[/caption]

When our Sun begins to die, it will become a red giant as it runs out of hydrogen fuel at its core. Astronomers have a pretty good idea of what will transpire: the sun will swell to a size so large that it will swallow every planet out to Mars in our solar system. Don’t worry, though, this won’t happen for another 5 billion years. But now, astronomers have been able to watch in detail the death of a sun-like star about 550 light-years from Earth to get a better grasp on what the end might be for our Sun. The star, Chi Cygni, has swollen in size, and is now writhing in its death throes. The star has begun to pulse dramatically in and out, beating like a giant heart. New close-up photos of the surface of this distant star show its throbbing motions in unprecedented detail.

“This work opens a window onto the fate of our Sun five billion years from now, when it will near the end of its life,” said Sylvestre Lacour of the Observatoire de Paris, who led a team of astronomers studying Chi Cygni.

The scientists compared the star to a car running out of gas. The “engine” begins to sputter and pulse. On Chi Cygni, the sputterings show up as a brightening and dimming, caused by the star’s contraction and expansion.

For the first time, astronomers have photographed these dramatic changes in detail.

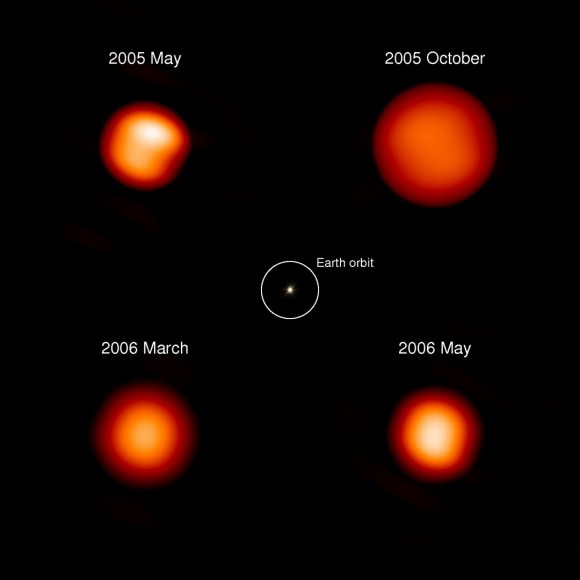

“We have essentially created an animation of a pulsating star using real images,” stated Lacour. “Our observations show that the pulsation is not only radial, but comes with inhomogeneities, like the giant hotspot that appeared at minimum radius.”

Click here to watch the animation.

Stars at this life stage are known as Mira variables. As it pulses, the star is puffing off its outer layers, which in a few hundred thousand years will create a beautifully gleaming planetary nebula.

Chi Cygni pulses once every 408 days. At its smallest diameter of 300 million miles, it becomes mottled with brilliant spots as massive plumes of hot plasma roil its surface, like the granules seen on our Sun’s surface, but much larger. As it expands, Chi Cygni cools and dims, growing to a diameter of 480 million miles – large enough to engulf and cook our solar system’s asteroid belt.

Imaging variable stars is an extremely difficult task. First, Mira variables hide within a compact and dense shell of dust and molecules. To study the stellar surface within the shell, astronomers need to observe the stars in infrared light, which allows them to see through the shell of molecules and dust, like X-rays enable physicians to see bones within the human body.

Secondly, these stars are very far away, and thus appear very small. Even though they are huge compared to the Sun, the distance makes them appear no larger than a small house on the moon as seen from Earth. Traditional telescopes lack the proper resolution. Consequently, the team turned to a technique called interferometry, which involves combining the light coming from several telescopes to yield resolution equivalent to a telescope as large as the distance between them.

They used the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory’s Infrared Optical Telescope Array, or IOTA, which was located at Whipple Observatory on Mount Hopkins, Arizona.

“IOTA offered unique capabilities,” said co-author Marc Lacasse of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA). “It allowed us to see details in the images which are about 15 times smaller than can be resolved in images from the Hubble Space Telescope.”

The team also acknowledged the usefulness of the many observations contributed annually by amateur astronomers worldwide, which were provided by the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO).

In the forthcoming decade, the prospect of ultra-sharp imaging enabled by interferometry excites astronomers. Objects that, until now, appeared point-like are progressively revealing their true nature. Stellar surfaces, black hole accretion disks, and planet forming regions surrounding newborn stars all used to be understood primarily through models. Interferometry promises to reveal their true identities and, with them, some surprises.

The new observations of Chi Cygni are reported in the December 10 issue of The Astrophysical Journal.