Welcome to the 583rd Carnival of Space! The Carnival is a community of space science and astronomy writers and bloggers, who submit their best work each week for your benefit. We have a fantastic roundup today so now, on to this week’s worth of stories!

Continue reading “Carnival of Space #583”

The Milky Way is Still Rippling from a Galactic Collision Millions of Years Ago

Between 300 million and 900 million years ago, our Milky Way galaxy nearly collided with the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy. Data from the ESA’s Gaia mission shows the ongoing effect of this event, with stars moving like ripples on the surface of a pond. The galactic collision is part of an ongoing cannibalization of the dwarf galaxy by the much-larger Milky Way.

Continue reading “The Milky Way is Still Rippling from a Galactic Collision Millions of Years Ago”

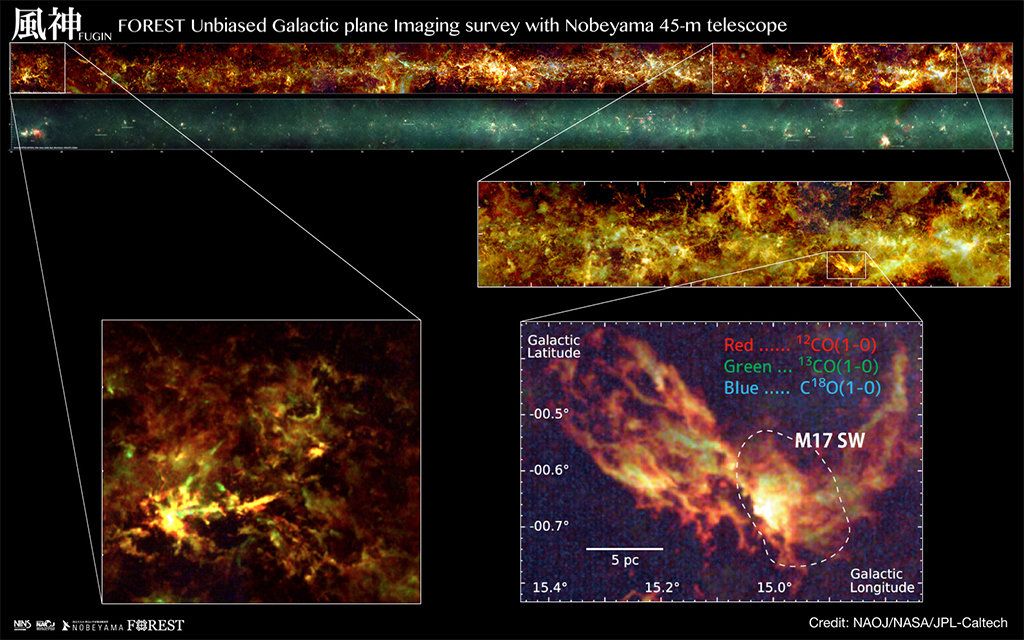

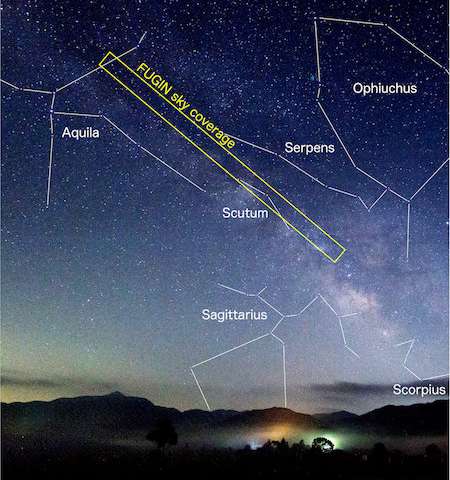

The Most Detailed Map Ever Made of the Milky Way in Radio Waves

A Japanese telescope has produced our most detailed radio wave image yet of the Milky Way galaxy. Over a 3-year time period, the Nobeyama 45 meter telescope observed the Milky Way for 1100 hours to produce the map. The image is part of a project called FUGIN (FOREST Unbiased Galactic plane Imaging survey with the Nobeyama 45-m telescope.) The multi-institutional research group behind FUGIN explained the project in the Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan and at arXiv.

The Nobeyama 45 meter telescope is located at the Nobeyama Radio Observatory, near Minamimaki, Japan. The telescope has been in operation there since 1982, and has made many contributions to millimeter-wave radio astronomy in its life. This map was made using the new FOREST receiver installed on the telescope.

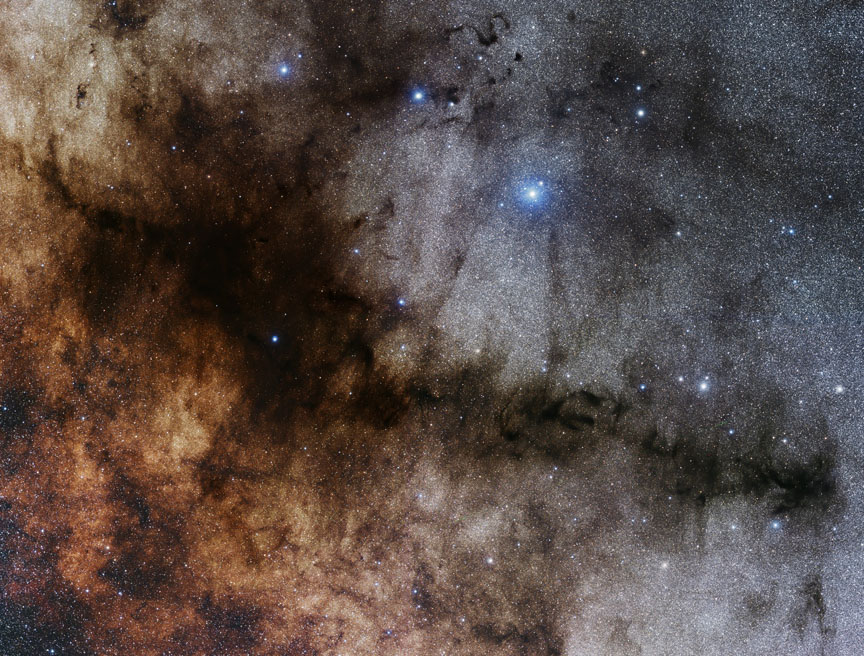

When we look up at the Milky Way, an abundance of stars and gas and dust is visible. But there are also dark spots, which look like voids. But they’re not voids; they’re cold clouds of molecular gas that don’t emit visible light. To see what’s happening in these dark clouds requires radio telescopes like the Nobeyama.

The Nobeyama was the largest millimeter-wave radio telescope in the world when it began operation, and it has always had great resolution. But the new FOREST receiver has improved the telescope’s spatial resolution ten-fold. The increased power of the new receiver allowed astronomers to create this new map.

The new map covers an area of the night sky as wide as 520 full Moons. The detail of this new map will allow astronomers to study both large-scale and small-scale structures in new detail. FUGIN will provide new data on large structures like the spiral arms—and even the entire Milky Way itself—down to smaller structures like individual molecular cloud cores.

FUGIN is one of the legacy projects for the Nobeyama. These projects are designed to collect fundamental data for next-generation studies. To collect this data, FUGIN observed an area covering 130 square degrees, which is over 80% of the area between galactic latitudes -1 and +1 degrees and galactic longitudes from 10 to 50 degrees and from 198 to 236 degrees. Basically, the map tried to cover the 1st and 3rd quadrants of the galaxy, to capture the spiral arms, bar structure, and the molecular gas ring.

The aim of FUGIN is to investigate physical properties of diffuse and dense molecular gas in the galaxy. It does this by simultaneously gathering data on three carbon dioxide isotopes: 2CO, 13CO, and 18CO. Researchers were able to study the distribution and the motion of the gas, and also the physical characteristics like temperature and density. And the studying has already paid off.

FUGIN has already revealed things previously hidden. They include entangled filaments that weren’t obvious in previous surveys, as well as both wide-field and detailed structures of molecular clouds. Large scale kinematics of molecular gas such as spiral arms were also observed.

But the main purpose is to provide a rich data-set for future work by other telescopes. These include other radio telescopes like ALMA, but also telescopes operating in the infrared and other wavelengths. This will begin once the FUGIN data is released in June, 2018.

Millimeter wave radio astronomy is powerful because it can “see” things in space that other telescopes can’t. It’s especially useful for studying the large, cold gas clouds where stars form. These clouds are as cold as -262C (-440F.) At temperatures that low, optical scopes can’t see them, unless a bright star is shining behind them.

Even at these extremely low temperatures, there are chemical reactions occurring. This produces molecules like carbon monoxide, which was a focus of the FUGIN project, but also others like formaldehyde, ethyl alcohol, and methyl alcohol. These molecules emit radio waves in the millimeter range, which radio telescopes like the Nobeyama can detect.

The top-level purpose of the FUGIN project, according to the team behind the project, is to “provide crucial information about the transition from atomic gas to molecular gas, formation of molecular clouds and dense gas, interaction between star-forming regions and interstellar gas, and so on. We will also investigate the variation of physical properties and internal structures of molecular clouds in various environments, such as arm/interarm and bar, and evolutionary stage, for example, measured by star-forming activity.”

This new map from the Nobeyama holds a lot of promise. A rich data-set like this will be an important piece of the galactic puzzle for years to come. The details revealed in the map will help astronomers tease out more detail on the structures of gas clouds, how they interact with other structures, and how stars form from these clouds.

The Night Sky Magic of the Atacama

There’s nothing an astronomer – whether professional or amateur – loves more than a clear dark night sky away from the city lights. Outside the glare and glow and cloud cover that most of us experience every day, the night sky comes alive with a life of its own.

Thousands upon countless thousands of glittering jewels – each individual star a pinprick of light set against the velvet-smooth blackness of the deeper void. The arching band of the Milky Way, itself host to billions more stars so far away that we can only see their combined light from our vantage point. The familiar constellations, proudly showing their true character, drawing the eye and the mind to the ancient tales spun about them.

There are few places left in the world to see the sky as our ancestors did; to gaze in wonder at the celestial dome and feel the weight of billions of years of cosmic history hanging above us. Thankfully the International Dark Sky Association is working to preserve what’s left of the true night sky, and they’ve rightfully marked northern Chile to preserve for posterity.

Astronomy Cast Ep. 455: Your Practical Guide to Colonizing the Milky Way!

This episode was recorded live in St. Louis, MO at the Astronomy Cast Solar Eclipse Escape 2017, so there’s only audio, no video. Listen here at Astronomy Cast as we discuss how humans might be able to colonize the Milky Way!

We usually record Astronomy Cast every Friday at 1:30 pm PDT / 4:30 pm EDT/ 20:30 PM UTC (8:30 GMT). You can watch us live on AstronomyCast.com, or the AstronomyCast YouTube page.

Visit the Astronomy Cast Page to subscribe to the audio podcast!

If you would like to support Astronomy Cast, please visit our page at Patreon here – https://www.patreon.com/astronomycast. We greatly appreciate your support!

If you would like to join the Weekly Space Hangout Crew, visit their site here and sign up. They’re a great team who can help you join our online discussions!

Can Astronauts See Stars From the Space Station?

I’ve often been asked the question, “Can the astronauts on the Space Station see the stars?” Astronaut Jack Fischer provides an unequivocal answer of “yes!” with a recent post on Twitter of a timelapse he took from the ISS. Fischer captured the arc of the Milky Way in all its glory, saying it “paints the heavens in a thick coat of awesome-sauce!”

Can you see stars from up here? Oh yeah baby! Check out the Milky Way as it spins & paints the heavens in a thick coat of awesome-sauce! pic.twitter.com/MsXeNHPxLF

— Jack Fischer (@Astro2fish) August 16, 2017

But, you might be saying, “how can this be? I thought the astronauts on the Moon couldn’t see any stars, so how can anyone see stars in space?”

It is a common misconception that the Apollo astronauts didn’t see any stars. While stars don’t show up in the pictures from the Apollo missions, that’s because the camera exposures were set to allow for good images of the bright sunlit lunar surface, which included astronauts in bright white space suits and shiny spacecraft. Apollo astronauts reported they could see the brighter stars if they stood in the shadow of the Lunar Module, and also they saw stars while orbiting the far side of the Moon. Al Worden from Apollo 15 has said the sky was “awash with stars” in the view from the far side of the Moon that was not in daylight.

Just like stargazers on Earth need dark skies to see stars, so too when you’re in space.

The cool thing about being in the ISS is that astronauts experience nighttime 16 times a day (in 45 minute intervals) as they orbit the Earth every 90 minutes, and can have extremely dark skies when they are on the “dark” side of Earth. Here’s another recent picture from Fischer where stars can be seen:

Twinkle, twinkle, little star…

Up above the world so high

Like a diamond in the sky… pic.twitter.com/8H7CshyP0p— Jack Fischer (@Astro2fish) August 13, 2017

For stars to show up in any image, its all about the exposure settings. For example, if you are outside (on Earth) on a dark night and can see thousands of stars, if you just take your camera or phone camera and snap a quick picture, you’ll just get a darkness. Earth-bound astrophotographers need long-exposure shots to capture the Milky Way. Same is true with ISS astronauts: if they take long-exposure shots, they can get stunning images like this one:

This image, set to capture the bright solar arrays and the rather bright Earth (even though its in twilight) reveals no stars:

Sometimes you look out the window and it just takes your breath away from how beautiful Earth is. Today is one of those times… #EarthShapes pic.twitter.com/53UqL9BFH1

— Jack Fischer (@Astro2fish) August 2, 2017

In this timelapse of Earth at night, a few stars show up, but again, the main goal here was to have the camera capture the Earth:

Universe Today’s Bob King has a good, detailed explanation of how astronauts on the ISS can see stars on his Astro Bob blog Astrophysicist . Brian Koberlein explains it on his blog, here.

You can check out all the images that NASA astronauts take from the ISS on the “Astronaut Photography of Earth” site, and almost all the ISS astronauts and cosmonauts have social media accounts where they post pictures. Jack Fischer, currently on board, tweets great images and videos frequently here.

What Is the Name Of Our Galaxy?

Since prehistoric times, human beings have looked up at at the night sky and pondered the mystery of the band of light that stretches across the heavens. And while theories have been advanced since the days of Ancient Greece as to what it could be, it was only with the birth of modern astronomy that scholars have come come to know precisely what it is – i.e. countless stars at considerable distances from Earth.

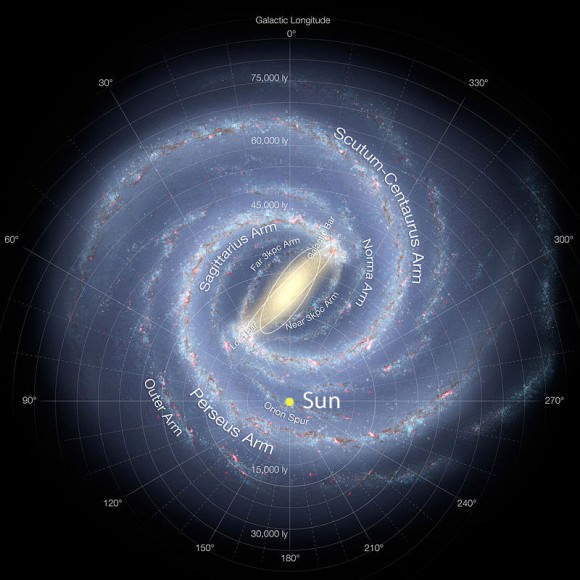

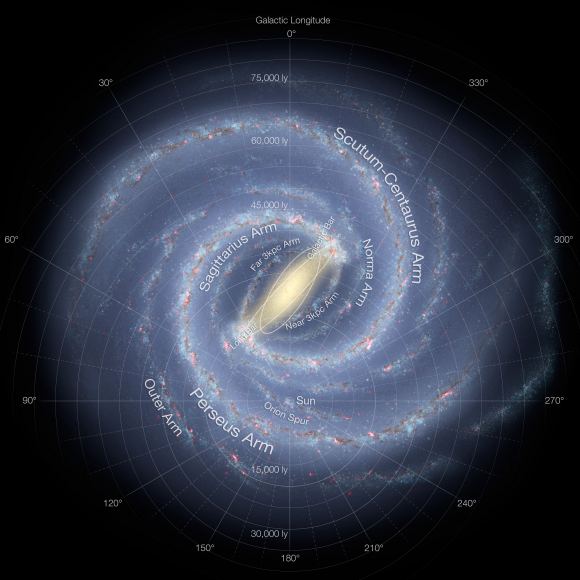

The term “Milky Way”, a term which emerged in Classical Antiquity to describe the band of light in the night sky, has since gone on to become the name for our galaxy. Like many others in the known Universe, the Milky Way is a barred, spiral galaxy that is part of the Local Group – a collection of 54 galaxies. Measuring 100,000 – 180,000 light-years in diameter, the Milky Way consists of between 100 and 400 billion stars.

Structure:

The Milky Way consists of a Galactic Center that is shaped like a bar and a Galactic Disk made up of spiral arms, all of which is surrounded by the Halo – which is made up of old stars and globular clusters. The Center, also known as “the bulge”, is a dense concentration of mostly old stars that measures about 10,000 light years in radius. This region is also the rotational center of the Milky Way.

The Galactic Center is also home to an intense radio source named Sagittarius A*, which is believed to have a supermassive black hole (SMBH) at its center. The presence of this black hole has been discerned due to the apparent gravitational influence it has on surrounding stars. Astronomers estimate that it has a mass of between 4.1. and 4.5 million Solar masses.

Outside the barred bulge at the Galactic Center is the Galactic Disk of the Milky Way. This consists of stars, gas and dust which is organized into four spiral arms. These arms typically contain a higher density of interstellar gas and dust than the Galactic average, as well as a greater concentration of star formation. While there is no consensus on the exact structure or extent of these spiral arms, they are commonly grouped into two or four different arms.

In the case of four arms, this is based on the traced paths of gas and younger stars in our galaxy, which corresponds to the Perseus Arm, the Norma and Outer Arm, the Scutum-Centaurum Arm, and the Carina-Sagittarius Arm. There are also at least two smaller arms, which include the Cygnus Arm and the Orion Arm. Meanwhile, surveys based on the presence of older stars show only two major spirals arms – the Perseus arm and the Scutum–Centaurus arm.

Beyond the Galactic Disk is the Halo, which is made up of old stars and globular clusters – 90% of which lie within 100,000 light-years (30,000 parsecs) from the Galactic Center. Recent evidence provided by X-ray observatories indicates that in addition to this stellar halo, the Milky way also has a halo of hot gas that extends for hundreds of thousands of light years.

Size and Mass:

The Galactic Disk of the Milky Way Galaxy is approximately 100,000 light years in diameter and about 1,000 light years thick. It is estimated to contain between 100 and 400 billion stars, though the exact figure depends on the number of very low-mass M-type (aka. red dwarf) stars. This is difficult to determine because these stars also have low-luminosity compared to other class.

The distance from the Sun to the Galactic Center is estimated to be between 25,000 to 28,000 light years (7,600 to 8,700 parsecs). The Galactic Center’s bar (aka. its “bulge”) is thought to be about 27,000 light-years in length and is composed primarily of red stars, all of which are thought to be ancient. The bar is surrounded by the ‘5-kpc ring’, a region that contains much of the galaxy’s molecular hydrogen and where star-formation is most intense.

The Galactic Disk has a diameter of between 70,000 and 100,000 light-years. It does not have a sharp edge, a radius beyond which there are no stars. However, the number of stars drops slowly with distance from the center. Beyond a radius of roughly 40,000 light years, the number of stars drops much faster the farther you get from the center.

Location of the Solar System:

The Solar System is located near the inner rim of the Orion Arm, a minor spiral arm located between the Carina–Sagittarius Arm and the Perseus Arm. This arm measures some 3,500 light-years (1,100 parsecs) across, approximately 10,000 light-years (3,100 parsecs) in length, and is at a distance of about 25,400 to 27,400 light years (7.78 to 8.4 thousand parsecs) from the Galactic Center.

History of Observation:

Our galaxy was named because of the way the haze it casts in the night sky resembled spilled milk. This name is also quite ancient. It is translation from the Latin “Via Lactea“, which in turn was translated from the Greek for Galaxias, referring to the pale band of light formed by stars in the galactic plane as seen from Earth.

Persian astronomer Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1201–1274) even spelled it out in his book Tadhkira: “The Milky Way, i.e. the Galaxy, is made up of a very large number of small, tightly clustered stars, which, on account of their concentration and smallness, seem to be cloudy patches. Because of this, it was likened to milk in color.”

Astronomers had long suspected the Milky Way was made up of stars, but it wasn’t proven until 1610, when Galileo Galilei turned his rudimentary telescope towards the heavens and resolved individual stars in the band across the sky. With the help of telescopes, astronomers realized that there were many, many more stars in the sky, and that all of the ones that we can see are a part of the Milky Way.

In 1755, Immanuel Kant proposed that the Milky Way was a large collection of stars held together by mutual gravity. Just like the Solar System, this collection would be rotating and flattened out as a disk, with the Solar System embedded within it. Astronomer William Herschel (discoverer of Uranus) tried to map its shape in 1785, but he didn’t realize that large portions of the galaxy are obscured by gas and dust, which hide its true shape.

It wasn’t until the 1920s, when Edwin Hubble provided conclusive evidence that the spiral nebulae in the sky were actually whole other galaxies, that the true shape of our galaxy was known. Thenceforth, astronomers came to understand that the Milky Way is a barred, spiral galaxy, and also came to appreciate how big the Universe truly is.

The Milky Way is appropriately named, being the vast and cloudy mass of stars, dust and gas it is. Like all galaxies, ours is believed to have formed from many smaller galaxies colliding and combining in the past. And in 3 to 4 billion years, it will collide with the Andromeda Galaxy to form an even larger mass of stars, gas and dust. Assuming humanity still exists by then (and survives the process) it should make for some interesting viewing!

We have written many interesting articles about the Milky Way here at Universe Today. Here’s 10 Interesting Facts About the Milky Way, How Big is the Milky Way?, Why is our Galaxy Called the Milky Way?, What is the Closest Galaxy to the Milky Way?, Where is the Earth in the Milky Way?, The Milky Way has Only Two Spiral Arms, and It’s Inevitable: Milky Way, Andromeda Galaxy Heading for Collision.

If you’d like more info on galaxies, check out Hubblesite’s News Releases on Galaxies, and here’s NASA’s Science Page on Galaxies.

We’ve also recorded an episode of Astronomy Cast about the Milky Way. Listen here, Episode 99: The Milky Way.

Sources:

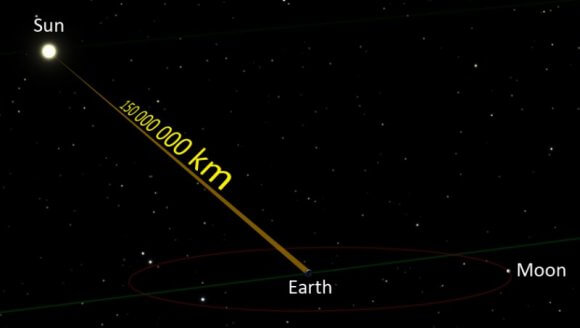

How Much Stuff is in a Light Year?

The Milky Way is an extremely big place. Measured from end to end, our galaxy in an estimated 100,000 to 180,000 light years (31,000 – 55,000 parsecs) in diameter. And it is extremely well-populated, with an estimated 100 to 400 million stars contained within. And according to recent estimates, it is believed that there are as many as 100 billion planets in the Milky Way. And our galaxy is merely one of trillions within the Universe.

So if we were to break it down, just how much matter would we find out there? Estimating how much there is overall would involve some serious math and incredible figures. But what about a single light year? As the most commonly-used unit for measuring the distances between stars and galaxies, determining how much stuff can be found within a single light year (on average) is a good way to get an idea of how stuff is out there.

Light Year:

Even though the name is a little confusing, you probably already know that a light year is the distance that light travels in the space of a year. Given that the speed of light has been measured to 299,792, 458 m/s (1080 million km/h; 671 million mph), the distance light travels in a single year is quite immense. All told, a single light year works out to 9,460,730,472,580.8 kilometers (5,878,625,373,183.6 mi).

So to determine how much stuff is in a light year, we need to take that distance and turn it into a cube, with each side measuring one light year in length. Imagine that giant volume of space (a little challenging for some of us to get our heads around) and imagine just how much “stuff” would be in there. And not just “stuff”, in the sense of dust, gas, stars or planets, either. How much nothing is in there, as in, the empty vacuum of space?

There is an answer, but it all depends on where you put your giant cube. Measure it at the core of the galaxy, and there are stars buzzing around all over the place. Perhaps in the heart of a globular cluster? In a star forming nebula? Or maybe out in the suburbs of the Milky Way? There’s also great voids that exist between galaxies, where there’s almost nothing.

Density of the Milky Way:

There’s no getting around the math in this one. First, let’s figure out an average density for the Milky Way and then go from there. Its about 100,000 to 180,000 light-years across and 1000 light-years thick. According to my buddy and famed astronomer Phil Plait (of Bad Astronomy), the total volume of the Milky Way is about 8 trillion cubic light-years.

And the total mass of the Milky Way is 6 x 1042 kilograms (that’s 6,000 trillion trillion trillion metric tons or 6,610 trillion trillion trillion US tons). Divide those together and you get 8 x 1029 kilograms (800 trillion trillion metric tons or 881.85 trillion trillion US tons) per light year. That’s an 8 followed by 29 zeros. This sounds like a lot, but its actually the equivalent of 0.4 Solar Masses – 40% of the mass of our Sun.

In other words, on average, across the Milky Way, there’s about 40% the mass of the Sun in every cubic light year. But in an average cubic meter, there’s only about 950 attograms, which is almost one femtogram (a quadrillionth of a gram of matter), which is pretty close to nothing. Compare this to air, which has more than a kilogram of mass per cubic meter.

To be fair, in the densest regions of the Milky Way – like inside globular clusters – you can get densities of stars with 100, or even 1000 times greater than our region of the galaxy. Stars can get as close together as the radius of the Solar System. But out in the vast interstellar gulfs between stars, the density drops significantly. There are only a few hundred individual atoms per cubic meter in interstellar space.

And in the intergalactic voids; the gulfs between galaxies, there are just a handful of atoms per meter. Like it or not, much of the Universe is pretty close to being empty space, with just trace amounts of dust or gas particles to be found between all the stars, galaxies, clusters and super clusters.

So how much stuff is there in a light year? It all depends on where you look, but if you spread all the matter around by shaking the Universe up like a snow globe, the answer is very close to nothing.

We have written many interesting articles about the Milky Way Galaxy here at Universe Today. Here’s 10 Interesting Facts About the Milky Way, How Big is the Milky Way?, How Many Stars are There in the Milky Way?, Where is the Earth Located in the Milky Way?, How Far is a Light Year?, and How Far Does Light Travel in a Year?

For more information, check out How many teaspoons are there in a cubic light year? at HowStuffWorks

Astronomy Cast also has a good episode on the subject. Here’s Episode 99: The Milky Way

Sources:

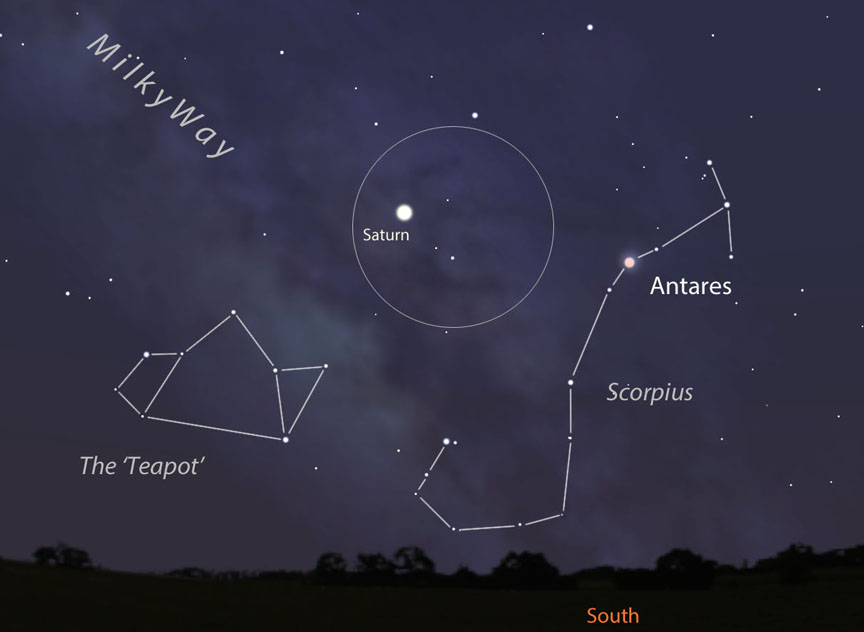

Saturn Rides Bareback On The Galactic Dark Horse

I didn’t notice it with the naked eye, but as soon as the time exposure ended and I looked at the camera’s back display, there it was — Saturn riding barebacked on the Galactic Dark Horse! The horse, more of a prancing pony, is a collection of dark nebulae in the southern sky beautifully placed for viewing on late June evenings. The Dark Horse is part of the Great Rift, a dark gap that splits the band of the Milky Way in half, starting at the Northern Cross and extending all the way down to the “Teapot” of Sagittarius in the south.

While appearing to be little more than empty, starless space, in reality the Rift consists of enormous clouds of cosmic dust and gas in the plane of the galaxy called dark nebulae that blot out the light of more distant stars. If you could suck it all up with a monster vacuum cleaner and expose the billions of stars otherwise hidden, the Milky Way would cast obvious shadows — even suburban skywatchers would routinely see it.

Tiny dust particles spewed by older, evolved stars and exploding supernovas have been settling in the plane of the galaxy since its birth 13.2 billion years ago. While the dust is sparse, it adds up over the light years to form a thick, dark band silhouetted against the more distant stars. Gravity has been at work on the dust since the earliest days, compressing the denser clumps into new stars and star clusters. But much raw material remains. Within the curdles of dark nebulae, astronomers use dust-penetrating infrared and radio telescopes to watch new stars in the process of incubation.

There are more obvious parts of the Rift to the naked eye but few conjure up as striking an image as the Dark Horse, located about one outstretched fist to the left of the Scorpius’ brightest star, Antares. Saturn sits astride the horse’s back or eastern side. While it’s fun to see the horse as a single figure, astronomers catalog the various body parts as individual dark nebulae with separate numbers and even names. The largest part of the horse, the hind leg, is nicknamed the Pipe Nebula and lies 600-700 light years away. The Pipe is further subdivided into B59, B72, B77 and B78, from a survey of dark nebulae by early 20th century American astronomer E.E. Barnard.

While the dark horse shows up well in time-exposure photos, you’ll need dark, rural skies to view it with the naked eye. It’s only a couple fists high for those of us living in the northern U.S. and southern Canada, but considerably higher up from the southern states and points south. The figure is large but faint, about 10° long by 7° wide, and stands due south and highest in the sky around 12:30 a.m. in late June. Allow your eyes time to fully dark adapt beforehand. Try for the dark rump and hind leg first then work from there to fill in the rest of the horse.

Once I knew what to look for, I could fleetingly see the entire horse with its various protrusions as a subtle darkness against the brighter Milky Way. Averted vision, the technique of playing your eye around the subject rather than staring directly at it, helped make it happen. Wide-field binoculars will show it easily and in greater detail against a fabulously rich star field.

The best time to horse around under the Milky Way happens from now till the end of the month, when the bright Moon sends the critter into hiding.

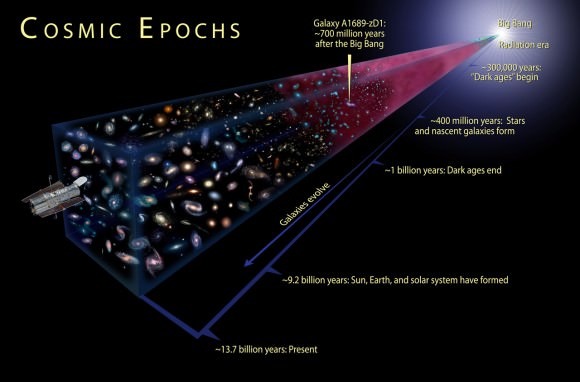

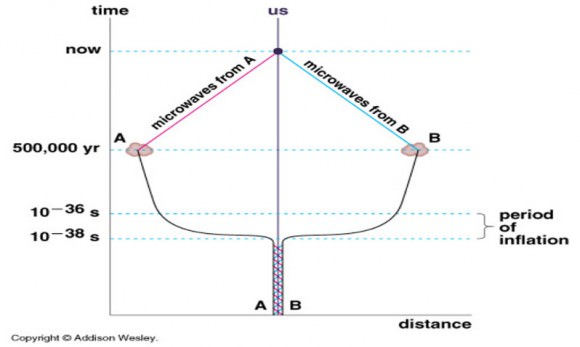

What Was Cosmic Inflation? The Quest to Understand the Earliest Universe

The Big Bang. The discovery that the Universe has been expanding for billions of years is one of the biggest revelations in the history of science. In a single moment, the entire Universe popped into existence, and has been expanding ever since.

We know this because of multiple lines of evidence: the cosmic microwave background radiation, the ratio of elements in the Universe, etc. But the most compelling one is just the simple fact that everything is expanding away from everything else. Which means, that if you run the clock backwards, the Universe was once an extremely hot dense region

Let’s go backwards in time, billions of years. The closer you get to the Big Bang, the closer everything was, and the hotter it was. When you reach about 380,000 years after the Big Bang, the entire Universe was so hot that all matter was ionized, with atomic nuclei and electrons buzzing around each other.

Keep going backwards, and the entire Universe was the temperature and density of a star, which fused together the primordial helium and other elements that we see to this day.

Continue to the beginning of time, and there was a point where everything was so hot that atoms themselves couldn’t hold together, breaking into their constituent protons and neutrons. Further back still and even atoms break apart into quarks. And before that, it’s just a big question mark. An infinitely dense Universe cosmologists called the singularity.

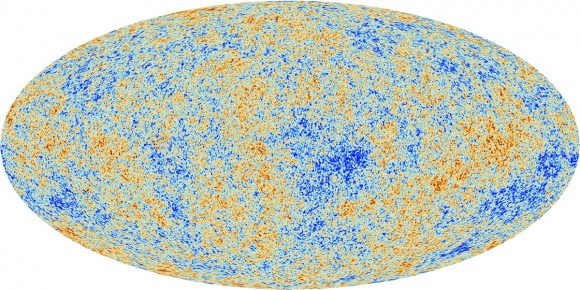

When you look out into the Universe in all directions, you see the cosmic microwave background radiation. That’s that point when the Universe cooled down so that light could travel freely through space.

And the temperature of this radiation is almost exactly the same in all directions that you look. There are tiny tiny variations, detectable only by the most sensitive instruments.

When two things are the same temperature, like a spoon in your coffee, it means that those two things have had an opportunity to interact. The coffee transferred heat to the spoon, and now their temperatures have equalized.

When we see this in opposite sides of the Universe, that means that at some point, in the ancient past, those two regions were touching. That spot where the light left 13.8 billion years ago on your left, was once directly touching that spot on your right that also emitted its light 13.8 billion years ago.

This is a great theory, but there’s a problem: The Universe never had time for those opposite regions to touch. For the Universe to have the uniform temperature we see today, it would have needed to spend enough time mixing together. But it didn’t have enough time, in fact, the Universe didn’t have any time to exchange temperature.

Imagine you dipped that spoon into the coffee and then pulled it out moments later before the heat could transfer, and yet the coffee and spoon are exactly the same temperature. What’s going on?

To address this problem, the cosmologist Alan Guth proposed the idea of cosmic inflation in 1980. That moments after the Big Bang, the entire Universe expanded dramatically.

And by “moments”, I mean that the inflationary period started when the Universe was only 10^-36 seconds old, and ended when the Universe was 10^-32 seconds old.

And by “expanded dramatically”, I mean that it got 10^26 times larger. That’s a 1 followed by 26 zeroes.

Before inflation, the observable Universe was smaller than an atom. After inflation, it was about 0.88 millimeters. Today, those regions have been stretched 93 billion light-years apart.

This concept of inflation was further developed by cosmologists Andrei Linde, Paul Steinhardt, Andy Albrecht and others.

Inflation resolved some of the shortcomings of the Big Bang Theory.

The first is known as the flatness problem. The most sensitive satellites we have today measure the Universe as flat. Not like a piece-of-paper-flat, but flat in the sense that parallel lines will remain parallel forever as they travel through the Universe. Under the original Big Bang cosmology, you would expect the curvature of the Universe to grow with time.

The second is the horizon problem. And this is the problem I mentioned above, that two regions of the Universe shouldn’t have been able to see each other and interact long enough to be the same temperature.

The third is the monopole problem. According to the original Big Bang theory, there should be a vast number of heavy, stable “monopoles”, or a magnetic particle with only a single pole. Inflation diluted the number of monopoles in the Universe so don’t detect them today.

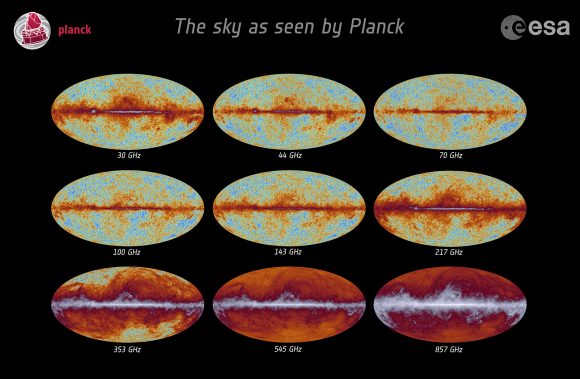

Although the cosmic microwave background radiation appears mostly even across the sky, there could still be evidence of that inflationary period baked into it.

In order to do this, astronomers have been focusing on searching for primordial gravitational waves. These are different from the gravitational waves generated through the collision of massive objects. Primordial gravitational waves are the echoes from that inflationary period which should be theoretically detectable through the polarization, or orientation, of light in the cosmic microwave background radiation.

A collaboration of scientists used an instrument known as the Background Imaging of Cosmic Extragalactic Polarization (or BICEP2) to search for this polarization, and in 2014, they announced that maybe, just maybe, they had detected it, proving the theory of cosmic inflation was correct.

Unfortunately, another team working with the space-based Planck telescope posted evidence that the fluctuations they saw could be fully explained by intervening dust in the Milky Way.

The problem is that BICEP2 and Planck are designed to search for different frequencies. In order to really get to the bottom of this question, more searches need to be done, scanning a series of overlapping frequencies. And that’s in the works now.

BICEP2 and Planck and the newly developed South Pole Telescope as well as some observatories in Chile are all scanning the skies at different frequencies at the same time. Distortion from various types of foreground objects, like dust or radiation should be brighter or dimmer in the different frequencies, while the light from the cosmic microwave background radiation should remain constant throughout.

There are more telescopes, searching more wavelengths of light, searching more of the sky. We could know the answer to this question with more certainty shortly.

One of the most interesting implications of cosmic inflation, if proven, is that our Universe is actually just one in a vast multiverse. While the Universe was undergoing that dramatic expansion, it could have created bubbles of spacetime that spawned other universes, with different laws of physics.

In fact, the father of inflation, Alan Guth, said, “It’s hard to build models of inflation that don’t lead to a multiverse.”

And so, if inflation does eventually get confirmed, then we’ll have a whole multiverse to search for in the cosmic microwave background radiation.

The Big Bang was one of the greatest theories in the history of science. Although it did have a few problems, cosmic inflation was developed to address them. Although there have been a few false starts, astronomers are now performing a sensitive enough search that they might find evidence of this amazing inflationary period. And then it’ll be Nobel Prizes all around.