Welcome back to Messier Monday! Today, we continue in our tribute to our dear friend, Tammy Plotner, by looking at the intermediate spiral galaxy known as Messier 66.

In the 18th century, while searching the night sky for comets, French astronomer Charles Messier kept noting the presence of fixed, diffuse objects he initially mistook for comets. In time, he would come to compile a list of approximately 100 of these objects, hoping to prevent other astronomers from making the same mistake. This list – known as the Messier Catalog – would go on to become one of the most influential catalogs of Deep Sky Objects.

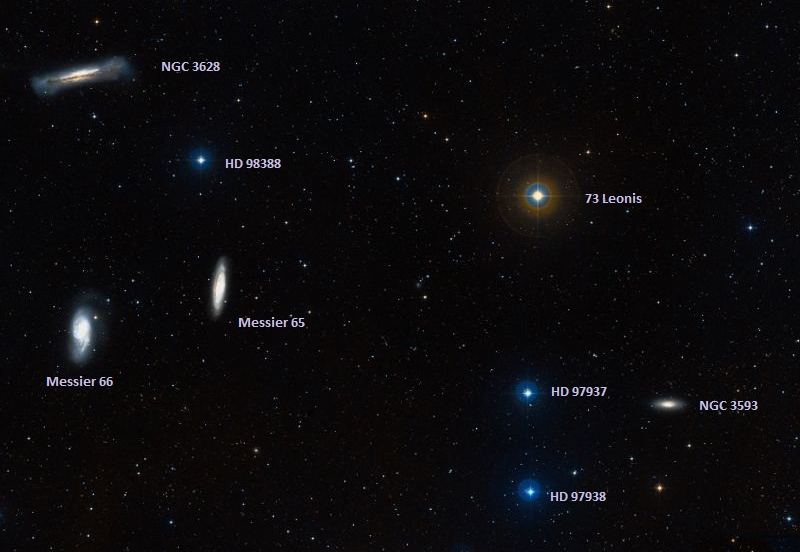

One of these objects is the intermediate elliptical galaxy known as Messier 66 (NGC 3627). Located about 36 million light-years from Earth in the direction of the Leo constellation, this galaxy measures 95,000 light-years in diameter. It is also the brightest and largest member of the Leo Triplet of galaxies and is well-known for its bright star clusters, dust lanes, and associated supernovae.

Description:

Enjoying life some 35 million light years from the Milky Way, the group known as the “Leo Trio” is home to bright galaxy Messier 66 – the easternmost of the two M objects. In the telescope or binoculars, you’ll find this barred spiral galaxy far more visible and much easier to see details within its knotted arms and bulging core.

Because of interaction with its neighboring galaxies, M66 shows signs of a extremely high central mass concentration as well as a resolved noncorotating clump of H I material apparently removed from one of the spiral arms. Even one of its spiral arms got it noted in Halton Arp’s collection of Peculiar Galaxies! So exactly what did it collide with?As Xiaolei Zhang (et al) indicated in a 1993 study:

“The combined CO and H I data provide new information, both on the history of the past encounter of NGC 3627 with its companion galaxy NGC 3628 and on the subsequent dynamical evolution of NGC 3627 as a result of this tidal interaction. In particular, the morphological and kinematic information indicates that the gravitational torque experienced by NGC 3627 during the close encounter triggered a sequence of dynamical processes, including the formation of prominent spiral structures, the central concentration of both the stellar and gas mass, the formation of two widely separated and outwardly located inner Lindblad resonances, and the formation of a gaseous bar inside the inner resonance. These processes in coordination allow the continuous and efficient radial mass accretion across the entire galactic disk. The observational result in the current work provides a detailed picture of a nearby interacting galaxy which is very likely in the process of evolving into a nuclear active galaxy. It also suggests one of the possible mechanisms for the formation of successive instabilities in postinteraction galaxies, which could very efficiently channel the interstellar medium into the center of the galaxy to fuel nuclear starburst and Seyfert activities.”

Ah, yes! Star forming regions… And what better way to look deeper than through the eyes of the Spitzer Space Telescope? As R. Kennicutt (University of Arizona) and the SINGS Team observed:

“M66’s blue core and bar-like structure illustrates a concentration of older stars. While the bar seems devoid of star formation, the bar ends are bright red and actively forming stars. A barred spiral offers an exquisite laboratory for star formation because it contains many different environments with varying levels of star-formation activity, e.g., nucleus, rings, bar, the bar ends and spiral arms. The SINGS image is a four-channel false-color composite, where blue indicates emission at 3.6 microns, green corresponds to 4.5 microns, and red to 5.8 and 8.0 microns. The contribution from starlight (measured at 3.6 microns) in this picture has been subtracted from the 5.8 and 8 micron images to enhance the visibility of the dust features.”

Messier 66 has also been deeply studied for evidence of forming super star clusters, too. As David Meier indicated:

“Super star clusters are thought to be precursors of globular clusters and are some of the most extreme star formation regions in the universe. They tend to occur in actively starbursting galaxies or near the cores of less active galaxies. Radio super star clusters cannot be seen in optical light because of extreme extinction, but they shine brightly in infrared and radio observations. We can be certain that there are many massive O stars in these regions because massive stars are required to provide the UV radiation that ionizes the gas and creates a thermally bright HII regions. Not many natal SSCs are currently known, so detection is an important science goal in its own right. In particular, very few SSCs are known in galactic disks. We need more detections to be able to make statistical statements about SSCs and fill in the mass range of forming star clusters. With more detections, we will be able to investigate the effects of other environments (e.g. bars, bubbles, and galactic interaction) on SSCs, which could potentially be followed up in the far future with the Square Kilometer Array to discover their effects on individual forming massive stars.”

But there’s still more. Try magnetic properties in M66’s spiral patterns. As M. Soida (et al) indicated in their 2001 study:

“By observing the interacting galaxy NGC 3627 in radio polarization we try to answer the question; to which degree does the magnetic field follow the galactic gas flow. We obtained total power and polarized intensity maps at 8.46 GHz and 4.85 GHz using the VLA in its compact D-configuration. In order to overcome the zero-spacing problems, the interferometric data were combined with single-dish measurements obtained with the Effelsberg 100-m radio telescope. The observed magnetic field structure in NGC 3627 suggests that two field components are superposed. One component smoothly fills the interarm space and shows up also in the outermost disk regions, the other component follows a symmetric S-shaped structure. In the western disk the latter component is well aligned with an optical dust lane, following a bend which is possibly caused by external interactions. However, in the SE disk the magnetic field crosses a heavy dust lane segment, apparently being insensitive to strong density-wave effects. We suggest that the magnetic field is decoupled from the gas by high turbulent diffusion, in agreement with the large Hi line width in this region. We discuss in detail the possible influence of compression effects and non-axisymmetric gas flows on the general magnetic field asymmetries in NGC 3627. On the basis of the Faraday rotation distribution we also suggest the existence of a large ionized halo around this galaxy.”

History of Observation:

Both M65 and M66 were discovered on the same night – March 1, 1780 – by Charles Messier, who described M66 as, “Nebula discovered in Leo; its light is very faint and it is very close to the preceding: They both appear in the same field in the refractor. The comet of 1773 and 1774 has passed between these two nebulae on November 1 to 2, 1773. M. Messier didn’t see them at that time, no doubt, because of the light of the comet.”

Both galaxies would be observed and cataloged by the Herschel family and further expounded upon by Admiral Smyth:

“A large elongated nebula, with a bright nucleus, on the Lion’s haunch, trending np [north preceding, NW] and sf [south following, SE]; this beautiful specimen of perspective lies just 3deg south-east of Theta Leonis. It is preceded at about 73s by another of a similar shape, which is Messier’s No. 65, and both are in the field at the same time, under a moderate power, together with several stars. They were pointed out by Mechain to Messier in 1780, and they appeared faint and hazy to him. The above is their appearance in my instrument.

“These inconceivably vast creations are followed, exactly on the same parallel, ar Delta AR=174s, by another elliptical nebula of even a more stupendous character as to apparent dimensions. It was discovered by H. [John Herschel], in sweeping, and is No. 875 in his Catalogue of 1830 [actually, probably an erroneous position for re-observed M66]. The two preceding of these singular objects were examined by Sir William Herschel, and his son [JH] also; and the latter says, “The general form of elongated nebulae is elliptic, and their condensation towards the centre is almost invariably such as would arise from the superposition of luminous elliptic strata, increasing in density towards the centre. In many cases the increase of density is obviously attended with a diminution of ellipticity, or a nearer approach to the globular form in the central than in the exterior strata.” He then supposes the general constitution of those nebulae to be that of oblate spheroidal masses of every degree of flatness from the sphere to the disk, and of every variety in respect of the law of their density, and ellipticity towards the centre. This must appear startling and paradoxical to those who imagine that the forms of these systems are maintained by forces identical with those which determine the form of a fluid mass in rotation; because, if the nebulae be only clusters of discrete stars, as in the greater number of cases there is every reason to believe them to be, no pressure can propagate through them. Consequently, since no general rotation of such a system as one mass can be supposed, Sir John suggests a scheme which he shows is not, under certain conditions, inconsistent with the law of gravitation. “It must rather be conceived,” he tells us, ” as a quiescent form, comprising within its limits an indefinite magnitude of individual constituents, which, for aught we can tell, may be moving one among the other, each animated by its own inherent projectile force, and deflected into an orbit more or less complicated, by the influence of that law of internal gravitation which may result from the compounded attractions of all its parts.”

Locating Messier 66:

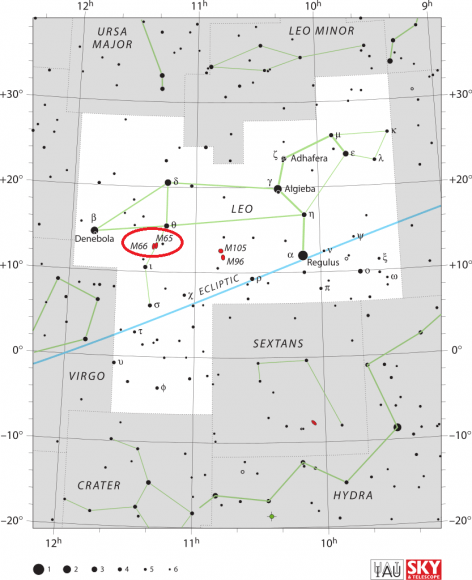

Even though you might think by its apparent visual magnitude that M66 wouldn’t be visible in small binoculars, you’d be wrong. Surprisingly enough, thanks to its large size and high surface brightness, this particular galaxy is very easy to spot directly between Iota and Theta Leonis. In even 5X30 binoculars under good conditions you’ll easy see both it and M65 as two distinct gray ovals.

A small telescope will begin to bring out structure in both of these bright and wonderful galaxies, but to get a hint at the “Trio” you’ll need at least 6″ in aperture and a good dark night. If you don’t spot them right away in binoculars, don’t be disappointed – this means you probably don’t have good sky conditions and try again on a more transparent night. The pair is well suited to modestly moonlit nights with larger telescopes.

May you equally be attracted to this galactic pair!

And here are the quick facts on M66 to help you get started:

Object Name: Messier 66

Alternative Designations: M66, NGC 3627, (a member of the) Leo Trio, Leo Triplet

Object Type: Type Sb Spiral Galaxy

Constellation: Leo

Right Ascension: 11 : 20.2 (h:m)

Declination: +12 : 59 (deg:m)

Distance: 35000 (kly)

Visual Brightness: 8.9 (mag)

Apparent Dimension: 8×2.5 (arc min)

We have written many interesting articles about Messier Objects here at Universe Today. Here’s Tammy Plotner’s Introduction to the Messier Objects, M1 – The Crab Nebula, and David Dickison’s articles on the 2013 and 2014 Messier Marathons.

Be to sure to check out our complete Messier Catalog. And for more information, check out the SEDS Messier Database.

Sources: