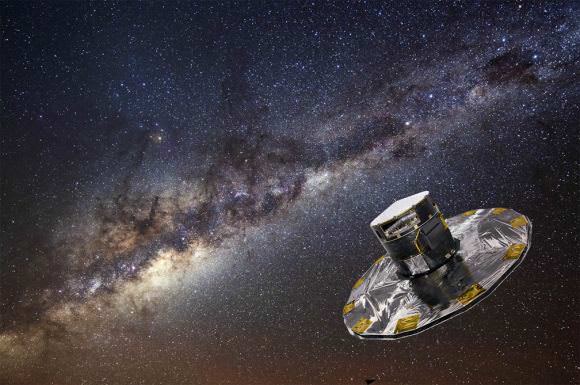

On December 19th, 2013, the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Gaia spacecraft took to space with one of the most ambitious missions ever. Over the course of its planned 5-year mission (which was recently extended), this space observatory would map over a billion stars, planets, comets, asteroids and quasars in order to create the largest and most precise 3D catalog of the Milky Way ever created.

The first release of Gaia data, which took place in September 2016, contained the distances and motions of over two million stars. But the second data release, which took place on April 25th, 2018, is even more impressive. Included in the release are the positions, distance indicators and motions of more than one billion stars, asteroids within our Solar System, and even stars beyond the Milky Way.

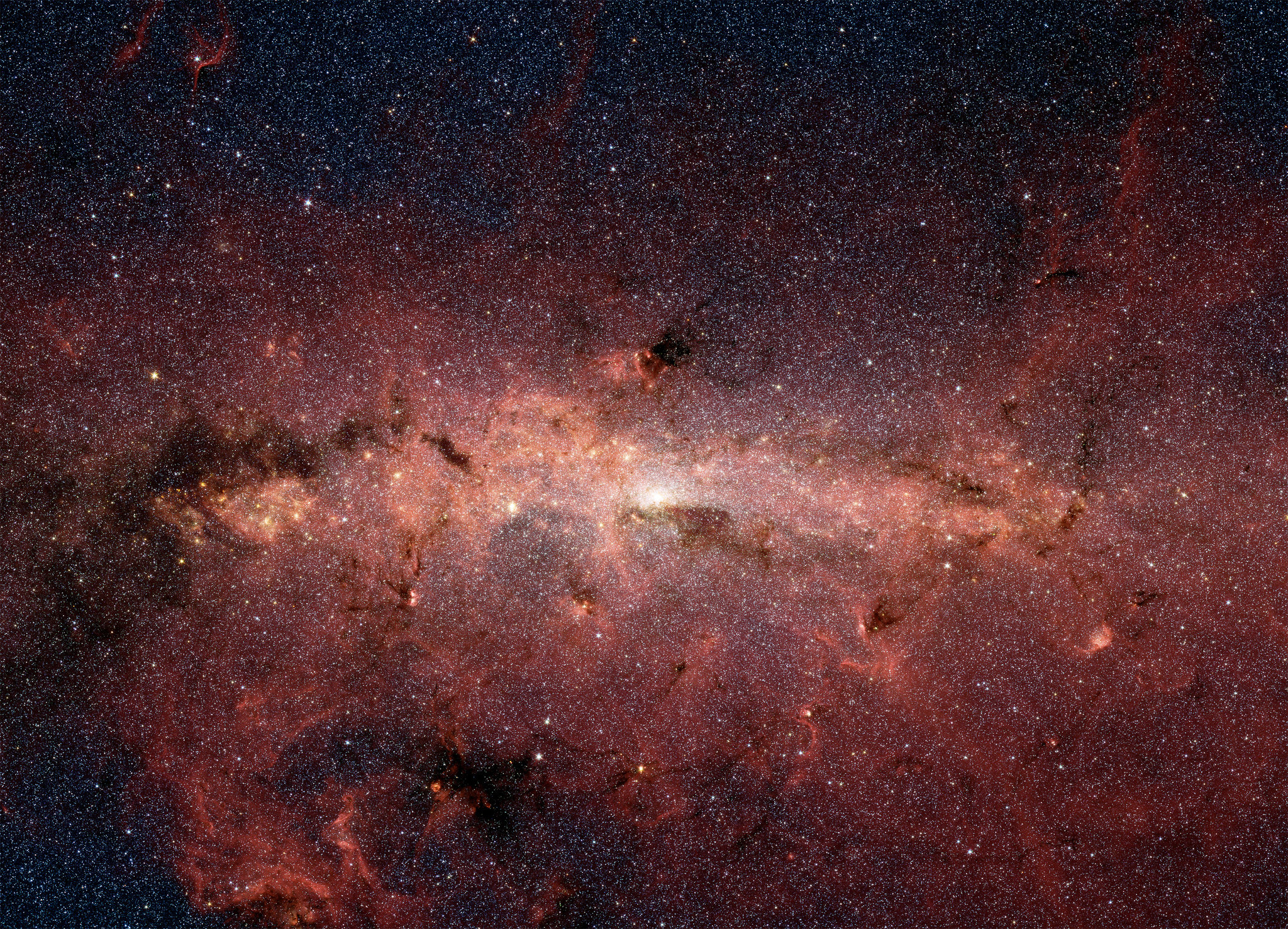

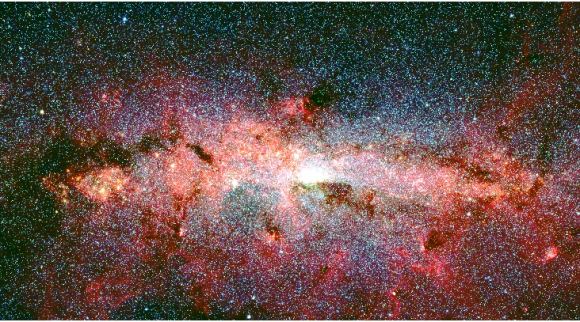

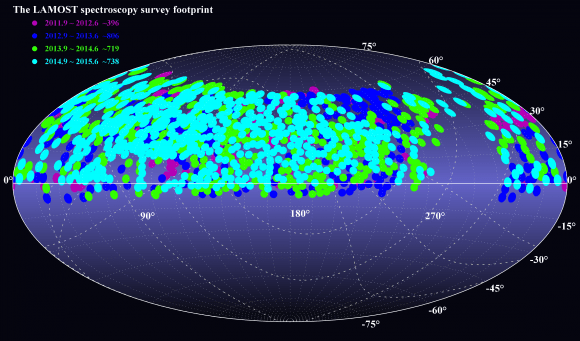

Whereas the first data release was based on just over a year’s worth of observations, the new data release covers a period of about 22 months – which ran from July 25th, 2014, to May 23rd, 2016. Preliminary analysis of this data has revealed fine details about 1.7 billion stars in the Milky Way and how they move, which is essential to understanding how our galaxy evolved over time.

As Günther Hasinger, the ESA Director of Science, explained in a recent ESA press release:

“The observations collected by Gaia are redefining the foundations of astronomy. Gaia is an ambitious mission that relies on a huge human collaboration to make sense of a large volume of highly complex data. It demonstrates the need for long-term projects to guarantee progress in space science and technology and to implement even more daring scientific missions of the coming decades.“

The precision of Gaia‘s instruments has allowed for measurements that are so accurate that it was possible to separate the parallax of stars – the apparent shift caused by the Earth’s orbit around the Sun – from their movements through the galaxy. Of the 1.7 billion stars cataloged, the parallax and velocity (aka. proper motion) of more than 1.3 billion were measured and listed.

For about 10% of these, the parallax measurements were so accurate that astronomers can directly estimate distances to the individual stars. As Anthony Brown of Leiden University, who is also the chair of the Gaia Data Processing and Analysis Consortium Executive Board, explained:

“The second Gaia data release represents a huge leap forward with respect to ESA‘s Hipparcos satellite, Gaia‘s predecessor and the first space mission for astrometry, which surveyed some 118 000 stars almost thirty years ago… The sheer number of stars alone, with their positions and motions, would make Gaia‘s new catalogue already quite astonishing. But there is more: this unique scientific catalogue includes many other data types, with information about the properties of the stars and other celestial objects, making this release truly exceptional.“

In addition to the proper motions of stars, the catalog provides information on a wide range of topics that will be of interest to astronomers and astrophysicists. These include brightness and color measurements of nearly all of the 1.7 billion stars cataloged, as well as information on how the brightness and color change for half a million variable stars over time.

It also contains the velocities along the line of sight of seven million stars, the surface temperatures of about 100 million, and the effect interstellar dust has on 87 million. The Gaia data also contains information on objects in our Solar System, which includes the positions of 14,000 known asteroids (which will allow for the precise determination of their orbits).

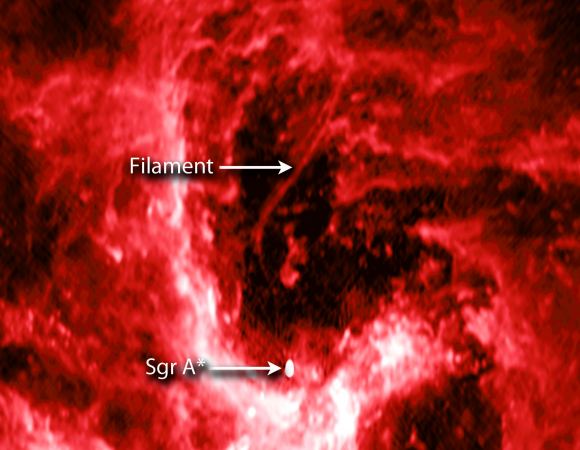

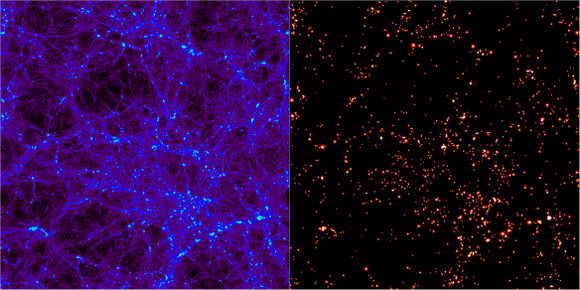

Beyond the Milky Way, Gaia obtained more accurate measurements of the positions of half a million distant quasars – bright galaxies that emit massive amounts of energy due to the presence of a supermassive black hole at their centers. In the past, quasars have been used as a reference frame for the celestial coordinates of all objects in the Gaia catalogue based on radio waves.

However, this information will now be available at optical wavelengths for the first time. This, and other developments made possible by Gaia, could revolutionize how we study our galaxy and the Universe. As Antonella Vallenari, from the Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica (INAF), the Astronomical Observatory of Padua, Italy, and the deputy chair of the Data Processing Consortium Executive Board, indicated:

“The new Gaia data are so powerful that exciting results are just jumping at us. For example, we have built the most detailed Hertzsprung-Russell diagram of stars ever made on the full sky and we can already spot some interesting trends. It feels like we are inaugurating a new era of Galactic archaeology.“

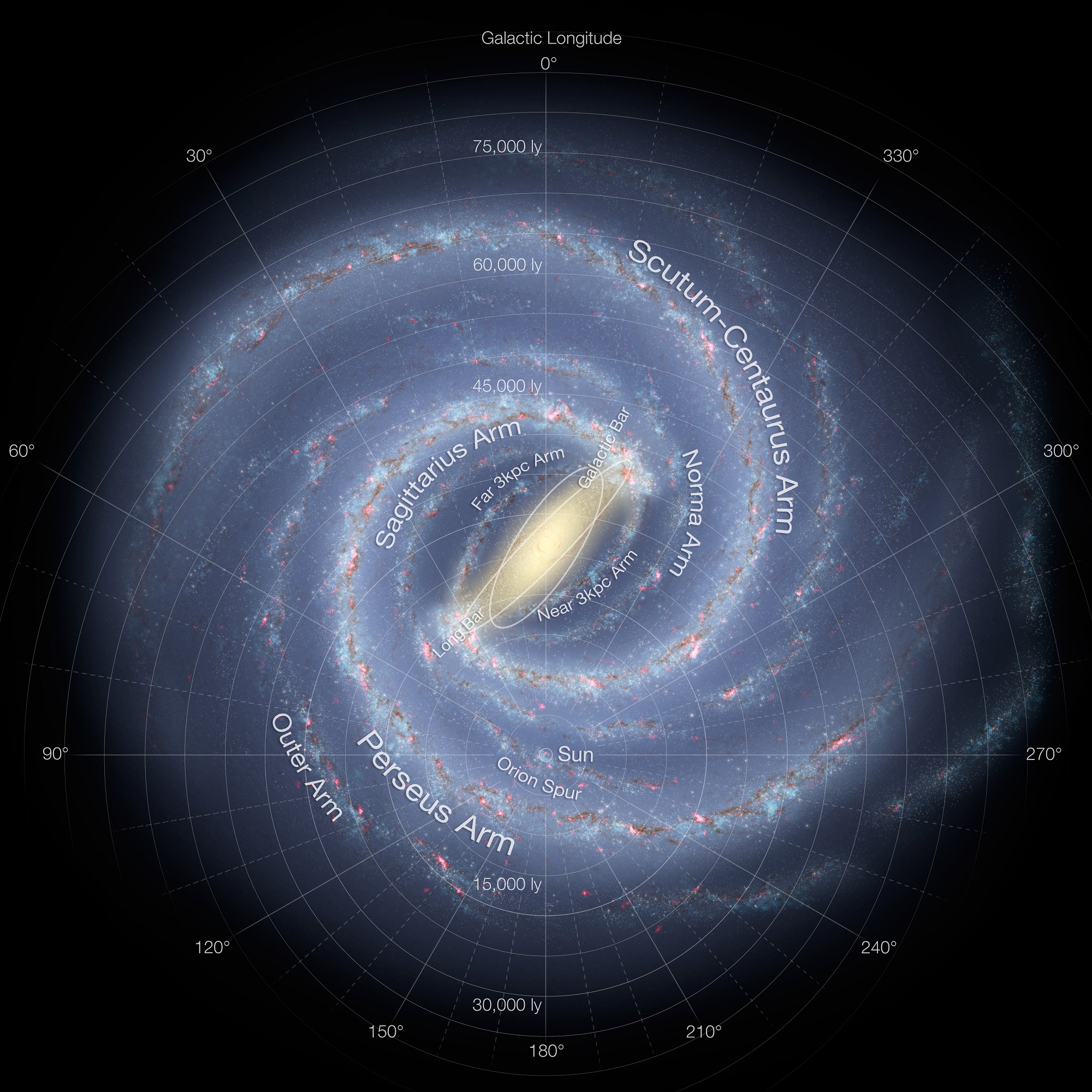

The Hertzsprung-Russell diagram, which is named after the two astronomers who devised it in the early 20th century, is fundamental to the study of stellar populations and their evolution. Based on four million stars that were selected from the catalog (all of which are withing five thousand light-years from the Sun), scientist were able to reveal many fine details about stars beyond our Solar System for the first time.

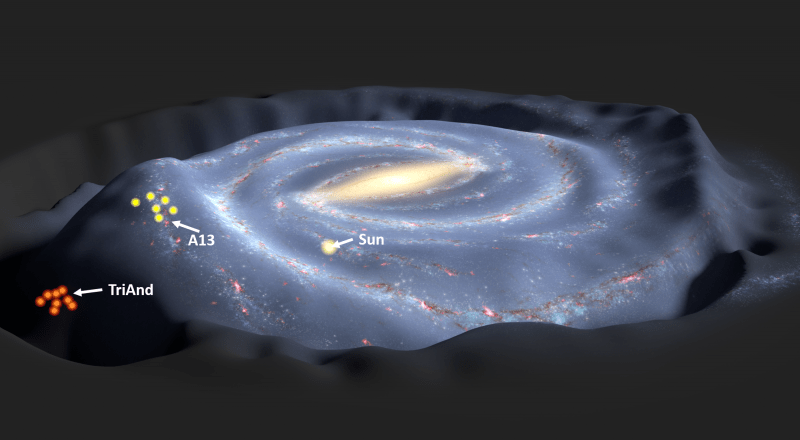

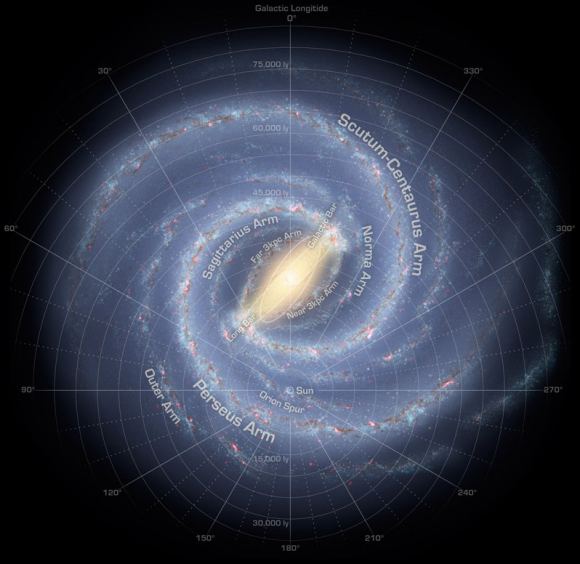

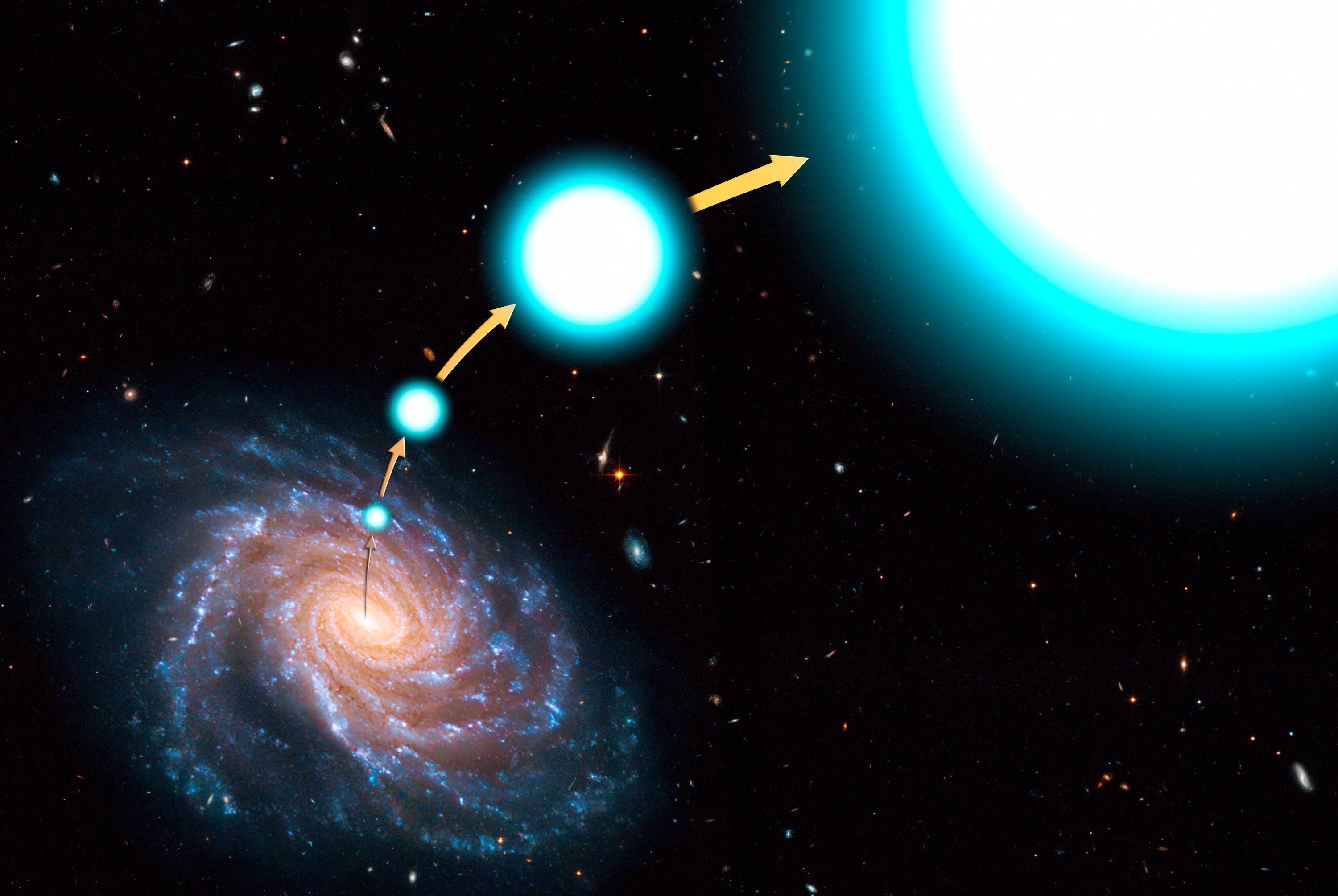

Along with measurements of their velocities, the Gaia Hertzsprung-Russell diagram enables astronomers to distinguish between populations of stars that are of different ages, are located in different regions of the Milky Way (i.e. the disk and the halo), and that formed in different ways. These include fast moving stars that were previously thought to belong to the halo, but are actually part of two stellar populations.

“Gaia will greatly advance our understanding of the Universe on all cosmic scales,” said Timo Prusti, a Gaia project scientist at ESA. “Even in the neighborhood of the Sun, which is the region we thought we understood best, Gaia is revealing new and exciting features.”

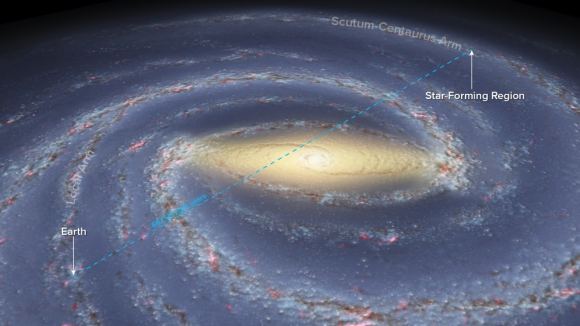

For instance, for a subset of stars within a few thousand light-years of the Sun, Gaia measured their velocity in all three dimensions. From this, it has been determined that they follow a similar pattern to stars that are orbiting the galaxy at similar speeds. The cause of these patterns will be the subject of future research, as it is unclear whether its caused by our galaxy itself or are the result of interactions with smaller galaxies that merged with us in the past.

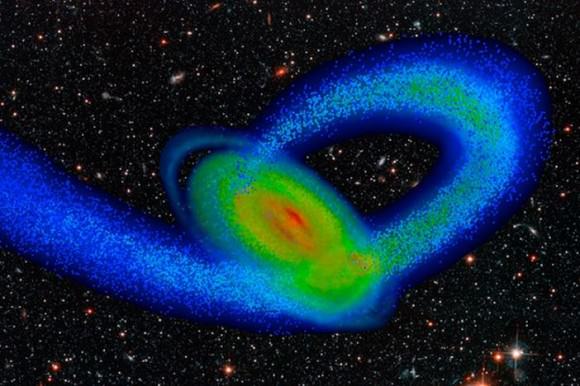

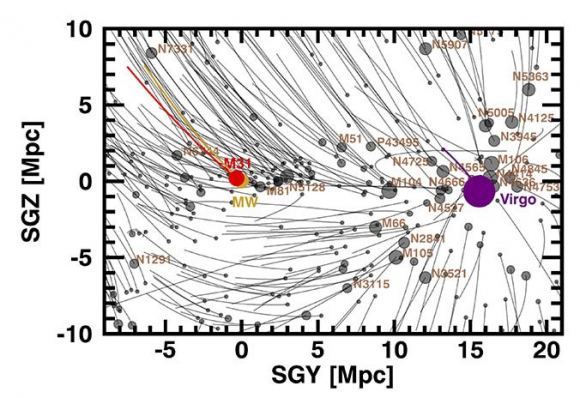

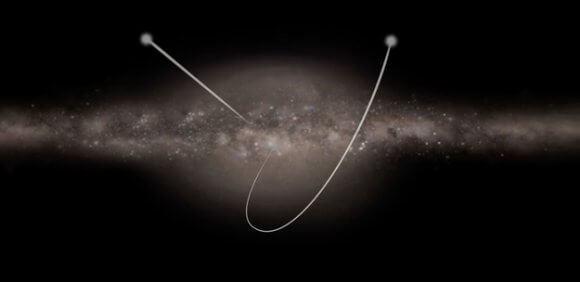

Last, but not least, Gaia data will be used to learn more about the orbits of 75 globular clusters and 12 dwarf galaxies that revolve around the Milky Way. This information will shed further light on the evolution of our galaxy, the gravitational forces affecting it, and the role played by dark matter. As Fred Jansen, the Gaia mission manager at ESA, put it:

“Gaia is astronomy at its finest. Scientists will be busy with this data for many years, and we are ready to be surprised by the avalanche of discoveries that will unlock the secrets of our Galaxy.“

The third release of Gaia data is scheduled to take place in late 2020, with the final catalog being published in the 2020s. Meanwhile, an extension has already been approved for the Gaia mission, which will now remain in operation until the end of 2020 (to be confirmed at the end of this year). A series of scientific papers describing what has been learned from this latest release will also appear in a special issue of Astronomy & Astrophysics.

From the evolution of stars to the evolution of our galaxy, the second Gaia data release is already proving to be a boon for astronomers and astrophysicists. Even after the mission concludes, we can expect scientists will still be analyzing the data and learning a great deal more about the structure and evolution of our Universe.

Further Reading: ESA