Psst! Ever spy the planet Mercury? The most bashful of all the naked eye planets makes its best dawn appearance of 2014 this weekend for northern hemisphere observers. And not only will Mercury be worth getting up for, but you’ll also stand a chance at nabbing that most elusive of astronomical phenomena — the zodiacal light — from a good dark sky sight.

DST note: This post was written whilst we we’re visiting Arizona, a land that, we’re happy to report, does not for the most part observe the archaic practice of Daylight Saving Time. Life goes on, zombies do not arise, and trains still run on time. In the surrounding world of North America, however, don’t forget to “fall back” one hour on Sunday morning, November 2nd. I know, I know. Trust me, we didn’t design the wacky system we’re stuck with today. All times noted below post-shift reflect this change, but it also means that you’ll have to awaken an hour earlier Sunday November 2nd onwards to begin your astronomical vigil for Mercury!

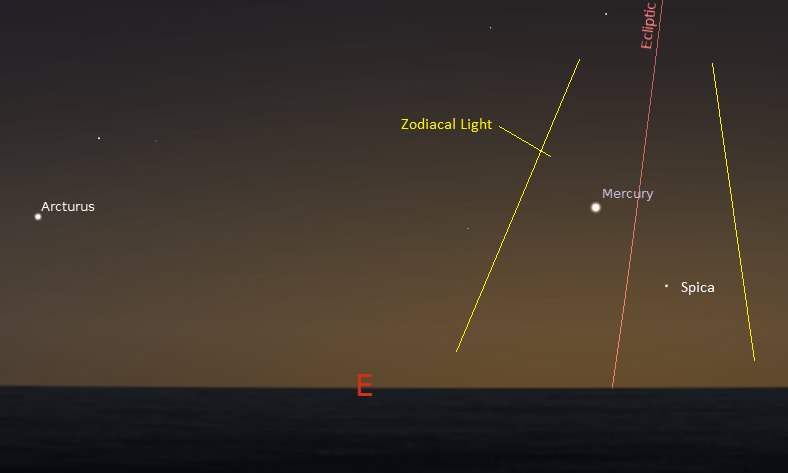

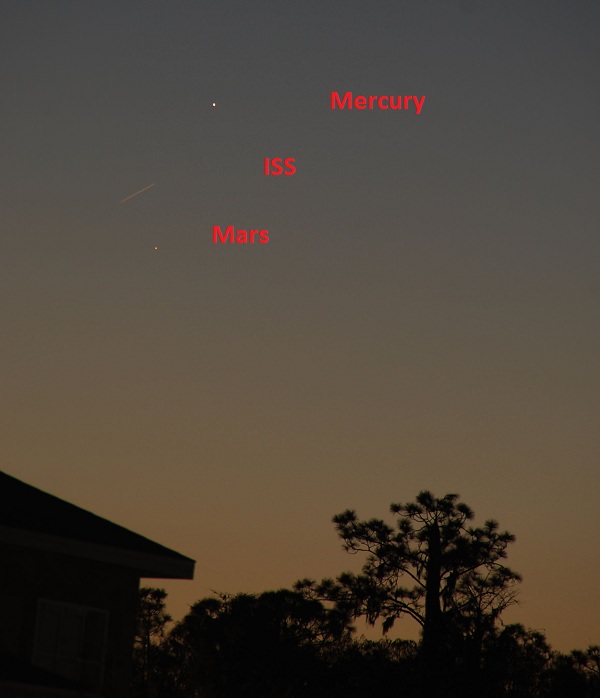

Mercury starts the month of November reaching greatest elongation on Saturday, November 1st at 18.7 degrees west of the Sun at 13:00 Universal Time UT/09:00 EDT. Look for Mercury about 10 degrees above the eastern horizon 40 minutes before sunrise. The planet Jupiter and the stars Denebola and Regulus make good morning guideposts to trace the line of the ecliptic down to the horizon to find -0.3 magnitude Mercury.

Sweeping along the horizon with binoculars, you may just be able to spy +0.2 magnitude Arcturus at a similar elevation to the northwest. The +1st magnitude star Spica also sits to Mercury’s lower right. Mercury passes 4.2 degrees north of Spica on November 4th while both are still about 18 degrees from the Sun, making for a good study in contrast.

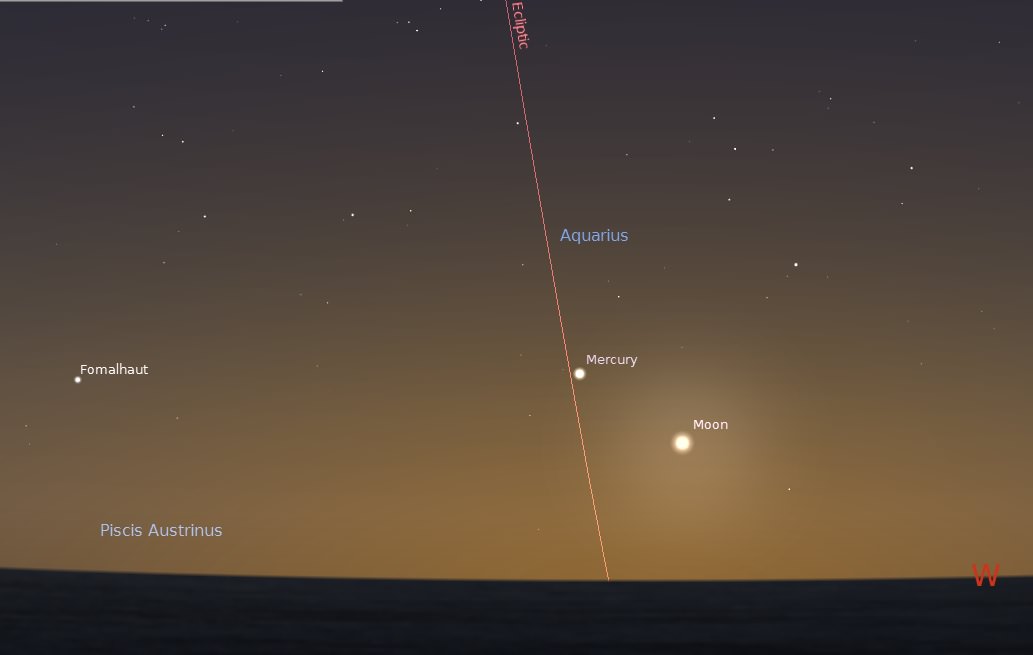

Later in the month, the old waning crescent Moon will present a challenge as it passes 2.1 degrees north of Mercury on November 21st, though both will only be 9 degrees from the Sun on this date.

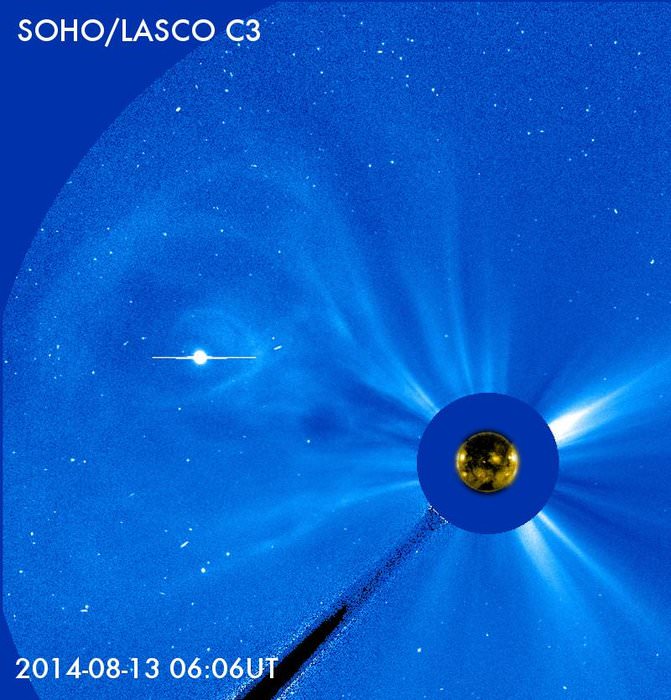

Mercury also passes 1.6 degrees south of Saturn November 26th, but both are only 7 degrees from the Sun and unobservable at this point. But don’t despair, as you can always watch all of the planetary conjunction action via SOHO’s sunward staring LASCO C3 camera, which has a generous 15 degree field of view.

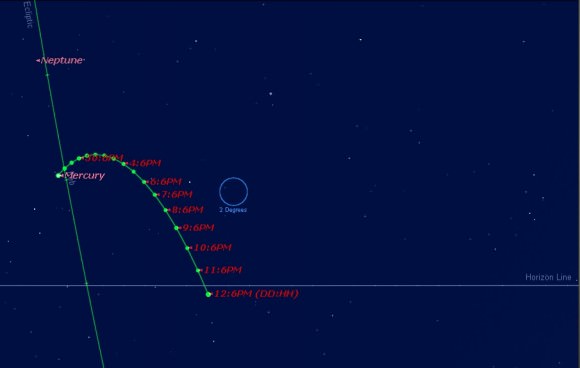

At the eyepiece, Mercury starts off the month of November as a 57% illuminated gibbous disk about 7” in diameter. This will change to a 92% illuminated disk 5″ across on November 15th, as the planet races towards superior conjunction on the far side of the Sun on December 8th. As with Venus, Mercury always emerges in the dawn sky as a crescent headed towards full phase, and the cycle reverses for both planets when they emerge in the dusk sky.

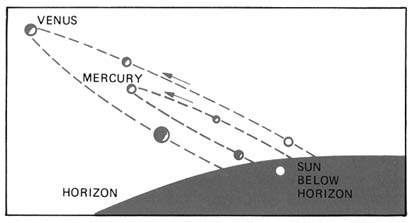

Why aren’t all appearances of Mercury the same? Mercury orbits the Sun once every 88 days, making greatest elongations of Mercury far from uncommon: on average, we get three dawn and three dusk apparitions of the innermost world per year, with a maximum of seven total possible. Two main factors come into play to assure that not all appearances of Mercury are created equal.

One is the angle of the ecliptic, which is the imaginary plane of our solar system that planets roughly follow traced out by the Earth’s orbit. In northern hemisphere Fall, this angle is at its closest to perpendicular at dawn, and the dusk angle is most favorable in the Spring. In the southern hemisphere, the situation is reversed. This serves to place Mercury as high as possible out of the atmospheric murk during favorable times, and shove it down into near invisibility during others.

The second factor is Mercury’s orbit. Mercury has the most elliptical orbit of any planet in our solar system at a value of 20.5% (0.205), with an aphelion of 69.8 million kilometres and perihelion 46 million kilometres from the Sun. This plays a more complicated role, as an elongation near perihelion only sees the planet venture 18.0 degrees from the Sun, while aphelion can see the planet range up to 27.8 degrees away. However, this distance variation also leads to noticeable changes in brightness that works to the advantage of Mercury spotters in the opposite direction. Mercury shines as bright as magnitude -0.3 at closer apparitions, to a full magnitude fainter at more distant ones at +0.7.

In the case of this weekend, greatest elongation for Mercury occurs just a week after perihelion, which transpired on October 25th.

Mercury is also worth keeping an eye on in coming years, as it will also transit the Sun for the first time since 2006 on May 9th, 2016. This will be visible for Europe and North America. We always thought it a bit strange that while rarer transits of Venus have yet to make their sci-fi theatrical debut, a transit of Mercury does crop up in the film Sunshine.

The first week of November is also a fine time to try and spy the zodiacal light. This is a cone-shaped glow following the plane of the ecliptic, resulting from sunlight backscattered across a dispersed layer of interplanetary dust. The zodiacal light was a common sight for us from the dark skies of Arizona, often rivaling the distant glow of Tucson over the mountains. The zodiacal light vanished from our view after moving to the humid and often light polluted U.S. East Coast, though we’re happy to report that we can once again spy it as we continue to traverse the U.S. southwest this Fall.

None other than rock legend Brian May of Queen fame wrote his PhD dissertation on the zodiacal light and the distribution and relative velocity of dust particles along the plane of the solar system. Having a dark site and a clear flat horizon is key to nabbing this bonus to your quest to cross Mercury off your life list this weekend!