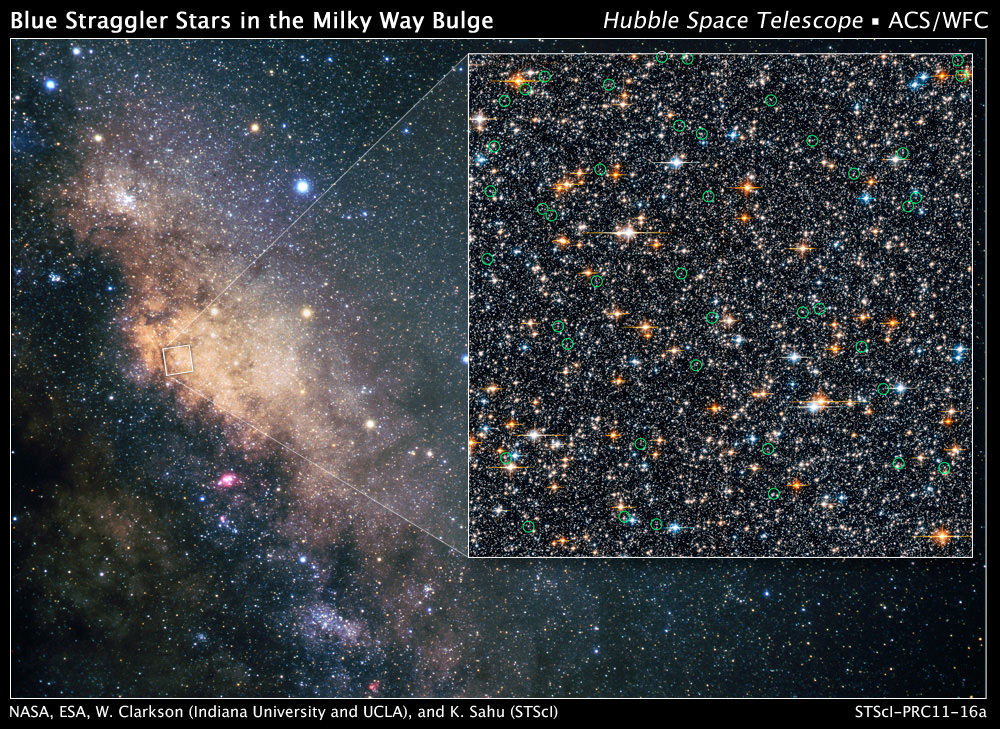

[/caption]

Globular clusters are generally some of the oldest structures in our galaxy. Many of the most famous ones formed around the same time as our galaxy, some 13 billion years ago. However, some are distinctly younger. While many classification schemes are used, one breaks globular clusters into three groups: an old halo group which includes the oldest of the clusters, those in the disk and bulge of the galaxy which tend to have higher metallicity, and a younger population of halo clusters. The latter of these provides a bit of a problem since the galaxy should have settled into a disk by the time they formed, depriving them of the necessary materials to form in the first place. But a new study suggests a solution that’s not of this galaxy.

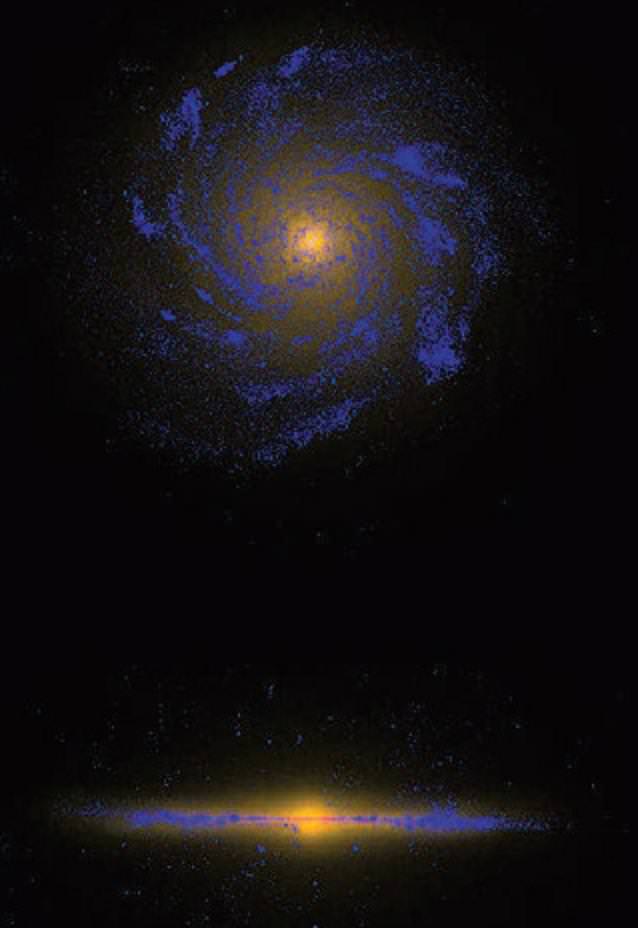

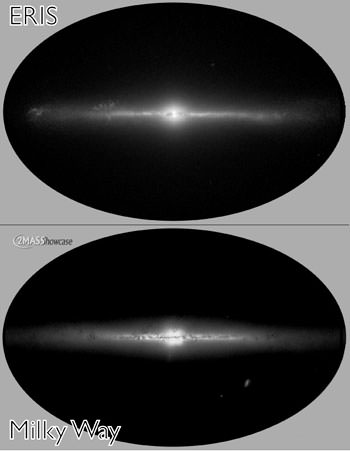

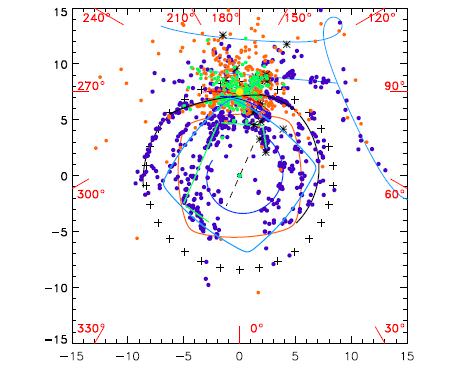

The new study looked at the distribution of these younger clusters around our Milky Way. Of the three classifications for globular clusters discussed, the young halo clusters are scattered well beyond the range of the other populations. The young halo extends to as much as 120 kiloparsecs (400 thousand light years) while the old halo clusters tend to lie within 30 kiloparsecs (100 thousand light years). Additionally, the young clusters don’t appear to be rotating with the disk of the galaxy whereas the old halo slowly orbits in the same direction as the disk.

In looking more carefully at the positions of these satellites, the team, led by Stefan Keller at the Australian National University, found that the younger population tends to lie in a wide plane that is tilted from the rotational axis of our galaxy by a mere 8°.

This plane is strikingly similar to another recognized grouping of objects: Many of the known dwarf galaxies lie in a nearly identical plane, known as the Plane of Satellites (PoS). This finding suggests that this population of globular clusters is a relic of cannibalized galaxies. Even more interesting is that, while these objects are younger than the distinctly “old” population, there is still a large variation in their ages. This implies that this plane wasn’t created by the accretion of one, or even a few minor galaxies, but a consistent feeding of small galaxies onto the Milky Way for much of the history of the universe, and all from the same direction. Studies of the distribution of satellites around our nearest major neighbor, M31, the Andromeda galaxy, has turned up a similar preferred plane, tilted some 59° from its disk.

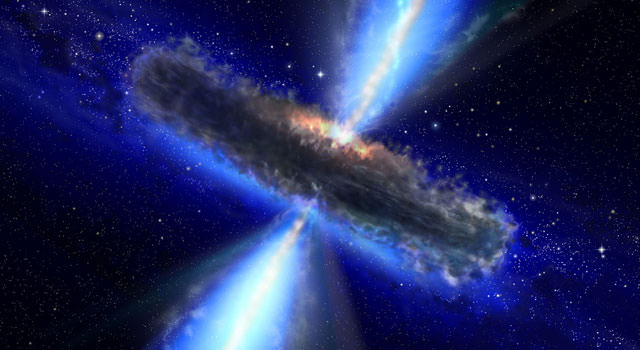

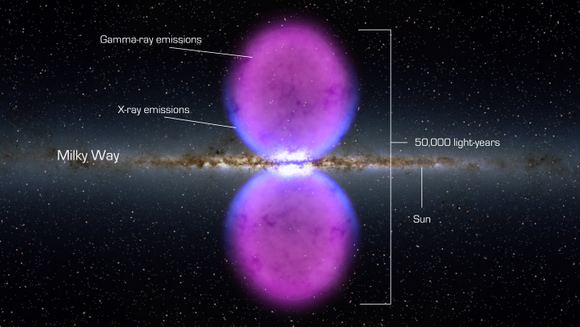

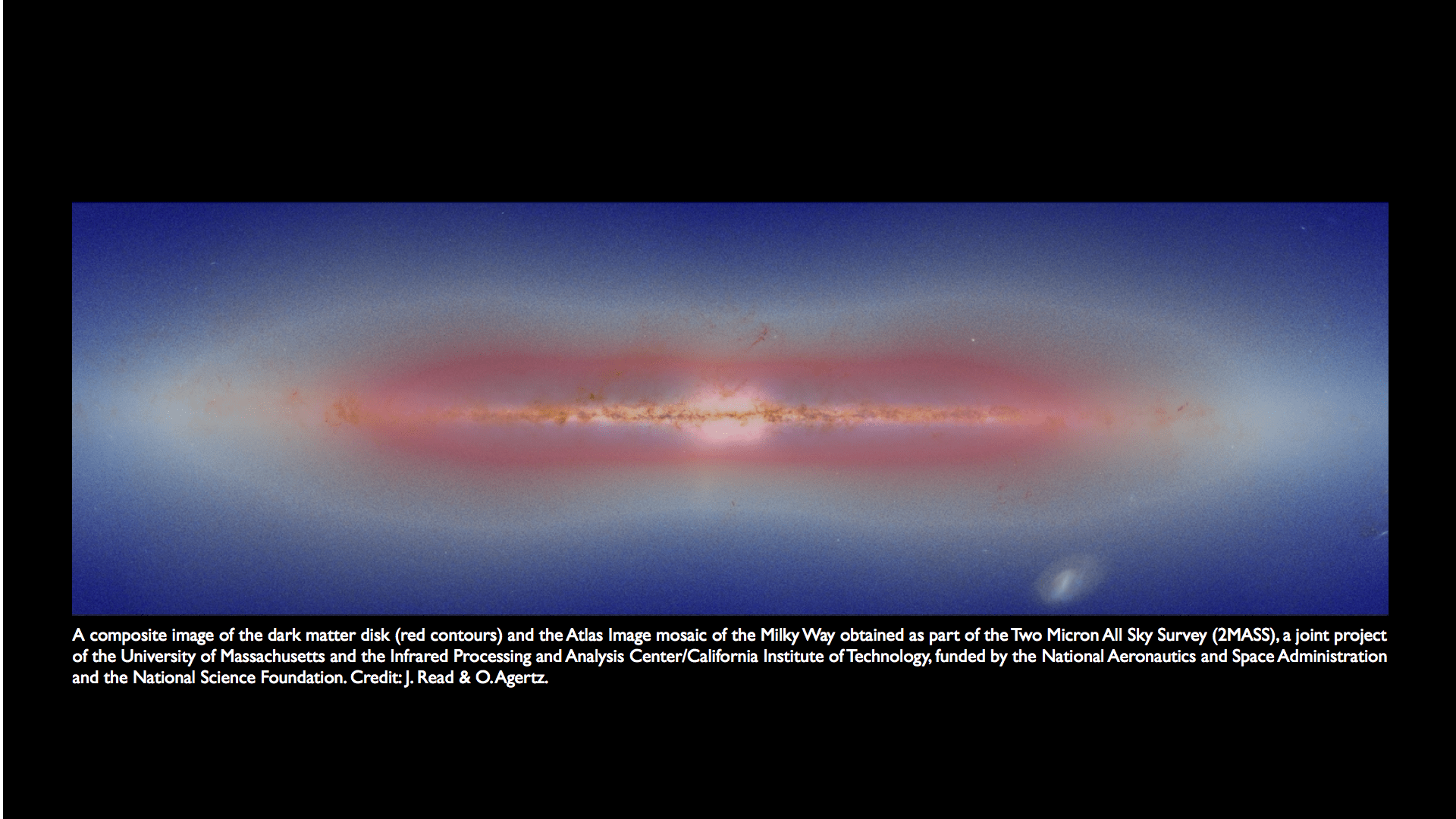

One explanation for this is that this is a preferred direction that traces invisible filaments of dark matter. While dark matter distributions are difficult to predict, models haven’t accounted for such strong filamentary structure on such small scales. Rather, in the neighborhood of our galaxy, the overall distribution is described as an oblate spheroid. One of the reasons astronomers believe our own dark matter halo is so nicely shaped is the way it is affecting the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy which is slowly being accreted onto our own. If the dark matter were more wispy, it should be stretched out in different manners.

Another possibility the authors consider is that the objects were created in a preferred plane “from the break up of a large progenitor at early times”. In other words, the filament could be a fossil of larger structure before our galaxy formed along which these dwarf galaxies formed and from which these galaxies could have been slowly accreting over the history of the galaxy.