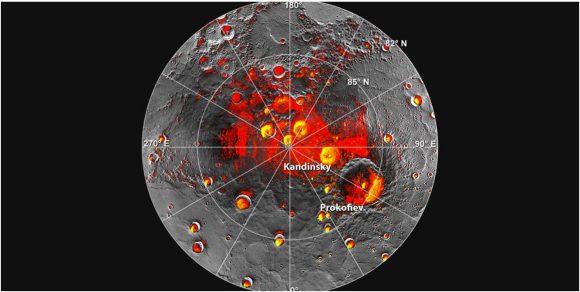

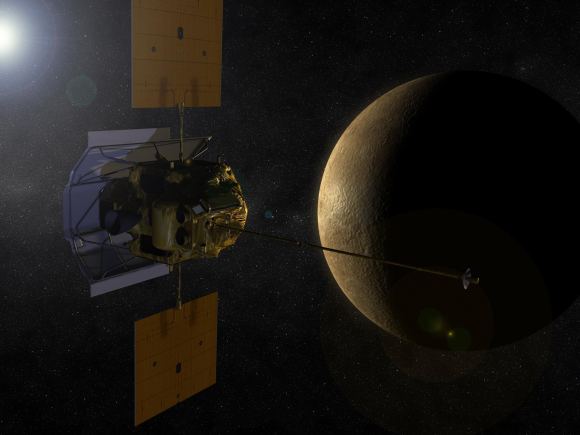

Back in 2012, scientists were delighted to discover that within the polar regions of Mercury, vast amounts of water ice were detected. While the existence of water ice in this permanently-shaded region had been the subject of speculation for about 20 years, it was only after the Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry, and Ranging (MESSENGER) spacecraft studied the polar region that this was confirmed.

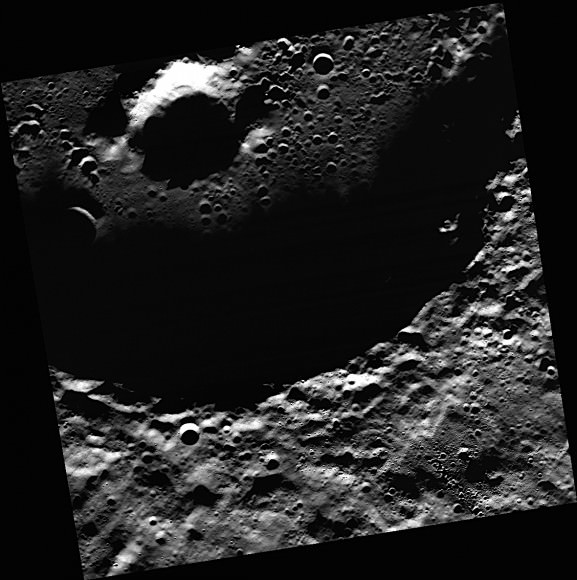

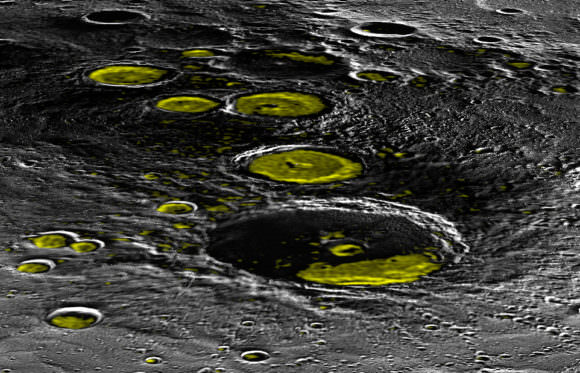

Based on the MESSENGER data, it was estimated that Mercury could have between 100 billion to 1 trillion tons of water ice at both poles, and that the ice could be up to 20 meters (65.5 ft) deep in places. However, a new study by a team of researchers from Brown University indicates that there could be three additional large craters and many more smaller ones in the northern polar region that also contain ice.

The study, titled “New Evidence for Surface Water Ice in Small-Scale Cold Traps and in Three Large Craters at the North Polar Region of Mercury from the Mercury Laser Altimeter“, was recently published in the Geophysical Research Letters. Led by Ariel Deutsch, a NASA ASTAR Fellow and a PhD candidate at Brown University, the team considered how small-scale deposits could dramatically increase the overall amount of ice on Mercury.

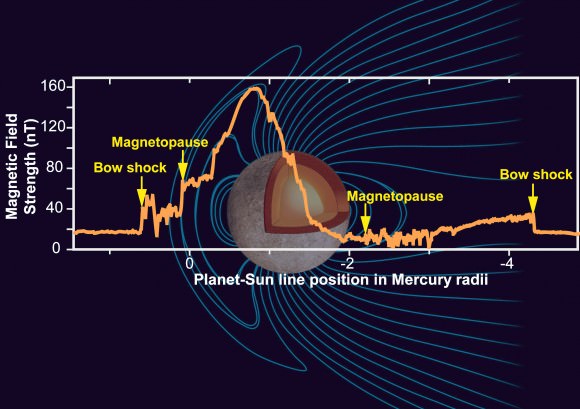

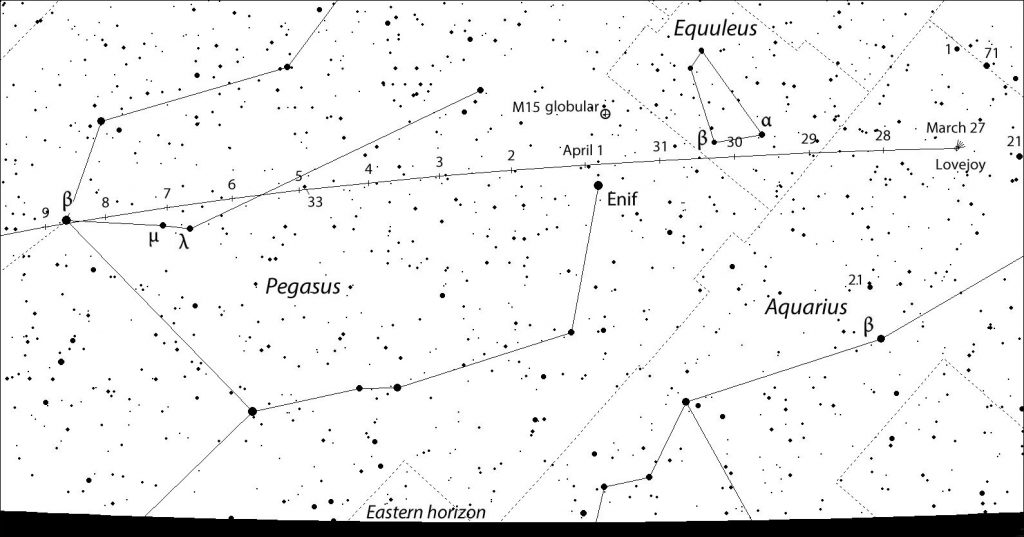

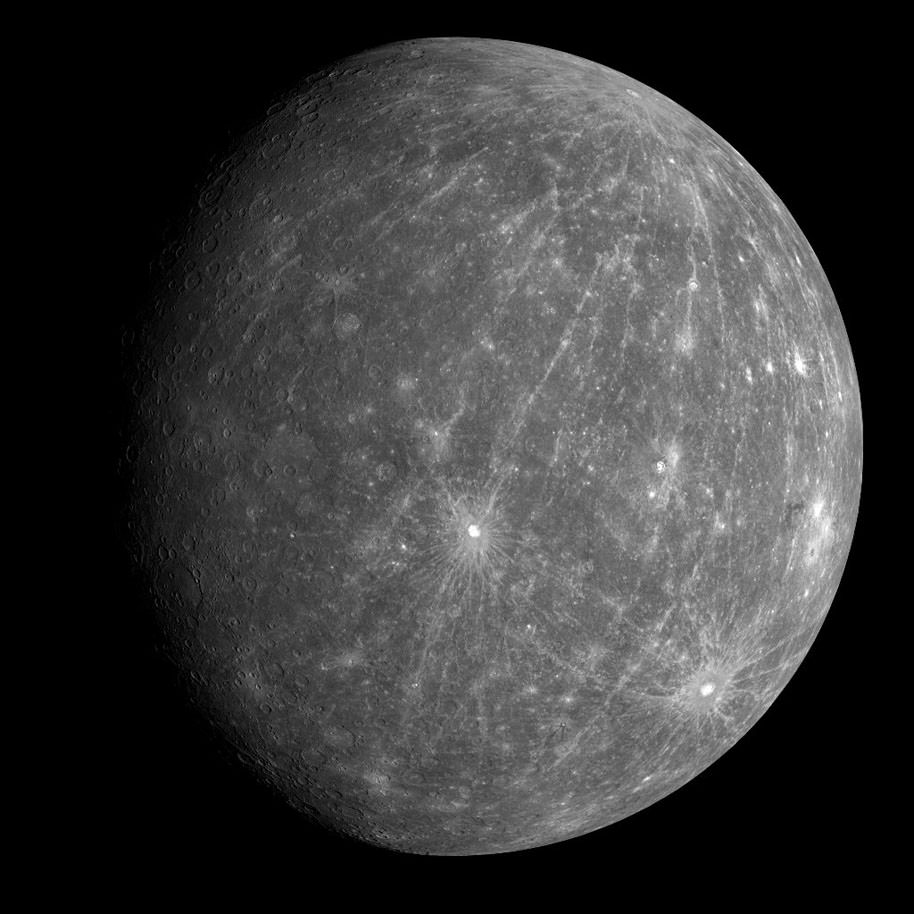

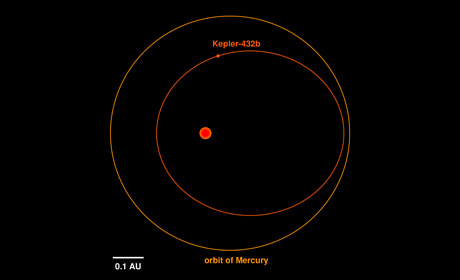

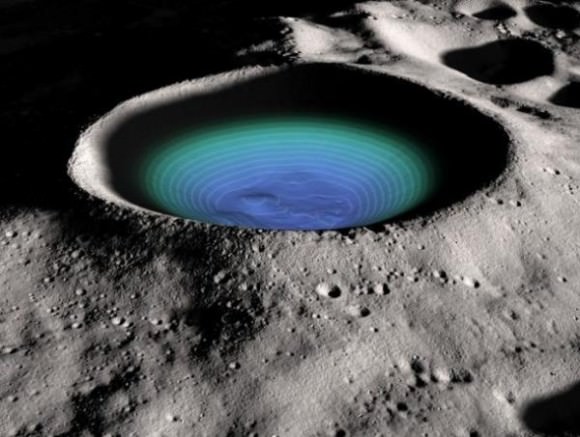

Despite being the closest planet to the Sun, and experiencing scorching surface temperatures on its Sun-facing side, Mercury’s low axial tilt means that its polar regions are permanently shaded and experience average temperatures of about 200 K (-73 °C; -100 °F). The idea that ice might exist in these regions dates back to the 1990s, when Earth-based radar telescopes detected highly reflective spots within the polar craters.

This was confirmed when the MESSENGER spacecraft detected neutron signals from the planet’s north pole that were consistent with water ice. Since that time, it has been the general consensus that Mercury’s surface ice was confined to seven large craters. But as Ariel Deutsch explained in a Brown University press statement, she and her team sought to look beyond them:

“The assumption has been that surface ice on Mercury exists predominantly in large craters, but we show evidence for these smaller-scale deposits as well. Adding these small-scale deposits to the large deposits within craters adds significantly to the surface ice inventory on Mercury.”

For the sake of this new study, Deutsch was joined by Gregory A. Neumann, a research scientist from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, and James W. Head. In addition to being a professor the Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences at Brown, Head was also a co-investigator for the MESSENGER and the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter missions.

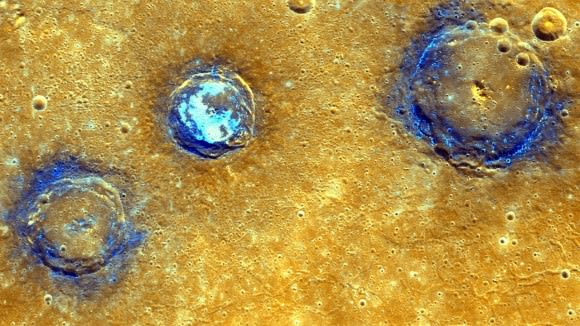

Together, they examined data from MESSENGER’s Mercury Laser Altimeter (MLA) instrument. This instrument was used by MESSENGER to measure the distance between the spacecraft and Mercury, the resulting data being then used to create detailed topographical maps of the planet’s surface. But in this case, the MLA was used to measure surface reflectance, which indicated the presence of ice.

As an instrument specialist with the MESSENGER mission, Neumann was responsible for calibrating the altimeter’s reflectance signal. These signals can vary based on whether the measurements are taken from overhead or at an angle (the latter of which is refereed to as “off-nadir” readings). Thanks to Neumann’s adjustments, researchers were able to detect high-reflectance deposits in three more large craters that were consistent with water ice.

According to their estimates, these three craters could contain ice sheets that measure about 3,400 square kilometers (1313 mi²). In addition, the team also looked at the terrain surrounding these three large craters. While these areas were not as reflective as the ice sheets inside the craters, they were brighter than the Mercury’s average surface reflectance.

Beyond this, they also looked at altimeter data to seek out evidence of smaller scale deposits. What they found was four smaller craters, each with diameters of less than 5 km (3 mi), which were also more reflective than the surface. From this, they deduced that there were not only more large deposits of ice that were previously undiscovered, but likely many smaller “cold traps” where ice could exist as well.

Between these three newly-discovered large deposits, and what could be hundreds of smaller deposits, the total volume of ice on Mercury could be considerably more than we previously thought. As Deutsch said:

“We suggest that this enhanced reflectance signature is driven by small-scale patches of ice that are spread throughout this terrain. Most of these patches are too small to resolve individually with the altimeter instrument, but collectively they contribute to the overall enhanced reflectance… These four were just the ones we could resolve with the MESSENGER instruments. We think there are probably many, many more of these, ranging in sizes from a kilometer down to a few centimeters.”

In the past, studies of the lunar surface also confirmed the presence of water ice in its cratered polar regions. Further research indicated that outside of the larger craters, small “cold traps”could also contain ice. According to some models, accounting for these smaller deposits could effectively double estimates on the total amounts of ice on the Moon. Much the same could be true for Mercury.

But as Jim Head (who also served as Deutsch Ph.D. advisor for this study) indicated, this work also adds a new take to the critical question of where water in the Solar System came from. “One of the major things we want to understand is how water and other volatiles are distributed through the inner Solar System—including Earth, the Moon and our planetary neighbors,” he said. “This study opens our eyes to new places to look for evidence of water, and suggests there’s a whole lot more of it on Mercury than we thought.”

In addition to indicating the Solar System may be more watery than previously suspected, the presence of abundant ice on Mercury and the Moon has bolstered proposals for building outposts on these bodies. These outposts could be capable of turning local deposits water ice into hydrazine fuel, which would drastically reduce the costs of mounting long-range missions throughout the Solar System.

On the less-speculative side of things, this study also offers new insights into how the Solar System formed and evolved. If water is far more plentiful today than we knew, it would indicate that more was present during the early epochs of planetary formation, presumably when it was being distributed throughout the Solar System by asteroids and comets.

Further Reading: Brown University, Geophysical Research Letters