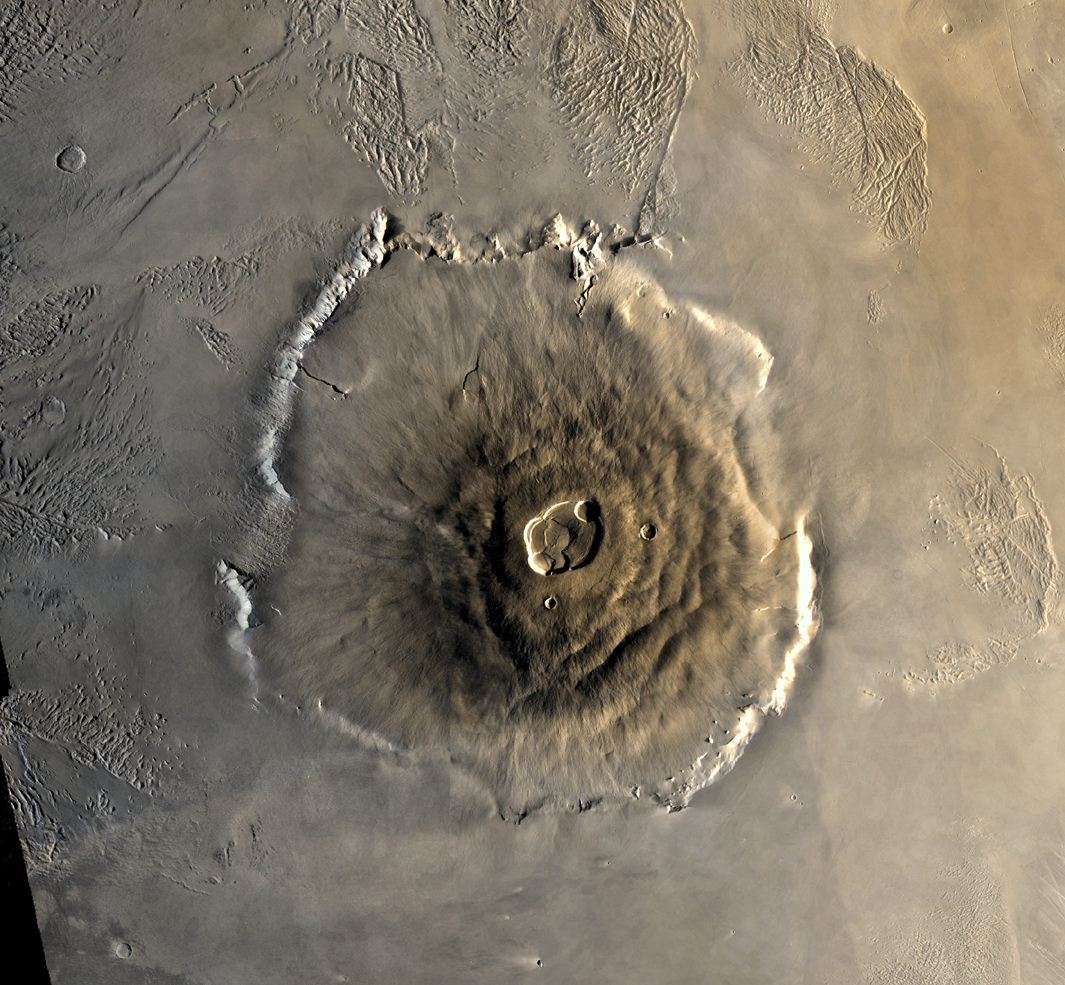

Mars is renowned for having the largest volcano in our Solar System, Olympus Mons. New research shows that Mars also has the most long-lived volcanoes. The study of a Martian meteorite confirms that volcanoes on Mars were active for 2 billion years or longer.

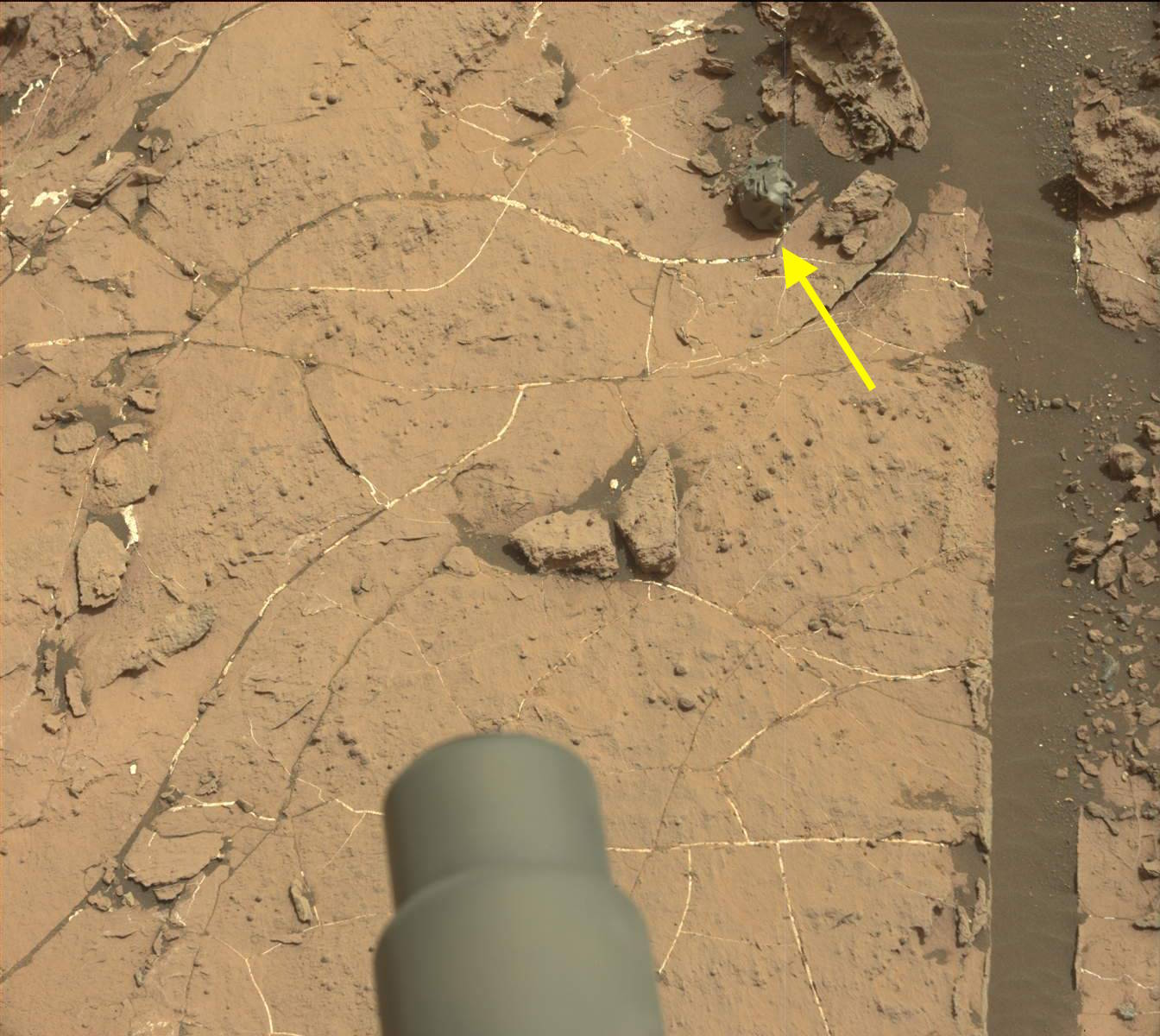

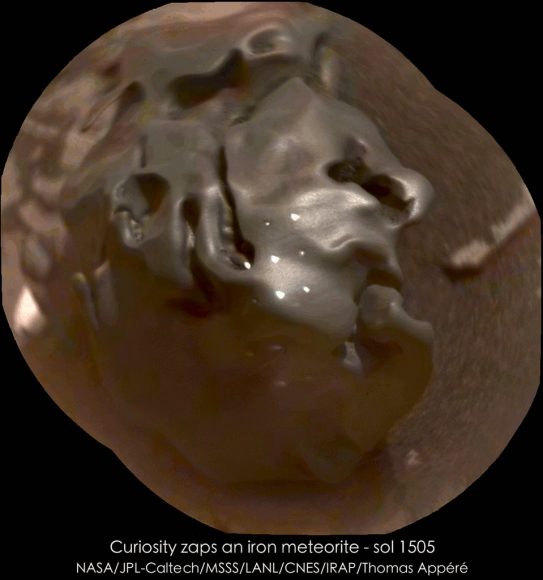

A lot of what we know about the volcanoes on Mars we’ve learned from Martian meteorites that have made it to Earth. The meteorite in this study was found in Algeria in 2012. Dubbed Northwest Africa 7635 (NWA 7635), this meteorite was actually seen travelling through Earth’s atmosphere in July 2011.

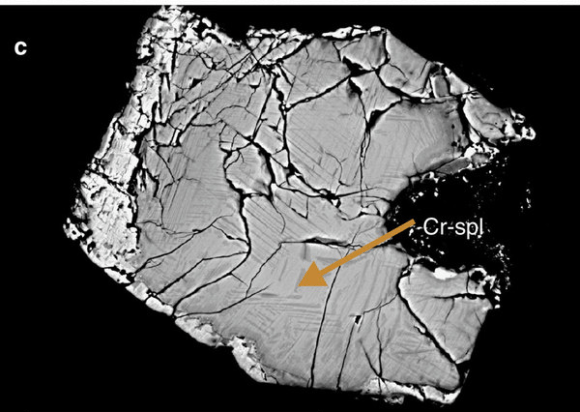

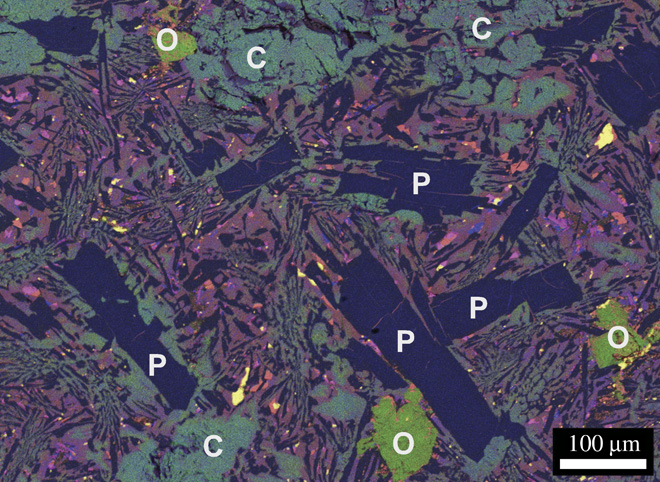

The lead author of this study is Tom Lapen, a Geology Professor at the University of Houston. He says that his findings provide new insights into the evolution of the Red Planet and the history of volcanic activity there. NWA 7635 was compared with 11 other Martian meteorites, of a type called shergottites. Analysis of their chemical composition reveals the length of time they spent in space, how long they’ve been on Earth, their age, and their volcanic source. All 12 of them are from the same volcanic source.

Mars has much weaker gravity than Earth, so when something large enough slams into the Martian surface, pieces of rock are ejected into space. Some of these rocks eventually cross Earth’s path and are captured by gravity. Most burn up, but some make it to the surface of our planet. In the case of NWA 7635 and the other meteorites, they were ejected from Mars about 1 million years ago.

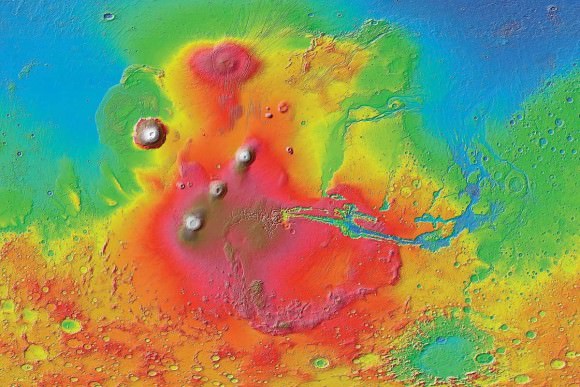

“We see that they came from a similar volcanic source,” Lapen said. “Given that they also have the same ejection time, we can conclude that these come from the same location on Mars.”

Taken together, the meteorites give us a snapshot of one location of the Martian surface. The other meteorites range from 327 million to 600 million years old. But NWA 7635 was formed 2.4 billion years ago. This means that its source was one of the longest lived volcanoes in our entire Solar System.

Volcanic activity on Mars is an important part of understanding the planet, and whether it ever harbored life. It’s possible that so-called super-volcanoes contributed to extinctions here on Earth. The same thing may have happened on Mars. Given the massive size of Olympus Mons, it could very well have been the Martian equivalent of a super-volcano.

The ESA’s Mars Express Orbiter sent back images of Olympus Mons that showed possible lava flows as recently as 2 million years ago. There are also lava flows on Mars that have a very small number of impact craters on them, indicating that they were formed recently. If that is the case, then it’s possible that Martian volcanoes will be visibly active again.

Continuing volcanic activity on Mars is highly speculative, with different researchers arguing for and against it. The relatively crater-free, smooth surfaces of some lava features on Mars could be explained by erosion, or even glaciation. In any case, if there is another eruption on Mars, we would have to be extremely lucky for one of our orbiters to see it.

But you never know.