually move this fast, as in the video it is going about 8 kph, whereas in reality, the rover travels at a top speed of about .16 kph. But still, this is just fantastic!

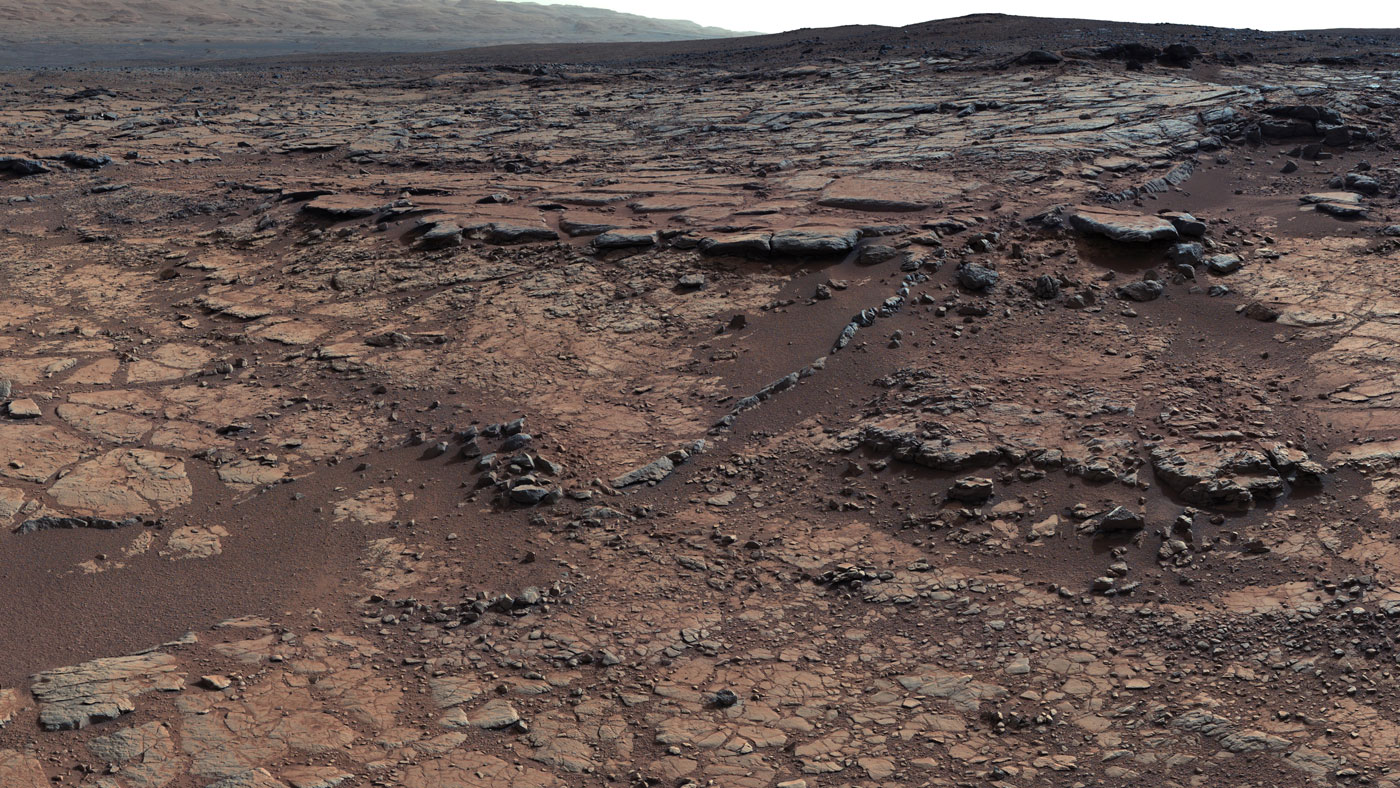

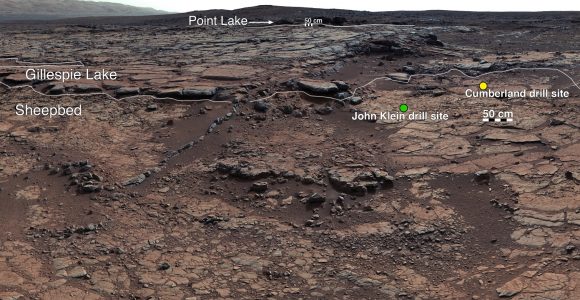

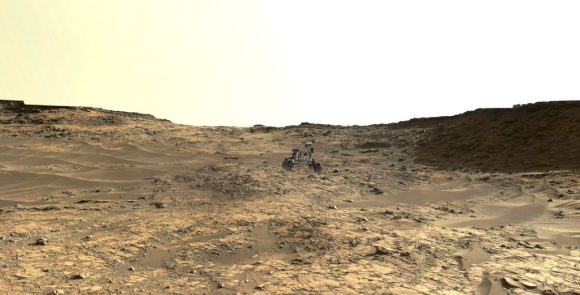

“As much as I enjoy looking at the images from Mars, it is difficult to get a real sense of the scene as there is no obvious Earthly scale cue,” Seán told Universe Today via email. “No trees, plants, buildings or humans. So, I decided to put Curiosity into her own photographs to help us relate to them.”

Seán has provided a glimpse at how to do this, and says there are two ways of achieving these results.

One, is the easy way:

Create a photomosaic of a scene where tracks are present.

https://flic.kr/p/FnJqxE

Render a 3D model of Curiosity to the same relative angle of the tracks and composite this into the image.

https://flic.kr/p/GfSDzm

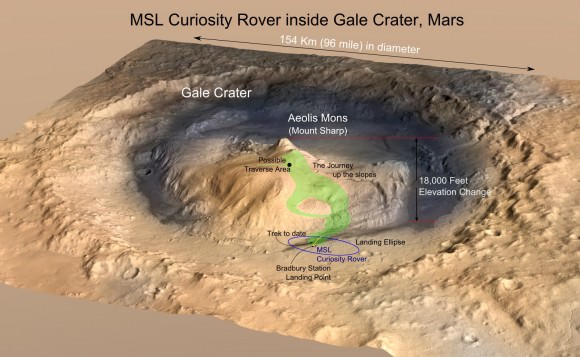

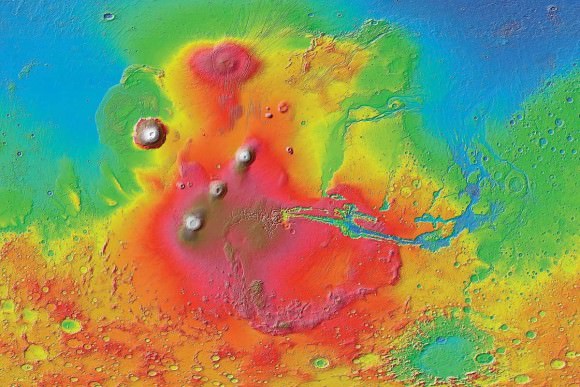

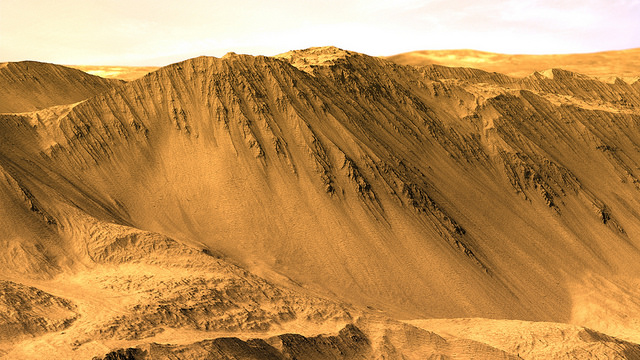

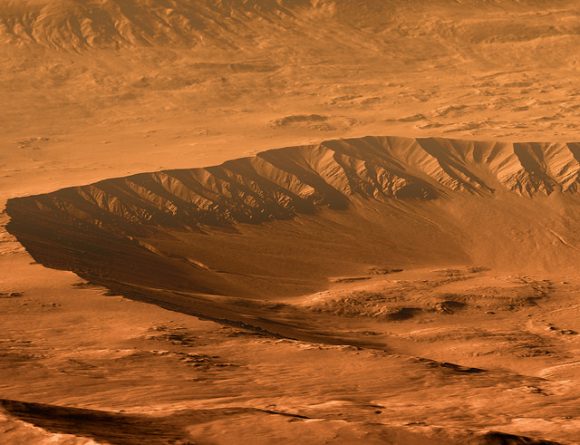

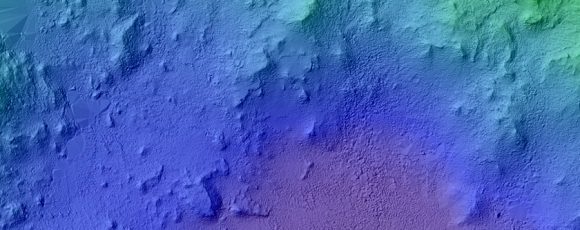

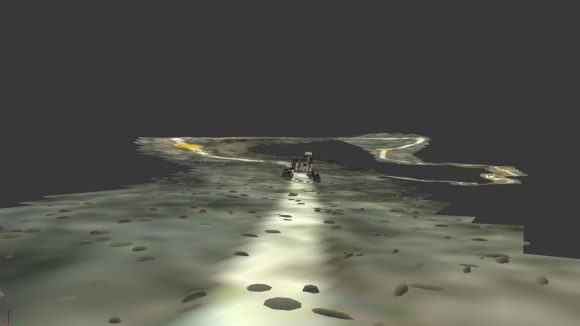

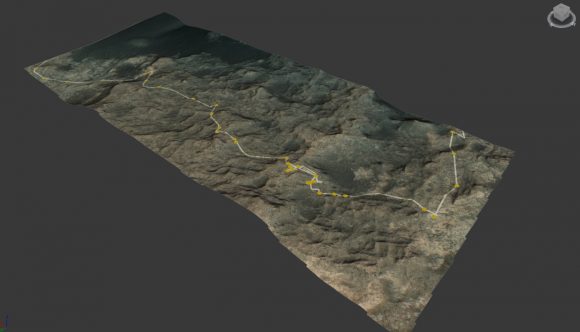

Or, there’s the hard way, a process which allows Seán to ‘drive’ Curiosity across the field of view of any photomosaic the rover has taken, whether there are tracks or not. This process involves using the what are called Digital Terrain Model (DTM) data from HiRISE, which provide elevation and terrain information (more info about DTMs in our recent article here) and by mapping with a virtual camera.

Here is an example:

https://flic.kr/p/JefsHi

You can see Doran’s work on this model in Sketchfab, which he has been putting together for several months.

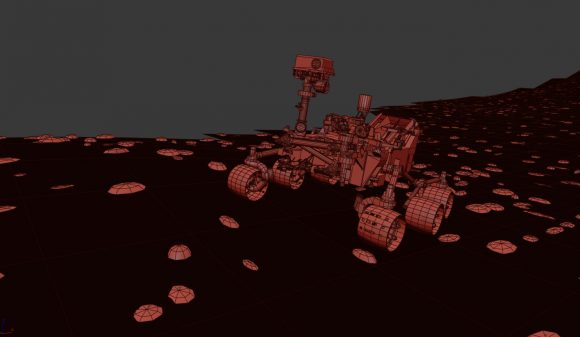

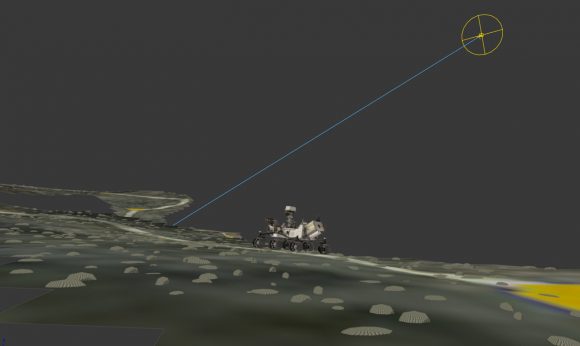

But to make everything realistic, your virtual rover needs to be the right size and even the right weight.

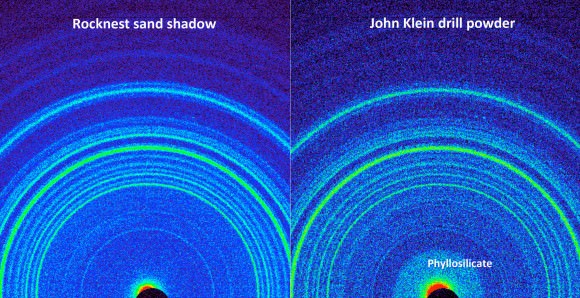

“It is critical to accurately determine the size of Curiosity in the virtual scene and this is done by comparing images of the rover taken by HiRISE and making sure they match,” Seán said. “By matching the viewpoint and the field of view it is possible to derive an accurate scale for Curiosity at any point in the scene.”

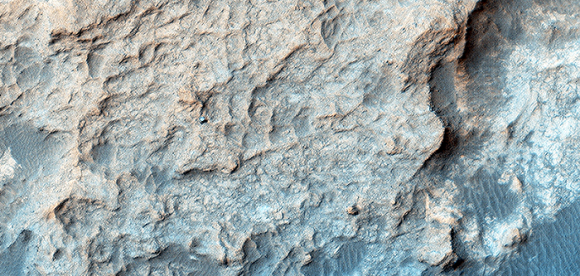

So by using this view from HiRISE of Curiosity sitting on the Naukluft Plateau:

And then using Curiosity’s image of the same location, he can put a true-to-size rover in the image:

Then he ‘builds’ the route and terrain to make it even more realistic.

“Before I drive Curiosity I need to build a rocky collision course so she can physically interact with the environment,” he said. “This really helps to sell the final shot.”

Then Seán builds a ‘car rig’ for Curiosity and drives her across the scene, in line with the actual route taken. Seán says good choices for doing this are using MadCar and DriveMaster for 3DS Max.

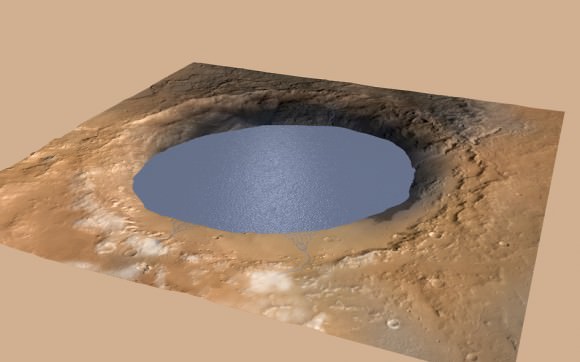

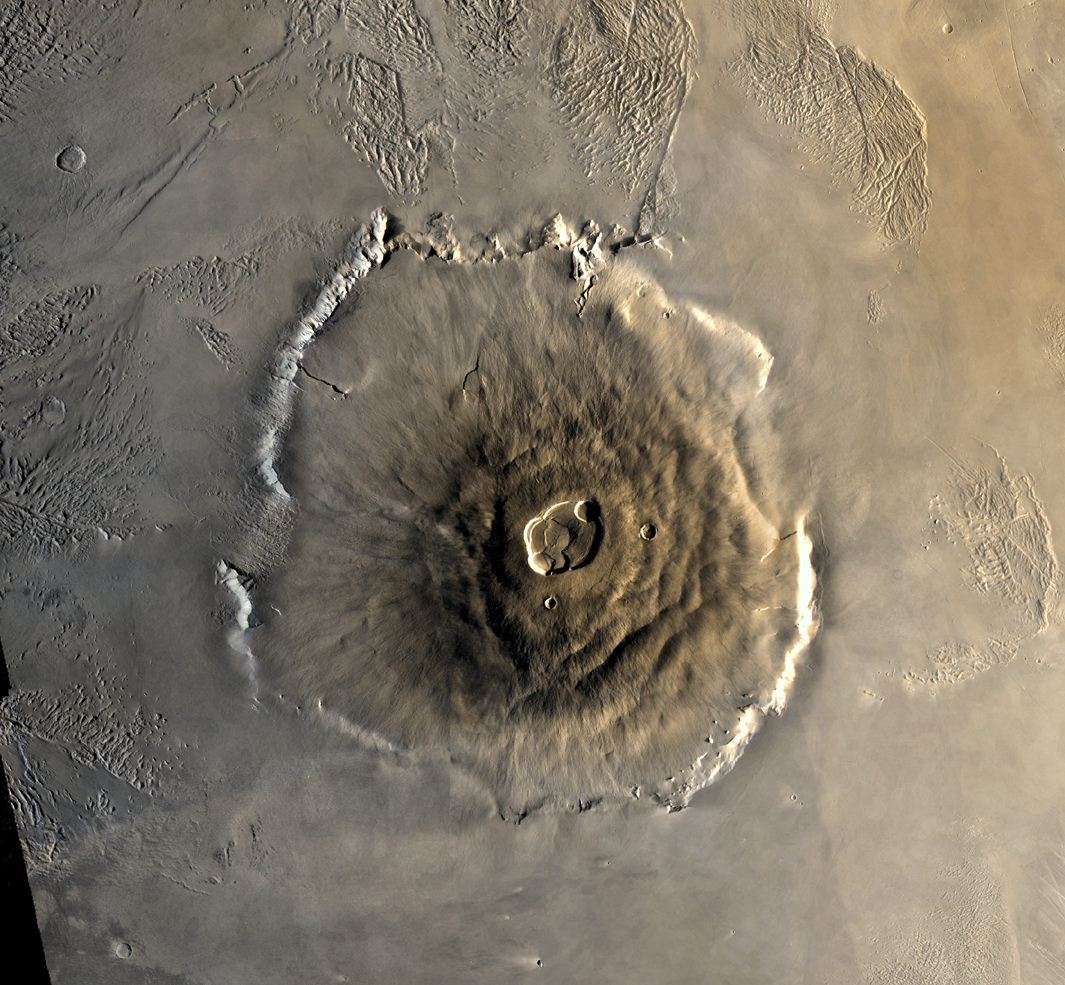

Then he takes a look at the big picture, taking the HiRISE image of the area and using the DTM files to create elevation and texture, and adds the route the rover will take so he knows where to ‘drive’ the rover:

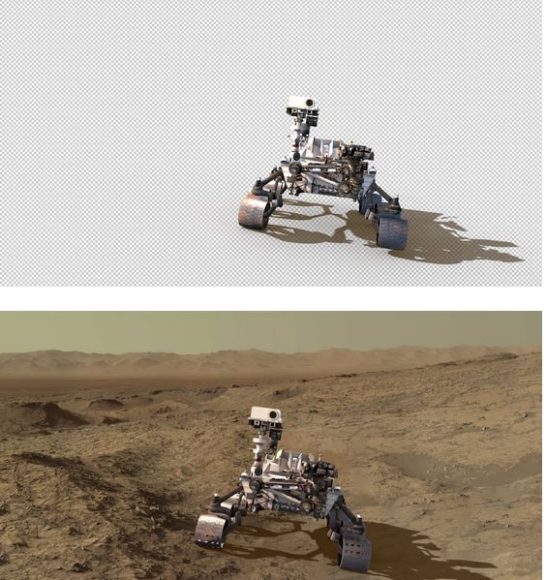

Then comes the time-consuming part, where once he has a good animation, he needs to render out each shot, plus he matches the Sun position so the virtual shadows cast will match those in the photomosaic. (Wow!)

“I render separate passes for the background photomosaic and the foreground Curiosity,” Seán explained. “The HiRISE physics model is rendered with a Shadow Matte material which only catches shadows, this enables the rover to be easily blended in the final stage of the build.”

Then, everything is brought together in Adobe After Effects, where further image processing is used to blend both render elements together.

We thank Seán Doran not only for completing this intricate process we can all enjoy, but for sharing the details!

“There is nothing trivial about building these assets, they are made out of fascination with the material and desire to communicate the excitement of being ‘present’ on another planet,” Seán said. “But I think it a great way to help people engage with such an exciting mission.”

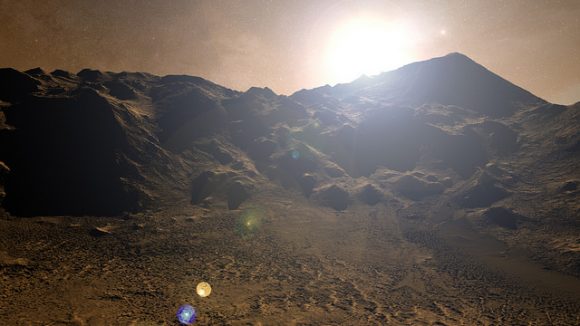

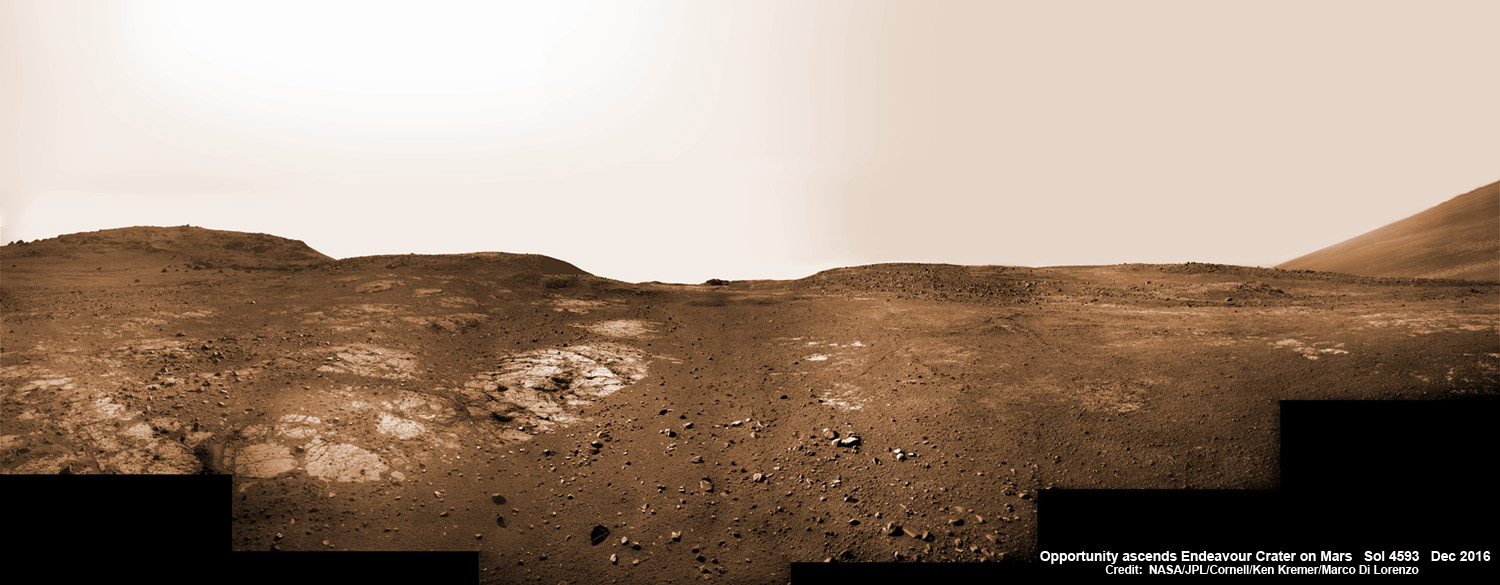

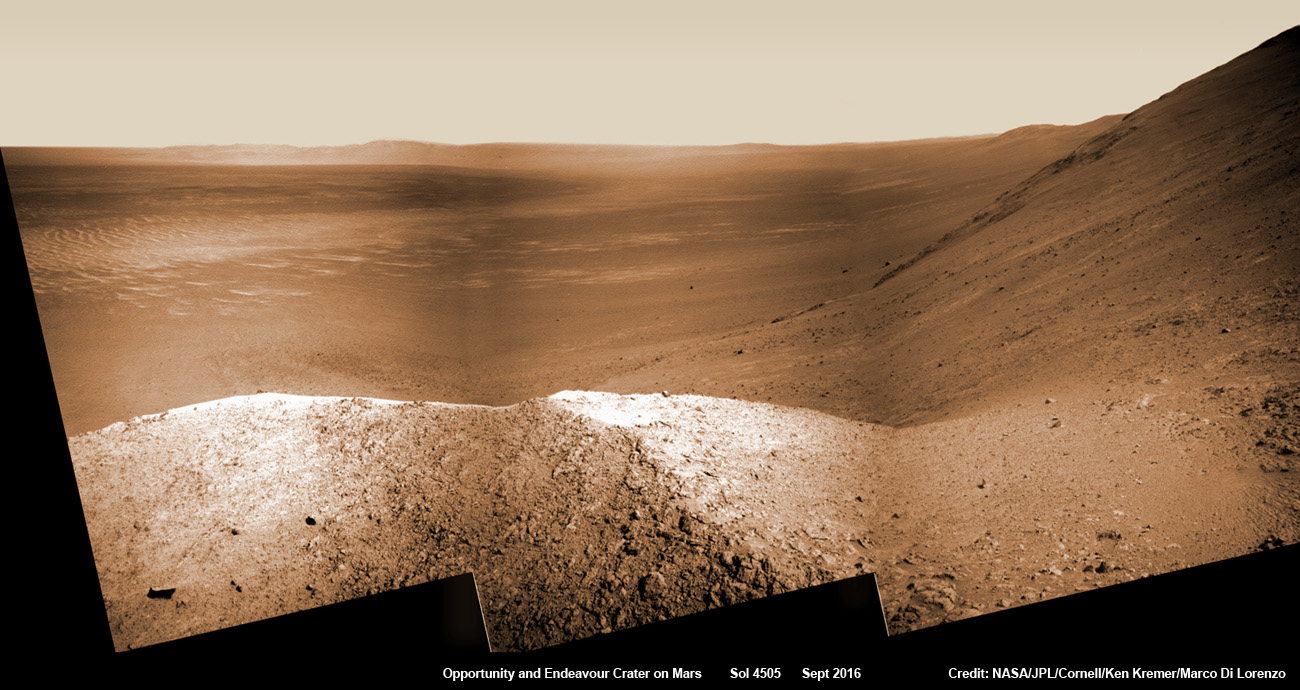

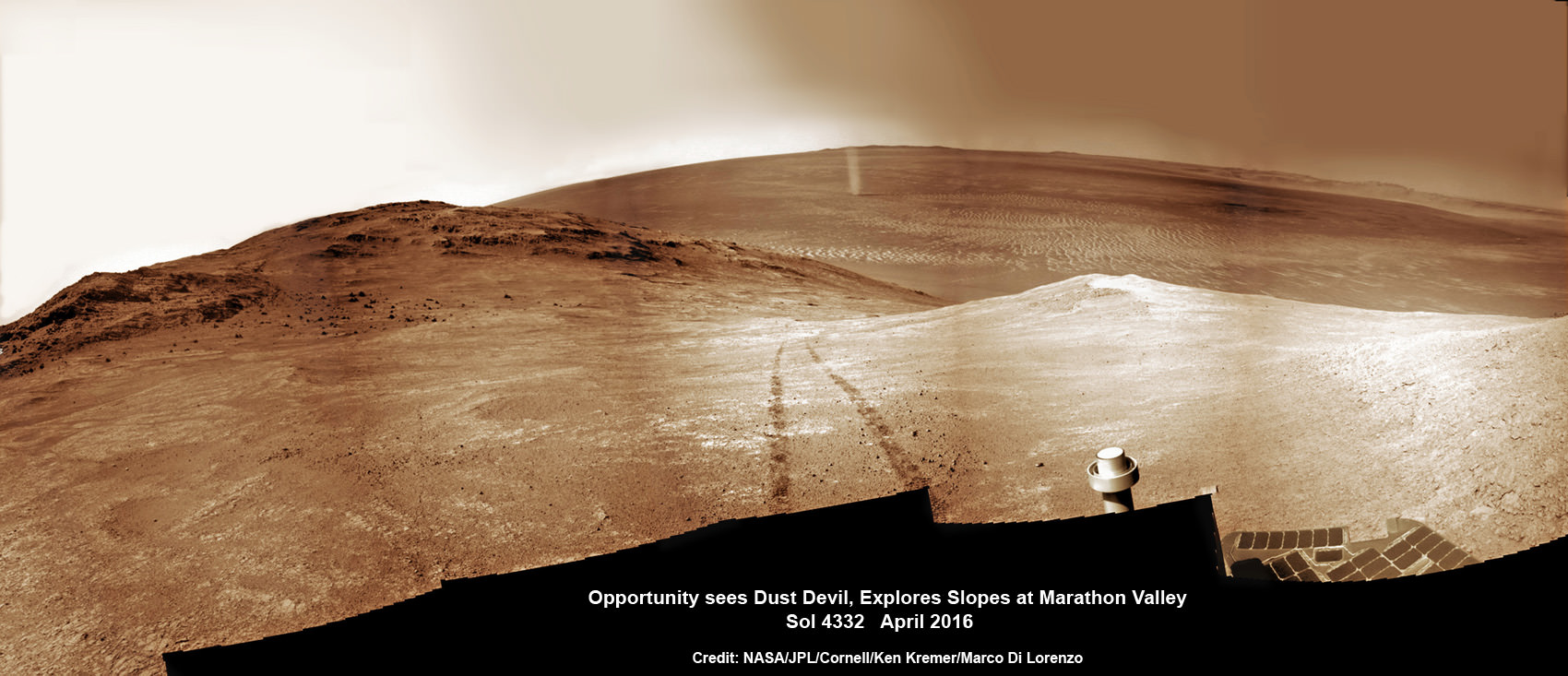

More views from the video:

https://flic.kr/p/PUAbxN

https://flic.kr/p/Q1isdt

You can see many more images of Curiosity from Doran’s Flickr account, and his Sketchfab account has a lot of VR-ready content to explore.

Doran’s Gigapan account has extremely high resolution images of Gale Crater built using HiRISE data.

And to see his latest work and follow what he is currently working on, follow Seán Doran on Twitter: @_TheSeaning