Welcome back to Messier Monday! In our ongoing tribute to the great Tammy Plotner, we take a look at that swirling, starry customer, the Whirlpool Galaxy!

During the 18th century, famed French astronomer Charles Messier noted the presence of several “nebulous objects” in the night sky. Having originally mistaken them for comets, he began compiling a list of them so that others would not make the same mistake he did. In time, this list (known as the Messier Catalog) would come to include 100 of the most fabulous objects in the night sky.

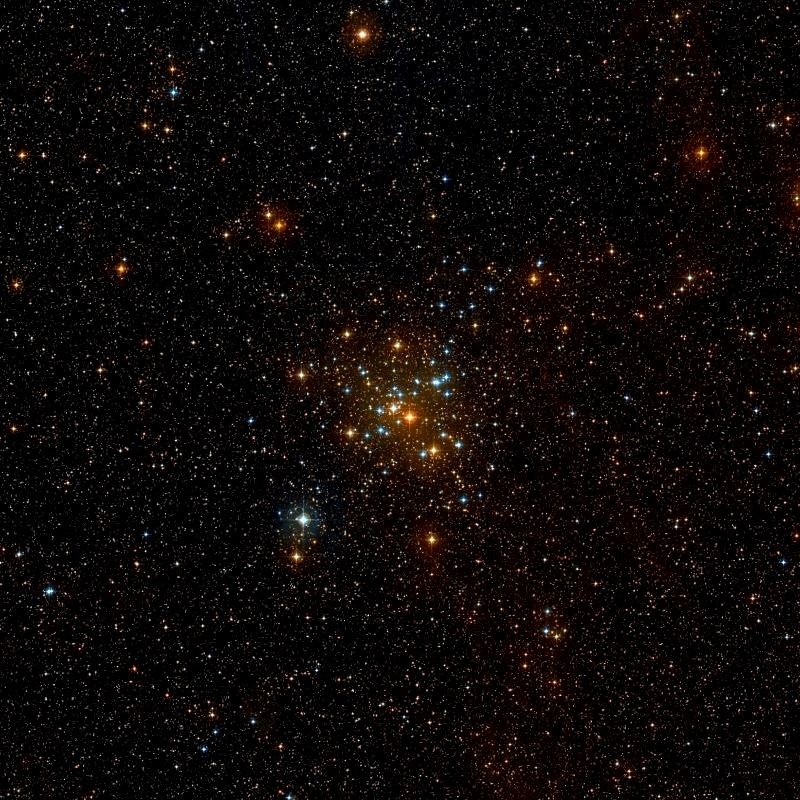

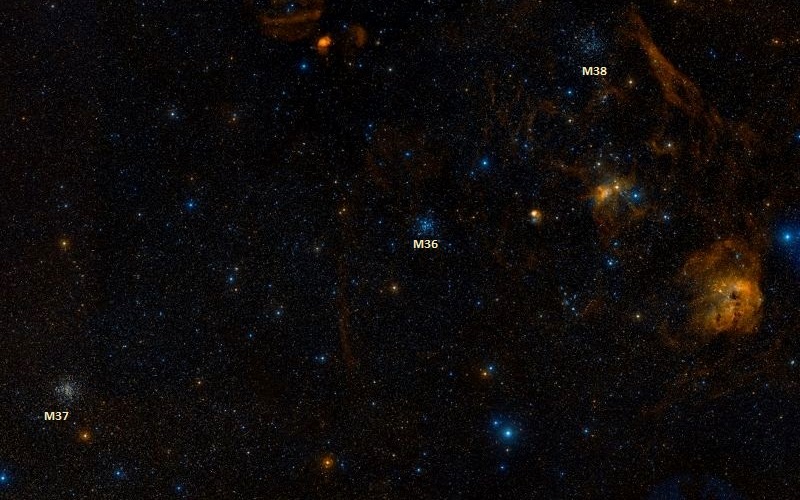

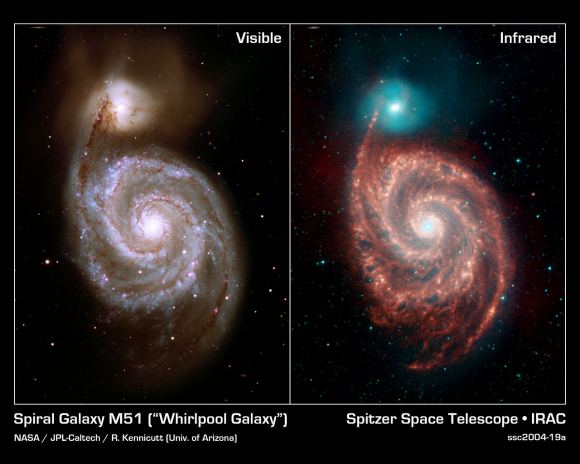

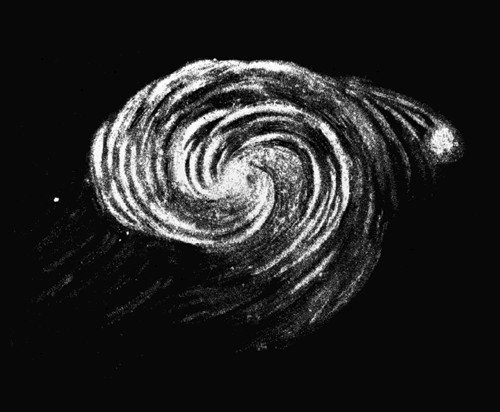

One of these is the spiral galaxy located in the constellation Canes Venatici known as the Whirlpool Galaxy (aka. Messier 51). Located between 19 and 27 million light-years from the Milky Way, this deep sky object was the very first to be classified as a spiral galaxy. It is also one of the best known galaxies among amateur astronomers, and is easily observable using binoculars and small telescopes.

Description:

Located some 37 million light years away, M51 is the largest member of a small group of galaxies, which also houses M63 and a number of fainter galaxies. To this time, the exact distance of this group isn’t properly known… Even when a 2005 supernova event should have helped astronomers to correctly calculate! As K. Takats stated in a study:

“The distance to the Whirlpool galaxy (M51, NGC 5194) is estimated using published photometry and spectroscopy of the Type II-P supernova SN 2005cs. Both the expanding photosphere method (EPM) and the standard candle method (SCM), suitable for SNe II-P, were applied. The average distance (7.1 +/- 1.2 Mpc) is in good agreement with earlier surface brightness fluctuation and planetary nebulae luminosity function based distances, but slightly longer than the distance obtained by Baron et al. for SN 1994I via the spectral fitting expanding atmosphere method. Since SN 2005cs exhibited low expansion velocity during the plateau phase, similarly to SN 1999br, the constants of SCM were recalibrated including the data of SN 2005cs as well. The new relation is better constrained in the low-velocity regime, that may result in better distance estimates for such SNe.”

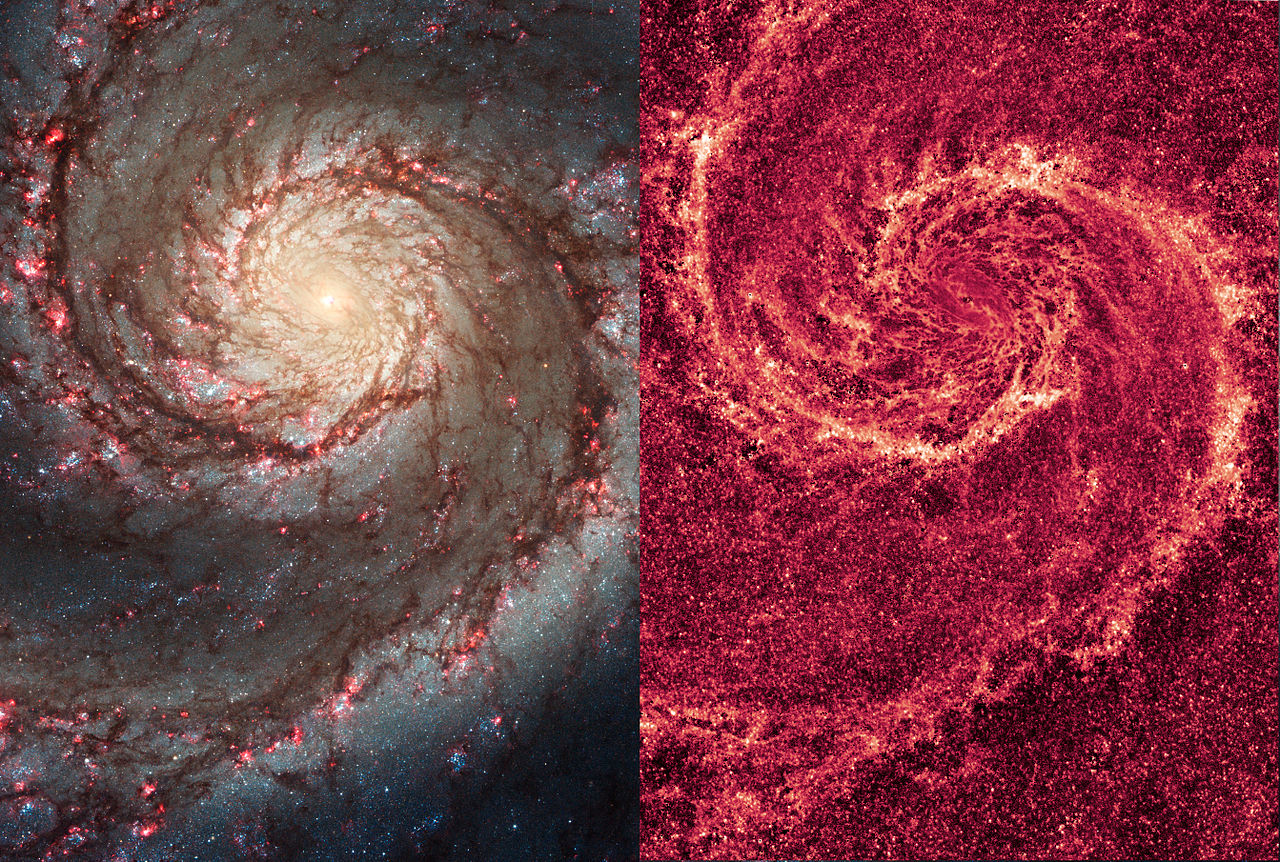

Of course, one of the most outstanding features of the Whirlpool Galaxy is its beautiful spiral structure – perhaps result of the close interaction between it and its companion galaxy NGC 5195? As S. Beckwith,

“This sharpest-ever image of the Whirlpool Galaxy, taken in January 2005 with the Advanced Camera for Surveys aboard NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, illustrates a spiral galaxy’s grand design, from its curving spiral arms, where young stars reside, to its yellowish central core, a home of older stars. At first glance, the compact galaxy appears to be tugging on the arm. Hubble’s clear view, however, shows that NGC 5195 is passing behind the Whirlpool. The small galaxy has been gliding past the Whirlpool for hundreds of millions of years. As NGC 5195 drifts by, its gravitational muscle pumps up waves within the Whirlpool’s pancake-shaped disk. The waves are like ripples in a pond generated when a rock is thrown in the water. When the waves pass through orbiting gas clouds within the disk, they squeeze the gaseous material along each arm’s inner edge. The dark dusty material looks like gathering storm clouds. These dense clouds collapse, creating a wake of star birth, as seen in the bright pink star-forming regions. The largest stars eventually sweep away the dusty cocoons with a torrent of radiation, hurricane-like stellar winds, and shock waves from supernova blasts. Bright blue star clusters emerge from the mayhem, illuminating the Whirlpool’s arms like city streetlights.”

But there were more surprises just waiting to be found – like a black hole, surrounded by a ring of dust. What makes it even more odd is a secondary ring crosses the primary ring on a different axis, a phenomenon that is contrary to expectations and a pair of ionization cones extend from the axis of the main dust ring. As H. Ford,

“This image of the core of the nearby spiral galaxy M51, taken with the Wide Field Planetary camera (in PC mode) on NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, shows a striking , dark “X” silhouetted across the galaxy’s nucleus. The “X” is due to absorption by dust and marks the exact position of a black hole which may have a mass equivalent to one-million stars like the sun. The darkest bar may be an edge-on dust ring which is 100 light-years in diameter. The edge-on torus not only hides the black hole and accretion disk from being viewed directly from earth, but also determines the axis of a jet of high-speed plasma and confines radiation from the accretion disk to a pair of oppositely directed cones of light, which ionize gas caught in their beam. The second bar of the “X” could be a second disk seen edge on, or possibly rotating gas and dust in MS1 intersecting with the jets and ionization cones.”

History of Observation:

The Whirlpool Galaxy was first discovered by Charles Messier on October 13th, 1773 and re-observed again for his records on January 11th, 1774. As he wrote of his discovery in his notes:

“Very faint nebula, without stars, near the eye of the Northern Greyhound [hunting dog], below the star Eta of 2nd magnitude of the tail of Ursa Major: M. Messier discovered this nebula on October 13, 1773, while he was watching the comet visible at that time. One cannot see this nebula without difficulties with an ordinary telescope of 3.5 foot: Near it is a star of 8th magnitude. M. Messier reported its position on the Chart of the Comet observed in 1773 & 1774. It is double, each has a bright center, which are separated 4’35”. The two “atmospheres” touch each other, the one is even fainter than the other.”

It would be his faithful friend and assistant, Pierre Mechain who would discover NGC 5195 on March 21st, 1781. Even though it would be many, many years before it was proven that galaxies were indeed independent systems, historic astronomers were much, much sharper than we gave them credit for. Sir William Herschel would observe M51 many times, but it would be his son John who would be the very first to comment on M51’s scheme:

“This very singular object is thus described by Messier: – “Nebuleuse sans etoiles.” “On ne peut la voir que difficilement avec une lunette ordinaire de 3 1/2 pieds.” “Elle est double, ayant chacune un centre brillant eloigne l’un de l’autre de 4′ 35″. Les deux atmospheres se touchent.” By this description it is evident that the peculiar phenomena of the nebulous ring which encircles the central nucleus had escaped his observation, as might have been expected from the inferior light of his telescopes. My Father describes it in his observations of Messier’s nebulae as a bright round nebula, surrounded by a halo or glory at a distance from it, and accompanied by a companion; but I do not find that the partial subdivision of the ring into two branches throughout its south following limb was noticed by him. This is, however, one of its most remarkable and interesting features. Supposing it to consist of stars, the appearance it would present to a spectator placed on a planet attendant on one of them eccentrically situated towards the north preceding quarter of the central mass, would be exactly similar to that of our Milky Way, traversing in a manner precisely analogous the firmament of large stars, into which the central cluster would be seen projected, and (owing to its distance) appearing, like it, to consist of stars much smaller than those in other parts of the heavens. Can it, then, be that we have here a brother-system bearing a real physical resemblance and strong analogy of structure to our own? Were it not for the subdivision of the ring, the most obvious analogy would be that of the system of Saturn, and the idea of Laplace respecting the formation of that system would be powerfully recalled by this object. But it is evident that all idea of symmetry caused by rotation on an axis must be relinquished, when we consider that the elliptic form of the inner subdivided portion indicates with extreme probability an elevation of that portion above the plane of the rest, so that the real form must be that of a ring split through half its circumference, and having the split portions set asunder at an angle of about 45 deg each to the plane of the other.”

As with other Messier Objects, Admiral Smyth also had some insightful and poetic observations to add. As he wrote of this galaxy in September of 1836:

“We have then an object presenting an amazing display of the uncontrollable energies of the Omnipotence, the contemplation of which compels reason and admiration to yield to awe. On the outermost verge of telescopic reach we perceive a stellar universe similar to that to which we belong, whose vast amplitudes no doubt are peopled with countless numbers of percipient beings; for those beautiful orbs cannot be considered as mere masses of inert matter.

And it is interesting to know that, if there be intelligent existence, an astronomer gazing at our distant universe, will see it, with a good telescope, precisely under the lateral aspect which theirs presents to us. But after all what do we see? Both that wonderful universe, our own, and all which optical assistance has revealed to us, may be only the outliers of a cluster immensely more numerous.

The millions of suns we perceive cannot comprise the Creator’s Universe. There are no bounds to infinitude; and the boldest views of the elder Herschel only placed us as commanding a ken whose radius is some 35,000 times longer than the distance of Sirius from us. Well might the dying Laplace explain: “That which we know is little; that which we know not is immense.”

Lord Rosse would continue on in 1844 with his 6-feet (72-inch) aperture, 53-ft FL “Leviathan” telescope, but he was a man of fewer words.

“The greater part of the observations were made when the eye was affected by lamp-light, which made it difficult to estimate correctly the centre of the nucleus; it was of importance that no time should be unnecessarily spent, and after the lamp had been used a new measure was taken, as it was judged that the object was sufficiently seen. With the brighter stars this would frequently happen before the nucleus was well defined, as all impediments to vision seem to affect nebulae much more than stars the light of which would be estimated as of the same intensity. In the foregoing list the greatest discrepancies are in the measures of bright objects, and this is probably the proper account of it. No stars have been inserted in the sketch which are not in the table of the measurements. The general appearance of the object would have been better given if the minute stars had been put in from the eye-sketch, but it would have created confusion.”

May the stars from this distant island universe fill your eyes!

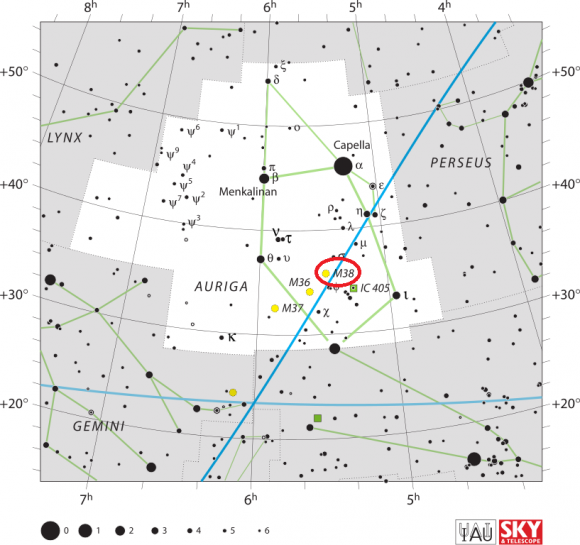

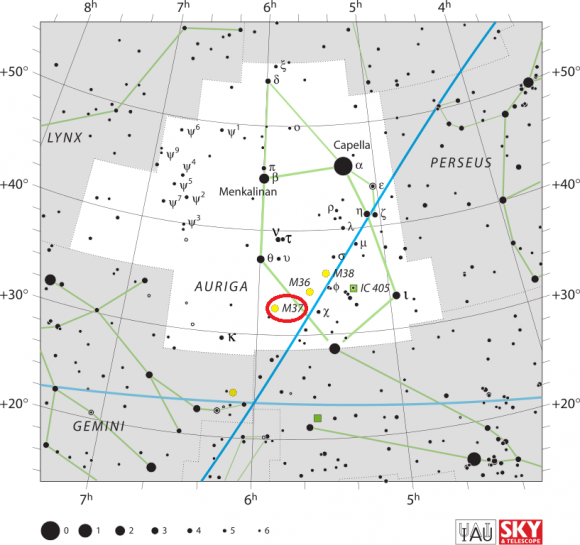

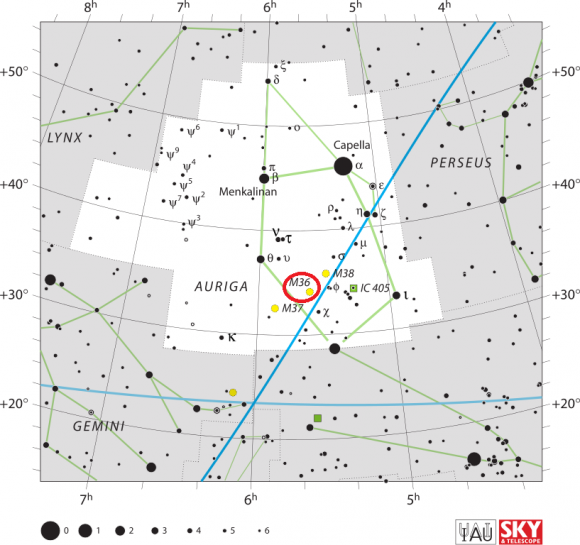

Locating Messier 51:

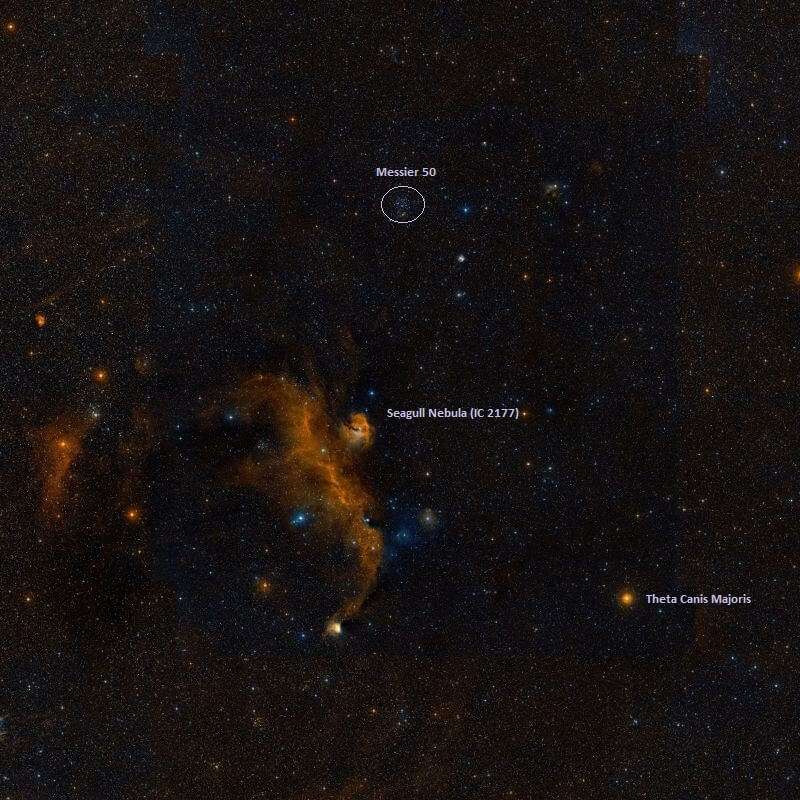

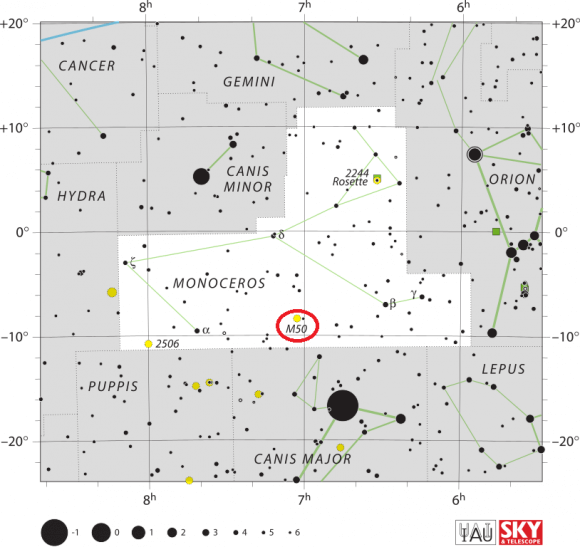

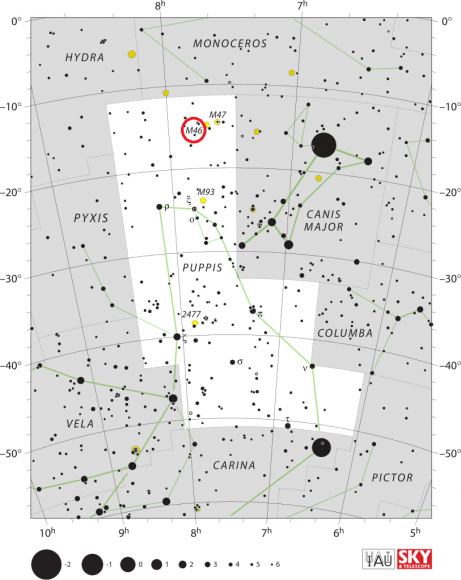

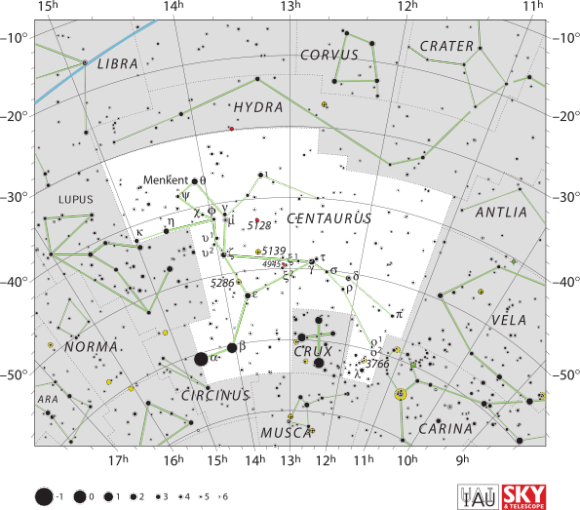

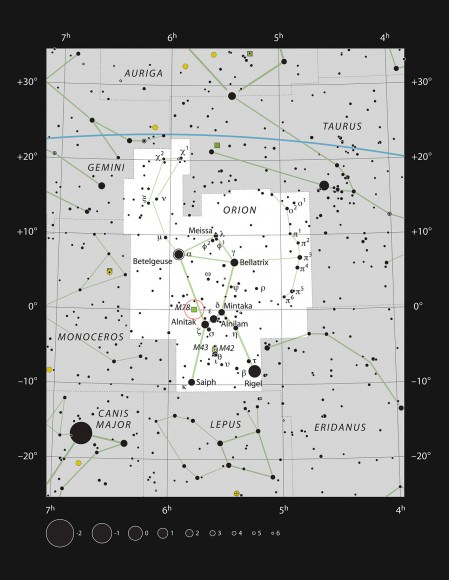

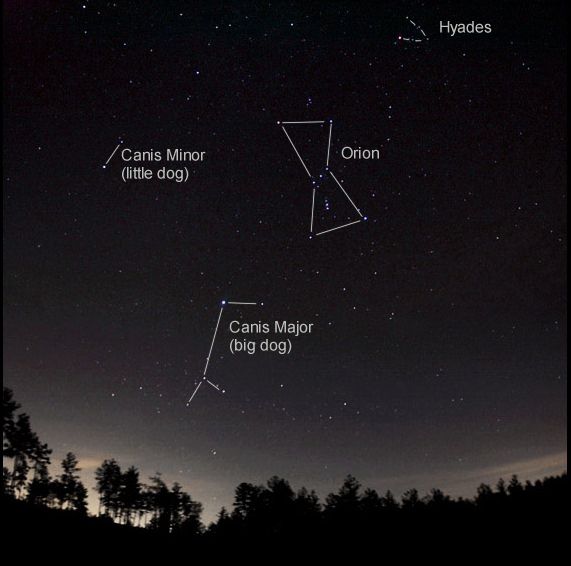

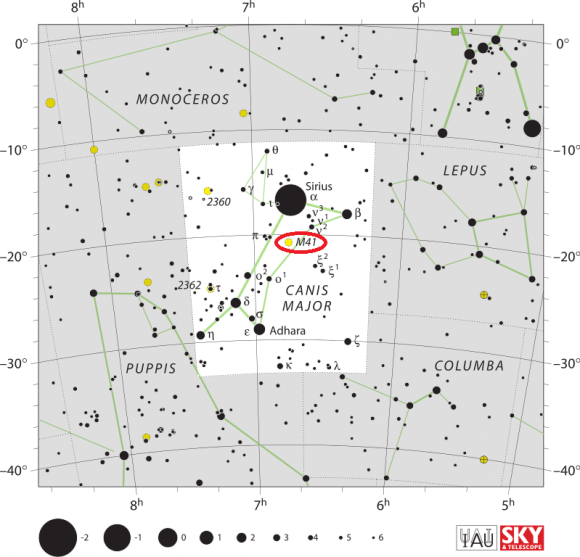

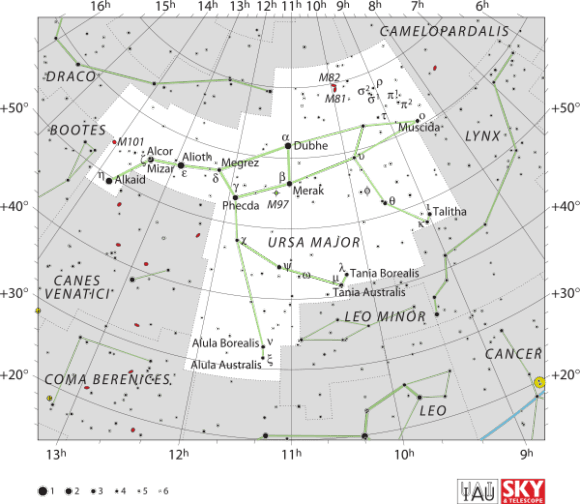

Locating M51 isn’t too hard if you have dark skies, but this particular galaxy is very difficult where light pollution of moonlight is present. To find it, start with Eta UM, the star at the handle of the Big Dipper. In the finderscope or binoculars, you’ll clearly see 24 UM to the southwest. Now, center your optics there and move slowly southwest towards Cor Caroli (Alpha CVn) and you’ll find it!

In locations where skies are clear and dark, it is easy to see spiral structure in even small telescopes, or to make out the galaxy in binoculars – but even a change in sky conditions can hide it from a good location. Rich field telescopes with fast focal lengths to an outstanding job on this galaxy and companion and you may be able to make out the nucleus of both galaxies on a good night from even a bad location.

Object Name: Messier 51

Alternative Designations: M51, NGC 5194, The Whirlpool Galaxy

Object Type: Type Sc Galaxy

Constellation: Canes Venatici

Right Ascension: 13 : 29.9 (h:m)

Declination: +47 : 12 (deg:m)

Distance: 37000 (kly)

Visual Brightness: 8.4 (mag)

Apparent Dimension: 11×7 (arc min)

We have written many interesting articles about Messier Objects here at Universe Today. Here’s Tammy Plotner’s Introduction to the Messier Objects, , M1 – The Crab Nebula, M8 – The Lagoon Nebula, and David Dickison’s articles on the 2013 and 2014 Messier Marathons.

Be to sure to check out our complete Messier Catalog. And for more information, check out the SEDS Messier Database.

Sources: