One day – and it really is only matter of time – humans will set foot on the surfaces of other far-flung worlds in our Solar System, leaving the Earth and Moon far behind to wander the valleys of Mars, trek across the ice of Europa, and perhaps even soar through the skies of Titan like winged creatures from ancient legends. But until then we must rely on the exploration of our robotic emissaries and our own boundless imagination and curiosity to picture what such voyages would be like. Here in “Wanderers,” video artist Erik Wernquist has used both resources in abundance to visualize fascinating off-world adventures yet to be undertaken by generations to come.

Continue reading “This Short Film is a Stunning Preview of Human Space Exploration”

Africa’s First Mission to the Moon Announced

Africa is home to 7 out of 10 of the world’s fastest-growing economies. It’s population is also the “youngest” in the world, with 50% of the population being 19 years old or younger. And amongst these young people are scores of innovators and entrepreneurs who are looking to bring homegrown innovation to their continent and share it with the outside world.

Nowhere is this more apparent than with the #Africa2Moon Mission, a crowdfunded campaign that aims to send a lander or orbiter to the Moon in the coming years.

Spearheaded by the Foundation for Space Development – a non-profit organization headquartered in Capetown, South Africa – the goal of this project is to fund the development of a robotic craft that will either land on or establish orbit around the Moon. Once there, it will transmit video images back to Earth, and then distribute them via the internet into classrooms all across Africa.

In so doing, the project’s founders and participants hope to help the current generation of Africans realize their own potential. Or, as it says on their website: “The #Africa2Moon Mission will inspire the youth of Africa to believe that ‘We Can Reach for the Moon’ by really reaching for the moon!”

Through their crowdfunding and a social media campaign (Twitter hashtag #Africa2Moon) they hope to raise a minimum of $150,000 for Phase I, which will consist of developing the mission concept and associated feasibility study. This mission concept will be developed collaboratively by experts assembled from African universities and industries, as well as international space experts, all under the leadership of the Mission Administrator – Professor Martinez.

Martinez is a veteran when it comes to space affairs. In addition to being the convener for the space studies program at the University of Cape Town, he is also the Chairman of the South African Council for Space Affairs (the national regulatory body for space activities in South Africa). He is joined by Jonathan Weltman, the Project Administrator, who is both an aeronautical engineer and the current CEO of the Foundation for Space Development.

Phase I is planned to run from Jan to Nov 2015 and will be the starting point for Phase II of #Africa2Moon, which will be a detailed mission design. At this point, the #Africa2Moon mission planners and engineering team will determine precisely what will be needed to see it through to completion and to reach the Moon.

Beyond inspiring young minds, the program also aims to promote education in the four major fields of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (aka STEM). Towards this end, they have pledged to commit 25% of all the funds they raise towards STEM education through a series of #Africa2Moon workshops for educators and students. In addition, numerous public engagement activities will be mounted in partnership with other groups committed to STEM education, science awareness, and outreach.

Africa is so often thought of as a land in turmoil – a place that is perennially plagued by ethnic violence, dictators, disease, drought, and famine. This popular misconception belies very positive facts about the growing economy of world’s second-largest and second-most populous continent.

That being said, all those working on the #Africa2Moon project hope it will enable future generations of Africans to bridge the humanitarian and economic divide and end Africa’s financial dependence on the rest of the world. It is also hoped that the mission will provide a platform for one or more scientific experiments, contribute to humankind’s knowledge of the moon, and form part of Africa’s contribution to global space exploration activities.

The project’s current list of supporters include the SpaceLab at the University of Cape Town, The South African Space Association, Women in Aerospace Africa, The Cape Town Science Centre, Space Commercial Services Group, Space Advisory Company, and the Space Engineering Academy. They have also launched a seed-funding campaign drive through its partnership with the UN Foundation’s #GivingTuesday initiative.

For more information, go to the Foundation’s website, or check out the mission’s Indiegogo or CauseVox page.

Further Reading: Foundation for Space Development

Weekly Space Hangout – Nov. 21, 2014: New Images of Europa

Host: Fraser Cain (@fcain)

Guests:

Morgan Rehnberg (cosmicchatter.org / @cosmic_chatter)

Brian Koberlein (@briankoberlein)

Ramin Skibba (@raminskibba)

Dave Dickinson (@astroguyz / www.astroguyz.com)

Continue reading “Weekly Space Hangout – Nov. 21, 2014: New Images of Europa”

Why Doesn’t The Sun Steal The Moon?

The Sun has so much more mass than the Earth. So, so, so much more mass. Almost everything in the Solar System is orbiting the Sun, and yet, the Moon refuses to leave our side. What gives?

The Sun contains 99.8% of the entire mass of the Solar System. It looks to us like everything seems to orbit the Sun, so why doesn’t the Sun capture the Moon from Earth like a schoolyard bully snatching the Earth’s lunch money. That would make sense right? It all fits in with our skewed view of social hierarchy based on an entities volume.

Good news! It’s already happened, In a way. The Sun has already captured the Moon. If you look at the orbit of the Moon, it orbits the Sun similar to the way Earth does. Normally the motion of the Moon around the Sun is drawn as a kind of Spirograph pattern, but its actual motion is basically the same orbit as Earth with a small wobble to it.

The Moon also orbits the Earth. You might think this is because the Earth is much closer to the Moon than the Sun. After all, the strength of gravity depends not only on the mass of an object, but also on its distance from you. But this isn’t the case. The Sun is about 400 times more distant from the Moon than the Earth, but the Sun is about 330,000 times more massive.

If you’re up for some napkin calculations, you little mathlete, by using Newton’s law of gravity, you find that even with its greater distance, the Sun pulls on the Moon about twice as hard as the Earth does.

So why can’t the Moon escape the Earth?

In order to escape the gravitational pull of a body, you need to be moving fast enough *relative to that body* to escape its pull. This is known as the escape velocity of the object.

So, yes, the Sun is totally trying to rip the Moon away from the Earth, but the Earth is super clingy.

The speed of the Moon around the Earth is about 1 km/s. At the Moon’s distance from the Earth, the escape velocity is about 1.2 km/s. The Moon simply isn’t moving fast enough to escape the Earth.

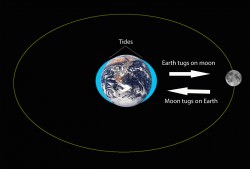

Man, those numbers sure are close. I wonder if we could kickstart a rocket to stick on the side? So, even though the Moon can’t escape the Earth, it is gradually moving away. This is due to the tidal interactions between the Earth and Moon, which we talk about another video we’ll link at the end of this one.

So even though the Moon will never escape the Earth, it will continue to move away. So, what do you think? What kind of devious project should we start to get the Moon that little boost so it finally escapes the clingy Earth and all its clingy Klingon clingyness? Tell us in the comments below.

And if you like what you see, come check out our Patreon page and find out how you can get these videos early while helping us bring you more great content!

Chinese Unmanned Lunar Orbiter Returns Home Safely, Paves Path for Ambitious Lunar Sample Return

A Chinese robotic probe has just successfully completed the first round trip to the Moon and back home in four decades that paves the path for China’s next great space leap forward – an ambitious mission to return samples from the lunar surface later this decade.

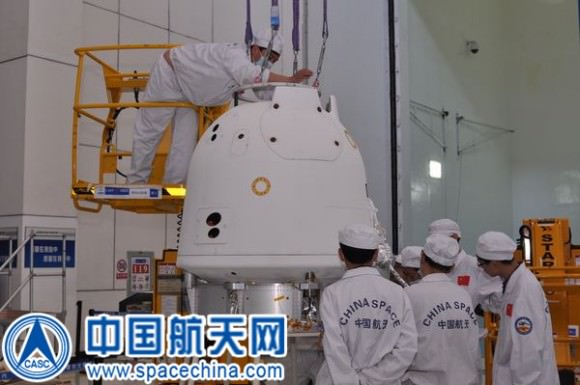

On Saturday, Nov. 1, the unmanned Chang’e-5 T1 test capsule nicknamed “Xiaofei” concluded an eight-day test flight around the Moon by safely landing in Siziwang Banner of China’s Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, according to a report by the official Xinhua News agency.

China thus become only the third nation to demonstrate lunar return technology following the former Soviet Union and the United States. The Soviet Union conducted the last lunar return mission in the 1970s.

Search teams with helicopters recovered the “Xiaofei” orbiter intact at the planned landing zone about 500 kilometers away from Beijing.

The Chang’e-5 T1 test mission is an unequivocally clear demonstration of China’s mounting technological prowess.

Chang’e-5 T1 served as a technology testbed and precursor flight for China’s planned Chang’e-5 probe, a future mission aimed at conducting China’s first lunar sample return mission in 2017.

“Chang’e-5 is expected to collect a 2-kg sample from two meters under the Moon’s surface and bring it home,” according to Wu Weiren, chief designer of China’s lunar exploration program.

The ability to gather and analyze pristine new soil and rocks samples from the Moon’s surface would be a boon for scientists worldwide seeking to unlock the mysteries of the solar system’s origin and evolution.

“Xiaofei” was launched on Oct. 23 EDT/Oct. 24 BJT atop an advanced Long March-3C rocket at 2 AM Beijing local time (BJT), 1800 GMT, from the Xichang Satellite Launch Center in China’s southwestern Sichuan Province.

It was boosted on an 840,000 kilometer, eight-day mission trajectory that swung halfway around the far side of the Moon and back. It did not enter lunar orbit.

During its path finding journey, “Xiaofei” captured incredible imagery of the Moon and Earth, eerie globes hanging together in the ocean of space.

The probe was developed by the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation. The service module is based on China’s earlier Chang’e-2 spacecraft.

On its return, the probe hit the Earth’s atmosphere at around 6:13 a.m. Saturday morning at about 11.2 kilometers per second for reentry and a parachute assisted soft landing in north China’s Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.

The goal was to test and validate guidance, navigation and control, heat shield, and trajectory design technologies required for the sample return capsule’s safe re-entry following a lunar touchdown mission and collection of soil and rock samples from the lunar surface – planned for the Chang’e-5 mission.

“To help it slow down, the craft is designed to ‘bounce’ off the edge of the atmosphere, before re-entering again. The process has been compared to a stone skipping across water, and can shorten the ‘braking distance’ for the orbiter,” according to Zhou Jianliang, chief engineer with the Beijing Aerospace Command and Control Center.

“Really, this is like braking a car,” said Zhou, “The faster you drive, the longer the distance you need to bring the car to a complete stop.”

China hopes to launch the Chang’e-5 mission in 2017 as the third step in the nation’s ambitious lunar exploration program.

The first step involved a pair of highly successful lunar orbiters named Chang’e-1 and Chang’e-2 which launched in 2007 and 2010.

The second step involved the hugely successful Chang’e-3 mothership lander and piggybacked Yutu moon rover which safely touched down on the Moon at Mare Imbrium (Sea of Rains) on Dec. 14, 2013 – marking China’s first successful spacecraft landing on an extraterrestrial body in history, and chronicled extensively in my reporting here.

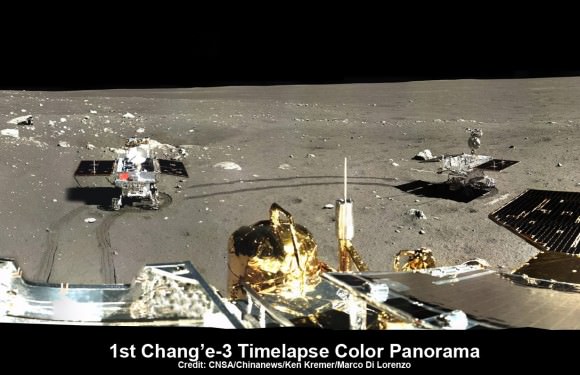

See below our time-lapse photo mosaic showing China’s Yutu rover dramatically trundling across the Moon’s stark gray terrain in the first weeks after she rolled all six wheels onto the desolate lunar plains.

The complete time-lapse mosaic shows Yutu at three different positions trekking around the landing site, and gives a real sense of how it maneuvered around on its 1st Lunar Day.

The 360 degree panoramic mosaic was created by the imaging team of scientists Ken Kremer and Marco Di Lorenzo from images captured by the color camera aboard Chang’e-3 lander and was featured at Astronomy Picture of the Day (APOD) on Feb. 3, 2014.

China’s space officials are currently evaluating whether they will proceed with launching the Chang’e-4 lunar landing mission in 2016, which was a backup probe to Chang’e-3. Although Yutu was initially successful, it encountered difficulties about a month after rolling onto the surface which prevented it from roving across the surface and accomplishing some of its science objectives.

China is pushing forward with plans to start building a manned space station later this decade and considering whether to launch astronauts to the Moon by the mid 2020s or later.

Meanwhile, as American lunar and planetary missions sit still on the drawing board thanks to visionless US politicians, China continues to forge ahead with no end in sight.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and planetary science and human spaceflight news.

Making the Moon: The Practice Crater Fields of Flagstaff, Arizona

Between the years of 1969 and 1972 the astronauts of the Apollo missions personally explored the alien landscape of the lunar surface, shuffling, bounding, digging, and roving across six sites on the Moon. In order to prepare for their off-world adventures though, they needed to practice extensively here on Earth so they would be ready to execute the long laundry lists of activities they were required to accomplish during their lunar EVAs. But where on Earth could they find the type of landscape that resembles the Moon’s rugged, dusty, and — most importantly — cratered terrain?

Enter the Cinder Lakes Crater Fields of Flagstaff, Arizona.

The Cinder Lakes Crater Fields northeast of Flagstaff, near the famous San Francisco peaks and just south of the Sunset Crater volcano, were used for Apollo-era training because of the inherently lunar-like volcanic landscape. LRV practice as well as hand tool geology and lunar morphology training were performed there, as well as ALSEP – Apollo Lunar Surface Experiment Package – placement and setup practice.

The photo above shows Apollo 15 astronauts Dave Scott and Jim Irwin driving a test LRV nicknamed Grover along the rim of a small “lunar crater.” (This particular exercise was performed on Nov. 2, 1970… 44 years ago today!)

Although the craters might look similar to the ones found on the Moon, they were actually created by the USGS in 1967 by digging holes and filling them with various amounts of explosives, which were detonated to simulate different-sized lunar impact craters. The human-made craters ranged in size from 5-40 feet (1.5-12 meters) in diameter.

The two crater field sites at Cinder Lakes were chosen because of the specific surface geology: a layer of basaltic cinders covering clay beds, left over from an eruption of the Sunset Crater volcano 950 years ago. After the explosions the excavated lighter clay material spread out from the blast craters and across the fields, like ejecta from actual meteorite impacts. A total of 497 craters were made within two sites comprising 2,000 square feet.

Detonations were done in series to simulate ejected debris from cratering events of different ages. And one of the areas of Cinder Lakes was designed to specifically replicate craters found within a particular region of the Apollo 11 Mare Tranquillitatis landing site.

Watch a contemporary educational film from the USGS showing the crater field detonations here. (HT to spaceflight archivist David S. F. Portree for the link.)

Today only the largest craters can be distinguished at all in the publicly-accessible Cinder Lakes field, which has become popular with ATV enthusiasts. But a smaller field, fenced off to vehicles, still contains many of the original craters used by Apollo astronauts, softened by time and weather but still visible.

A couple of other areas were used as lunar analogue training fields as well, such as the nearby Merriam Crater and Black Canyon fields — the latter of which is now covered by a housing development. Geology field training exercises by Apollo astronauts were also performed at locations in Texas, New Mexico, Nevada, Oregon, Alaska, Idaho, Iceland, Mexico, the Grand Canyon, and the lava fields of Hawaii. But only in Arizona were actual craters made to specifically simulate the Moon!

Read more about the Cinder Lakes Crater Field in a presentation document (my main article source) by LPI’s Dr. David Kring, and you can find more recent photos of the Crater Lakes sites on this page by LPI’s Jim Scotti.

Top photo research: J.L. Pickering. Source: The Project Apollo Image Archive.

Here’s What it Looks Like When a Refrigerator Hits the Moon

Ever wonder what your refrigerator’s impacting at the speed of a tank artillery shell would do to the Moon? The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter’s (LRO) primary camera has provided an image of just such an event when it located the impact site of another NASA spacecraft, the Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer (LADEE). The fridge-sized LADEE spacecraft completed its final Lunar orbit on April 18, 2014, and then crashed into the far side of the Moon. LADEE ground controllers were pretty certain where it crashed but no orbiter had found it until now. With billions of craters across the lunar surface, finding a fresh crater is a daunting task, but a new method of searching for fresh craters is what found LADEE.

The primary purpose of the LADEE mission was to search for lunar dust in the exceedingly thin atmosphere of the Moon. NASA Apollo astronauts had taken notes and drawings of incredible spires and rays of apparent dust above the horizon of the Moon as they were in orbit. To this day it remains a mystery although LADEE researchers are still working their data to find out more.

The LRO spacecraft has been in lunar orbit since 2007. With the LROC Narrow Angle Camera, LRO has the ability to resolve objects less than 2 feet across, and it was likely just a matter of finding time to snap and to search photos for a tiny impact crater.

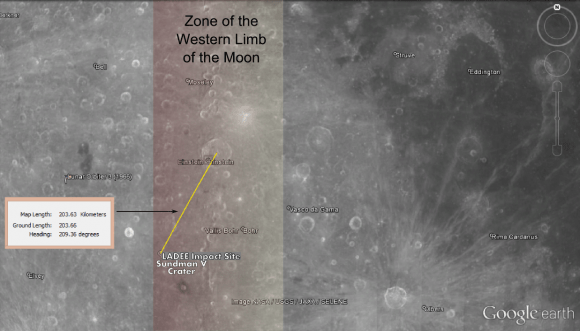

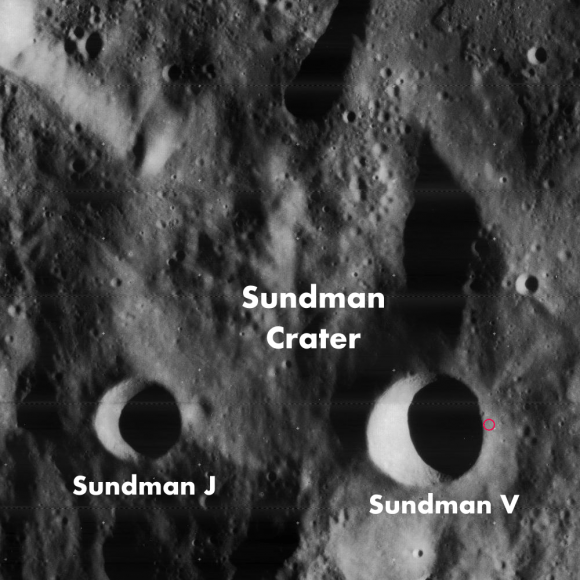

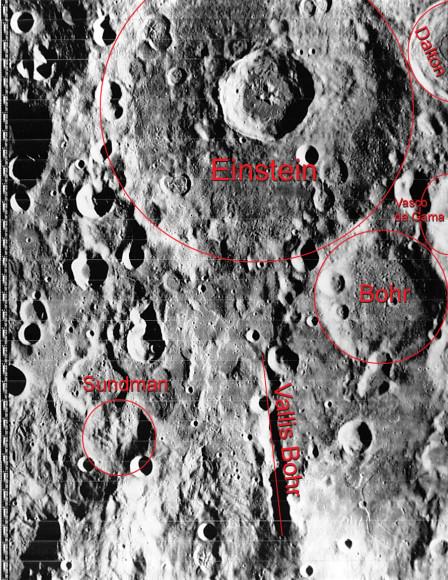

However, the LROC team recently developed a new algorithm in software to search for fresh craters. Having a good idea where to begin the search, they decided to search for LADEE and quickly found it. The LROC team said the impact site is “about half a mile (780 meters) from the Sundman V crater rim with an altitude of about 8,497 feet (2,590 meters) and was only about two tenths of a mile (300 meters) north of the location mission controllers predicted based on tracking data.” Sundman Crater is about 200 km (125 miles) from a larger crater named Einstein.

The LADEE impact site is within 300 meters of the location estimated by the LADEE team. The ground control team at Ames Research Center knew the location very well within just hours after the time of the planned impact. They had to know LADEE’s location in orbit with split-second accuracy and also know very accurately the altitude of the terrain LADEE was skimming over. LADEE was traveling at 1699 meters per second (3,800 mph, 5,574 feet/sec) upon impact.

But still, finding something as small as this crater can be difficult.

Looking at these images, the scale of lunar morphology is very deceiving. Craters that are 10 meters in diameter can be mistaken for 100 meter or even 1000 meters. The first image and third images (below) in this article are showing only a small portion of the external slope of the eastern rim of Sundman V, the satellite crater to the southeast of crater Sundman. Sundman V is 19,000 meters in diameter (19 km, 11.8 miles) whereas the first image is only 223 meters across.

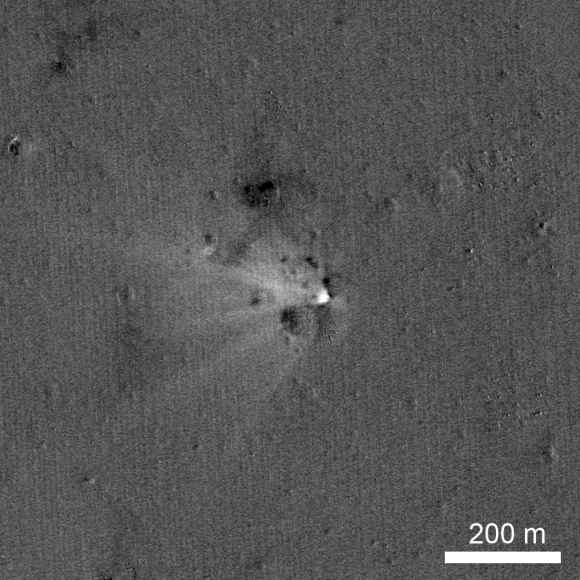

The following image, which is the ratioing of “before” and “after” impact images by LROC, clearly reveals the impact scar from LADEE. LADEE’s crater is only approximately 10 feet in diameter (3 m) with the ejecta fanning out 200 meters to the west by northwest. LADEE was traveling westward across the face of the Moon that we see from Earth, reached the western limb and finally encountered Sundman.

The discovery so close to the predicted impact site confirmed how accurately the LADEE team could model the chaotic orbits around the Moon – at least during short intervals of time. Gravitationally, the Moon is truly like Swiss cheese. The effects of upwelling magma during its creation, the effects of the Earth’s tidal forces, and all the billions of asteroid impacts created a very chaotic gravitational field. Where the lunar surface is higher or more dense, gravity is stronger and vice-versa. LADEE struggled to maintain an orbit that would not run into the Moon. Without a constant vigil by Ames engineers, LADEE’s orbit would be shifted and rotated relative to the Moon’s surface until it eventually would intersect the Lunar surface – run into the Moon. Eventually, this had to happen as LADEE ran out of propulsion fuel.

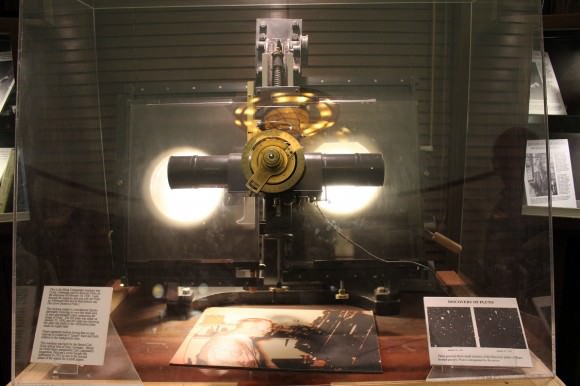

The method used by the LROC team in its basic approach is by no means new. Clyde Tombaugh used a blink comparator to search for Planet X for several months and many frame pairs of the night sky. The comparator would essentially show one image and then a second of the same view taken a few nights apart to Clyde’s eye. Tombaugh’s eye and brain could process the two images and identify slight shifts of an object from one frame to the other. Stars are essentially fixed, don’t move but objects in our solar system do move in the night sky over hours or days. In the same way, the new software employed by LROC engineers takes two images and compares them mathematically. A human is replaced by a computer and software to weed out the slightest changes between a pair of images; images of the same area but spaced in time. Finding changes on the surface of a body such as the Moon or Mars is made especially difficult because of the slightest changes in lighting and location of the observer (the spacecraft). The new LROC software marks a new step forward in sophistication and thus has returned LADEE back to us.

The following Lunar Orbiter image from the 1960s is high contrast and reveals surface relief in much more detail. Einstein crater is clearly seen, as is Sundman with J and V satellite craters on its rim.

References:

NASA’s LRO Spacecraft Captures Images of LADEE’s Impact Crater

Karl Frithiof Sundman (28 October 1873, Kaskinen – 28 September 1949, Helsinki)

China’s Lunar Test Spacecraft Takes Incredible Picture of Earth and Moon Together

The Chinese lunar test mission Chang’e 5T1 has sent back some amazing and unique views of the Moon’s far side, with the Earth joining in for a cameo in the image above. According to the crew at UnmannedSpaceflight.com the images were taken with the spacecraft’s solar array monitoring camera.

Add this marvelous shot to previous views of the Earth and Moon together.

The mission launched on October 23 and is taking an eight-day roundtrip flight around the Moon and is now journeying back to Earth. The mission is a test run for Chang’e-5, China’s fourth lunar probe that aims to gather samples from the Moon’s surface, currently set for 2017. Chang’e 5T1 will return to Earth on October 31.

The test flight orbit had a perigee of 209 kilometers and reached an apogee of about 380,000 kilometers, swinging halfway around the Moon, but did not enter lunar orbit.

See original images at Xinhua News.

H/T: Cosmic_Penguin and Unmanned Spaceflight.

Make a Deal for Land on the Moon

Whether its asteroid prospecting, mining interests, or space tourism, a lot of industries are taking aim at space exploration. Some pioneering spirits – such as Elon Musk – even believe humanity’s survival depends on our colonizing onto other planets – such as the Moon and Mars. It’s little surprise then that lunar land peddlers have begun making deals for land on the Moon.

Weekly Space Hangout – Oct. 24, 2014

Host: Fraser Cain (@fcain)

Guests:

Ramin Skibba (@raminskibba)

Continue reading “Weekly Space Hangout – Oct. 24, 2014”