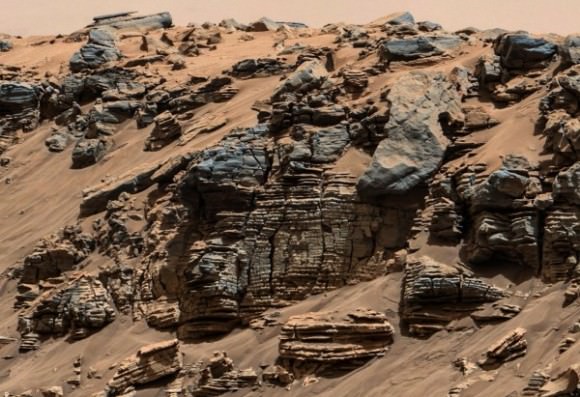

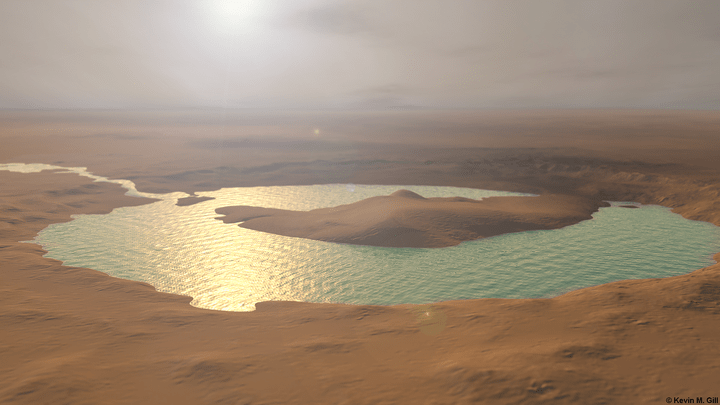

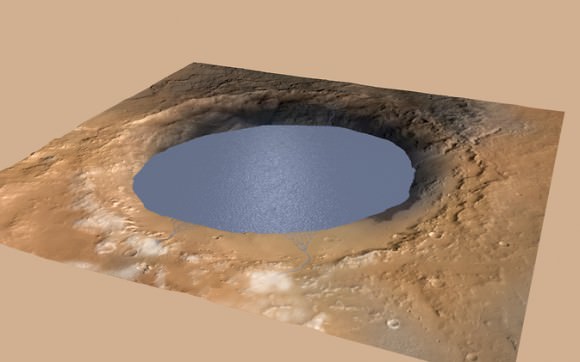

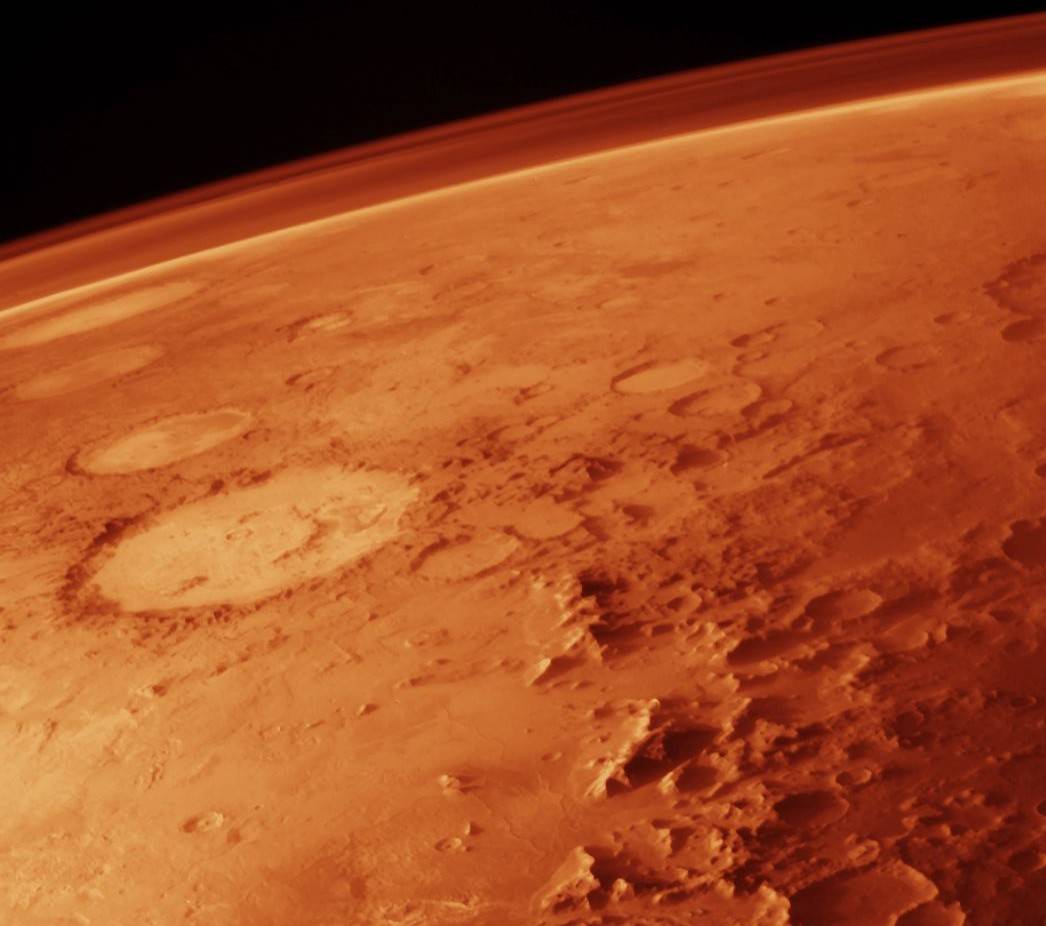

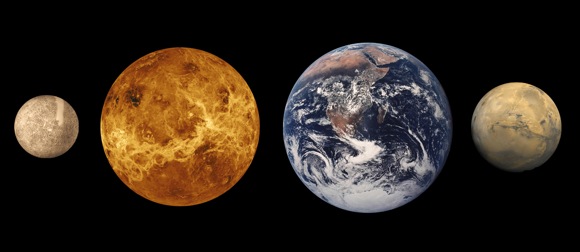

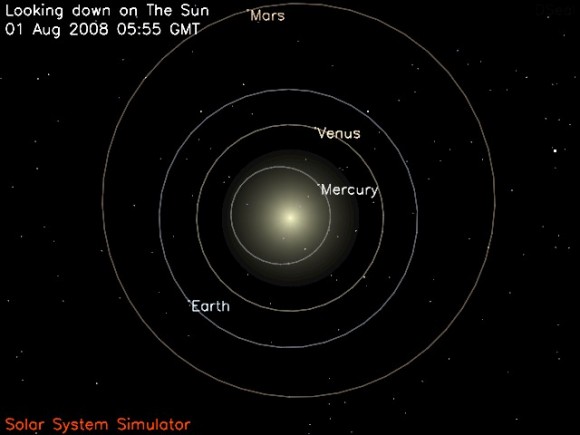

While scientists believe that at one time, billions of years ago, Mars had an atmosphere similar to Earth’s and was covered with flowing water, the reality today is quite different. In fact, the surface of Mars is so hostile that a vacation in Antarctica would seem pleasant by comparison.

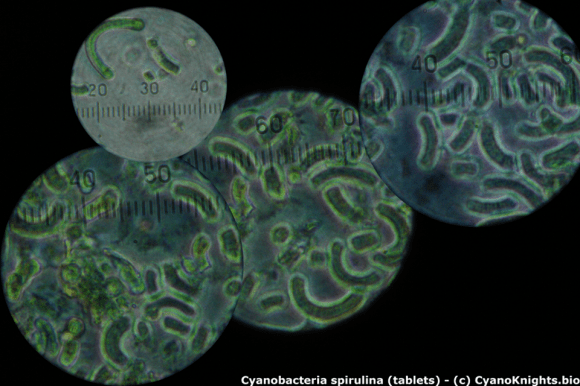

In addition to the extreme cold, there is little atmosphere to speak of and virtually no oxygen. However, a team of students from Germany wants to change that. Their plan is to introduce cyanobacteria into the atmosphere which would convert the ample supplies of CO² into oxygen gas, thus paving the way for possible settlement someday.

The team, which is composed of students and volunteer scientists from the University of Applied Science and the Technical University in Darmstadt, Germany, call their project “Cyano Knights”. Basically, they plan to seed Mars’ atmosphere with cyanobacteria so it can convert Mars’ most abundant gas (CO2, which accounts for 96% of the Martian atmosphere) into something breathable by humans.

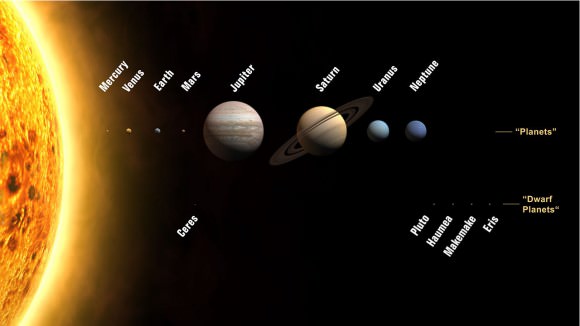

Along with teams from other universities and technical colleges taking part in the Mars One University Competition, the Cyano Knights hope that their project will be the one sent to the Red Planet in advance of the company’s proposed settlers.

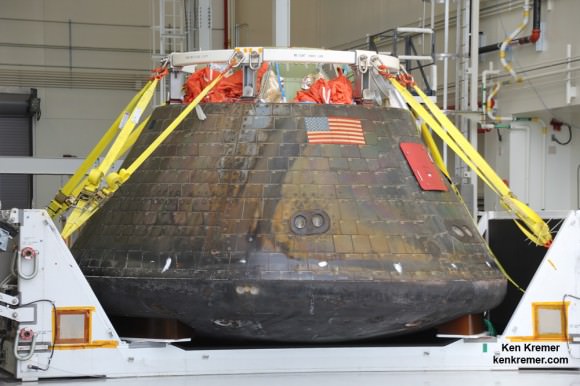

This competition officially began this past summer, as part of the Mars One’s drive to enlist the support and participation of universities from all around the world. All those participating will have a chance to send their project aboard the company’s first unmanned lander, which will be sent to Mars in 2018.

Working out of the laboratory of Cell Culture Technology of the University of Applied Science, the Cyano Knights selected cyanobacteria because of its extreme ruggedness. Here on Earth, the bacteria lives in conditions that are hostile to other life forms, hence why they seemed like the perfect candidate.

As the team leader Robert P. Schröder, said to astrowatch.net: “Cyanobacteria do live in conditions on Earth where no life would be expected. You find them everywhere on our planet! It is the first step on Mars to test microorganisms.”

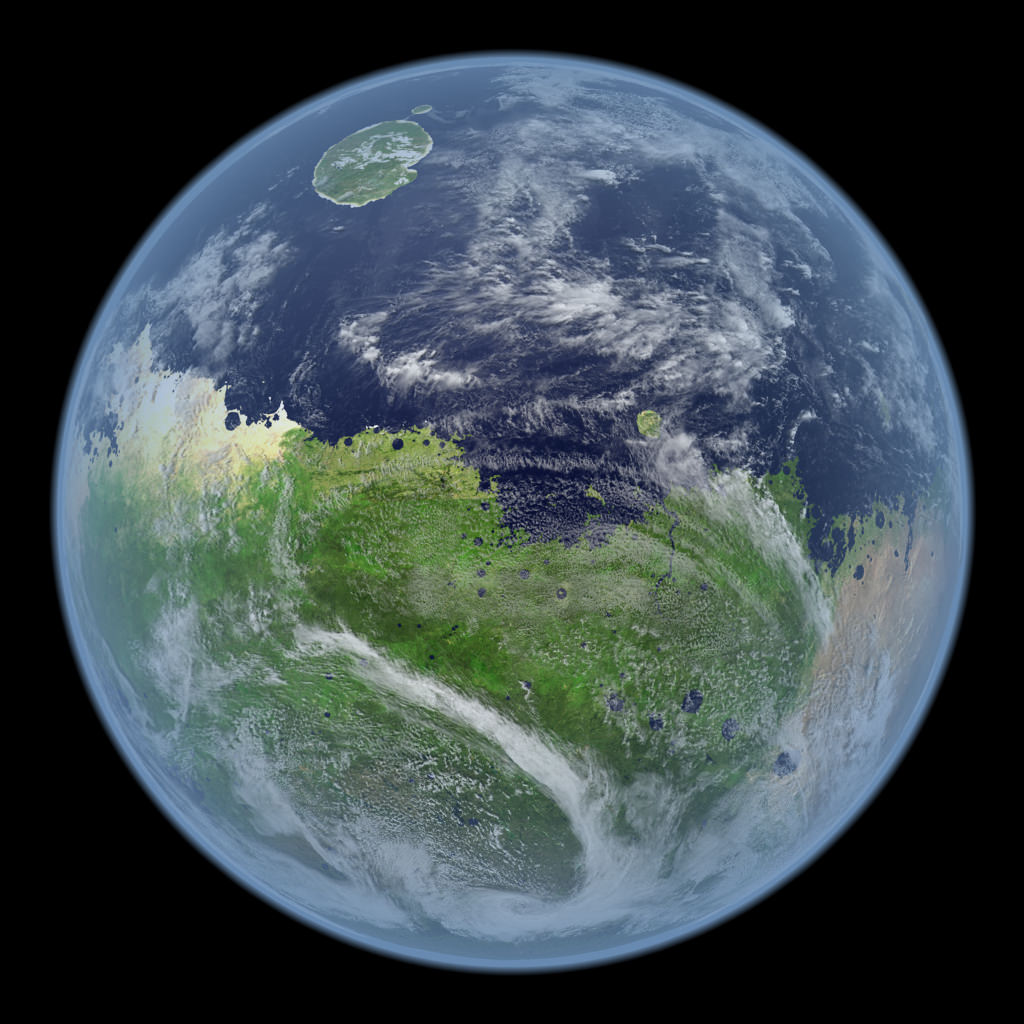

The other reason for sending cyanobacteria to Mars, in advance of humans, is the biological function they perform. As an organism that produces oxygen gas through photosynthesis to obtain nutrients, cyanobacteria are thought to have played a central role in the evolution of Earth’s atmosphere.

It is estimated that 2.7 billion years ago, they were pivotal in converting it from a toxic fume to the nitrogen and oxygen-rich one that we all know and love. This, in turn, led to the formation of the ozone layer which blocks out harmful UV rays and allowed for the proliferation of life.

According to their project description, the cyanobacteria, once introduced, will “deliver oxygen made of their photosynthesis, reducing carbon dioxide and produce an environment for living organisms like us. Furthermore, they can supply food and important vitamins for a healthy nutrition.”

Of course, the team is not sure how much of the bacteria will be needed to make a dent in Mars’ carbon-rich atmosphere, nor how much of the oxygen could be retained. But much like the other teams taking part in this competition, the goal here is to find out how terrestrial organisms will fare in the Martian environment.

The Cyano Knights hope that one day, manned mission will be able to take advantage of the oxygen created by these bacteria by either combining it with nitrogen to create breathable air, or recuperating it for consumption over and over again.

Not only does their project call for the use of existing technology, it also takes advantage of studies being conducted by NASA and other space agencies. As it says on their team page: “On the international space station they do experiments with cyanobacteria too. So let us take it to the next level and investigate our toughest life form on Mars finding the best survival species for mankind! We are paving the way for future Mars missions, not only to have breathable air!”

Other concepts include germinating seeds on Mars to prove that it is possible to grow plants there, building a miniature greenhouse, measuring the impact of cosmic surface and solar radiation on the surface, and processing urine into water.

All of these projects are aimed at obtaining data that will contribute to our understanding of the Martian landscape and be vital to any human settlements or manned missions there in the future.

For more information on the teams taking part in the competition, and to vote for who you would like to win, visit the Mars One University Competition page. Voting submission will be accepted until Dec. 31, 2014 and the winning university payload will be announced on Jan. 5, 2015.

Further Reading: CyanoKnights, MarsOne University Competition