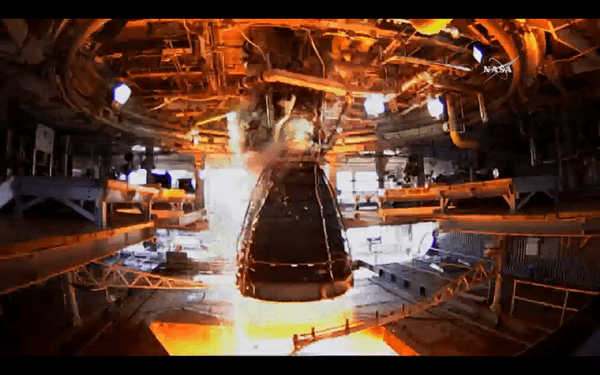

During a 535-second test on August 13, 2015, operators ran the Space Launch System (SLS) RS-25 rocket engine through a series of tests at different power levels to collect engine performance data on the A-1 test stand at NASA’s Stennis Space Center near Bay St. Louis, Mississippi. Credit: NASA

Story/imagery updated

See video below of full duration hot-fire test[/caption]

With today’s (Aug. 13) successful test firing of an RS-25 main stage engine for NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) monster rocket currently under development, the program passed a key milestone advancing the agency on the path to propel astronauts back to deep space at the turn of the decade.

The 535 second long test firing of the RS-25 development engine was conducted on the A-1 test stand at NASA’s Stennis Space Center near Bay St. Louis, Mississippi – and ran for the planned full duration of nearly 9 minutes, matching the time they will fire during an actual SLS launch.

All indications are that the hot fire test apparently went off without a hitch, on first look.

“We ran the full duration and met all test objectives,” said Steve Wofford, SLS engine manager, on NASA TV following today’s’ test firing.

“There were no anomalies.” – based on the initial look.

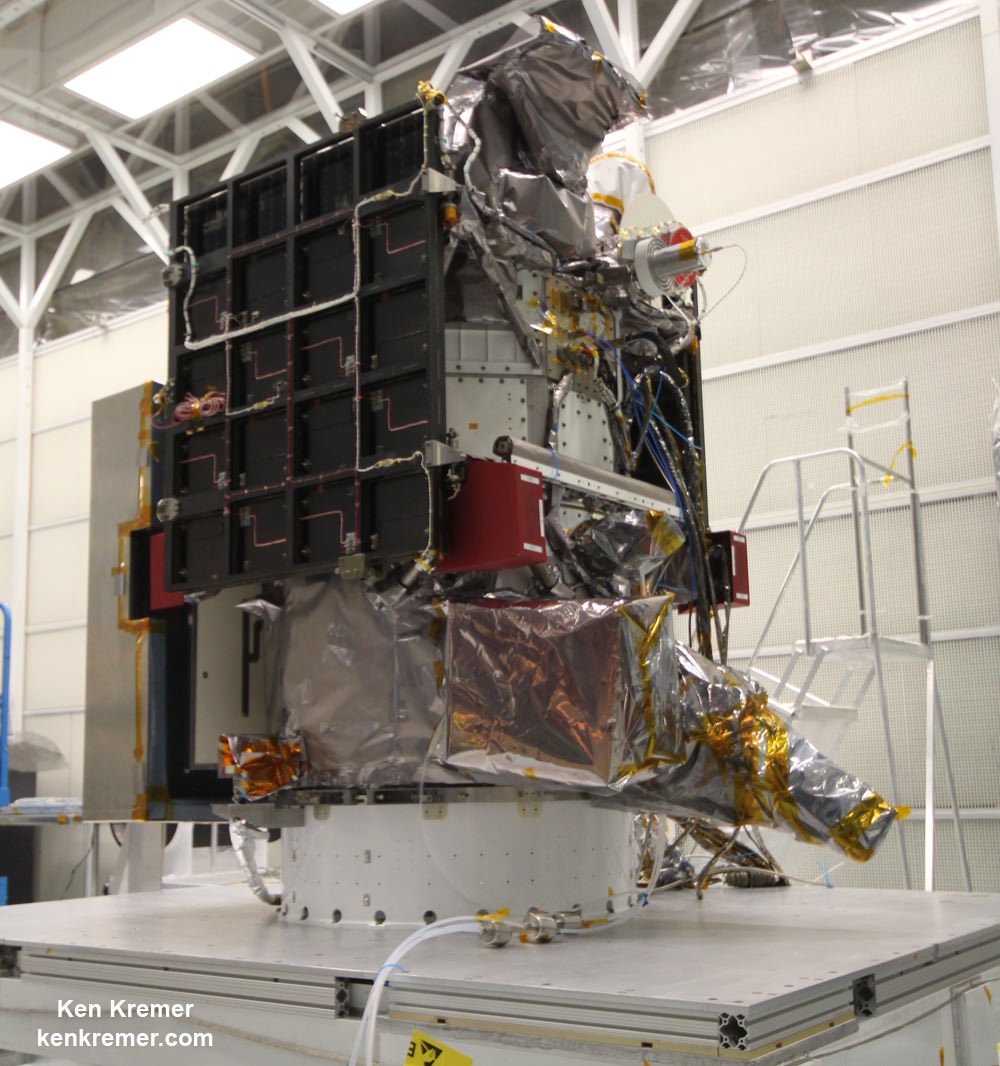

The RS-25 is actually an upgraded version of former space shuttle main engines that were used with a 100% success rate during NASA’s three decade-long Space Shuttle program to propel the now retired shuttle orbiters to low Earth orbit. Those same engines are now being modified for use by the SLS.

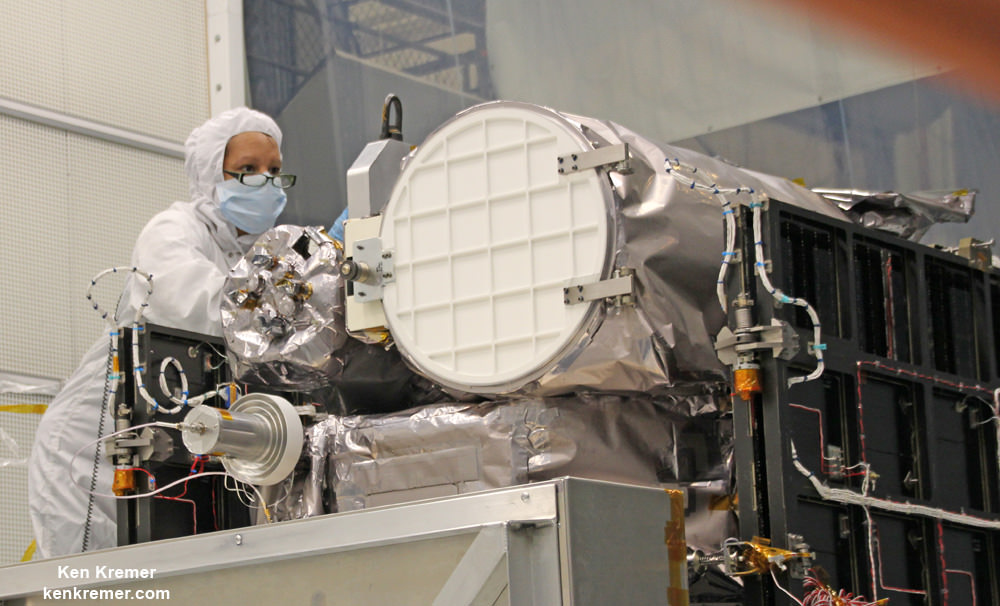

“Data collected on performance of the engine at the various power levels will aid in adapting the former space shuttle engines to the new SLS vehicle mission requirements, including development of an all-new engine controller and software,” according to NASA officials .

The engine controller functions as the “brain” of the engine, which checks engine status, maintains communication between the vehicle and the engine and relays commands back and forth.

The core stage (first stage) of the SLS will be powered by four RS-25 engines and a pair of the five-segment solid rocket boosters that will generate a combined 8.4 million pounds of liftoff thrust, making it the most powerful rocket the world has ever seen.

Since shuttle orbiters were equipped with three space shuttle main engines, the use of four RS-25s on the SLS represents another significant change that also required many modifications being thoroughly evaluated as well.

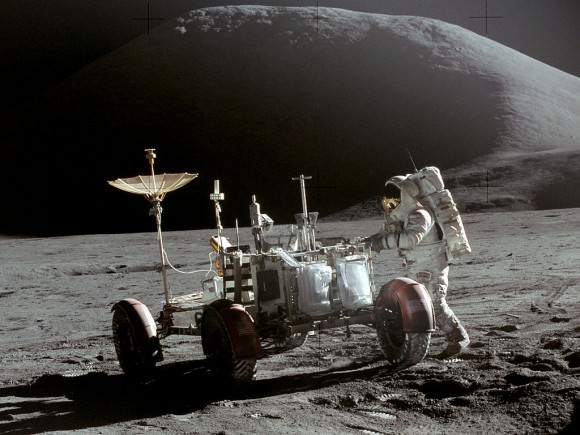

The SLS will be some 10 percent more powerful than the Saturn V rockets that propelled astronauts to the Moon, including Neil Armstrong, the human to walk on the Moon during Apollo 11 in July 1969.

SLS will loft astronauts in the Orion capsule on missions back to the Moon by around 2021, to an asteroid around 2025 and then beyond on a ‘Journey to Mars’ in the 2030s – NASA’s overriding and agency wide goal.

Each of the RS-25’s engines generates some 500,000 pounds of thrust. They are fueled by cryogenic liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen. For SLS they will be operating at 109% of power, compared to a routine usage of 104.5% during the shuttle era. They measure 14 feet tall and 8 feet in diameter.

They have to withstand and survive temperature extremes ranging from -423 degrees F to more than 6000 degrees F.

This video shows the full duration hot-fire test:

NASA has 16 of the RS-25s leftover from the shuttle era and they are all being modified and upgraded for use by the SLS rocket.

Today’s test was the sixth in a series of seven to qualify the modified engines to flight status. The engine ignited at 5:01 p.m. EDT and reached the full thrust level of 512,000 pounds within about 5 seconds.

The hot gas was exhausted out of the nozzle at 13 times the speed of sound.

Since the shuttle engines were designed and built over three decades ago, they are being modified where possible with state of the art components to enhance performance, functionality and ease of operation, by prime contractor Aerojet-Rocketdyne of Sacramento, California.

One of the key objectives of today’s engine firing and the entire hot fire series was to test the performance of a brand new engine controller assembled with modern manufacturing techniques.

“Operators on the A-1 Test Stand at Stennis are conducting the test series to qualify an all-new engine controller and put the upgraded former space shuttle main engines through the rigorous temperature and pressure conditions they will experience during a SLS mission,” says NASA.

“The new controller, or “brain,” for the engine, which monitors engine status and communicates between the vehicle and the engine, relaying commands to the engine and transmitting data back to the vehicle. The controller also provides closed-loop management of the engine by regulating the thrust and fuel mixture ratio while monitoring the engine’s health and status.’

Video caption: RS-25 – The Ferrari of Rocket Engines explained. Credit: NASA

“The RS-25 is the most complicated rocket engine out there on the market, but that’s because it’s the Ferrari of rocket engines,” says Kathryn Crowe, RS-25 propulsion engineer.

“When you’re looking at designing a rocket engine, there are several different ways you can optimize it. You can optimize it through increasing its thrust, increasing the weight to thrust ratio, or increasing its overall efficiency and how it consumes your propellant. With this engine, they maximized all three.”

Engineers will now pour over the data collected from hundreds of data channels in great detail to thoroughly analyze the test results. They will incorporate any findings into future test firings of the RS-25s.

NASA says that testing of RS-25 flight engines is set to start later this fall.

“The RS-25 engine gives SLS a proven, high performance, affordable main propulsion system for deep space exploration. It is one of the most experienced large rocket engines in the world, with more than a million seconds of ground test and flight operations time.”

NASA plans to buy completely new sets of RS-25 engines from Aerojet-Rocketdyne taking full advantage of technological advances and modern manufacturing techniques as well as lessons learned from this hot fire series of engine tests.

The maiden test flight of the SLS is targeted for no later than November 2018 and will be configured in its initial 70-metric-ton (77-ton) version with a liftoff thrust of 8.4 million pounds. It will boost an unmanned Orion on an approximately three week long test flight beyond the Moon and back.

NASA plans to gradually upgrade the SLS to achieve an unprecedented lift capability of 130 metric tons (143 tons), enabling the more distant missions even farther into our solar system.

The first SLS test flight with the uncrewed Orion is called Exploration Mission-1 (EM-1) and will launch from Launch Complex 39-B at the Kennedy Space Center.

Orion’s inaugural mission dubbed Exploration Flight Test-1 (EFT) was successfully launched on a flawless flight on Dec. 5, 2014 atop a United Launch Alliance Delta IV Heavy rocket Space Launch Complex 37 (SLC-37) at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and Planetary science and human spaceflight news.

![Plaque Commemorating the Designation of Camp Evans as a National Historic Landmark. April 2, 2015. [photo: Robert Raia Photography]](https://www.stemmingthetide.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/NHL-Plaque-Rob.jpg)

![SCR-271 Bedspring RADAR Antenna Pointing at the Moon [photo: David Mofenson; InfoAge website]](https://www.stemmingthetide.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/d-i-030-David-Mofenson.jpg)

![60-Meter Parabolic Dish Being Constructed on Project Diana Site [photo: Frank Vosk; InfoAge website]](https://www.stemmingthetide.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Dish-Assembly-1-w-Frank-Vosk.jpg)

![President Eisenhower and NASA Administrator Glennan Viewing the First Satellite Images from TIROS I. [photo: wikimedia commons]](https://www.stemmingthetide.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/President_Eisenhower_and_NASA_Administrator_Glennan_examine_photographs_taken_by_TIROS-1.jpg)

![The TIROS Dish as it Appears Today [photo: Nancy J. Graziano]](https://www.stemmingthetide.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/TIROS-Dish-Today-njg-680x1024.jpg)

![The Control Console Today. [photo: Nancy J. Graziano]](https://www.stemmingthetide.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Control-Console-njg-1024x680.jpg)

![Visitor Center Floorplan [credit: InfoAge]](https://www.stemmingthetide.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Floorplan-1024x897.jpg)