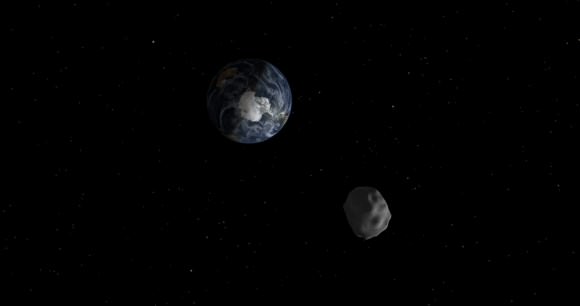

The Earth has always been bombarded with rocks from space. It’s true to say though that there were more rocks flying around the Solar System during earlier periods of its history. A team of researchers have been studying a meteorite impact from 3.26 billion years ago. They have calculated this rock was 200 times bigger than the one that wiped out the dinosaurs. The event would have triggered tsunamis mixing up the oceans and flushing debris from the land. The newly available organic material allowed organisms to thrive.

Continue reading “A Giant Meteorite Impact 3.26 Billion Years Ago Helped Push Life Forward”Explaining Different Kinds of Meteor Showers. It’s the Way the Comet Crumbles

The Universe often puts on a good show for us down here on Earth but one of the best spectacles must be a meteor shower. We see them when particles, usually the remains of comets, fall through our atmosphere and cause the atmosphere to glow. We see them as a fast moving streak of light but a new paper has suggested that the meteor showers we see can explain the sizes of the particles that originally formed the comet from where they came.

Continue reading “Explaining Different Kinds of Meteor Showers. It’s the Way the Comet Crumbles”Meteorites: Why study them? What can they teach us about finding life beyond Earth?

Universe Today has explored the importance of studying impact craters, planetary surfaces, exoplanets, astrobiology, solar physics, comets, planetary atmospheres, planetary geophysics, and cosmochemistry, and how this myriad of intricately linked scientific disciplines can assist us in better understanding our place in the cosmos and searching for life beyond Earth. Here, we will discuss the incredible research field of meteorites and how they help researchers better understand the history of both our solar system and the cosmos, including the benefits and challenges, finding life beyond Earth, and potential routes for upcoming students who wish to pursue studying meteorites. So, why is it so important to study meteorites?

Continue reading “Meteorites: Why study them? What can they teach us about finding life beyond Earth?”A Mars Meteorite Shows Evidence of a Massive Impact Billions of Years ago

Researchers at Australia’s Curtin University have discovered evidence of a massive impact on the Martian surface after 4.45 billion years ago. This may not seem like a surprising revelation – after all, we know that there were several large impacts on Mars, like Hellas and Argyre, and we know that large impacts happened frequently in the early solar system – so why is this a big deal?

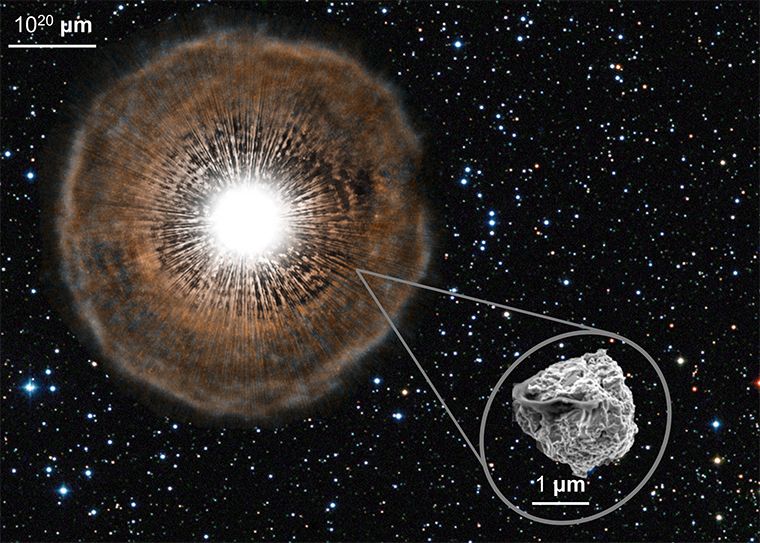

Continue reading “A Mars Meteorite Shows Evidence of a Massive Impact Billions of Years ago”Meteorites Found With Little Pieces of Other Stars

When Carl Sagan said, “We are all made of star stuff,” he didn’t just mean we were made up of parts of our own star. Other stars contributed to the material that built our solar system, and some of that “presolar” material is still present in a pristine form inside meteorites. Now, a team led by Dr. Nan Liu at Washington University in St. Louis took a close look at some of the parts of meteorites that formed before the Sun. They held some exciting surprises and answers.

Continue reading “Meteorites Found With Little Pieces of Other Stars”Almost 800,000 Years Ago, an Enormous Meteorite Struck Earth. Now We Know Where.

20% of the surface of Earth’s Eastern Hemisphere is littered with a certain kind of rock. Black, glossy blobs called tektites are spread throughout Australasia. Scientists know they’re from a meteorite strike, but they’ve never been able to locate the crater where it struck Earth.

Now a team of scientists seems to have found it.

Continue reading “Almost 800,000 Years Ago, an Enormous Meteorite Struck Earth. Now We Know Where.”Mars Curiosity Rolls Up to Potential New Meteorite

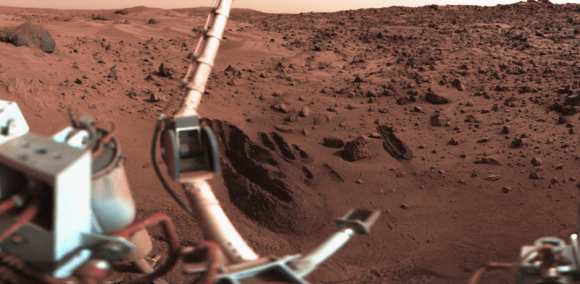

Rolling up the slopes of Mt. Sharp recently, NASA’s Curiosity rover appears to have stumbled across yet another meteorite, its third since touching down nearly four and a half years ago. While not yet confirmed, the turkey-shaped object has a gray, metallic luster and a lightly-dimpled texture that hints of regmaglypts. Regmaglypts, indentations that resemble thumbprints in Play-Doh, are commonly seen in meteorites and caused by softer materials stripped from the rock’s surface during the brief but intense heat and pressure of its plunge through the atmosphere.

Oddly, only one photo of the assumed meteorite shows up on the Mars raw image site. Curiosity snapped the image on Jan. 12 at 11:21 UT with its color mast camera. If you look closely at the photo a short distance above and to the right of the bright reflection a third of the way up from the bottom of the rock, you’ll spy three shiny spots in a row. Hmmm. Looks like it got zapped by Curiosity’s ChemCam laser. The rover fires a laser which vaporizes part of the meteorite’s surface while a spectrometer analyzes the resulting cloud of plasma to determine its composition. The mirror-like shimmer of the spots is further evidence that the gray lump is an iron-nickel meteorite.

Curiosity has driven more than 9.3 miles (15 km) since landing inside Mars’ Gale Crater in August 2012. It spent last summer and part of fall in a New Mexican-like landscape of scenic mesas and buttes called “Murray Buttes.” It’s since departed and continues to climb to sequentially higher and younger layers of the lower part of Mt. Sharp to investigate additional rocks. Scientists hope to create a timeline of how the region’s climate changed from an ancient freshwater lake environment with conditions favorable for microbial life (if such ever evolved) to today’s windswept, frigid desert.

Assuming the examination of the rock proves a metallic composition, this new rock would be the eighth discovered by our roving machines. All of them have been irons despite the fact that at least on Earth, iron meteorites are rather rare. About 95% of all found or seen-to-fall meteorites are the stony variety (mostly chondrites), 4.4% are irons and 1% stony-irons.

NASA’s Opportunity rover found five metal meteorites, and Curiosity’s rumbled by its first find, a honking hunk of metallic gorgeousness named Lebanon, in May 2014. If this were Earth, the new meteorite’s smooth, shiny texture would indicate a relatively recent fall, but who’s to say how long it’s been sitting on Mars. The planet’s not without erosion from wind and temperature changes, but it lacks the oxygen and water that would really eat into an iron-nickel specimen like this one. Still, the new find looks polished to my eye, possibly smoothed by wind-whipped sand grains during the countless Martian dust storms that have raged over the eons.

Why no large stony meteorites have yet to be been found on Mars is puzzling. They should be far more common; like irons, stonies would also display beautiful thumprinting and dark fusion crust to boot. Maybe they simply blend in too well with all the other rocks littering the Martian landscape. Or perhaps they erode more quickly on Mars than the metal variety.

Every time a meteorite turns up on Mars in images taken by the rovers, I get a kick out of how our planet and the Red One not only share water, ice and wind but also getting whacked by space rocks.

Why Does Siberia Get All the Cool Meteors?

Children ice skating in Khakassia, Russia react to the fall of a bright fireball two nights ago on Dec.6

In 1908 it was Tunguska event, a meteorite exploded in mid-air, flattening 770 square miles of forest. 39 years later in 1947, 70 tons of iron meteorites pummeled the Sikhote-Alin Mountains, leaving more than 30 craters. Then a day before Valentine’s Day in 2013, hundreds of dashcams recorded the fiery and explosive entry of the Chelyabinsk meteoroid, which created a shock wave strong enough to blow out thousands of glass windows and litter the snowy fields and lakes with countless fusion-crusted space rocks.

Documentary footage from 1947 of the Sikhote-Alin fall and how a team of scientists trekked into the wilderness to find the craters and meteorite fragments

Now on Dec. 6, another fireball blazed across Siberian skies, briefly illuminated the land like a sunny day before breaking apart with a boom over the town of Sayanogorsk. Given its brilliance and the explosions heard, there’s a fair chance that meteorites may have landed on the ground. Hopefully, a team will attempt a search soon. As long as it doesn’t snow too soon after a fall, black stones and the holes they make in snow are relatively easy to spot.

OK, maybe Siberia doesn’t get ALL the cool fireballs and meteorites, but it’s done well in the past century or so. Given the dimensions of the region — it covers 10% of the Earth’s surface and 57% of Russia — I suppose it’s inevitable that over so vast an area, regular fireball sightings and occasional monster meteorite falls would be the norm. For comparison, the United States covers only 1.9% of the Earth. So there’s at least a partial answer. Siberia’s just big.

Every day about 100 tons of meteoroids, which are fragments of dust and gravel from comets and asteroids, enter the Earth’s atmosphere. Much of it gets singed into fine dust, but the tougher stuff — mostly rocky, asteroid material — occasionally makes it to the ground as meteorites. Every day then our planet gains about a blue whale’s weight in cosmic debris. We’re practically swimming in the stuff!

Most of this mass is in the form of dust but a study done in 1996 and published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society further broke down that number. In the 10 gram (weight of a paperclip or stick of gum) to 1 kilogram (2.2 lbs) size range, 6,400 to 16,000 lbs. (2900-7300 kilograms) of meteorites strike the Earth each year. Yet because the Earth is so vast and largely uninhabited, appearances to the contrary, only about 10 are witnessed falls later recovered by enterprising hunters.

A couple more videos of the Dec. 6, 2016 fireball over Khakassia and Sayanogorsk, Russia

Meteorites fall in a pattern from smallest first to biggest last to form what astronomers call a strewnfield, an elongated stretch of ground several miles long shaped something like an almond. If you can identify the meteor’s ground track, the land over which it streaked, that’s where to start your search for potential meteorites.

Meteorites indeed fall everywhere and have for as long as Earth’s been rolling around the sun. So why couldn’t just one fall in my neighborhood or on the way to work? Maybe if I moved to Siberia …

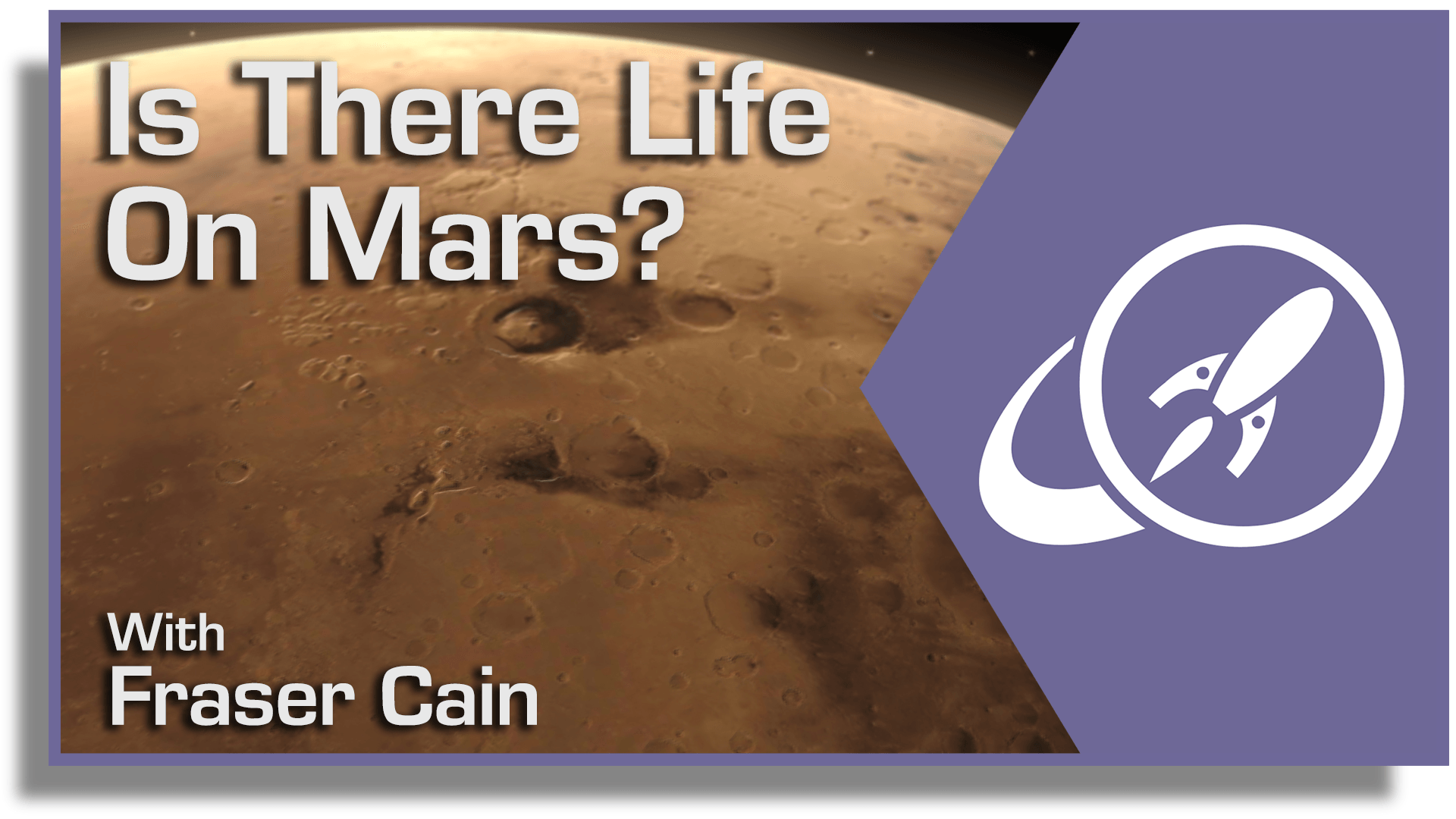

Is There Life on Mars?

Perhaps the most important question we can possible ask is, “are we alone in the Universe?”.

And so far, the answer has been, “I don’t know”. I mean, it’s a huge Universe, with hundreds of billions of stars in the Milky Way, and now we learn there are trillions of galaxies in the Universe.

Is there life closer to home? What about in the Solar System? There are a few existing places we could look for life close to home. Really any place in the Solar System where there’s liquid water. Wherever we find water on Earth, we find life, so it make sense to search for places with liquid water in the Solar System.

I know, I know, life could take all kinds of wonderful forms. Enlightened beings of pure energy, living among us right now. Or maybe space whales on Titan that swim through lakes of ammonia. Beep boop silicon robot lifeforms that calculate the wasted potential of our lives.

Sure, we could search for those things, and we will. Later. We haven’t even got this basic problem done yet. Earth water life? Check! Other water life? No idea.

It turns out, water’s everywhere in the Solar System. In comets and asteroids, on the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn, especially Europa or Enceladus. Or you could look for life on Mars.

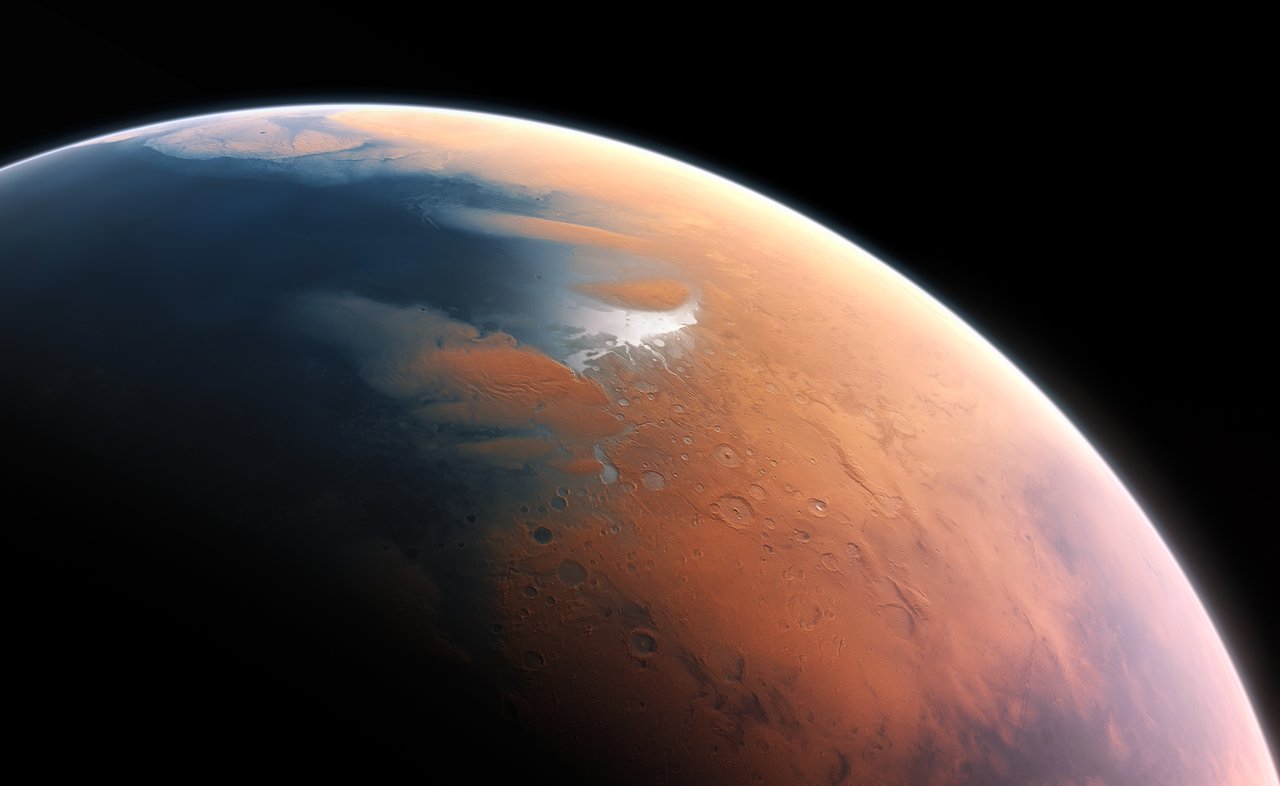

Mars is similar to Earth in many ways, however, it’s smaller, has less gravity, a thinner atmosphere. And unfortunately, it’s bone dry. There are vast polar caps of water ice, but they’re frozen solid. There appears to be briny liquid water underneath the surface, and it occasionally spurts out onto the surface. Because it’s close and relatively easy to explore, it’s been the place scientists have gone looking for past or current life.

Researchers tried to answer the question with NASA’s twin Viking Landers, which touched down in 1976. The landers were both equipped with three biology experiments. The researchers weren’t kidding around, they were going to nail this question: is there life on Mars?

In the first experiment, they took soil samples from Mars, mixed in a liquid solution with organic and inorganic compounds, and then measured what chemicals were released. In a second experiment, they put Earth organic compounds into Martian soil, and saw carbon dioxide released. In the third experiment, they heated Martian soil and saw organic material come out of the soil.

Three experiments, and stuff happened in all three. Stuff! Pretty exciting, right? Unfortunately, there were equally plausible non-biological explanations for each of the results. The astrobiology community wasn’t convinced, and they still fight in brutal cage matches to this day. It was ambitious, but inconclusive. The worst kind of conclusive.

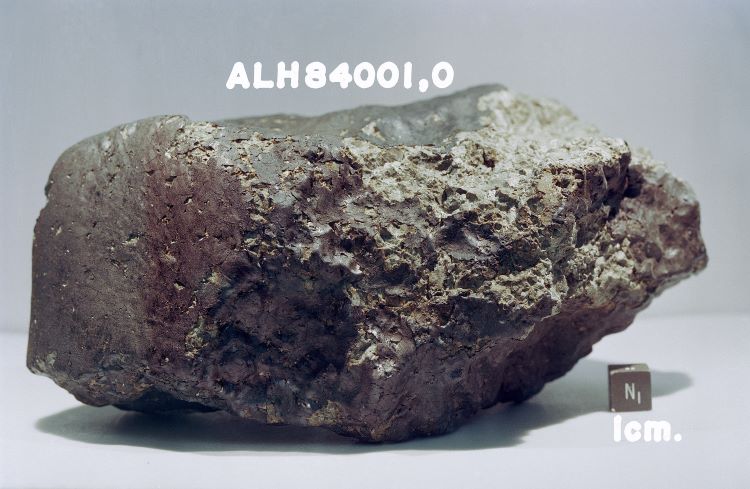

Researchers found more inconclusive evidence in 1994. Ugh, there’s that word again. They were studying a meteorite that fell in Antarctica, but came from Mars, based on gas samples taken from inside the rock.

They thought they found evidence of fossilized bacterial life inside the meteorite. But again, there were too many explanations for how the life could have gotten in there from here on Earth. Life found a way… to burrow into a rock from Mars.

NASA learned a powerful lesson from this experience. If they were going to prove life on Mars, they had to go about it carefully and conclusively, building up evidence that had no controversy.

The Spirit and Opportunity Rovers were an example of building up this case cautiously. They were sent to Mars in 2004 to find evidence of water. Not water today, but water in the ancient past. Old water Over the course of several years of exploration, both rovers turned up multiple lines of evidence there was water on the surface of Mars in the ancient past.

They found concretions, tiny pebbles containing iron-rich hematite that forms on Earth in water. They found the mineral gypsum; again, something that’s deposited by water on Earth.

NASA’s Curiosity Rover took this analysis to the next level, arriving in 2012 and searching for evidence that water was on Mars for vast periods of time; long enough for Martian life to evolve.

Once again, Curiosity found multiple lines of evidence that water acted on the surface of Mars. It found an ancient streambed near its landing site, and drilled into rock that showed the region was habitable for long periods of time.

In 2014, NASA turned the focus of its rovers from looking for evidence of water to searching for past evidence of life.

Curiosity found one of the most interesting targets: a strange strange rock formations while it was passing through an ancient riverbed on Mars. While it was examining the Gillespie Lake outcrop in Yellowknife Bay, it photographed sedimentary rock that looks very similar to deposits we see here on Earth. They’re caused by the fossilized mats of bacteria colonies that lived billions of years ago.

Not life today, but life when Mars was warmer and wetter. Still, fossilized life on Mars is better than no life at all. But there might still be life on Mars, right now, today. The best evidence is not on its surface, but in its atmosphere. Several spacecraft have detected trace amounts of methane in the Martian atmosphere.

Methane is a chemical that breaks down quickly in sunlight. If you farted on Mars, the methane from your farts would dissipate in a few hundred years. If spacecraft have detected this methane in the atmosphere, that means there’s some source replenishing those sneaky squeakers. It could be volcanic activity, but it might also be life. There could be microbes hanging on, in the last few places with liquid water, producing methane as a byproduct.

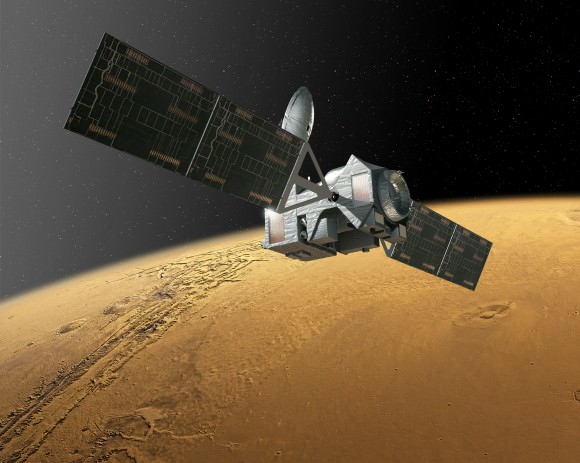

The European ExoMars orbiter just arrived at Mars, and its main job is sniff the Martian atmosphere and get to the bottom of this question.

Are there trace elements mixed in with the methane that means its volcanic in origin? Or did life create it? And if there’s life, where is it located? ExoMars should help us target a location for future study.

NASA is following up Curiosity with a twin rover designed to search for life. The Mars 2020 Rover will be a mobile astrobiology laboratory, capable of scooping up material from the surface of Mars and digesting it, scientifically speaking. It’ll search for the chemicals and structures produced by past life on Mars. It’ll also collect samples for a future sample return mission.

Even if we do discover if there’s life on Mars, it’s entirely possible that we and Martian life are actually related by a common ancestor, that split off billions of years ago. In fact, some astrobiologists think that Mars is a better place for life to have gotten started.

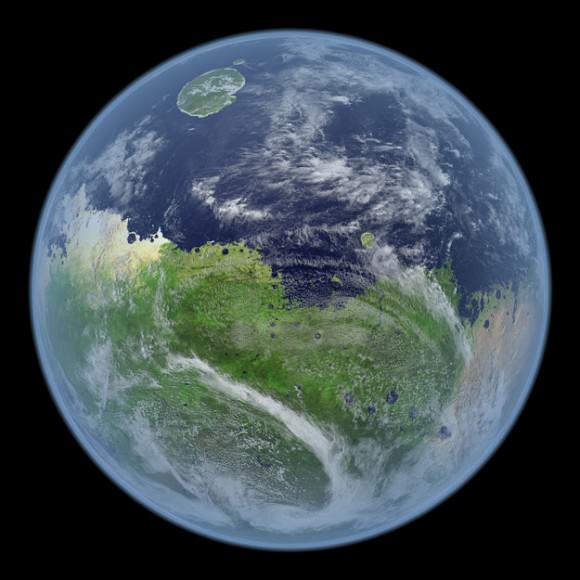

Not the dry husk of a Red Planet that we know today, but a much wetter, warmer version that we now know existed billions of years ago. When the surface of Mars was warm enough for liquid water to form oceans, lakes and rivers. And we now know it was like this for millions of years.

While Earth was still reeling from an early impact by the massive planet that crashed into it, forming the Moon, life on Mars could have gotten started early.

But how could we actually be related? The idea of Panspermia says that life could travel naturally from world to world in the Solar System, purely through the asteroid strikes that were regularly pounding everything in the early days.

Imagine an asteroid smashing into a world like Mars. In the lower gravity of Mars, debris from the impact could be launched into an escape trajectory, free to travel through the Solar System.

We know that bacteria can survive almost indefinitely, freeze dried, and protected from radiation within chunks of space rock. So it’s possible they could make the journey from Mars to Earth, crossing the orbit of our planet.

Even more amazingly, the meteorites that enter the Earth’s atmosphere would protect some of the bacterial inhabitants inside. As the Earth’s atmosphere is thick enough to slow down the descent of the space rocks, the tiny bacterialnauts could survive the entire journey from Mars, through space, to Earth.

If we do find life on Mars, how will we know it’s actually related to us? If Martian life has the similar DNA structure to Earth life, it’s probably related. In fact, we could probably trace the life back to determine the common ancestor, and even figure out when the tiny lifeforms make the journey.

If we do find life on Mars, which is related to us, that just means that life got around the Solar System. It doesn’t help us answer the bigger question about whether there’s life in the larger Universe. In fact, until we actually get a probe out to nearby stars, or receive signals from them, we might never know.

An even more amazing possibility is that it’s not related. That life on Mars arose completely independently. One clue that scientists will be looking for is the way the Martian life’s instructions are encoded. Here on Earth, all life follows “left-handed chirality” for the amino acid building blocks that make up DNA and RNA. But if right-handed amino acids are being used by Martian life, that would mean a completely independent origin of life.

Of course, if the life doesn’t use amino acids or DNA at all, then all bets are off. It’ll be truly alien, using a chemistry that we don’t understand at all.

There are many who believe that Mars isn’t the best place in the Solar System to search for life, that there are other places, like Europa or Enceladus, where there’s a vast amount of liquid water to be explored.

But Mars is close, it’s got a surface you can land on. We know there’s liquid water beneath the surface, and there was water there for a long time in the past. We’ve got the rovers, orbiters and landers on the planet and in the works to get to the bottom of this question. It’s an exciting time to be part of this search.

Monster Meteorite Found in Texas

On April 6, 2015, Frank Hommel was leading a group of guests at his Bar H Working Dude Ranch on a horseback ride. The horses got thirsty, so Hommel and crew rode cross-country in search of a watering hole. Along the way, his horse Samson suddenly stopped and refused to go any further. Ahead of them was a rock sticking out of the sandy soil. Hommel had never seen his horse act this way before, so he dismounted to get a closer look at the red, dimpled mass. Something inside told him this strange, out of place boulder had to be a meteorite.

Here’s the crazy thing — Hommel’s hunch was correct. Lots of people pick up an odd rock now and then they think might be a meteorite, but in nearly every case it isn’t. Meteorites are exceedingly rare, so you’re chances of happening across one are remote. But this time horse and man got it right.

The rock that stopped Samson that April day was the real deal and would soon be classified and named the Clarendon (c) stony meteorite. Only the top third of the mass broke the surface; there was a lot more beneath the soil. Hommel used a tractor to free the beast and tow it to his home. Later, when he and his wife DeeDee got it weighed on the feed store scale, the rock registered a whopping 760 pounds (345 kilograms). Hommel with others returned to the site and recovered an additional 70 pounds (32 kilograms) of loose fragments scattered about the area.

At this point, Frank and DeeDee couldn’t be certain it was a meteorite. Yes, it attracted a magnet, a good sign, but the attraction was weak. Frank had his doubts. To prove one way or another whether this rusty boulder came from space or belonged to the Earth, DeeDee sent a photo of it to Eric Twelker of Juneau, Alaska, a meteorite seller who maintains the Meteorite Market website. Twelker thought it looked promising and wrote back saying so. Six months later, the family sent him a sample which he arranged to have tested by Dr. Tony Irving at the University of Washington.

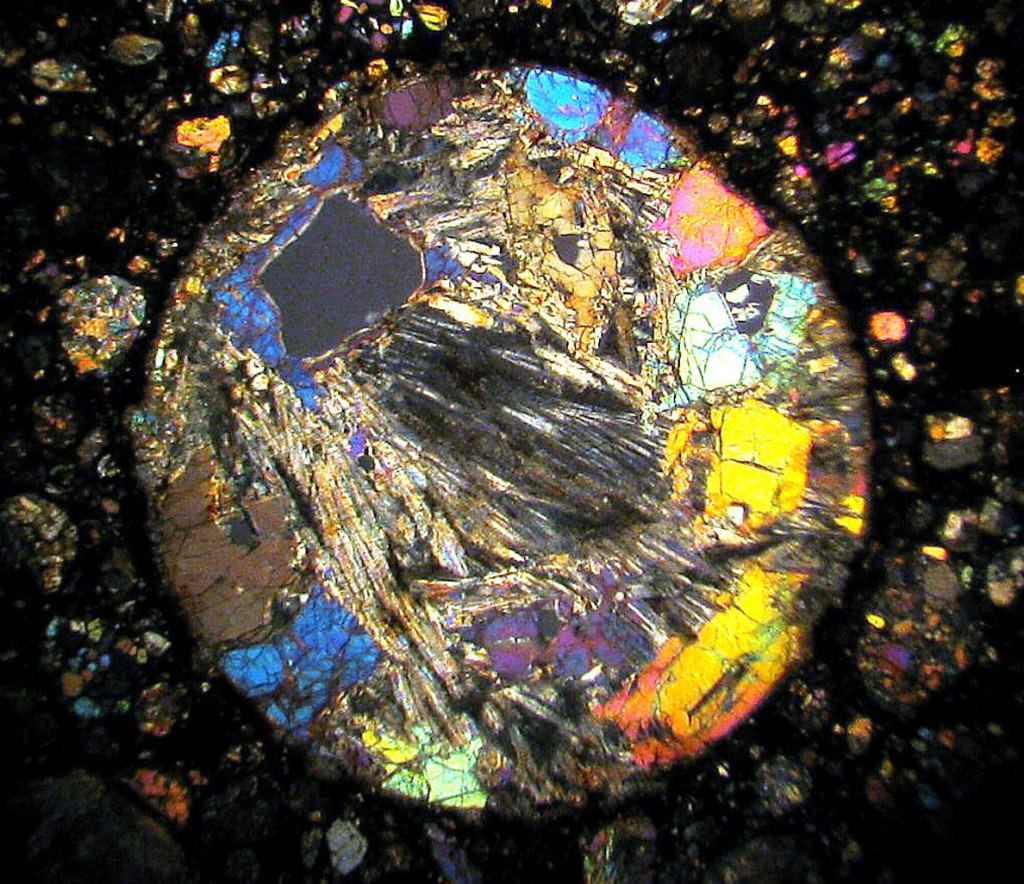

Irving’s analysis revealed bright grains of iron-nickel metal and an abundance of chondrules, round grains composed of minerals that were flash-heated into a “fiery rain” in the solar nebula 4.5 billion years ago. When they cooled, the melted material congealed into small solid spheres several millimeters across that were later incorporated into the planetary embryos that grew into today’s planets and asteroids. Finding iron-nickel and chondrules proved beyond a shadow that the Hommels’ rock was a genuine stone from space.

In an e-mail communication, Twelker recounted his part of the story:

“I get about six to a dozen inquiries on rocks every day. I try to answer all of them — and give a rock ID if possible. I have to say my patience gets tried sometimes after looking at slag, basalt, and limestone day after day. But if I am in the right mood, then it is fun. This one made it fun. Over the years, I’ve probably had a half dozen discoveries this way, but this is by far the most exciting.”

Irving pigeonholed it as an L4 chondrite meteorite. L stands for low-iron and chondrite indicates it still retains its ancient texture of chondrules that have been little altered since their formation. No one knows how long the meteorite has sat there, but the weathering of its surface would seem to indicate for a long time. That said, Hommel had been this way before and never noticed the rock. It’s possible that wind gradually removed the loosely-bound upper soil layer — a process called deflation — gradually exposing the meteorite to view over time.

Once a meteorite has been analyzed and classification, the information is published in the Meteorite Bulletin along with a chemical analysis and circumstances of its discovery. Meteorites are typically named after the nearest town or prominent geographical feature where they’re discovered or seen to fall. Because it was found on the outskirts of Clarendon, Texas, the Hommels’ meteorite took the town’s name. The little “c” in parentheses after the name indicates it’s the third unique meteorite found in the Clarendon area. Clarendon (b) turned up in 1981 and Clarendon (a) in 1979. Both are H5 (high metal) unrelated stony chondrites.

When Clarendon (c) showed up in the Bulletin late last month, meteorite hunter, dealer and collector Ruben Garcia, better known as Mr. Meteorite, quickly got wind of it. Garcia lives in Phoenix and since 1998 has made his livelihood buying and selling meteorites. He got into the business by first asking himself what would be the funnest thing he could do with his time. The answer was obvious: hunt meteorites!

These rusty rocks, chips off asteroids, have magical powers. Ask any meteorite collector. Touch one and you’ll be transported to a time before life was even a twinkle in evolution’s eye. Their ancientness holds clues to that deepest of questions — how did we get here? Scientists zap them with ion beams, cut them into translucent slices to study under the microscope and even dissolve them in acid in search of clues for how the planets formed.

Garcia contacted the Hommels and posed a simple question:

“Hey, you have a big meteorite on your property. Do you want to sell it?”

They did. So Mr. Meteorite put the word out and two days later Texas Christian University made an offer to buy it. After a price was agreed upon, Garcia began making plans to return to Clarendon soon, load up the massive missive from the asteroid belt on his trailer and truck it to the university where the new owner plans to put it on public display, a centerpiece for all to admire.

Visit the largest chondrite ever found in Texas

“How amazing to walk into a dude ranch and see a museum quality specimen,” said Garcia on his first impression of the stone. “I’ve never seen a meteorite this big outside of a museum or gem show.” Ruben joined Frank to collect a few additional fragments which he plans to put up for sale sometime soon.

So how does Clarendon (c) rank weigh-wise to other meteorite falls and finds? Digging through my hallowed copy of Monica Grady’s Catalogue of Meteorites, it’s clear that iron meteorites take the cake for record weights among all meteorites.

But when it comes to stony chondrites, Clarendon (c) is by far the largest individual space rock to come out of Texas. It also appears to be the second largest individual chondrite meteorite ever found in the United States. Only the Paragould meteorite, which exploded over Arkansas in 1930, dropped a larger individual — 820 pounds (371.9 kg) of pure meteorite goodness that’s on display at the Arkansas Center for Space and Planetary Sciences in Fayetteville. There’s truth to the saying that everything’s bigger in Texas.

Every meteorite has a story. Some are witnessed falls, while others fall unnoticed only to be discovered decades or centuries later. The Clarendon meteorite parent body spent billions of years in the asteroid belt before an impact broke off a fragment that millions of years later found its way to Earth. Did this chip off the old block bury itself in Texas soil 100 years ago, a thousand? No one can say for sure yet. But one April afternoon in 2015 they stopped a man and his horse dead in their tracks.

*** If you’d like tips on starting your own meteorite collection, check out my new book, Night Sky with the Naked Eye. It covers all the wonderful things you can see in the night sky without special equipment plus additional topics including meteorites. The book publishes on Nov. 8, but you can pre-order it right now at these online stores. Just click an icon to go to the site of your choice — Amazon, Barnes & Noble or Indiebound. It’s currently available at the first two outlets for a very nice discount: