Host: Fraser Cain

Astrojournalists: Morgan Rehnberg, David Dickinson, Elizabeth Howell, Jason Major, Casey Dreier, Mike Simmons

Continue reading “Weekly Space Hangout – February 28, 2014: Good NASA News and 715 Confirmed Planets!”

Where Did Earth’s Water Come From?

Anyone who’s ever seen a map or a globe easily knows that the surface of our planet is mostly covered by liquid water — about 71%, by most estimates* — and so it’s not surprising that all Earthly life as we know it depends, in some form or another, on water. (Our own bodies are composed of about 55-60% of the stuff.) But how did it get here in the first place? Based on current understanding of how the Solar System formed, primordial Earth couldn’t have developed with its own water supply; this close to the Sun there just wouldn’t have been enough water knocking about. Left to its own devices Earth should be a dry world, yet it’s not (thankfully for us and pretty much everything else living here.) So where did all the wet stuff come from?

As it turns out, Earth’s water probably wasn’t made, it was delivered. Check out the video above from MinuteEarth to learn more.

*71% of Earth’s surface, yes, but actually less total than you might think. Read more.

MinuteEarth (and MinutePhysics) is created by Henry Reich, with Alex Reich, Peter Reich, Emily Elert, and Ever Salazar. Music by Nathaniel Schroeder.

UPDATE March 2, 2014: recent studies support an “alien” origin of Earth’s water from meteorites, but perhaps much earlier in its formation rather than later. Read more from the Harvard Gazette here.

Experts Question Claim Tunguska Meteorite May Have Come from Mars

In 1908 a blazing white line cut across the sky before exploding a few miles above the ground with a force one thousand times stronger than the nuclear blast that leveled Hiroshima, Japan.

The resulting shock wave felled trees across more than 800 square miles in the remote forests of Tunguska, Siberia.

For over 100 years, the exact origins of the Tunguska event have remained a mystery. Without any fragments or impact craters to study, astronomers have been left in the dark. That’s not to say that all kinds of extraordinary causes haven’t been invoked to explain the event. Various people have thought of everything from Earth colliding with a small black hole to the crash of a UFO.

Russian researchers claim they may finally have evidence that will dislodge all conspiracy theories, but that “may” is huge. A team of four believes they have recovered fragments of the object — the so-called Tunguska meteorite — and even think they are Martian in origin. The research, however, is being called into question.

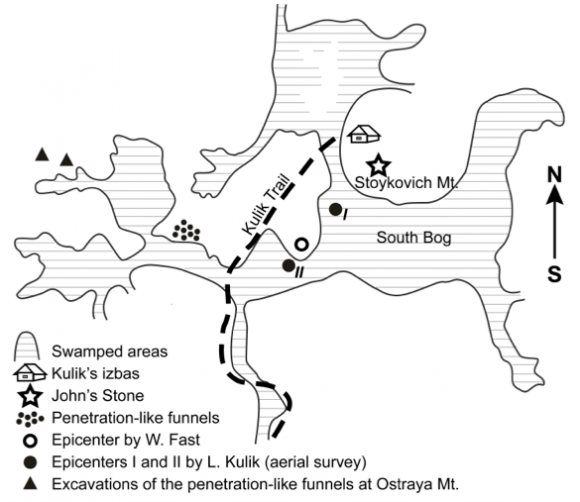

In a detective-like manner, the team surveyed 100 years’ worth of research. The researchers read eyewitness reports and analyzed aerial photos of the location. They performed a systematic survey of the central region in the felled forest and analyzed exotic rocks and penetration funnels.

Previously, numerous expeditions failed to recover any fragments that could be attributed conclusively to the long-sought Tunguska meteorite. But then Andrei Zlobin, of the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Vernadsky State Geological Museum, discovered three stones with possible traces of melting. He published the results in April 2013.

Zlobin’s discovery paper was received with skepticism and Universe Today covered the news immediately. A curious question arose quickly: why did it take so long for Zlobin to analyze his samples? The expedition took place in 1988, but it took 20 years before the three Tunguska candidates were nominated and another five years before Zlobin finished the paper.

By Zlobin’s admission, his discovery paper was only a preliminary study. He claimed he didn’t carry out a detailed chemical analysis of the rocks, which is necessary in order to reveal their true nature. Most field experts quickly dismissed the paper, feeling there was more work to be done before Zlobin could truly know if these rocks were fragments from the Tunguska meteor.

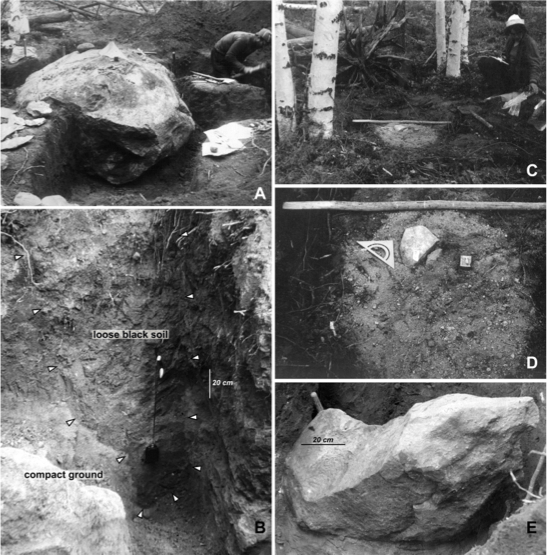

Today, new research is moving forward with an analysis of the rocks originally discovered by Zlobin. But an interesting new addition to the collection is a rock called “John’s Stone” — a large boulder discovered in July, 1972. While it’s mostly a dark gray now it was much lighter at the time of its discovery. “John’s Stone has an almond-like shape with one broken side,” lead author Dr. Yana Anfinogenov told Universe Today.

Now the skeptical reader might be asking the same question as before: why is there such a large time-lapse between the discovery of John’s Stone and the analysis presented here? (It’s interesting to note that while this elusive rock has been reviewed in the literature for over 40 years, this is the first time it has appeared in an English paper). Anfinogenov claimed that new data (especially concerning Martian geology) allowed for a much better analysis today than it did in recent years.

“The ground near John’s Stone presents undeniable impact signs suggesting that the boulder hit the ground with a catastrophic speed,” Anfinogenov told Universe Today. It left a deep trace in the permafrost which allowed researchers to note its trajectory and landing velocity coincides with that of the incoming Tunguska meteorite.

John’s Stone also contains shear-fractured splinter fragments with glossy coatings, indicating the strong effect of heat generated when it entered our atmosphere. The research team attempted to reproduce those glossy coatings found on the splinters by heating another fragment of John’s Stone to 500 degrees Celsius. The experiment was not successful as the fragment disintegrated in high heat.

“The authors do not present a strong case that the boulder known as John’s Stone was involved in the Tunguska event, or that it originated from Mars,” said Dr. Phil Bland, a meteorite expert at Curtin University in Perth, Australia.

They claim the mineral structure and chemical composition of the rocks — a quartz-sandstone with grain sizes of 0.5 to 1.5 cm and rich in silica — match rocks found on Mars. But their paper lacks any microanalysis of the samples, or isotopic study.

While there is a strong case that an impact on Mars could easily eject rock fragments that would then hit the Earth, something doesn’t match up. “The physics of ejecting material from Mars into interplanetary space argues for fragments with diameters of one to two meters, not the 20 to 30 meter range that would be required for Tunguska,” Bland told Universe Today.

It seems as though planetary geologists will require a much stronger case than this to be truly convinced John’s Stone is the Tunguska meteorite, let alone from Mars.

The paper is currently under peer-review but is available for download here.

Selling Rocks from Outer Space: an Interview with ‘Meteorite Man’ Geoff Notkin

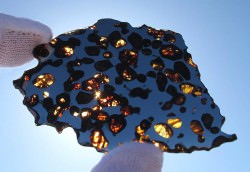

What’s the oldest thing you’ve ever held in your hand? A piece of petrified wood? A fossilized trilobite? A chunk of glacier-carved granite? Those are some pretty old things, sure, but there are even older objects to be found across the world… that came from out of this world. And thanks to “Meteorite Men” co-host, author, and educator Geoff Notkin and his company Aerolite Meteorites, you can own a truly ancient piece of the Solar System that can date back over 4.5 billion years.

Founded in 2005, Aerolite (which is an archaic term for meteorite) offers many different varieties of meteorites for sale, from gorgeous specimens worthy of a world-class museum to smaller fragments that you could proudly — and economically — display on your desk. Recently I had the opportunity to talk in depth with Geoff about Aerolite and his life’s work as a meteorite collector and dealer. Here are some of the fascinating things he had to say…

So Geoff, what initially got you interested in meteorites and finding them for yourself?

“It’s been a lifelong passion for me, but I’m lucky in that I can really put my finger on a specific event when I was a kid and that was my mother taking me to the Geological Museum in London when I was six or seven… I was already a rock hound, I loved collecting fossils, and my dad was a very keen amateur astronomer. And so I had this love of astronomy and this fascination with other worlds for as long as I can remember. I’m a very tactile person; I’m very hands-on. I like to know how things work… I want to know all the bits and pieces. I was frustrated a bit, because I wanted to know more about astronomy. I could see all these planets and places through the ‘scope, but I couldn’t touch them. But I could touch rocks and fossils.

“So I’m six or seven years old, and I’m on the second floor of the Museum in the Hall of Rocks and Minerals. And at the back was this small display area that’s very dark. And you walked through an arch, it’s almost like walking into a cave. And it was very low light back there, and that was the meteorite collection.

“There were a couple of large meteorites on stands, and in those days — it was the late 60s — security wasn’t the issue that it is today. So you could touch the big specimens, and so I put my hands on these giant meteorites and I was absolutely enthralled. And I had this sort of epiphany: meteorites were the locus between my two interests, astronomy and rock-hounding. Because they’re rocks… they’re rock samples from outer space. I promised myself as a kid that one day I would have an actual meteorite.

“By finding or owning meteorites, you are forging a solid and tangible connection with astronomy.”

“Of course at the time there was no meteorite business, no meteorite magazines, there was no network of collectors like there is today. Back in the late 60s when I gave myself this challenge it was like saying I was going to start my own space program! But not only did it come true, it’s become my career.”

What makes Aerolite such a great place to buy meteorites?

“I think the caring for the subject matter really shows on the website. We have the best photography in the entire meteorite industry. I think we have the largest selection… we certainly spend a great deal of time discussing the history and importance of pieces… every single meteorite on our website has a detailed description and in most cases multiple photographs. My view is if you’re going to do something, you should really do it to the best of your ability. We don’t cut any corners, we don’t sell anything unless we’re one hundred percent sure of what it is and where it came from.

“I want buyers and visitors to look at the website and share my sense of wonder about meteorites. I think meteorites are the most wonderful things in existence, they’re actual visitors from outer space — they’re inanimate aliens that have landed on our planet.”

“We do this because we want to share our passion. We stand by every piece that we sell.”

How can people be sure they are getting actual meteorites (and not just funny-looking rocks?)

“This is something that’s more important to pay attention to now than ever. Are there fakes, are there shady people? Yes and yes. If you go on eBay at any given time you will find numerous pieces that are being offered for sale that are either not meteorites at all or are one thing being passed off as another thing. Sometimes this is malicious, sometimes people just don’t know any better. So the best way to buy a meteorite and know that it’s real is to buy from a respected dealer who has a solid history in the field.

“I’m by no means the only person who does this. There are a number of very well-established dealers around the world, and a good place to start is the International Meteorite Collectors Association (of which Geoff is a member) which is an international group with hundreds of members — collectors and dealers… it’s sort of a watchdog group that tries to maintain high standards of integrity in the field.

“My company has a very strict policy of never offering anything that’s questionable.”

“I see fakes all the time,” Geoff added. “On eBay, on websites, in newspaper ads… you do have to be careful. My company has a very strict policy of never offering anything that’s questionable. And we do get offered questionable things. There are some countries that have strict policies about exporting meteorites — Australia and Canada being two of them — and we work very closely with academia in both countries, and we have legally exported meteorites from those countries. Not only do we abide by international regulations, we actively support them.”

So you not only offer meteorites for sale to the general public, but you also donate to schools and museums.

“We work very closely with most of the world’s major meteorite institutions. I have provided specimens to the American Museum of Natural History in New York, the British Museum of Natural History in London, the Vienna Museum of Natural History, the Center for Meteorite Studies… we work with almost everyone. When we find something that is new or different or exciting, we always donate a piece or pieces to our colleagues in academia. It’s just the right thing, it’s the right thing to do if you discover something important to make it available to science.

“Most universities and museums don’t have acquisitions budgets and can’t afford to buy things that they might like to have. In return they classify the meteorites that we found, and they go into the permanent literature and become more valuable as a result. A meteorite with a history and a name and classification is worth more than a random meteorite that somebody just found in a desert. So everybody benefits, it’s a really good match.”

In other words, you really are making a contribution to science as opposed to just “looting.”

“Exactly. And I have, a very few times, gotten emails from disgruntled viewers who didn’t understand what we were doing, saying ‘what makes you think it’s okay to come to Australia and take our meteorites,’ for example. So I wrote a very courteous email back saying that we were in Australia with the express permission and cooperation of the Australian park services and one of the senior park rangers was there with us. And not only did we follow the proper procedure in having those specimens exported from Australia, I donated rare meteorites to collections just as a ‘thank you’ for working with us. It wasn’t a trade, it was a thank you. So everywhere we go, whatever we do, we try and leave a good impression.”

Geoff added, “I do this out of love… this isn’t the best way to make a living! Being a meteorite hunter is probably not the best capital return on your time but it’s a very exciting and rewarding life in every other way.”

And thus, by buying meteorites from Aerolite, customers aren’t just helping pay for your expeditions and your work but also supporting research and education too.

“People who purchase from us are really participating in the growth of this science. Also, something very near and dear to my heart is science education for kids. You know that I am the host of an educational series called STEM Journals, which is a very — I think — amusing, entertaining, funny, fast-paced look at science, technology, engineering, and math topics. But you can’t make a living doing television shows like that. This is a labor of love… we do it because we think it’s important. If I didn’t have a commercial meteorite company to help underwrite the costs of educational programming and educational books, we just couldn’t do it. It’s as simple as that.

“So we always try to give back. That’s why I speak at schools and universities and give away meteorites to deserving kids at gem shows… because it was done to me when I was seven years old. The look of wonder you see on a kid’s face when you connect with them and they start to grasp the wonder of science… that’s something they’ll never forget.”

That’s great. And it sounds like you haven’t forgotten it yet either!

“I must say after all these years, I’ve been doing this close to full time for nearly twenty years and you never lose the amazement and the wonder of when a meteorite’s found or uncovered. I never go ‘oh, jeez, it’s just another billion-year-old space rock that fell to Earth!’ So it is a privilege to be in a work field where almost daily something wondrous happens.”

As we here at Universe Today know, when it concerns space that’s a common occurrence!

“Exactly!”

One last thing Geoff… do you think we’ll ever run out of meteorites?

“The meteorite collecting field has grown tremendously in the past ten years, and Meteorite Men is part of that. There is a finite supply of meteorites. Of course there are more landing all the time, but not enough to replenish the demand. Periodically there is a new very large discovery made, such as the Gebil Kamil iron in Egypt a couple of years ago. But what is happening is a significant increase in price and a decrease in selection, so some of the real staples we used to see… you can’t get them anymore.

“Still, people who want a meteorite collection, now is a great time for them to be buying because there are more meteorites available than in the past — but it’s not going to stay that way for very long. It’s like any other collectible that has a finite supply.”

Makes sense… I’ll take that as ‘inside advice’ to place an order soon!

______________

My thanks to Geoff for the chance to talk with him a little bit about his fascinating past, his passion, and his company. And as an added bonus to Universe Today readers, Geoff is extending a special 15% off on orders from Aerolite Meteorites — simply mention the code UNIVERSETODAY when you place an order!* (Trust me — once you browse through the site you’ll find something you want.) Also, if you’re in the Tucson area, Geoff Notkin and Aerolite Meteorites will have a table at the Tucson Gem and Mineral Show starting Jan. 31.

Be sure to check out Geoff’s television show STEM Journals on COX7 — the full first two seasons can be found online here and here, and shooting for the third season will be underway soon.

Want to know how to find “inanimate aliens” for yourself? You can find Geoff’s books on meteorite hunting here, as well as some of the right equipment for the job.

And don’t forget to follow Aerolite Meteorites and Geoff Notkin on Twitter!

*Sorry, the code isn’t valid for items already on sale or for select consignment items.

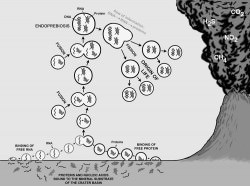

Catastrophic Impacts Made Life on Earth Possible

How did life on Earth originally develop from random organic compounds into living, evolving cells? It may have relied on impacts by enormous meteorites and comets — the same sort of catastrophic events that helped bring an end to the dinosaurs’ reign 65 million years ago. In fact, ancient impact craters might be precisely where life was able to develop on an otherwise hostile primordial Earth.

This is the hypothesis proposed by Sankar Chaterjee, Horn Professor of Geosciences and the curator of paleontology at the Museum of Texas Tech University.

“This is bigger than finding any dinosaur. This is what we’ve all searched for – the Holy Grail of science,” Chatterjee said.

Our planet wasn’t always the life-friendly “blue marble” that we know and love today. At one point early in its history it was anything but hospitable to life as we know it.

“When the Earth formed some 4.5 billion years ago, it was a sterile planet inhospitable to living organisms,” Chatterjee said. “It was a seething cauldron of erupting volcanoes, raining meteors and hot, noxious gasses. One billion years later, it was a placid, watery planet teeming with microbial life – the ancestors to all living things.”

Exactly how did this transition happen? That’s the Big Question in paleontology, and Chatterjee believes he may have found the answer lying within some of the world’s oldest and largest impact craters.

After studying the environments of the oldest known fossil-containing rocks in Greenland, Australia and South Africa, Chatterjee said these could be remnants of ancient craters and may be the very spots where life began in deep, dark and hot environments — similar to what’s found near thermal vents in today’s oceans.

Larger meteorites that created impact basins of about 350 miles in diameter inadvertently became the perfect crucibles, according to Chatterjee. These meteorites also punched through the Earth’s crust, creating volcanically driven geothermal vents. They also brought the basic building blocks of life that could be concentrated and polymerized in the crater basins.

In addition to new organic compounds — and, in the case of comets, considerable amounts of water — impacting bodies may also have brought the necessary lipids needed to help protect RNA and allow it to develop further.

“RNA molecules are very unstable. In vent environments, they would decompose quickly. Some catalysts, such as simple proteins, were necessary for primitive RNA to replicate and metabolize,” Chatterjee said. “Meteorites brought this fatty lipid material to early Earth.”

Based on research in Australia by University of California professor David Deamer, the ingredients for all-important cell membranes were delivered to Earth via meteorites and existed in water-filled craters.

“This fatty lipid material floated on top of the water surface of crater basins but moved to the bottom by convection currents,” suggests Chatterjee. “At some point in this process during the course of millions of years, this fatty membrane could have encapsulated simple RNA and proteins together like a soap bubble. The RNA and protein molecules begin interacting and communicating. Eventually RNA gave way to DNA – a much more stable compound – and with the development of the genetic code, the first cells divided.”

And the rest, as they say, is history. (Well, biology really, and no small amount of chemistry and paleontology… and some astrophysics… well you get the idea.)

Chatterjee recognizes that further experiments will be needed to help support or refute this hypothesis. He will present his findings Oct. 30 during the 125th Anniversary Annual Meeting of the Geological Society of America in Denver, Colorado.

Source: Texas Tech news article by John Davis

Student Science Thunders to Space from NASA Wallops

A Terrier-Improved Malemute suborbital rocket carrying experiments developed by university students nationwide in the RockSat-X program was successfully launched at 6 a.m. EDT August 13. Credit: NASA/Allison Stancil

Watch the cool Video below

[/caption]

WALLOPS ISLAND, VA – A nearly 900 pound complex payload integrated with dozens of science experiments created by talented university students in a wide range of disciplines and from all across America streaked to space from NASA’s beachside Wallops launch complex in Virginia on August 13 – just before the crack of dawn.

The RockSat-X science payload blasted off atop a Terrier-Improved Malemute suborbital sounding rocket at 6 a.m. from NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility along the Eastern Shore of Virginia.

As a research scientist myself it was thrilling to witness the thunderous liftoff standing alongside more than 40 budding aerospace students brimming with enthusiasm for the chance to participate in a real research program that shot to space like a speeding bullet.

“It’s a hands on, real world learning experience,” Chris Koehler told Universe Today at the Wallops launch pad. Koehler is Director of the Colorado Space Grant Consortium that manages the RockSat-X program in a joint educational partnership with NASA.

The hopes and dreams of everyone was flying along.

Here’s a cool NASA video of the RockSat-X Aug. 13 launch:

The students are responsible for conceiving, managing, assembling and testing the experiments, Koehler told me. Professors and industrial partners mentor and guide the students.

RockSat-X is the third of three practical STEM educational programs where the students master increasingly difficult skills that ultimately result in a series of sounding rocket launches.

“Not everything works as planned,” said Koehler. “And that’s by design. Some experiments fail but the students learn valuable lessons and apply them on the next flight.”

“The RockSat program started in 2008. And it’s getting bigger and growing in popularity every year,” Koehler explained.

The 2013 RockSat-X launch program included participants from seven universities, including the University of Colorado at Boulder; the University of Puerto Rico at San Juan; the University of Maryland, College Park; Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Md.; West Virginia University, Morgantown; University of Minnesota, Twin Cities; and Northwest Nazarene University, Nampa, Idaho.

We all watched as a group and counted down the final 10 seconds to blastoff just a few hundred yards (meters) away from the launch pad – Whooping and hollering as the first stage ignited with a thunderous roar. Then the second stage flash – and more yelling and screams of joy! – – listen to the video.

Moments later we saw the first stage plummeting and heard a loud thud as it crashed into the ocean just 10 miles or so offshore.

For most of the students -ranging from freshman to seniors – it was their first time seeing a rocket launch.

“I’m so excited to be here at NASA Wallops and see my teams experiment reach space!” said Hector, one of a dozen aerospace students who journeyed to Wallops from Puerto Rico.

Local Wallops area spectators and tourists told me they could hear the rocket booming from viewing sites more than 10 miles away.

Others who ‘overslept’ were awoken by the rocket thunder and houses shaking.

Suborbital rockets still make for big bangs!

The Puerto Rican students very cool experiment aimed at capturing meteorite particles in space using 6 cubes of aerogel that were extended out from the rocket as it descended back to Earth, said Oscar Resto, Science Instrument specialist and leader of the Puerto Rican team during an interview at the launch complex.

“Seeing this rocket launch was the best experience of my life,” Hector told me. “This was my first time visiting the mainland. I hope to come back again!”

Another team of 7 students from Northwest Nazarene University (NNU), Idaho aimed to investigate the durability of the world’s first physically flexible integrated chips.

“Our experiment tested the flexibility of integrated circuit chips in the cryogenic environment of space,” Prof Stephen Parke of NNU, Idaho, told Universe Today in an interview at the launch pad.

“The two year project is a collaboration with chipmaker American Semiconductor, Inc based in Boise, Idaho.”

“The chips were mechanically and electrically exercised, or moved, during the flight under the extremely cold conditions in space – of below Minus 50 C – to test whether they would survive,” Parke told me.

The 44 foot long, two stage rocket flew on a parabolic arc and a southeasterly trajectory. The 20 foot RockSat-X payload soared to an altitude of approximately 94 miles above the Atlantic Ocean.

Telemetry and science data was successfully transmitted and received from the rocket during the flight.

The payload then descended back to Earth, deployed a 24 foot wide parachute and splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean some 90 miles offshore from Wallops Flight Facility. Overall the mission lasted about 20 minutes.

A commercial fishing boat hauled in the payload and brought it back to Wallops about 7 hours later.

By 2 p.m. the RockSat-X payload was back onsite at the Wallops ‘Rocket Factory’.

And I was on-hand as the gleeful students began tearing it apart to disengage their individual experiments to begin a week’s long process of assessing the outcome, analyzing the data and evaluating what worked and what failed. See my photos.

Included among the dozens of custom built student experiments were HD cameras, investigations into crystal growth and ferro fluids in microgravity, measuring the electron density in the E region (90-120km), aerogel dust collection on an exposed telescoping arm from the rockets side, effects of radiation damage on various electrical components, determining the durability of flexible electronics in the cryogenic environment of space and creating a despun video of the flight.

Indeed we already know that not every experiment worked. But that’s the normal scientific method – ‘Build a little, fly a little’.

New students are already applying to the 2014 RockSat program. And some of these students will return next year with thoughtful upgrades and new ideas!

The launch was dedicated in memory of another extremely bright young student named Brad Mason, who tragically passed away two weeks ago. Brad was a beloved intern at NASA Wallops this summer and a friend. Brad’s name was inscribed on the side of the rocket. Read about Brad at the NASA Wallops website.

…………….

Learn more about Suborbital science, Cygnus, Antares, LADEE, MAVEN and Mars rovers and more at Ken’s upcoming presentations

Sep 5/6/16/17: LADEE Lunar & Antares/Cygnus ISS Rocket Launches from Virginia”; Rodeway Inn, Chincoteague, VA, 8 PM

Oct 3: “Curiosity, MAVEN and the Search for Life on Mars – (3-D)”, STAR Astronomy Club, Brookdale Community College & Monmouth Museum, Lincroft, NJ, 8 PM

Citizen Scientists Hunt for Impact Craters in Persia

Citizen scientists have discovered planets beyond our Solar System and established morphological classifications for thousands of galaxies (e.g., the Planet Hunters and Galaxy Zoo projects). At an upcoming meeting of planetary scientists, Hamed Pourkhorsandi from the University of Tehran will present his efforts to mobilize citizens to identify impact craters throughout Persia. Pourkhorsandi said he is recruiting volunteers to identify craters using Google Earth, while continuing to seek sightings of fireballs cited in ancient books and among rural folk. Discovering impact craters is an important endeavour, since it helps astronomers estimate how many asteroids of a particular size strike Earth over a given time (i.e., the impact frequency). Indeed, that is especially relevant in light of the recent meteor explosion over Russia this past February (see the UT article here), which hints at the potentially destructive nature of such occurrences.

Satellite images have facilitated the detection of impact sites such as the Kamil and Puka craters, which were identified by V. de Michele and D. Hamacher using Google Earth, respectively (see the UT article here). Pourkhorsandi noted that, “Free access to satellite images has led to the investigation of earth’s surface by specialists and nonspecialists, attempts that have led to the discovery of new impact craters around the globe. [Yet] few researches on this topic have been done in the Middle East.” Incidentally, citizens are likewise being recruited to classify craters and features on other bodies in the Solar System (e.g., the Moon Zoo project).

In his paper, Pourkhorsandi describes examples of two targets investigated thus far: “1. a circular structure with a diameter of 200 m (33°21’57”N 58°14’24”E). [However,] there is no sign of … meteoritic fragments in the region that are primary diagnostic indicators for small size impact craters.” The second target is tied to an old tale, and note that the Puka crater in Australia was identified by following-up on an old Aboriginal story. However, Pourkhorsandi states that a field study of the second target (28°24’52” N 60°34’44” E) revealed that the crater is not associated with an impactor from space.

“Beside these structures, field studies on other craters in Persia are in progress, the outcomes of which will be announced in the near future,” said Pourkhorsandi.

View Larger Map

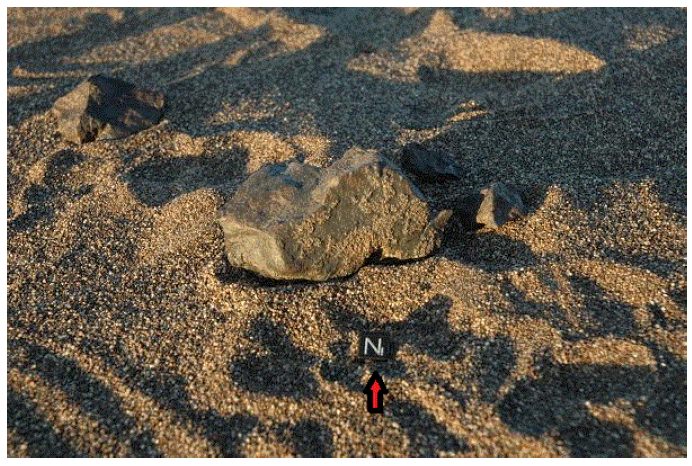

He went on to remark that, “Three recent short field trips to the central Lut desert led to the collection of several meteoritic fragments, which points to large concentrations of meteoritic materials in the area.” Some of those fragments are shown in the figure below, and the broader region is likely a pertinent place for citizen scientists to continue the hunt for impact craters in Persia.

Pourkhorsandi concluded by telling the Universe Today, “In the future we aim to expand our efforts with the help of additional people, and will direct individuals to scan other regions of the planet. Simultaneously, we have commenced a comprehensive analysis of meteorites in the Lut desert with fellow European scientists.”

H. Pourkhorsandi’s findings were shown at the 44th Lunar and Planetary conference in Texas, and will be presented at the upcoming Large Meteorite Impact and Evolution V conference. That latter conference will feature the latest results concerning the cratering process, and a description of the science program is available here. Copies of H. Pourkhorsandi and H. Mirnejad’s conference submissions are available via the LPI and arXiv. Those readers interested in joining H. Pourkhorsandi’s effort, or desiring additional information, may also find the following pertinent: the Earth Impact Database, Rampino and Haggerty 1996, “Collision Earth! The Threat from Outer Space” by P. Grego, NASA’s projects for Citizen Scientists.

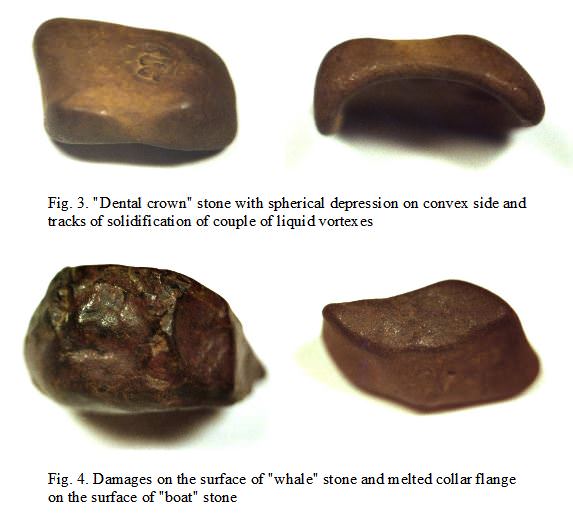

Possible Meteorite Fragments from 1908 Tunguska Explosion Found

The 1908 explosion over the Tunguska region in Siberia has always been an enigma. While the leading theories of what caused the mid-air explosion are that an asteroid or comet shattered in an airburst event, no reliable trace of such a body has ever been found. But a newly published paper reveals three different potential meteorite fragments found in the sandbars in a body of water in the area, the Khushmo River. While the fragments have all the earmarks of being meteorites from the event – which could potentially solve the 100-year old mystery — the only oddity is that the researcher actually found the fragments 25 years ago, and only recently has published his findings.

Like the recent Chelyabinsk airburst event, the Tunguska event likely also produced a shower of fragments from the exploding parent body, scientists have thought. But no convincing evidence has ever been found from the June 30, 1908 explosion that occurred over the Tunguska region. The explosion flattened trees in a 2,000 square kilometer area. Luckily, that region was largely uninhabited, but reportedly one person was killed and there were very few people that reported the explosion. Forensic-like research has determined the blast was 1,000 times more powerful than a nuclear bomb explosion, and it registered 5 on the Richter scale.

Previous expeditions to the region turned up empty as far as finding meteorites; however one expedition in 1939 by Russian mineralogist Leonid Kulik found a sample of melted glassy rock containing bubbles, which was considered evidence of an impact event. But the sample was somehow lost and has never undergone modern analysis.

The expedition in 1998 by Andrei Zlobin from the Russian Academy of Sciences was initially unsuccessful in finding meteorites or evidence of impacts. He made several drill holes in the peat bogs in the area and while he found evidence of the explosion, he didn’t find any meteorites. He then decided to look in the nearby river shoal.

Zlobin gathered about 100 samples of rocks that had features of potential meteorites, but further examination produced just three rocks with tell-tale features like melting and regmalypts – the , thumblike impressions found on the surface of meteorites which are caused by ablation as the hot rock falls through the atmosphere at high speed.

Zlobin writes that “After the expedition the author focused his efforts on experimental investigation of thermal processes and mathematical modeling of the Tunguska impact [Zlobin, 2007],” and he used tree ring evidence to estimate the temperatures from the event, and concluded that rocks already on the ground would not have been changed or melted from the blast, and therefore any rocks having evidence of melting should be from the impactor itself.

Zlobin says he has not yet carried out a detailed chemical analysis of the rocks, which would reveal their chemical and isotopic composition. But he does say the stony fragments do not rule out a comet since the nucleus could easily contain rock fragments. However, he has calculated the density of the impactor must have been about 0.6 grams per cubic centimeter, which is about the same as nucleus of Halley’s comet. Zlobin says that initially, the evidence seems “excellent confirmation of cometary origin of the Tunguska impact.”

While there is nothing definitive yet from Zlobin’s new paper – and there is the question of why he waited so long to conduct his study – his work provides hope for a better explanation of the Tunguska event as opposed to some rather off-the-wall ideas that have been proposed, such as a Tesla death-ray or an explosion of methane gas from the bogs.

The Technology Review blog writes that “clearly there is more work to be done here, particularly the chemical analysis perhaps with international cooperation and corroboration.”

Read Zlobin’s paper, Discovery of probably Tunguska meteorites at the bottom of Khushmo river’s shoal

Source: MIT Technology Review

Weekly Space Hangout – April 26, 2013

We had an action packed Weekly Space Hangout on Friday, with a vast collection of different stories in astronomy and spaceflight. This week’s panel included Alan Boyle, Dr. Nicole Gugliucci, Scott Lewis, Jason Major, and Dr. Matthew Francis. Hosted by Fraser Cain.

Some of the stories we covered included: Pulsar Provides Confirmation of General Relativity, Meteorites Crashing into Saturn’s Rings, Radio Observations of Betelgeuse, Progress Docks with the ISS, Hubble Observes Comet ISON, Grasshopper Jumps 250 Meters, April 25th Lunar Eclipse, and the Mars One Reality Show.

We record the Weekly Space Hangout every Friday at 12 pm Pacific / 3 pm Eastern. You can watch us live on Google+, Cosmoquest or listen after as part of the Astronomy Cast podcast feed (audio only).

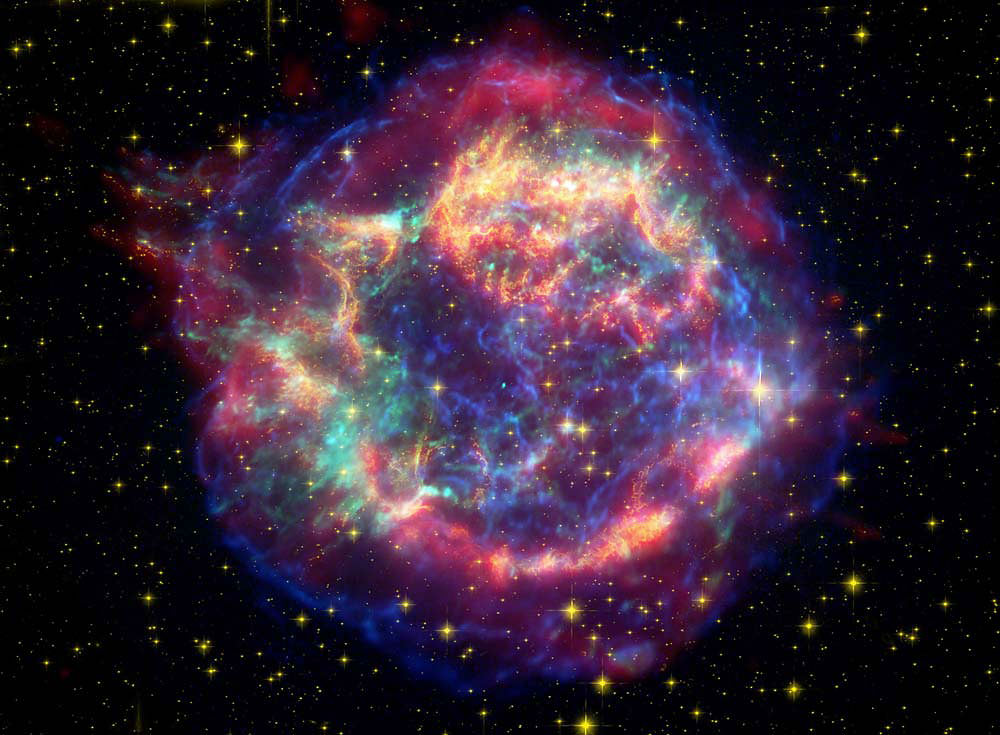

Cosmic C.S.I.: Searching for the Origins of the Solar System in Two Grains of Sand

“The total number of stars in the Universe is larger than all the grains of sand on all the beaches of the planet Earth,” Carl Sagan famously said in his iconic TV series Cosmos. But when two of those grains are made of a silicon-and-oxygen compound called silica, and they were found hiding deep inside ancient meteorites recovered from Antarctica, they very well may be from a star… possibly even the one whose explosive collapse sparked the formation of the Solar System itself.

Researchers from Washington University in St. Louis with support from the McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences have announced the discovery of two microscopic grains of silica in primitive meteorites originating from two different sources. This discovery is surprising because silica — one of the main components of sand on Earth today — is not one of the minerals thought to have formed within the Sun’s early circumstellar disk of material.

Instead, it’s thought that the two silica grains were created by a single supernova that seeded the early solar system with its cast-off material and helped set into motion the eventual formation of the planets.

According to a news release by Washington University, “it’s a bit like learning the secrets of the family that lived in your house in the 1800s by examining dust particles they left behind in cracks in the floorboards.”

Until the 1960s most scientists believed the early Solar System got so hot that presolar material could not have survived. But in 1987 scientists at the University of Chicago discovered miniscule diamonds in a primitive meteorite (ones that had not been heated and reworked). Since then they’ve found grains of more than ten other minerals in primitive meteorites.

The scientists can tell these grains came from ancient stars because they have highly unusual isotopic signatures, and different stars produce different proportions of isotopes.

But the material from which our Solar System was fashioned was mixed and homogenized before the planets formed. So all of the planets and the Sun have the pretty much the same “solar” isotopic composition.

Meteorites, most of which are pieces of asteroids, have the solar composition as well, but trapped deep within the primitive ones are pure samples of stars, and the isotopic compositions of these presolar grains can provide clues to their complex nuclear and convective processes.

Some models of stellar evolution predict that silica could condense in the cooler outer atmospheres of stars, but others say silicon would be completely consumed by the formation of magnesium- or iron-rich silicates, leaving none to form silica.

“We didn’t know which model was right and which was not, because the models had so many parameters,” said Pierre Haenecour, a graduate student in Earth and Planetary Sciences at Washington University and the first author on a paper to be published in the May 1 issue of Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Under the guidance of physics professor Dr. Christine Floss, who found some of the first silica grains in a meteorite in 2009, Haenecour investigated slices of a primitive meteorite brought back from Antarctica and located a single grain of silica out of 138 presolar grains. The grain he found was rich in oxygen-18, signifying its source as from a core-collapse supernova.

Finding that along with another oxygen-18-enriched silica grain identified within another meteorite by graduate student Xuchao Zhao, Haenecour and his team set about figuring out how such silica grains could form within the collapsing layers of a dying star. They found they could reproduce the oxygen-18 enrichment of the two grains through the mixing of small amounts of material from a star’s oxygen-rich inner zones and the oxygen-18-rich helium/carbon zone with large amounts of material from the outer hydrogen envelope of the supernova.

In fact, Haenecour said, the mixing that produced the composition of the two grains was so similar, the grains might well have come from the same supernova — possibly the very same one that sparked the collapse of the molecular cloud that formed our Solar System.

“It’s a bit like learning the secrets of the family that lived in your house in the 1800s by examining dust particles they left behind in cracks in the floorboards.”

Ancient meteorites, a few microscopic grains of stellar sand, and a lot of lab work… it’s an example of cosmic forensics at its best!