The meteor shower drought ends this weekend.

The northern summer hemisphere meteor season is almost upon us. In a few weeks’ time, the Perseids — the “Old Faithful” of meteor showers — will be gracing night skies worldwide.

But the Perseids have an “opening act”- a meteor shower optimized for southern hemisphere skies known as the Delta Aquarids.

This year offers a mixed bag for this shower. The Delta Aquarids are expected to peak on July 30th and we should start seeing some action from this shower starting this weekend.

The Moon, however, also reaches Last Quarter phase the day before the expected peak of the Delta Aquarids this year on July 29th at 1:43PM EDT/17:43 Universal Time (UT). This will diminish the visibility of all but the brightest meteors in the early morning hours of July 30th.

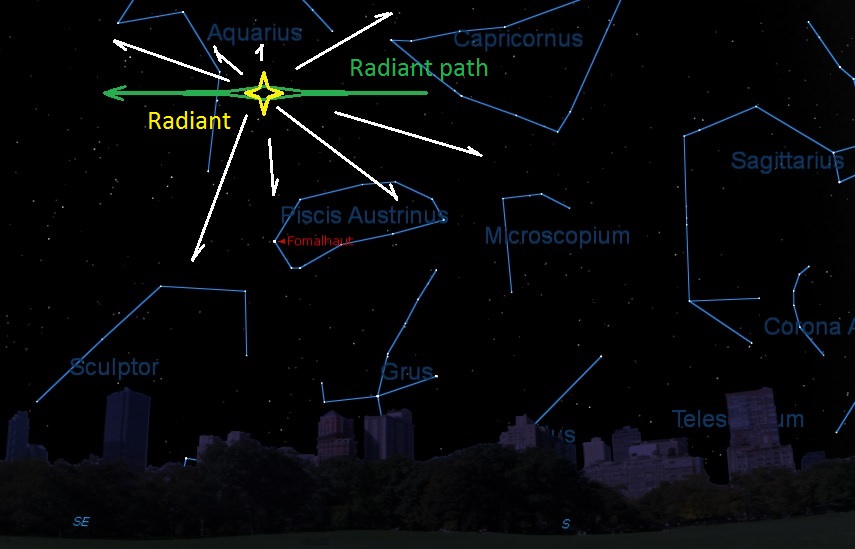

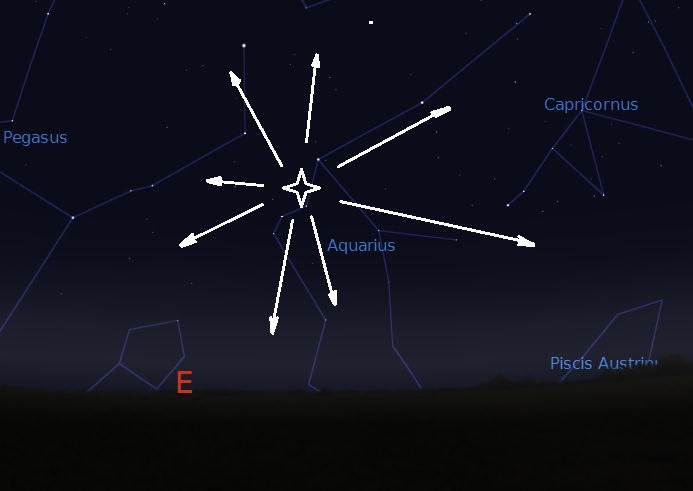

A cluster of meteor shower radiants also lies nearby. The Eta Aquarids emanate from a point near the asterism known as the “Water Jar” in the constellation Aquarius around May 5th. Another nearby but weaker shower known as the Alpha Capricornids are also currently active, with a zenithal hourly rate (ZHR) approaching the average hourly sporadic rate of 5. And speaking of which, the antihelion point, another source of sporadic meteors, is nearby in late July as well in eastern Capricornus.

The Delta Aquarids are caused by remnants of Comet 96P/Machholz colliding with Earth’s atmosphere. The short period comet was only discovered in 1986 by amateur astronomer Donald Machholz. Prior to this, the source of the Delta Aquarids was a mystery.

The Delta Aquarids have a moderate atmospheric entry velocity (for a meteor shower, that is) around an average of 41 kilometres a second. They also have one of the lowest r values of a major shower at 3.2, meaning that they produce a disproportionately higher number of fainter meteors, although occasional brighter fireballs are also associated with this shower.

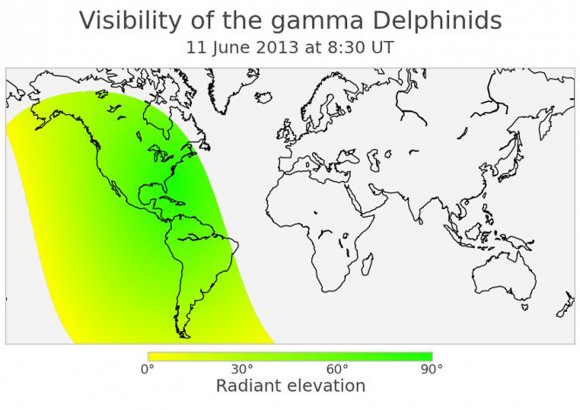

The Delta Aquarids are also one the very few showers with a southern hemisphere radiant. It’s somewhat of a mystery as to why meteor showers seem to favor the northern hemisphere. Of the 18 major annual meteor showers, only four occur below the ecliptic plane and three (the Alpha Capricornids, and the Eta and Delta Aquarids) approach the Earth from south of the equator. A statistical fluke, or just the product of the current epoch?

In fact, the Delta Aquarids have the most southern radiant of any major shower, with a radiant located just north of the bright star Fomalhaut in the constellation Piscis Austrinus near Right Ascension 339 degrees and Declination -17 degrees. Researchers have even broken this shower down into two distinct northern and southern radiants, although it’s the southern radiant that is the more active during the July season.

Together, this loose grouping of meteor shower radiants in the vicinity is known as the Aquarid-Capricornid complex. The Delta Aquarids are active from July 14th to August 18th, and unlike most showers, have a very broad peak. This is why you’ll see sites often quote the maximum for the shower at anywhere from July 28th to the 31st. In fact, you may just catch a stray Delta Aquarid while on vigil for the Perseids in a few weeks!

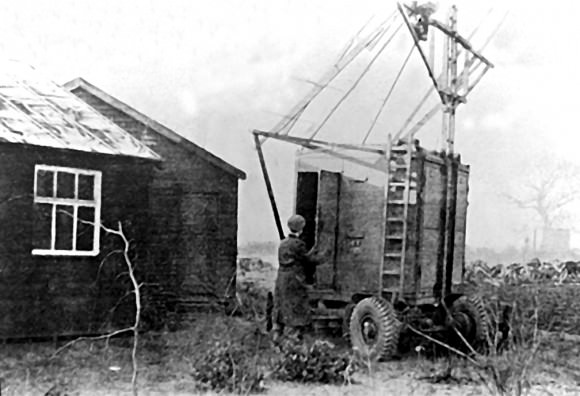

The shower was first identified by astronomer G.L. Tupman, who plotted 65 meteors associated with the stream in 1870. Observations of the Delta Aquarids were an off-and-on affair throughout the early 20th century, with many charts erroneously listing them as the “Beta Piscids”. The separate northern and southern radiants weren’t even untangled until 1950. The advent of radio astronomy made more refined observations of the Delta Aquarids possible. In 1949, Canadian astronomer D.W.R. McKinley based out of Ottawa, Canada identified both streams and pinned down the 41 km per second velocity that’s still quoted for the shower today.

Further radio studies of the shower were carried out at Jodrell Bank in the early 1950’s, and the shower gave strong returns in the early 1970’s for southern hemisphere observers even with the Moon above the horizon, with ZHRs approaching 40. The best return for the Southern Delta Aquarids in recent times is listed by the International Meteor Organization as a ZHR of about 40 on the morning of July 28th, 2009.

A study of the Delta Aquarids in 1963 by Fred Whipple and S.E. Hamid reveal striking similarities between the Delta Aquarids and the January Quadrantids & daytime Arietid stream active in June. They note that the orbital parameters of the streams were similar about 1,400 years ago, and the paths are thought to have diverged due to perturbations from the planet Jupiter.

Observing the Delta Aquarids can serve as a great “dry run” for the Perseids in a few weeks. You don’t need any specialized gear, simply find a dark site, block the Moon behind a building or hill, and watch.

Photographing meteors is similar to doing long exposures of star trails. Simply aim your tripod mounted DSLR camera at a section of sky and take a series of time exposures about 1-3 minutes long to reveal meteor streaks. Images of Delta Aquarids seem elusive, almost to the point of being mythical. An internet search turns up more blurry pictures of guys in ape suits purporting to be Bigfoot than Delta Aquarid images… perhaps we can document the “legendary Delta Aquarids” this year?

– Read more of the fascinating history of the Delta Aquarids here.

– Seen a meteor? Be sure to tweet it to #Meteorwatch.

– The IMO wants your meteor counts and observations!