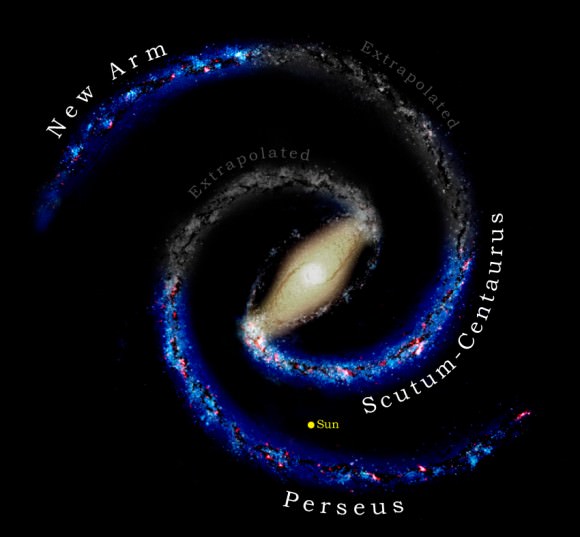

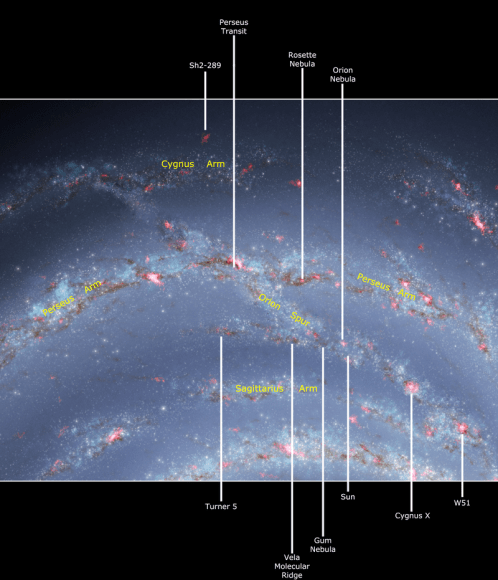

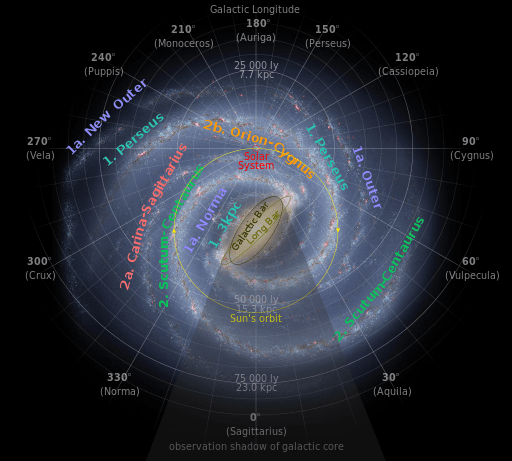

Want to hear something cool? There’s a black hole at the center of the Milky Way. And not just any black hole, it’s a supermassive black hole with more than 4.1 million times the mass of the Sun.

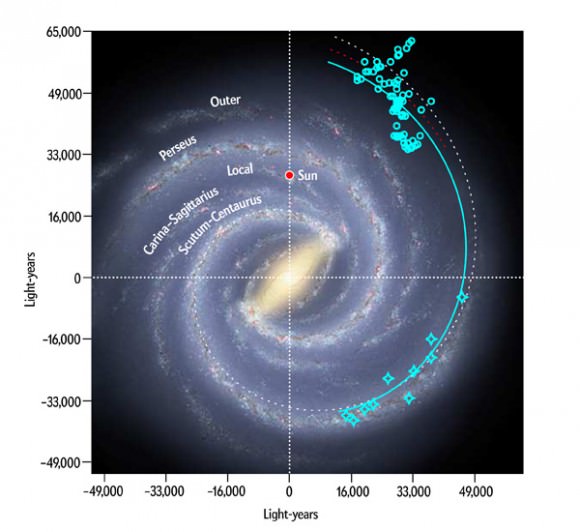

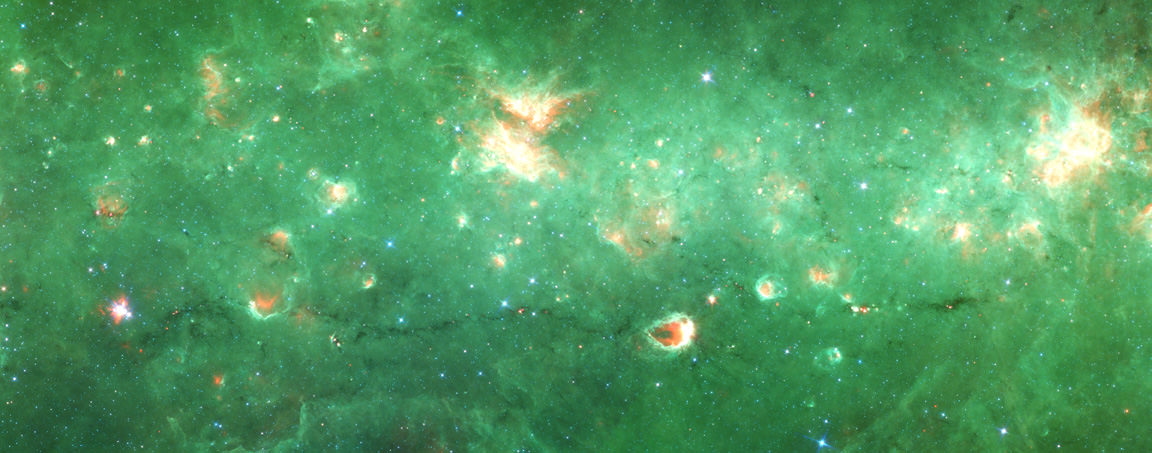

It’s right over there, in the direction of the Sagittarius constellation. Located just 26,000 light-years away. And as we speak, it’s in the process of tearing apart entire stars and star systems, occasionally consuming them, adding to its mass like a voracious shark.

Wait, that doesn’t sound cool, that sort of sounds a little scary. Right?

Don’t worry, you have absolutely nothing to worry about, unless you plan to live for quadrillions of years, which I do, thanks to my future robot body. I’m ready for my singularity, Dr. Kurzweil.

Is the supermassive black hole going to consume the Milky Way? If not, why not? If so, why so?

The discovery of a supermassive black hole at the heart of the Milky Way, and really almost all galaxies, is one of my favorite discoveries in the field of astronomy. It’s one of those insights that simultaneously answered some questions, and opened up even more.

Back in the 1970s, the astronomers Bruce Balick and Robert Brown realized that there was an intense source of radio emissions coming from the very center of the Milky Way, in the constellation Sagittarius.

They designated it Sgr A*. The asterisk stands for exciting. You think I’m joking, but I’m not. For once, I’m not joking.

In 2002, astronomers observed that there were stars zipping past this object, like comets on elliptical paths going around the Sun. Imagine the mass of our Sun, and the tremendous power it would take to wrench a star like that around.

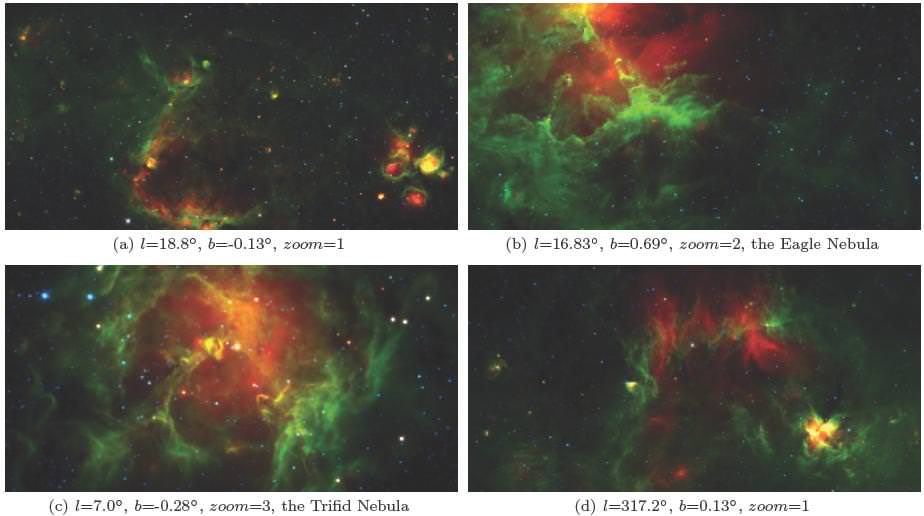

The only objects with that much density and gravity are black holes, but in this case, a black hole with millions of times the mass of our own Sun: a supermassive black hole.

With the discovery of the Milky Way’s supermassive black hole, astronomers found evidence that there are black holes at the heart of every galaxy.

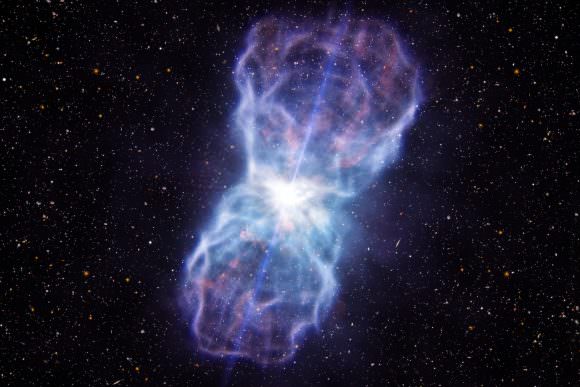

At the same time, the discovery of supermassive black holes helped answer one of the big questions in astronomy: what are quasars? We did a whole article on them, but they’re intensely bright objects, generating enough light they can be seen billions of light-years away. Giving off more energy than the rest of their own galaxy combined.

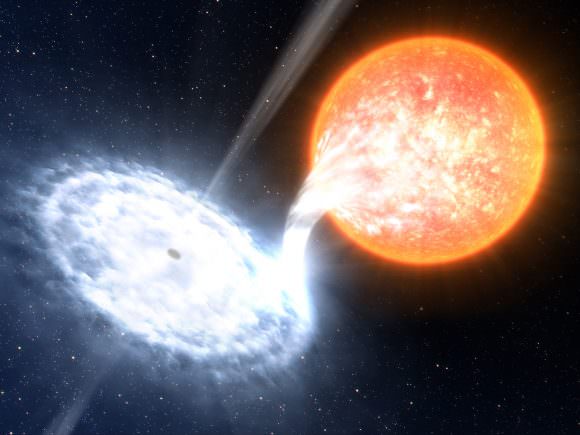

It turns out that quasars and supermassive black holes are the same thing. Quasars are just black holes in the process of actively feeding; gobbling up so much material it piles up in an accretion disk around it. Once again, these do sound terrifying. But are we in any danger?

In the short term, no. The black hole at the center of the Milky Way is 26,000 light-years away. Even if it turned into a quasar and started eating stars, you wouldn’t even be able to notice it from this distance.

A black hole is just a concentration of mass in a very small region, which things orbit around. To give you an example, you could replace the Sun with a black hole with the exact same mass, and nothing would change. I mean, we’d all freeze because there wasn’t a Sun in the sky anymore, but the Earth would continue to orbit this black hole in exactly the same orbit, for billions of years.

Same goes with the black hole at the center of the Milky Way. It’s not pulling material in like a vacuum cleaner, it serves as a gravitational anchor for a group of stars to orbit around, for billions of years.

In order for a black hole to actually consume a star, it needs to make a direct hit. To get within the event horizon, which is only about 17 times bigger than the Sun. If a star gets close, without hitting, it’ll get torn apart, but still, it doesn’t happen very often.

The problem happens when these stars interact with one another through their own gravity, and mess with each other’s orbits. A star that would have been orbiting happily for billions of years might get deflected into a collision course with the black hole. But this happens very rarely.

Over the short term, that supermassive black hole is totally harmless. Especially from out here in the galactic suburbs.

But there are a few situations that might cause some problems over vast periods of time.

The first panic will happen when the Milky Way collides with Andromeda in about 4 billion years – let’s call this mess Milkdromeda. Suddenly, you’ll have two whole clouds of stars interacting in all kinds of ways, like an unstable blended family. Stars that would have been safe will careen past other stars and be deflected down into the maw of either of the two supermassive black holes on hand. Andromeda’s black hole could be 100 million times the mass of the Sun, so it’s a bigger target for stars with a death wish.

Over the coming billions, trillions and quadrillions of years, more and more galaxies will collide with Milkdromeda, bringing new supermassive black holes and more stars to the chaos.

So many opportunities for mayhem.

Of course, the Sun will die in about 5 billion years, so this future won’t be our problem. Well, fine, with my eternal robot body, it might still be my problem.

After our neighborhood is completely out of galaxies to consume, then there will just be countless eons of time for stars to interact for orbit after orbit. Some will get flung out of Milkdromeda, some will be hurled down into the black hole.

And others will be safe, assuming they can avoid this fate over the Googol years it’ll take for the supermassive black hole to finally evaporate. That’s a 1 followed by 100 zeroes years. That’s a really really long time, so now I don’t like those odds.

For our purposes, the black hole at the heart of the Milky Way is completely and totally safe. In the lifetime of the Sun, it won’t interact with us in any way, or consume more than a handful of stars.

But over the vast eons, it could be a different story. I hope we can be around to find out the answer.