Host: Fraser Cain (@fcain)

Special Guest: Amy Shira Teitel (@astVintageSpace) discussing space history and her new book Breaking the Chains of Gravity

Guests:

Morgan Rehnberg (cosmicchatter.org / @MorganRehnberg )

This Week’s Stories:

Falcon 9 launch and (almost!) landing

NASA Invites ESA to Build Europa Piggyback Probe

Bouncing Philae Reveals Comet is Not Magnetised

Astronomers Watch Starbirth in Real Time

SpaceX Conducts Tanking Test on In-Flight Abort Falcon 9

Rosetta Team Completely Rethinking Comet Close Encounter Strategy

Apollo 13 Custom LEGO Minifigures Mark Mission’s 45th Anniversary

LEGO Launching Awesome Spaceport Shuttle Sets in August

New Horizons Closes in on Pluto

Work Platform to be Installed in the Vehicle Assembly Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

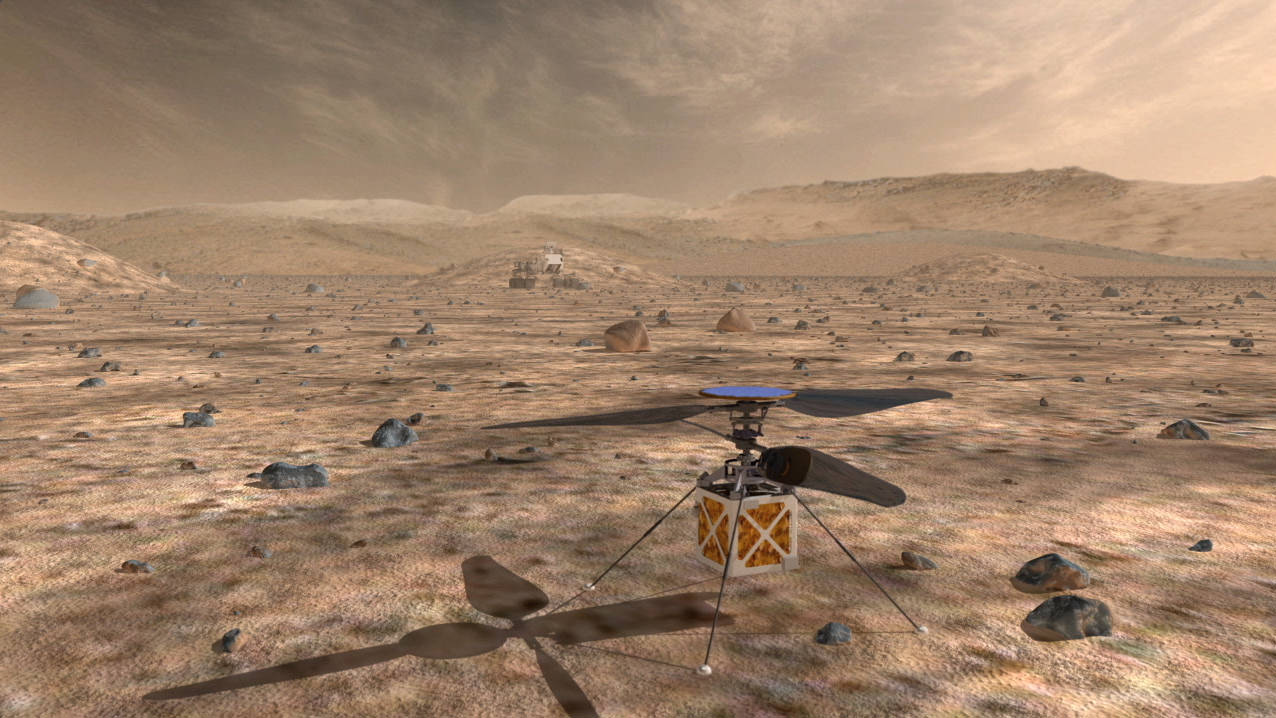

Watching the Sunsets of Mars Through Robot Eyes: Photos

NASA Invites ESA to Build Europa Piggyback Probe

ULA Plans to Introduce New Rocket One Piece at a Time

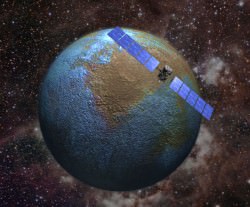

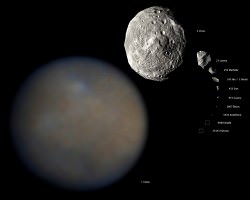

Two Mysterious Bright Spots on Dwarf Planet Ceres Are Not Alike

18 Image Montage Show Off Comet 67/P Activity

ULA’s Next Rocket To Be Named Vulcan

NASA Posts Huge Library of Space Sounds And You’re Free to Use Them

Explaining the Great 2011 Saturn Storm

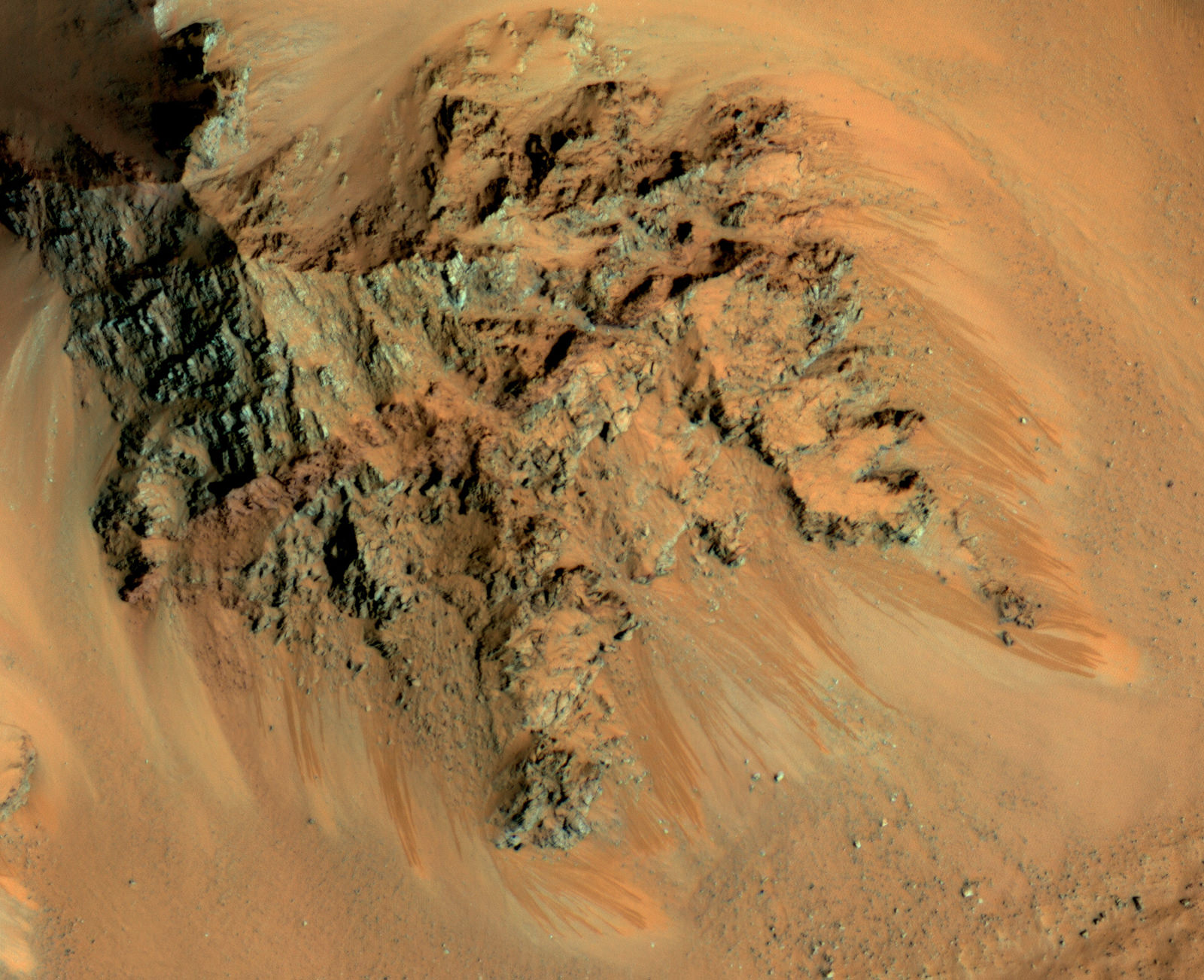

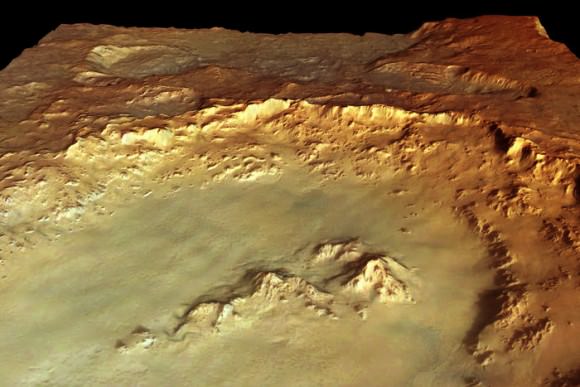

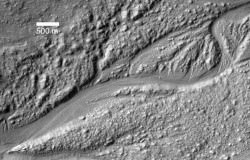

Liquid Salt Water May Exist on Mars

Color Map Suggests a Once-Active Ceres

Diverse Destinations Considered for New Interplanetary Probe

Paul Allen Asserts Rights to “Vulcan” Trademark, Challenging Name of New Rocket

First New Horizons Color Picture of Pluto and Charon

NASA’s Spitzer Spots Planet Deep Within Our Galaxy

Icy Tendrils Reaching into Saturn Ring Traced to Their Source

First Signs of Self-Interacting Dark Matter?

Anomaly Delays Launch of THOR 7 and SICRAL 2

Nearby Exoplanet’s Hellish Atmosphere Measured

The Universe Isn’t Accelerating As Fast As We Thought

Glitter Cloud May Serve As Space Mirror

Cassini Spots the Sombrero Galaxy from Saturn

EM-1 Orion Crew Module Set for First Weld Milestone in May

Special Delivery: NASA Marshall Receives 3D-Printed Tools from Space

The Roomba for Lawns is Really Pissing Off Astronomers

Giant Galaxies Die from the Inside Out

ALMA Reveals Intense Magnetic Field Close to Supermassive Black Hole

Dawn Glimpses Ceres’ North Pole

Lapcat A2 Concept Sup-Orbital Spaceplane SABRE Engine Passed Feasibility Test by USAF Research Lab

50 Years Since the First Full Saturn V Test Fire

ULA CEO Outlines BE-4 Engine Reuse Economic Case

Certification Process Begins for Vulcan to Carry Military Payloads

Major Advance in Artificial Photosynthesis Poses Win/Win for the Environment

45th Anniversary [TODAY] of Apollo 13’s Safe Return to Earth

Hubble’s Having A Party in Washington Next Week (25th Anniversary of Hubble)

Don’t forget, the Cosmoquest Hangoutathon is coming soon!

We record the Weekly Space Hangout every Friday at 12:00 pm Pacific / 3:00 pm Eastern. You can watch us live on Google+, Universe Today, or the Universe Today YouTube page.

You can join in the discussion between episodes over at our Weekly Space Hangout Crew group in G+, and suggest your ideas for stories we can discuss each week!