There are times when I really wish astronomers could take their advanced modern knowledge of the cosmos and then go back and rewrite all the terminology so that they make more sense. For example, dark matter and dark energy seem like they’re linked, and maybe they are, but really, they’re just mysteries.

Is dark matter actually matter, or just a different way that gravity works over long distances? Is dark energy really energy, or is it part of the expansion of space itself. Black holes are neither black, nor holes, but that doesn’t stop people from imagining them as dark tunnels to another Universe. Or the Big Bang, which makes you think of an explosion.

Another category that could really use a re-organizing is the term nova, and all the related objects that share that term: nova, supernova, hypernova, meganova, ultranova. Okay, I made those last couple up.

I guess if you go back to the basics, a nova is a star that momentarily brightens up. And a supernova is a star that momentarily brightens up… to death. But the underlying scenario is totally different.

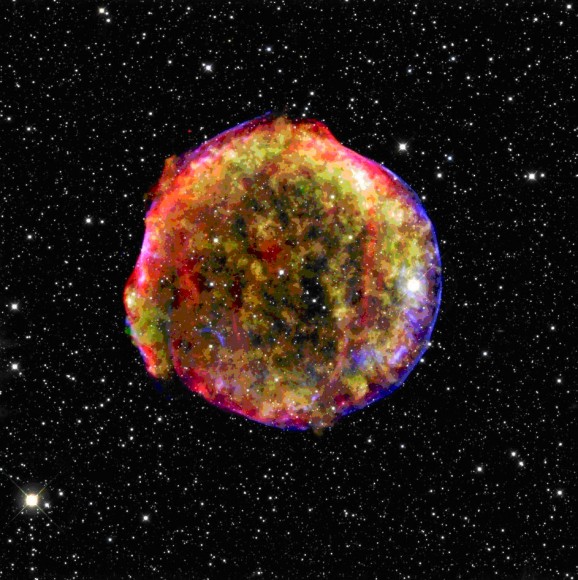

As we’ve mentioned in many articles already, a supernova commonly occurs when a massive star runs out of fuel in its core, implodes, and then detonates with an enormous explosion. There’s another kind of supernova, but we’ll get to that later.

A plain old regular nova, on the other hand, happens when a white dwarf – the dead remnant of a Sun-like star – absorbs a little too much material from a binary companion. This borrowed hydrogen undergoes fusion, which causes it to brighten up significantly, pumping up to 100,000 times more energy off into space.

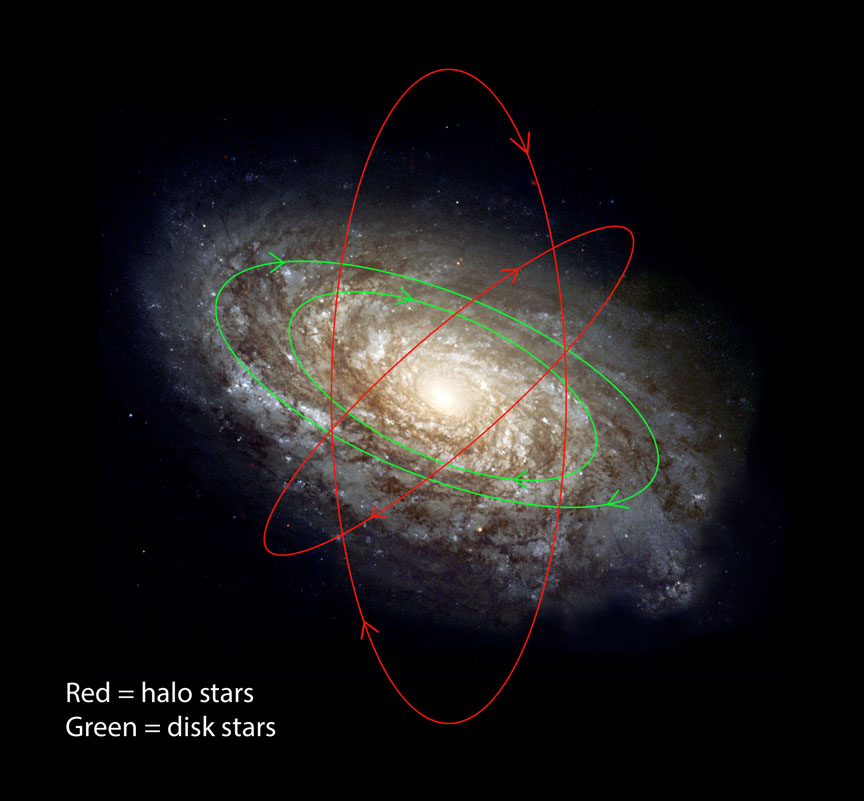

Imagine a situation where you’ve got two main sequence stars like our Sun orbiting one another in a tight binary system. Over the course of billions of years, one of the stars runs out of fuel in its core, expands as a red giant, and then contracts back down into a white dwarf. It’s dead.

Some time later, the second star dies, and it expands as a red giant. So now you’ve got a red dwarf and a white dwarf in this binary system, orbiting around and around each other, and material is streaming off the red giant and onto the smaller white dwarf.

This material piles up on the surface of the white dwarf forming a cosy blanket of stolen hydrogen. When the surface temperature reaches 20 million kelvin, the hydrogen begins to fuse, as if it was the core of a star. Metaphorically speaking, its skin catches fire. No, wait, even better. Its skin catches fire and then blasts off into space.

Over the course of a few months, the star brightens significantly in the sky. Sometimes a star that required a telescope before suddenly becomes visible with the unaided eye. And then it slowly fades again, back to its original brightness.

Some stars do this on a regular basis, brightening a few times a century. Others must clearly be on a longer cycle, we’ve only seen them do it once.

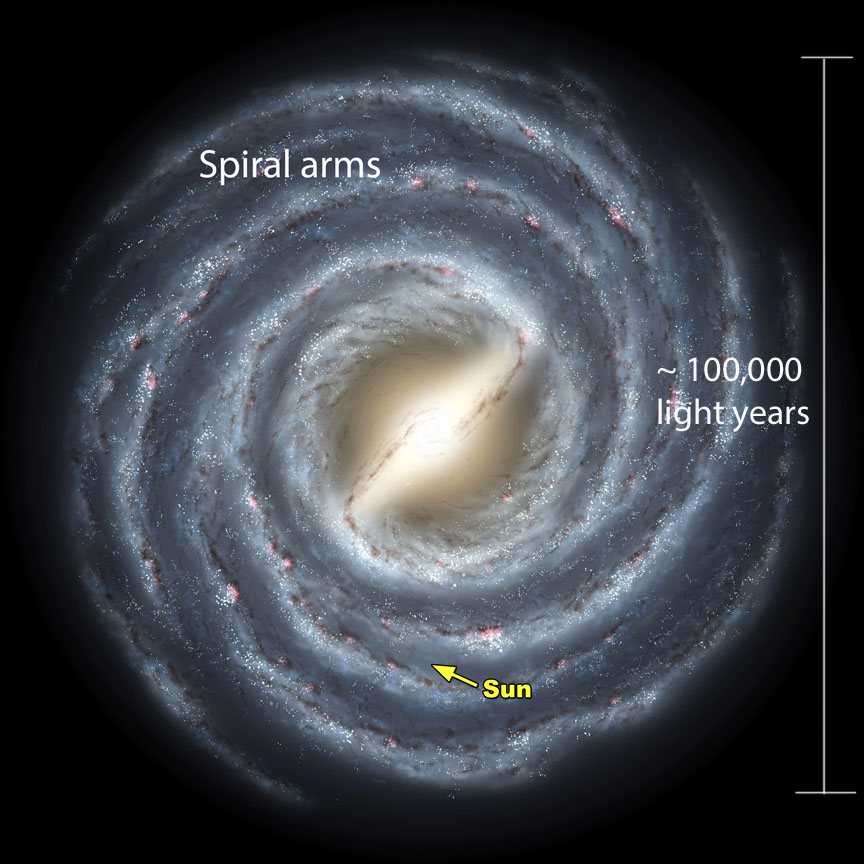

Astronomers think there are about 40 novae a year across the Milky Way, and we often see them in other galaxies.

The term “nova” was first coined by the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe in 1572, when he observed a supernova with his telescope. He called it the “nova stella”, or new star, and the name stuck. Other astronomers used the term to describe any star that brightened up in the sky, before they even really understood the causes.

During a nova event, only about 5% of the material gathered on the white dwarf is actually consumed in the flash of fusion. Some is blasted off into space, and some of the byproducts of fusion pile up on its surface.

Over millions of years, the white dwarf can collect enough material that carbon fusion can occur. At 1.4 times the mass of the Sun, a runaway fusion reaction overtakes the entire white dwarf star, releasing enough energy to detonate it in a matter of seconds.

If a regular nova is a quick flare-up of fusion on the surface of a white dwarf star, then this event is a super nova, where the entire star explodes from a runaway fusion reaction.

You might have guessed, this is known as a Type 1a supernova, and astronomers use these explosions as a way to measure distance in the Universe, because they always explode with the same amount of energy.

Hmm, I guess the terminology isn’t so bad after all: nova is a flare up, and a supernova is a catastrophic flare up to death… that works.

Now you know. A nova occurs when a dead star steals material from a binary companion, and undergoes a momentary return to the good old days of fusion. A Type Ia supernova is that final explosion when a white dwarf has gathered its last meal.