It’s time for us to go back and catch up with all of the projects, news stories, weird star systems, and other topics that we need updates on!

Continue reading “Astronomy Cast Ep. 400: State of the Universe”

NASA Completes Welding on Lunar Orion EM-1 Pressure Vessel Launching in 2018

In a major step towards flight, engineers at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans have finished welding together the pressure vessel for the first Lunar Orion crew module that will blastoff in 2018 atop the agency’s Space Launch System (SLS) rocket.

This Orion is going to the Moon and back.

The 2018 launch of NASA’s Orion on an unpiloted flight dubbed Exploration Mission, or EM-1, counts as the first joint flight of SLS and Orion, and the first flight of a human rated spacecraft to deep space since the Apollo Moon landing era ended more than 4 decades ago. Continue reading “NASA Completes Welding on Lunar Orion EM-1 Pressure Vessel Launching in 2018”

How Long Is A Day On The Other Planets Of The Solar System?

Here on Earth, we tend to take time for granted, never suspected that the increments with which we measure it are actually quite relative. The ways in which we measure our days and years, for example, are actually the result of our planet’s distance from the Sun, the time it takes to orbit, and the time it takes to rotate on its axis. The same is true for the other planets in our Solar System.

While we Earthlings count on a day being about 24 hours from sunup to sunup, the length of a single day on another planet is quite different. In some cases, they are very short, while in others, they can last longer than years – sometimes considerably! Let’s go over how time works on other planets and see just how long their days can be, shall we?

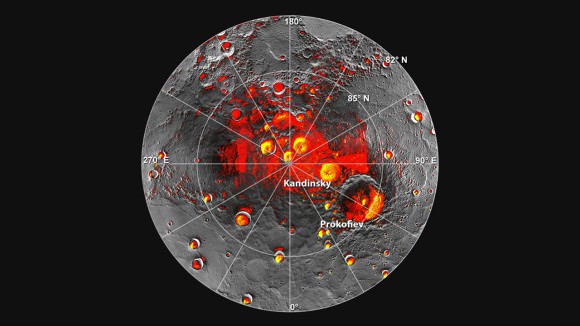

A Day On Mercury:

Mercury is the closest planet to our Sun, ranging from 46,001,200 km at perihelion (closest to the Sun) to 69,816,900 km at aphelion (farthest). Since it takes 58.646 Earth days for Mercury to rotate once on its axis – aka. its sidereal rotation period – this means that it takes just over 58 Earth days for Mercury to experience a single day.

However, this is not to say that Mercury experiences two sunrises in just over 58 days. Due to its proximity to the Sun and rapid speed with which it circles it, it takes the equivalent of 175.97 Earth days for the Sun to reappear in the same place in the sky. Hence, while the planet rotates once every 58 Earth days, it is roughly 176 days from one sunrise to the next on Mercury.

What’s more, it only takes Mercury 87.969 Earth days to complete a single orbit of the Sun (aka. its orbital period). This means a year on Mercury is the equivalent of about 88 Earth days, which in turn means that a single Mercurian (or Hermian) year lasts just half as long as a Mercurian day.

What’s more, Mercury’s northern polar regions are constantly in the shade. This is due to it’s axis being tilted at a mere 0.034° (compared to Earth’s 23.4°), which means that it does not experience extreme seasonal variations where days and nights can last for months depending on the season. On the poles of Mercury, it is always dark and shady. So you could say the poles are in a constant state of twilight.

A Day On Venus:

Also known as “Earth’s Twin”, Venus is the second closest planet to our Sun – ranging from 107,477,000 km at perihelion to 108,939,000 km at aphelion. Unfortunately, Venus is also the slowest moving planet, a fact which is made evident by looking at its poles. Whereas every other planet in the Solar System has experienced flattening at their poles due to the speed of their spin, Venus has experienced no such flattening.

Venus has a rotational velocity of just 6.5 km/h (4.0 mph) – compared to Earth’s rational velocity of 1,670 km/h (1,040 mph) – which leads to a sidereal rotation period of 243.025 days. Technically, it is -243.025 days, since Venus’ rotation is retrograde. This means that Venus rotates in the direction opposite to its orbital path around the Sun.

So if you were above Venus’ north pole and watched it circle around the Sun, you would see it is moving clockwise, whereas its rotation is counter-clockwise. Nevertheless, this still means that Venus takes over 243 Earth days to rotate once on its axis. However, much like Mercury, Venus’ orbital speed and slow rotation means that a single solar day – the time it takes the Sun to return to the same place in the sky – lasts about 117 days.

So while a single Venusian (or Cytherean) year works out to 224.701 Earth days, it experiences less than two full sunrises and sunsets in that time. In fact, a single Venusian/Cytherean year lasts as long as 1.92 Venusian/Cytherean days. Good thing Venus has other things in common With Earth, because it is sure isn’t its diurnal cycle!

A Day On Earth:

When we think of a day on Earth, we tend to think of it as a simple 24 hour interval. In truth, it takes the Earth exactly 23 hours 56 minutes and 4.1 seconds to rotate once on its axis. Meanwhile, on average, a solar day on Earth is 24 hours long, which means it takes that amount of time for the Sun to appear in the same place in the sky. Between these two values, we say a single day and night cycle lasts an even 24.

At the same time, there are variations in the length of a single day on the planet based on seasonal cycles. Due to Earth’s axial tilt, the amount of sunlight experienced in certain hemispheres will vary. The most extreme case of this occurs at the poles, where day and night can last for days or months depending on the season.

At the North and South Poles during the winter, a single night can last up to six months, which is known as a “polar night”. During the summer, the poles will experience what is called a “midnight sun”, where a day lasts a full 24 hours. So really, days are not as simple as we like to imagine. But compared to the other planets in the Solar System, time management is still easier here on Earth.

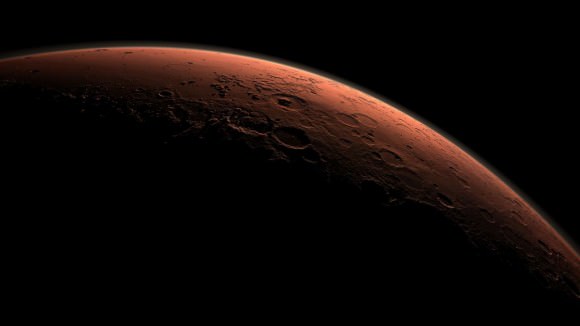

A Day On Mars:

In many respects, Mars can also be called “Earth’s Twin”. In addition to having polar ice caps, seasonal variations , and water (albeit frozen) on its surface, a day on Mars is pretty close to what a day on Earth is. Essentially, Mars takes 24 hours 37 minutes and 22 seconds to complete a single rotation on its axis. This means that a day on Mars is equivalent to 1.025957 days.

The seasonal cycles on Mars, which are due to it having an axial tilt similar to Earth’s (25.19° compared to Earth’s 23.4°), are more similar to those we experience on Earth than on any other planet. As a result, Martian days experience similar variations, with the Sun rising sooner and setting later in the summer and then experiencing the reverse in the winter.

However, seasonal variations last twice as long on Mars, thanks to Mars’ being at a greater distance from the Sun. This leads to the Martian year being about two Earth years long – 686.971 Earth days to be exact, which works out to 668.5991 Martian days (or Sols). As a result, longer days and longer nights can be expected last much longer on the Red Planet. Something for future colonists to consider!

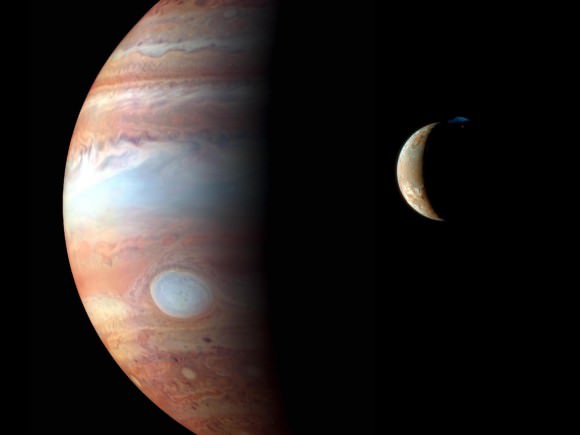

A Day On Jupiter:

Given the fact that it is the largest planet in the Solar System, one would expect that a day on Jupiter would last a long time. But as it turns out, a Jovian day is officially only 9 hours, 55 minutes and 30 seconds long, which means a single day is just over a third the length of an Earth day. This is due to the gas giant having a very rapid rotational speed, which is 12.6 km/s (45,300 km/h, or 28148.115 mph) at the equator. This rapid rotational speed is also one of the reasons the planet has such violent storms.

Note the use of the word officially. Since Jupiter is not a solid body, its upper atmosphere undergoes a different rate of rotation compared to its equator. Basically, the rotation of Jupiter’s polar atmosphere is about 5 minutes longer than that of the equatorial atmosphere. Because of this, astronomers use three systems as frames of reference.

System I applies from the latitudes 10° N to 10° S, where its rotational period is the planet’s shortest, at 9 hours, 50 minutes, and 30 seconds. System II applies at all latitudes north and south of these; its period is 9 hours, 55 minutes, and 40.6 seconds. System III corresponds to the rotation of the planet’s magnetosphere, and it’s period is used by the IAU and IAG to define Jupiter’s official rotation (i.e. 9 hours 44 minutes and 30 seconds)

So if you could, theoretically, stand on the cloud tops of Jupiter (or possibly on a floating platform in geosynchronous orbit), you would witness the sun rising an setting in the space of less than 10 hours from any latitude. And in the space of a single Jovian year, the sun would rise and set a total of about 10,476 times.

A Day On Saturn:

Saturn’s situation is very similar to that of Jupiter’s. Despite its massive size, the planet has an estimated rotational velocity of 9.87 km/s (35,500 km/h, or 22058.677 mph). As such Saturn takes about 10 hours and 33 minutes to complete a single sidereal rotation, making a single day on Saturn less than half of what it is here on Earth. Here too, this rapid movement of the atmosphere leads to some super storms, not to mention the hexagonal pattern around the planet’s north pole and a vortex storm around its south pole.

And, also like Jupiter, Saturn takes its time orbiting the Sun. With an orbital period that is the equivalent of 10,759.22 Earth days (or 29.4571 Earth years), a single Saturnian (or Cronian) year lasts roughly 24,491 Saturnian days. However, like Jupiter, Saturn’s atmosphere rotates at different speed depending on latitude, which requires that astronomers use three systems with different frames of reference.

System I encompasses the Equatorial Zone, the South Equatorial Belt and the North Equatorial Belt, and has a period of 10 hours and 14 minutes. System II covers all other Saturnian latitudes, excluding the north and south poles, and have been assigned a rotation period of 10 hr 38 min 25.4 sec. System III uses radio emissions to measure Saturn’s internal rotation rate, which yielded a rotation period of 10 hr 39 min 22.4 sec.

Using these various systems, scientists have obtained different data from Saturn over the years. For instance, data obtained during the 1980’s by the Voyager 1 and 2 missions indicated that a day on Saturn was 10 hours 39 minutes and 24 seconds long. In 2004, data provided by the Cassini-Huygens space probe measured the planet’s gravitational field, which yielded an estimate of 10 hours, 45 minutes, and 45 seconds (± 36 sec).

In 2007, this was revised by researches at the Department of Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences, UCLA, which resulted in the current estimate of 10 hours and 33 minutes. Much like with Jupiter, the problem of obtaining accurate measurements arises from the fact that, as a gas giant, parts of Saturn rotate faster than others.

A Day On Uranus:

When we come to Uranus, the question of how long a day is becomes a bit complicated. One the one hand, the planet has a sidereal rotation period of 17 hours 14 minutes and 24 seconds, which is the equivalent of 0.71833 Earth days. So you could say a day on Uranus lasts almost as long as a day on Earth. It would be true, were it not for the extreme axial tilt this gas/ice giant has going on.

With an axial tilt of 97.77°, Uranus essentially orbits the Sun on its side. This means that either its north or south pole is pointed almost directly at the Sun at different times in its orbital period. When one pole is going through “summer” on Uranus, it will experience 42 years of continuous sunlight. When that same pole is pointed away from the Sun (i.e. a Uranian “winter”), it will experience 42 years of continuous darkness.

Hence, you might say that a single day – from one sunrise to the next – lasts a full 84 years on Uranus! In other words, a single Uranian day is the same amount of time as a single Uranian year (84.0205 Earth years).

In addition, as with the other gas/ice giants, Uranus rotates faster at certain latitudes. Ergo, while the planet’s rotation is 17 hours and 14.5 minutes at the equator, at about 60° south, visible features of the atmosphere move much faster, making a full rotation in as little as 14 hours.

A Day On Neptune:

Last, but not least, we have Neptune. Here too, measuring a single day is somewhat complicated. For instance, Neptune’s sidereal rotation period is roughly 16 hours, 6 minutes and 36 seconds (the equivalent of 0.6713 Earth days). But due to it being a gas/ice giant, the poles of the planet rotate faster than the equator.

Whereas the planet’s magnetic field has a rotational speed of 16.1 hours, the wide equatorial zone rotates with a period of about 18 hour. Meanwhile, the polar regions rotate the fastest, at a period of 12 hours. This differential rotation is the most pronounced of any planet in the Solar System, and it results in strong latitudinal wind shear.

In addition, the planet’s axial tilt of 28.32° results in seasonal variations that are similar to those on Earth and Mars. The long orbital period of Neptune means that the seasons last for forty Earth years. But because its axial tilt is comparable to Earth’s, the variation in the length of its day over the course of its long year is not any more extreme.

As you can see from this little rundown of the different planets in our Solar System, what constitutes a day depends entirely on your frame of reference. In addition to it varying depending on the planet in question, you also have to take into account seasonal cycles and where on the planet the measurements are being taken from.

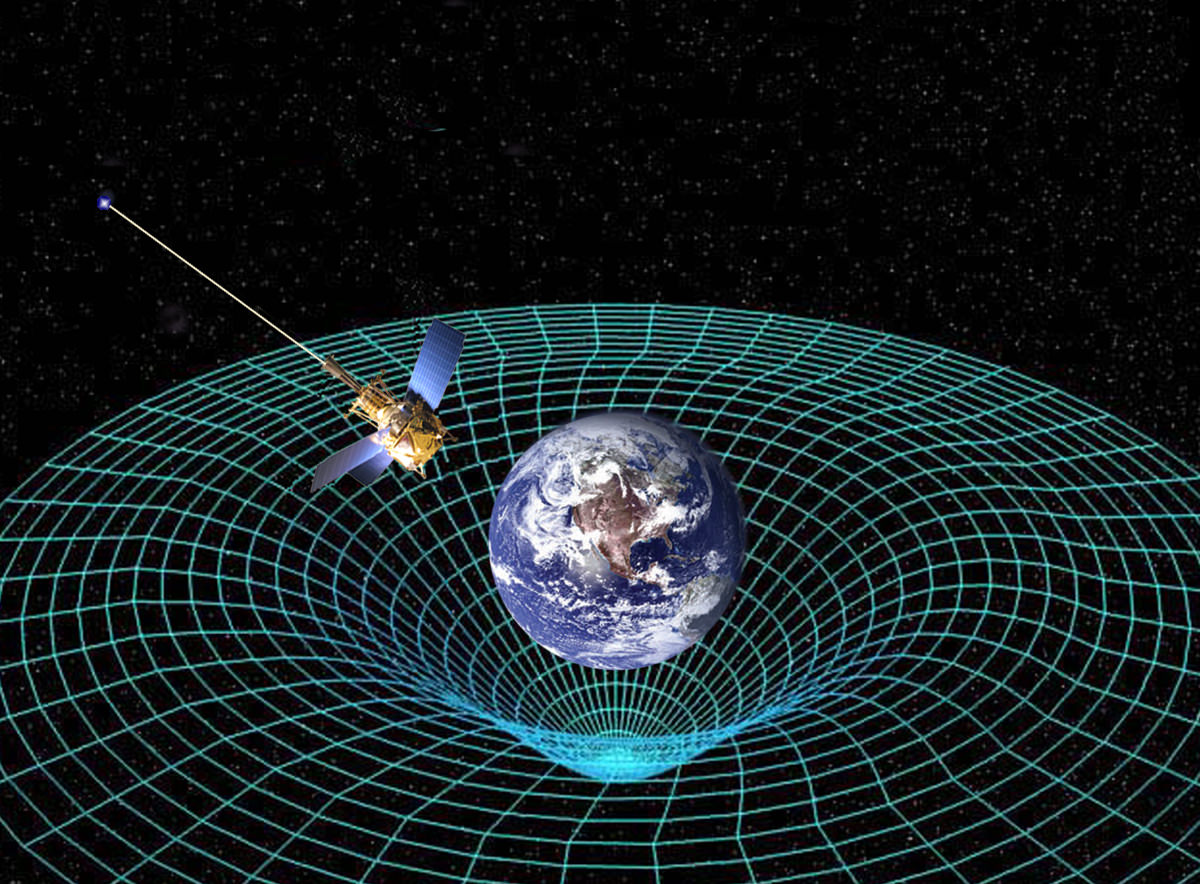

As Einstein summarized, time is relative to the observer. Based on your inertial reference frame, its passage will differ. And when you are standing on a planet other than Earth, your concept of day and night, which is set to Earth time (and a specific time zone) is likely to get pretty confused!

We have written many interesting articles about how time is measured on other planets here at Universe Today. For example, here’s How Long Is A Year On The Other Planets?, Which Planet Has the Longest Day?, The Rotation of Venus, How Long Is A Day on Mars? and How Long Is A Day On Jupiter?.

If you are looking for more information, check out Our Solar System at Space.com

Astronomy Cast has episodes on all the planets, including Episode 49: Mercury, and Episode 95: Humans to Mars, Part 2 – Colonists

First Space Zinnia Blooms and Catches Sun’s Rays on Space Station

The first Zinnia flower to bloom in space is dramatically catching the sun’s rays like we have never seen before – through the windows of the Cupola on the International Space Station (ISS) while simultaneously providing a splash of soothing color, nature and reminders of home to the multinational crew living and working on the orbital science laboratory.

Furthermore its contributing invaluable experience to scientists and astronauts on learning how to grow plants and food in microgravity during future deep space human expeditions planned for NASA’s “Journey to Mars” initiative.

NASA astronaut and Expedition 46 Commander Scott Kelly is proudly sharing stunning new photos showing off his space grown Zinnias – which bloomed for the first time on Jan. 16, all thanks to his experienced green thumb. Continue reading “First Space Zinnia Blooms and Catches Sun’s Rays on Space Station”

Space Zinnias Rebound from Space Blight on Space Station

Zinnia experimental plants growing aboard the International Space Station (ISS) have staged a dramatic New Year’s comeback from a potential near death experience over the Christmas holidays, when traces of mold were discovered.

And it’s all thanks to the experienced green thumb of Space Station Commander Scott Kelly, channeling his “inner Mark Watney!” Continue reading “Space Zinnias Rebound from Space Blight on Space Station”

What Is The Atmosphere Like On Other Planets?

Here on Earth, we tend to take our atmosphere for granted, and not without reason. Our atmosphere has a lovely mix of nitrogen and oxygen (78% and 21% respectively) with trace amounts of water vapor, carbon dioxide and other gaseous molecules. What’s more, we enjoy an atmospheric pressure of 101.325 kPa, which extends to an altitude of about 8.5 km.

In short, our atmosphere is plentiful and life-sustaining. But what about the other planets of the Solar System? How do they stack up in terms of atmospheric composition and pressure? We know for a fact that they are not breathable by humans and cannot support life. But just what is the difference between these balls of rock and gas and our own?

For starters, it should be noted that every planet in the Solar System has an atmosphere of one kind or another. And these range from incredibly thin and tenuous (such as Mercury’s “exosphere”) to the incredibly dense and powerful – which is the case for all of the gas giants. And depending on the composition of the planet, whether it is a terrestrial or a gas/ice giant, the gases that make up its atmosphere range from either the hydrogen and helium to more complex elements like oxygen, carbon dioxide, ammonia and methane.

Mercury’s Atmosphere:

Mercury is too hot and too small to retain an atmosphere. However, it does have a tenuous and variable exosphere that is made up of hydrogen, helium, oxygen, sodium, calcium, potassium and water vapor, with a combined pressure level of about 10-14 bar (one-quadrillionth of Earth’s atmospheric pressure). It is believed this exosphere was formed from particles captured from the Sun, volcanic outgassing and debris kicked into orbit by micrometeorite impacts.

Because it lacks a viable atmosphere, Mercury has no way to retain the heat from the Sun. As a result of this and its high eccentricity, the planet experiences considerable variations in temperature. Whereas the side that faces the Sun can reach temperatures of up to 700 K (427° C), while the side in shadow dips down to 100 K (-173° C).

Venus’ Atmosphere:

Surface observations of Venus have been difficult in the past, due to its extremely dense atmosphere, which is composed primarily of carbon dioxide with a small amount of nitrogen. At 92 bar (9.2 MPa), the atmospheric mass is 93 times that of Earth’s atmosphere and the pressure at the planet’s surface is about 92 times that at Earth’s surface.

Venus is also the hottest planet in our Solar System, with a mean surface temperature of 735 K (462 °C/863.6 °F). This is due to the CO²-rich atmosphere which, along with thick clouds of sulfur dioxide, generates the strongest greenhouse effect in the Solar System. Above the dense CO² layer, thick clouds consisting mainly of sulfur dioxide and sulfuric acid droplets scatter about 90% of the sunlight back into space.

Another common phenomena is Venus’ strong winds, which reach speeds of up to 85 m/s (300 km/h; 186.4 mph) at the cloud tops and circle the planet every four to five Earth days. At this speed, these winds move up to 60 times the speed of the planet’s rotation, whereas Earth’s fastest winds are only 10-20% of the planet’s rotational speed.

Venus flybys have also indicated that its dense clouds are capable of producing lightning, much like the clouds on Earth. Their intermittent appearance indicates a pattern associated with weather activity, and the lightning rate is at least half of that on Earth.

Earth’s Atmosphere:

Earth’s atmosphere, which is composed of nitrogen, oxygen, water vapor, carbon dioxide and other trace gases, also consists of five layers. These consists of the Troposphere, the Stratosphere, the Mesosphere, the Thermosphere, and the Exosphere. As a rule, air pressure and density decrease the higher one goes into the atmosphere and the farther one is from the surface.

Closest to the Earth is the Troposphere, which extends from the 0 to between 12 km and 17 km (0 to 7 and 10.56 mi) above the surface. This layer contains roughly 80% of the mass of Earth’s atmosphere, and nearly all atmospheric water vapor or moisture is found in here as well. As a result, it is the layer where most of Earth’s weather takes place.

The Stratosphere extends from the Troposphere to an altitude of 50 km (31 mi). This layer extends from the top of the troposphere to the stratopause, which is at an altitude of about 50 to 55 km (31 to 34 mi). This layer of the atmosphere is home to the ozone layer, which is the part of Earth’s atmosphere that contains relatively high concentrations of ozone gas.

![Space Shuttle Endeavour sillouetted against the atmosphere. The orange layer is the troposphere, the white layer is the stratosphere and the blue layer the mesosphere.[1] (The shuttle is actually orbiting at an altitude of more than 320 km (200 mi), far above all three layers.) Credit: NASA](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/Endeavour_silhouette_STS-130-580x387.jpg)

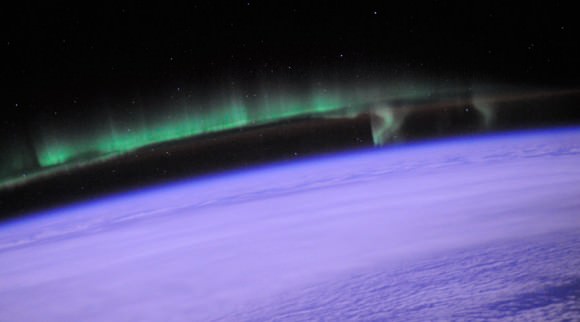

The lower part of the thermosphere, from 80 to 550 kilometers (50 to 342 mi), contains the ionosphere – which is so named because it is here in the atmosphere that particles are ionized by solar radiation. This layer is completely cloudless and free of water vapor. It is also at this altitude that the phenomena known as Aurora Borealis and Aurara Australis are known to take place.

The Exosphere, which is outermost layer of the Earth’s atmosphere, extends from the exobase – located at the top of the thermosphere at an altitude of about 700 km above sea level – to about 10,000 km (6,200 mi). The exosphere merges with the emptiness of outer space, and is mainly composed of extremely low densities of hydrogen, helium and several heavier molecules including nitrogen, oxygen and carbon dioxide

The exosphere is located too far above Earth for any meteorological phenomena to be possible. However, the Aurora Borealis and Aurora Australis sometimes occur in the lower part of the exosphere, where they overlap into the thermosphere.

The average surface temperature on Earth is approximately 14°C; but as already noted, this varies. For instance, the hottest temperature ever recorded on Earth was 70.7°C (159°F), which was taken in the Lut Desert of Iran. Meanwhile, the coldest temperature ever recorded on Earth was measured at the Soviet Vostok Station on the Antarctic Plateau, reaching an historic low of -89.2°C (-129°F).

Mars’ Atmosphere:

Planet Mars has a very thin atmosphere which is composed of 96% carbon dioxide, 1.93% argon and 1.89% nitrogen along with traces of oxygen and water. The atmosphere is quite dusty, containing particulates that measure 1.5 micrometers in diameter, which is what gives the Martian sky a tawny color when seen from the surface. Mars’ atmospheric pressure ranges from 0.4 – 0.87 kPa, which is equivalent to about 1% of Earth’s at sea level.

Because of its thin atmosphere, and its greater distance from the Sun, the surface temperature of Mars is much colder than what we experience here on Earth. The planet’s average temperature is -46 °C (51 °F), with a low of -143 °C (-225.4 °F) during the winter at the poles, and a high of 35 °C (95 °F) during summer and midday at the equator.

The planet also experiences dust storms, which can turn into what resembles small tornadoes. Larger dust storms occur when the dust is blown into the atmosphere and heats up from the Sun. The warmer dust filled air rises and the winds get stronger, creating storms that can measure up to thousands of kilometers in width and last for months at a time. When they get this large, they can actually block most of the surface from view.

Trace amounts of methane have also been detected in the Martian atmosphere, with an estimated concentration of about 30 parts per billion (ppb). It occurs in extended plumes, and the profiles imply that the methane was released from specific regions – the first of which is located between Isidis and Utopia Planitia (30°N 260°W) and the second in Arabia Terra (0°N 310°W).

Ammonia was also tentatively detected on Mars by the Mars Express satellite, but with a relatively short lifetime. It is not clear what produced it, but volcanic activity has been suggested as a possible source.

Jupiter’s Atmosphere:

Much like Earth, Jupiter experiences auroras near its northern and southern poles. But on Jupiter, the auroral activity is much more intense and rarely ever stops. The intense radiation, Jupiter’s magnetic field, and the abundance of material from Io’s volcanoes that react with Jupiter’s ionosphere create a light show that is truly spectacular.

Jupiter also experiences violent weather patterns. Wind speeds of 100 m/s (360 km/h) are common in zonal jets, and can reach as high as 620 kph (385 mph). Storms form within hours and can become thousands of km in diameter overnight. One storm, the Great Red Spot, has been raging since at least the late 1600s. The storm has been shrinking and expanding throughout its history; but in 2012, it was suggested that the Giant Red Spot might eventually disappear.

Jupiter is perpetually covered with clouds composed of ammonia crystals and possibly ammonium hydrosulfide. These clouds are located in the tropopause and are arranged into bands of different latitudes, known as “tropical regions”. The cloud layer is only about 50 km (31 mi) deep, and consists of at least two decks of clouds: a thick lower deck and a thin clearer region.

There may also be a thin layer of water clouds underlying the ammonia layer, as evidenced by flashes of lightning detected in the atmosphere of Jupiter, which would be caused by the water’s polarity creating the charge separation needed for lightning. Observations of these electrical discharges indicate that they can be up to a thousand times as powerful as those observed here on the Earth.

Saturn’s Atmosphere:

The outer atmosphere of Saturn contains 96.3% molecular hydrogen and 3.25% helium by volume. The gas giant is also known to contain heavier elements, though the proportions of these relative to hydrogen and helium is not known. It is assumed that they would match the primordial abundance from the formation of the Solar System.

Trace amounts of ammonia, acetylene, ethane, propane, phosphine and methane have been also detected in Saturn’s atmosphere. The upper clouds are composed of ammonia crystals, while the lower level clouds appear to consist of either ammonium hydrosulfide (NH4SH) or water. Ultraviolet radiation from the Sun causes methane photolysis in the upper atmosphere, leading to a series of hydrocarbon chemical reactions with the resulting products being carried downward by eddies and diffusion.

Saturn’s atmosphere exhibits a banded pattern similar to Jupiter’s, but Saturn’s bands are much fainter and wider near the equator. As with Jupiter’s cloud layers, they are divided into the upper and lower layers, which vary in composition based on depth and pressure. In the upper cloud layers, with temperatures in range of 100–160 K and pressures between 0.5–2 bar, the clouds consist of ammonia ice.

Water ice clouds begin at a level where the pressure is about 2.5 bar and extend down to 9.5 bar, where temperatures range from 185–270 K. Intermixed in this layer is a band of ammonium hydrosulfide ice, lying in the pressure range 3–6 bar with temperatures of 290–235 K. Finally, the lower layers, where pressures are between 10–20 bar and temperatures are 270–330 K, contains a region of water droplets with ammonia in an aqueous solution.

On occasion, Saturn’s atmosphere exhibits long-lived ovals, similar to what is commonly observed on Jupiter. Whereas Jupiter has the Great Red Spot, Saturn periodically has what’s known as the Great White Spot (aka. Great White Oval). This unique but short-lived phenomenon occurs once every Saturnian year, roughly every 30 Earth years, around the time of the northern hemisphere’s summer solstice.

These spots can be several thousands of kilometers wide, and have been observed in 1876, 1903, 1933, 1960, and 1990. Since 2010, a large band of white clouds called the Northern Electrostatic Disturbance have been observed enveloping Saturn, which was spotted by the Cassini space probe. If the periodic nature of these storms is maintained, another one will occur in about 2020.

The winds on Saturn are the second fastest among the Solar System’s planets, after Neptune’s. Voyager data indicate peak easterly winds of 500 m/s (1800 km/h). Saturn’s northern and southern poles have also shown evidence of stormy weather. At the north pole, this takes the form of a hexagonal wave pattern, whereas the south shows evidence of a massive jet stream.

The persisting hexagonal wave pattern around the north pole was first noted in the Voyager images. The sides of the hexagon are each about 13,800 km (8,600 mi) long (which is longer than the diameter of the Earth) and the structure rotates with a period of 10h 39m 24s, which is assumed to be equal to the period of rotation of Saturn’s interior.

The south pole vortex, meanwhile, was first observed using the Hubble Space Telescope. These images indicated the presence of a jet stream, but not a hexagonal standing wave. These storms are estimated to be generating winds of 550 km/h, are comparable in size to Earth, and believed to have been going on for billions of years. In 2006, the Cassini space probe observed a hurricane-like storm that had a clearly defined eye. Such storms had not been observed on any planet other than Earth – even on Jupiter.

Uranus’ Atmosphere:

As with Earth, the atmosphere of Uranus is broken into layers, depending upon temperature and pressure. Like the other gas giants, the planet doesn’t have a firm surface, and scientists define the surface as the region where the atmospheric pressure exceeds one bar (the pressure found on Earth at sea level). Anything accessible to remote-sensing capability – which extends down to roughly 300 km below the 1 bar level – is also considered to be the atmosphere.

Using these references points, Uranus’ atmosphere can be divided into three layers. The first is the troposphere, between altitudes of -300 km below the surface and 50 km above it, where pressures range from 100 to 0.1 bar (10 MPa to 10 kPa). The second layer is the stratosphere, which reaches between 50 and 4000 km and experiences pressures between 0.1 and 10-10 bar (10 kPa to 10 µPa).

The troposphere is the densest layer in Uranus’ atmosphere. Here, the temperature ranges from 320 K (46.85 °C/116 °F) at the base (-300 km) to 53 K (-220 °C/-364 °F) at 50 km, with the upper region being the coldest in the solar system. The tropopause region is responsible for the vast majority of Uranus’s thermal infrared emissions, thus determining its effective temperature of 59.1 ± 0.3 K.

Within the troposphere are layers of clouds – water clouds at the lowest pressures, with ammonium hydrosulfide clouds above them. Ammonia and hydrogen sulfide clouds come next. Finally, thin methane clouds lay on the top.

In the stratosphere, temperatures range from 53 K (-220 °C/-364 °F) at the upper level to between 800 and 850 K (527 – 577 °C/980 – 1070 °F) at the base of the thermosphere, thanks largely to heating caused by solar radiation. The stratosphere contains ethane smog, which may contribute to the planet’s dull appearance. Acetylene and methane are also present, and these hazes help warm the stratosphere.

The outermost layer, the thermosphere and corona, extend from 4,000 km to as high as 50,000 km from the surface. This region has a uniform temperature of 800-850 (577 °C/1,070 °F), although scientists are unsure as to the reason. Because the distance to Uranus from the Sun is so great, the amount of sunlight absorbed cannot be the primary cause.

Like Jupiter and Saturn, Uranus’s weather follows a similar pattern where systems are broken up into bands that rotate around the planet, which are driven by internal heat rising to the upper atmosphere. As a result, winds on Uranus can reach up to 900 km/h (560 mph), creating massive storms like the one spotted by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2012. Similar to Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, this “Dark Spot” was a giant cloud vortex that measured 1,700 kilometers by 3,000 kilometers (1,100 miles by 1,900 miles).

Neptune’s Atmosphere:

At high altitudes, Neptune’s atmosphere is 80% hydrogen and 19% helium, with a trace amount of methane. As with Uranus, this absorption of red light by the atmospheric methane is part of what gives Neptune its blue hue, although Neptune’s is darker and more vivid. Because Neptune’s atmospheric methane content is similar to that of Uranus, some unknown constituent is thought to contribute to Neptune’s more intense coloring.

Neptune’s atmosphere is subdivided into two main regions: the lower troposphere (where temperature decreases with altitude), and the stratosphere (where temperature increases with altitude). The boundary between the two, the tropopause, lies at a pressure of 0.1 bars (10 kPa). The stratosphere then gives way to the thermosphere at a pressure lower than 10-5 to 10-4 microbars (1 to 10 Pa), which gradually transitions to the exosphere.

Neptune’s spectra suggest that its lower stratosphere is hazy due to condensation of products caused by the interaction of ultraviolet radiation and methane (i.e. photolysis), which produces compounds such as ethane and ethyne. The stratosphere is also home to trace amounts of carbon monoxide and hydrogen cyanide, which are responsible for Neptune’s stratosphere being warmer than that of Uranus.

For reasons that remain obscure, the planet’s thermosphere experiences unusually high temperatures of about 750 K (476.85 °C/890 °F). The planet is too far from the Sun for this heat to be generated by ultraviolet radiation, which means another heating mechanism is involved – which could be the atmosphere’s interaction with ion’s in the planet’s magnetic field, or gravity waves from the planet’s interior that dissipate in the atmosphere.

Because Neptune is not a solid body, its atmosphere undergoes differential rotation. The wide equatorial zone rotates with a period of about 18 hours, which is slower than the 16.1-hour rotation of the planet’s magnetic field. By contrast, the reverse is true for the polar regions where the rotation period is 12 hours.

This differential rotation is the most pronounced of any planet in the Solar System, and results in strong latitudinal wind shear and violent storms. The three most impressive were all spotted in 1989 by the Voyager 2 space probe, and then named based on their appearances.

The first to be spotted was a massive anticyclonic storm measuring 13,000 x 6,600 km and resembling the Great Red Spot of Jupiter. Known as the Great Dark Spot, this storm was not spotted five later (Nov. 2nd, 1994) when the Hubble Space Telescope looked for it. Instead, a new storm that was very similar in appearance was found in the planet’s northern hemisphere, suggesting that these storms have a shorter life span than Jupiter’s.

The Scooter is another storm, a white cloud group located farther south than the Great Dark Spot – a nickname that first arose during the months leading up to the Voyager 2 encounter in 1989. The Small Dark Spot, a southern cyclonic storm, was the second-most-intense storm observed during the 1989 encounter. It was initially completely dark; but as Voyager 2 approached the planet, a bright core developed and could be seen in most of the highest-resolution images.

In sum, the planet’s of our Solar System all have atmospheres of sorts. And compared to Earth’s relatively balmy and thick atmosphere, they run the gamut between very very thin to very very dense. They also range in temperatures from the extremely hot (like on Venus) to the extreme freezing cold.

And when it comes to weather systems, things can equally extreme, with planet’s boasting either weather at all, or intense cyclonic and dust storms that put storms here n Earth to shame. And whereas some are entirely hostile to life as we know it, others we might be able to work with.

We have many interesting articles about planetary atmosphere’s here at Universe Today. For instance, he’s What is the Atmosphere?, and articles about the atmosphere of Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune,

For more information on atmospheres, check out NASA’s pages on Earth’s Atmospheric Layers, The Carbon Cycle, and how Earth’s atmosphere differs from space.

Astronomy Cast has an episode on the source of the atmosphere.

Spirit Rover Touchdown 12 Years Ago Started Spectacular Martian Science Adventure

Exactly 12 Years ago this week, NASA’s now famous Spirit rover touched down on the Red Planet, starting a spectacular years long campaign of then unimaginable science adventures that ended up revolutionizing our understanding of Mars due to her totally unexpected longevity.

For although she was only “warrantied” to function a mere 90 Martian days, or sols, the six wheeled emissary from Earth survived more than six years – and was thus transformed into the world renowned robot still endearing to humanity today. Continue reading “Spirit Rover Touchdown 12 Years Ago Started Spectacular Martian Science Adventure”

Will 2016 Be the Year Elon Musk Reveals his Mars Colonial Transporter Plans?

There are several space stories we’re anticipating for 2016 but one story might appear — to some — to belong in the realm of science fiction: sometime in the coming year Elon Musk will likely reveal his plans for colonizing Mars.

Early in 2015, Musk hinted that he would be publicly disclosing his strategies for the Mars Colonial Transport system sometime in late 2015, but then later said the announcement would come in 2016.

“The Mars transport system will be a completely new architecture,” Musk said during a Reddit AMA in January 2015, replying to a question about the development of MCT. “[I] am hoping to present that towards the end of this year. Good thing we didn’t do it sooner, as we have learned a huge amount from Falcon and Dragon.”

Big Rockets

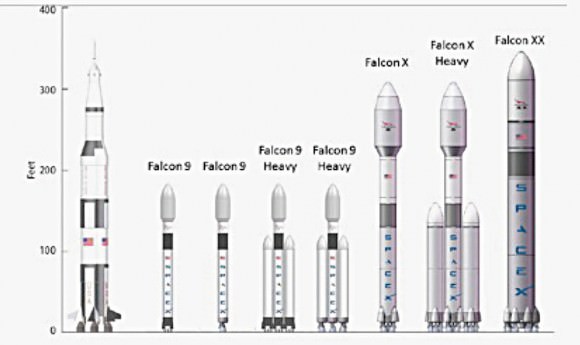

As far as any details, Musk only said that he wants to be able to send 100 colonists to Mars at a time, and the “goal is 100 metric tons of useful payload to the surface of Mars. This obviously requires a very big spaceship and booster system.”

He has supposedly dubbed the rocket the BFR (for Big F’n Rocket) and the spaceship similarly as BFS.

And he wants it to be reusable, which Musk and SpaceX have said is the key to making human life multiplanetary. The recent successful return and vertical landing of the Falcon 9’s first stage makes that closer to reality than ever.

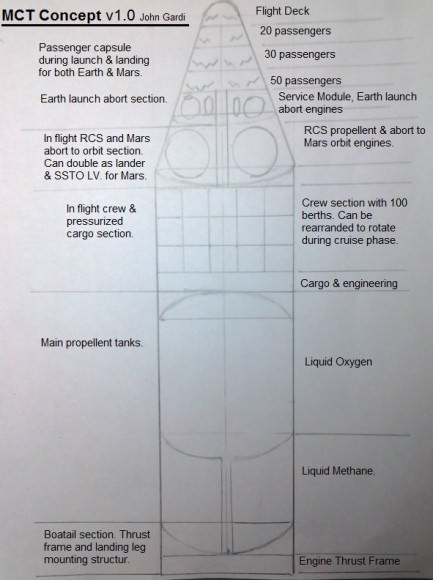

While SpaceX has no publicly shared concept illustrations as of yet, a few enthusiasts on the web have shared their visions of MCT, such as this discussion on Reddit , and the drawing below by engineer John Gardi, who recently proposed his ideas for the MCT on Reddit.

Most online discussions describe the MCT as an interplanetary ferry, with the spaceship built on the ground and launched into orbit in one piece and perhaps refueled in low Earth orbit. The transporter could be powered by Raptor engines, which are cryogenic methane-fueled rocket engines rumored to be under development by SpaceX.

The Challenge of Landing Large Payloads on Mars

While the big rocket and spaceship may seem to be a big hurdle, an even larger challenge is how to land a payload of 100 metric tons with 100 colonists, as Musk proposes, on Mars surface.

As we’ve discussed previously, there is a “Supersonic Transition Problem” at Mars. Mars’ thin atmosphere does not provide an enough aerodynamics to land a large vehicle like we can on Earth, but it is thick enough that thrusters such as what was used by the Apollo landers can’t be used without encountering aerodynamic problems such as sheering and incredible stress on the vehicle.

“Unique to Mars, there is a velocity-altitude gap below Mach 5,” explained Rob Manning from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in our article from 2007. “The gap is between the delivery capability of large entry systems at Mars and the capability of super-and sub-sonic decelerator technologies to get below the speed of sound.”

With current landing technology, a large, heavy human-sized vehicle streaking through Mars’ thin, volatile atmosphere only has about 90 seconds to slow from Mach 5 to under Mach 1, change and re-orient itself from a being a spacecraft to a lander, deploy parachutes to slow down further, then use thrusters to translate to the landing site and gently touch down.

90 seconds is not enough time, and the airbags used for rovers like Spirit and Opportunity and even the Skycrane system used for the Curiosity rover can’t be scaled up enough to land the size of payloads needed for humans on Mars.

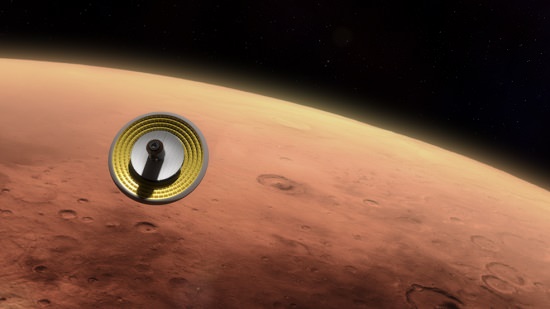

NASA has been addressing this problem to a small degree, and has tested out inflatable aeroshells that can provide enough aerodynamic drag to decelerate and deliver larger payloads. Called Hypersonic Inflatable Aerodynamic Decelerator (HIAD), this is the best hope on the horizon for landing large payloads on Mars.

The Inflatable Reentry Vehicle Experiment (IRVE-3) was tested successfully in 2012. It was made of high tech fabric and inflated to create the shape and structure similar to a mushroom. When inflated, the IRVE-3 is about 10-ft (3 meter) in diameter, and is composed of a seven giant braided Kevlar rings stacked and lashed together – then covered by a thermal blanket made up of layers of heat resistant materials. These kinds of aeroshells can also generate lift, which would allow for additional slowing of the vehicle.

“NASA is currently developing and flight testing HIADs — a new class of relatively lightweight deployable aeroshells that could safely deliver more than 22 tons to the surface of Mars,” said Steve Gaddis, GCD manager at NASA’s Langley Research Center in a press release from NASA in September 2015.

NASA is expecting that a crewed spacecraft landing on Mars would weigh between 15 and 30 tons, and the space agency is looking for ideas through its Big Idea Challenge for how to create aeroshells big enough to do the job.

With current technology, landing the 100 metric tons that Musk envisions might be out of reach. But if there’s someone who could figure it out and get it done, Elon Musk just might be that person.

Additional reading: Alan Boyle on Geekwire, GQ interview of Elon Musk.

How Strong is Gravity on Other Planets?

Gravity is a fundamental force of physics, one which we Earthlings tend to take for granted. You can’t really blame us. Having evolved over the course of billions of years in Earth’s environment, we are used to living with the pull of a steady 1 g (or 9.8 m/s²). However, for those who have gone into space or set foot on the Moon, gravity is a very tenuous and precious thing.

Basically, gravity is dependent on mass, where all things – from stars, planets, and galaxies to light and sub-atomic particles – are attracted to one another. Depending on the size, mass and density of the object, the gravitational force it exerts varies. And when it comes to the planets of our Solar System, which vary in size and mass, the strength of gravity on their surfaces varies considerably.

‘A City on Mars’ is Elon Musk’s Ultimate Goal Enabled by Rocket Reuse Technology

Elon Musk’s dream and ultimate goal of establishing a permanent human presence on the Red Planet in the form of “A City on Mars” took a gigantic step forward with the game changing rocket landing and recovery technology vividly demonstrated by his firm’s Falcon 9 booster this past Monday, Dec. 21 – following a successful blastoff from the Florida space coast just minutes earlier on the first SpaceX launch since a catastrophic mid-air calamity six months ago.

“I think this was a critical step along the way towards being able to establish a city on Mars,” said SpaceX billionaire founder and CEO Elon Musk at a media telecon shortly after Monday night’s (Dec. 21) launch and upright landing of the Falcon 9 rockets first stage on Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Fla. Continue reading “‘A City on Mars’ is Elon Musk’s Ultimate Goal Enabled by Rocket Reuse Technology”