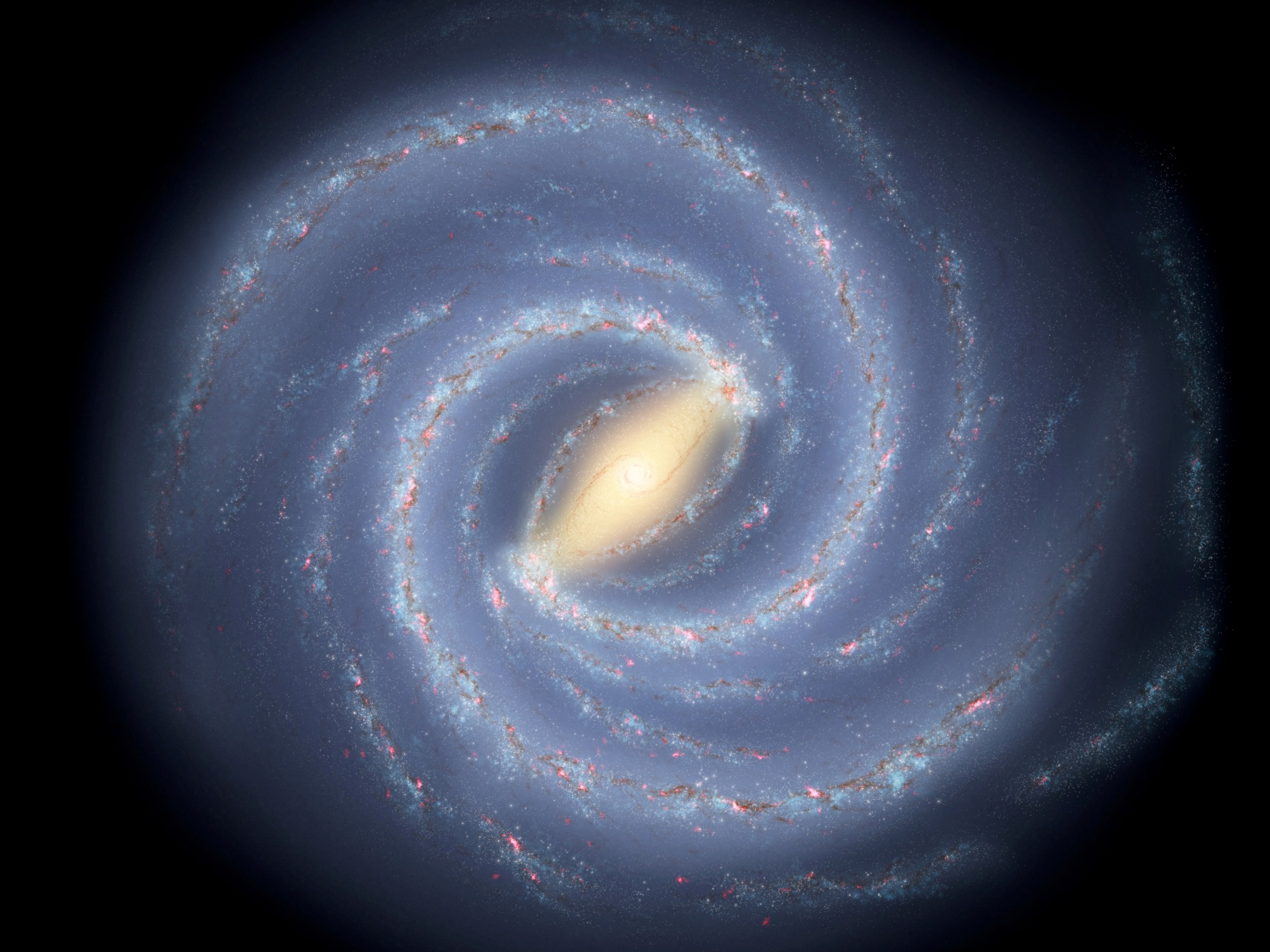

If you are not an astronomy enthusiast you not have thought much about what galaxy do we live in. So depending on that the answer may surprise you. If you know anything about galaxies you know that they are groupings of stars that number in the hundreds of billions. The most famous is the Milky Way. It is from this galaxy that we even have the term. The simple point is that the Earth is part of the Milky Way even though if we see it in the sky it looks like we are observing it from the outside. Why is that? To understand you need to know exactly where we live in neighborhood of the Milky Way Galaxy.

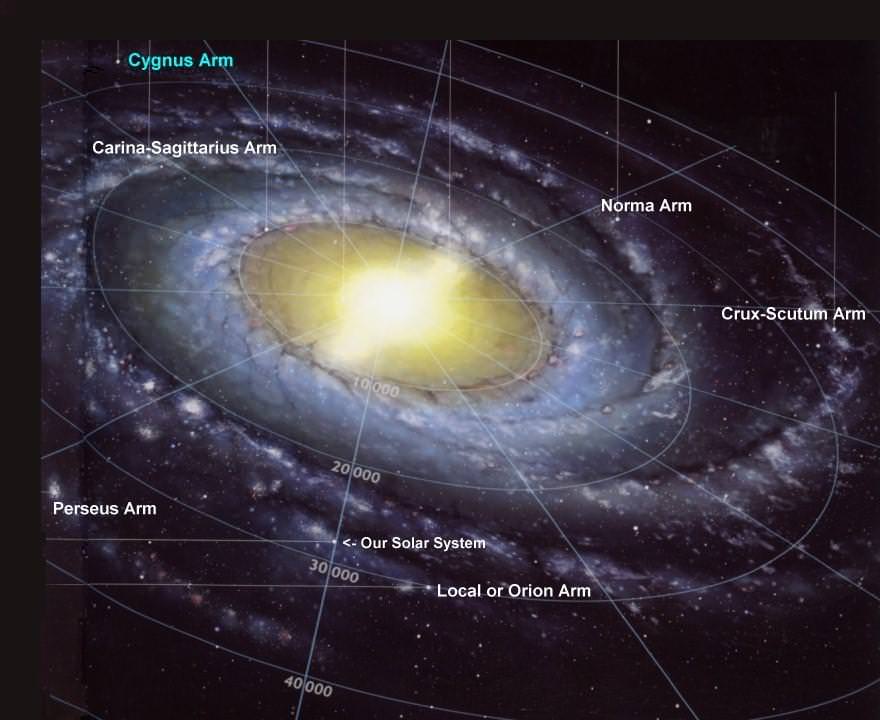

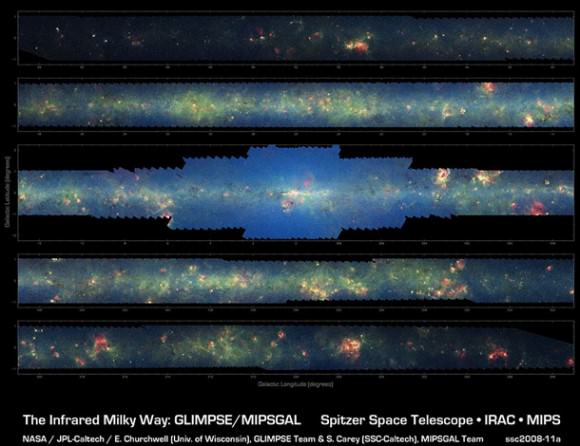

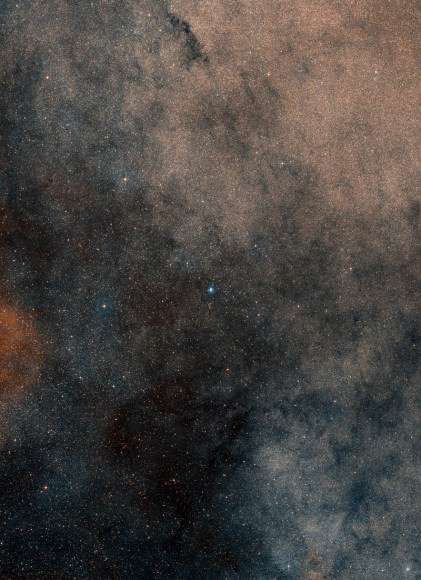

As we are part of the solar system Earth pretty much follows the path of the sun as it goes through its own orbit around the galaxy. The Milky Way is a spiral galaxy type so it has arms sort of like an octopus. The Sun is located near the outward tip of the Sagittarius arm of the Milky Way. This makes Earth about 28,000 light years from the galactic core of our home galaxy.

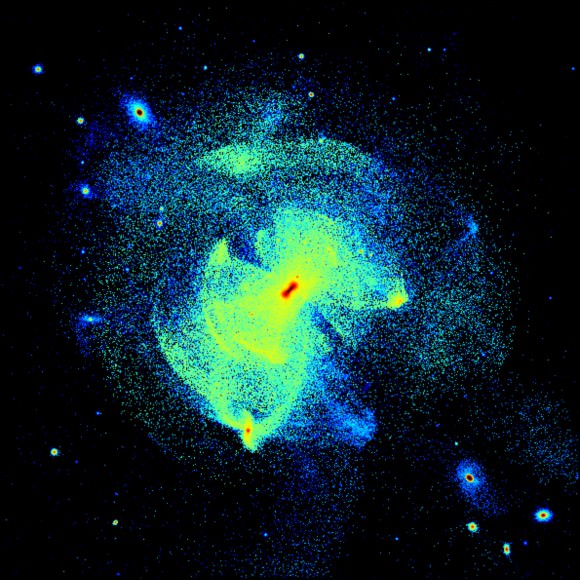

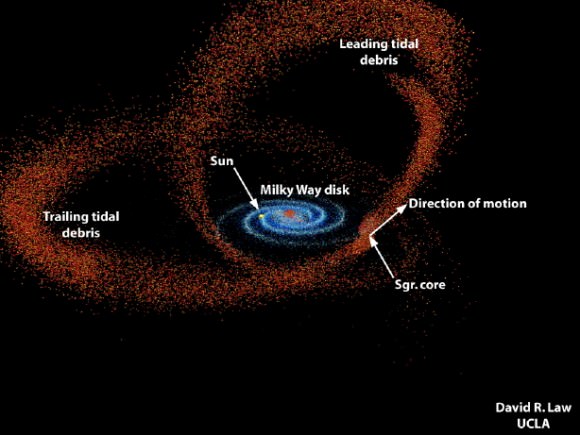

The Solar System also has a galactic year that it follows. It takes around 200 million to 250 million years for the solar system to orbit the Sun. Another indicator of our position is where the galactic equator. While our star system is considered to be on the outskirts of the Milky Way this is only an estimate. It is believed that the Milky Way is larger than first estimated. There is also suspicion that our galaxy is in the process of absorbing other smaller galaxies. However, there is not enough empirical evidence available to support the claim.

So what would be so important about knowing what part of the galaxy we live in? One reason is space exploration. Some time in the future mankind may find a way to achieve faster than light space travel. This can provide a new set of challenges for engineers and astronomers to tackle. For example how would an astronaut keep from getting lost in space? Detailed mapping and computer programming in the future could help galactic wayfarers know where they are going and more importantly how to get home.

The other reason is that it never hurts to know our place in the scheme of things. Just thinking of the challenge of finding earth if we were so far way helps us to understand how truly vast the universe is.

We have written many articles about the Milky Way galaxy for Universe Today. Here are some facts about the Milky Way, and here’s an article about the closest galaxy to the Milky Way.

If you’d like more info on galaxies, check out Hubblesite’s News Releases on Galaxies, and here’s NASA’s Science Page on Galaxies.

We’ve also recorded an episode of Astronomy Cast about galaxies. Listen here, Episode 97: Galaxies.

Sources: SEDS, Daily Galaxy