China launched a robotic mission to the Moon today (Oct. 23 EDT/Oct. 24 BJT) that will test a slew of key technologies required for safely delivering samples gathered from the Moon’s surface and returning them to Earth later this decade for analysis by researchers.

Today’s unmanned launch of what has been dubbed “Chang’e-5 T1” is a technology testbed serving as a precursor for China’s planned Chang’e-5 probe, a future mission aimed at conducting China’s first lunar sample return mission in 2017.

“Chang’e-5 T1” was successfully launched atop an advanced Long March-3C rocket at 2 AM Beijing local time (BJT), 1800 GMT, from the Xichang Satellite Launch Center in China’s southwestern Sichuan Province.

“The test spacecraft separated from its carrier rocket and entered the expected the orbit shortly after the liftoff, according to the State Administration of Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense (SASTIND),” says the official Xinhua news agency. The launch was not broadcast live.

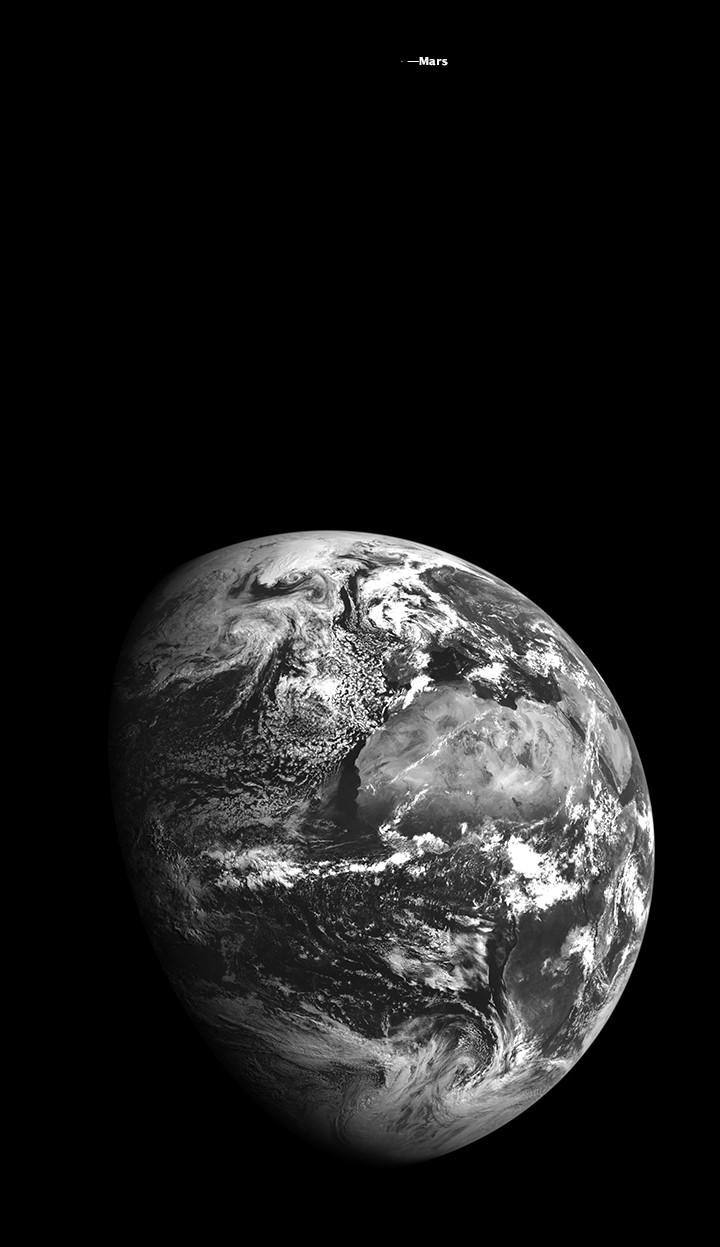

The return capsule was placed on a lunar transfer trajectory that will take it on a simple eight day roundtrip flight around the Moon and journey back to Earth. The orbit had a perigee of 209 kilometers and will reach an apogee of some 380,000 kilometers and swing halfway around the Moon, but not enter lunar orbit.

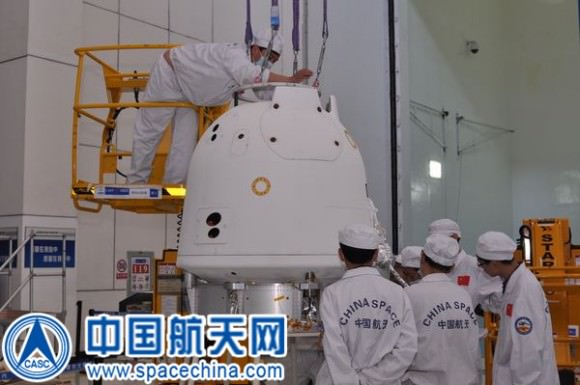

The probe was developed by the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation. The service module is based on China’s earlier Chang’e-2 spacecraft and the capsule somewhat resembles a mini-Shenzhou.

On its return, the probe will hit the Earth’s atmosphere at about 11.2 kilometers per second for reentry and a parachute assisted landing. The capsule is targeted to soft land in north China’s Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.

The goal is to test and validate guidance, navigation and control, heat shield, and trajectory design technologies required for the sample return capsule’s safe re-entry following a lunar touchdown mission and collection of soil and rock samples from the lunar surface – planned for the Chang’e-5 mission.

China hopes to launch the Chang’e-5 mission in 2017 as the third step in the nation’s ambitious lunar exploration program.

The first step involved a pair of highly successful lunar orbiters named Chang’e-1 and Chang’e-2 which launched in 2007 and 2010, respectively.

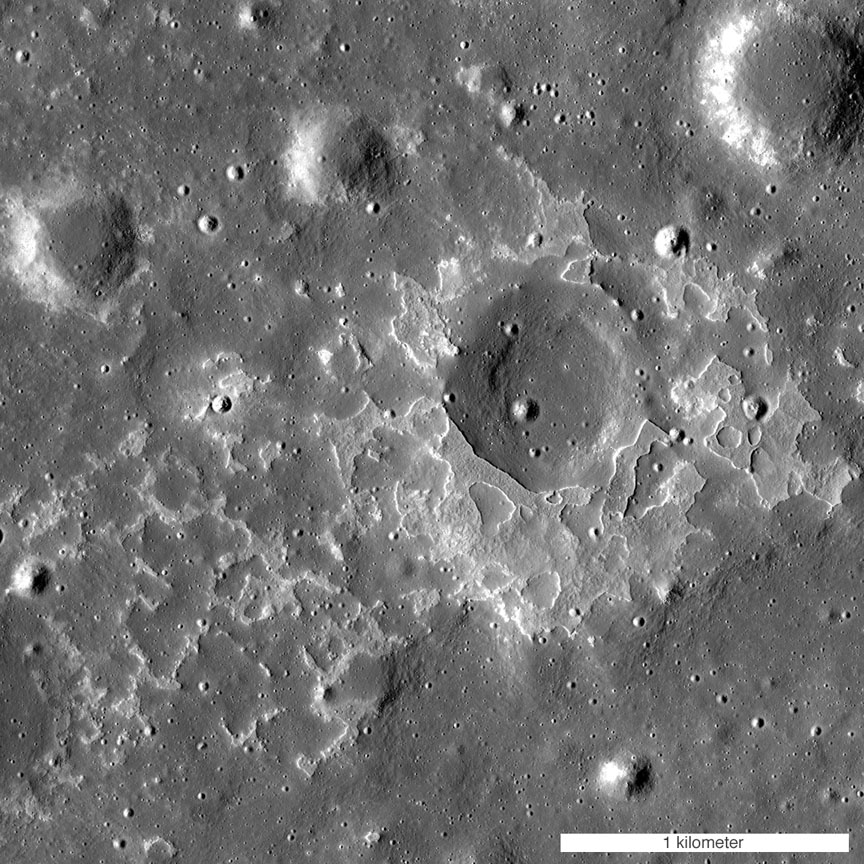

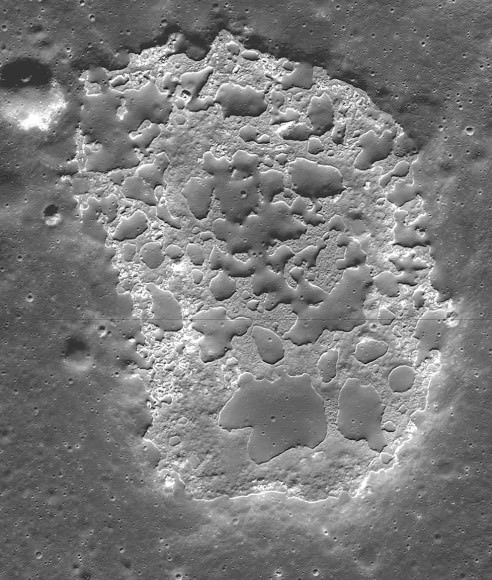

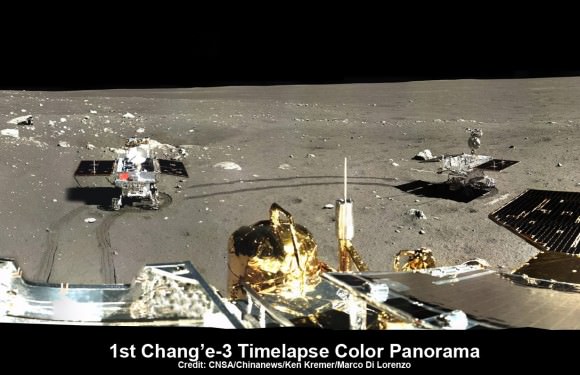

The second step involved the hugely successful Chang’e-3 mothership lander and piggybacked Yutu moon rover which safely touched down on the Moon at Mare Imbrium (Sea of Rains) on Dec. 14, 2013 – marking China’s first successful spacecraft landing on an extraterrestrial body in history, and chronicled extensively in my reporting here.

See below our time-lapse photo mosaic showing China’s Yutu rover dramatically trundling across the Moon’s stark gray terrain in the first weeks after she rolled all six wheels onto the desolate lunar plains.

The complete time-lapse mosaic shows Yutu at three different positions trekking around the landing site, and gives a real sense of how it maneuvered around on its 1st Lunar Day.

The 360 degree panoramic mosaic was created by the imaging team of scientists Ken Kremer and Marco Di Lorenzo from images captured by the color camera aboard Chang’e-3 lander and was featured at Astronomy Picture of the Day (APOD) on Feb. 3, 2014.

Although Yutu was initially very successful, it encountered difficulties about six weeks after rolling onto the surface which prevented it from roving further across the surface and accomplishing some of its science objectives.

China’s space officials are currently evaluating whether they will proceed with launching the Chang’e-4 lunar landing mission in 2016, which was a backup probe to Chang’e-3.

China is pushing forward with plans to start building a manned space station later this decade and considering whether to launch astronauts to the Moon by the mid 2020s or later.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and planetary science and human spaceflight news.

…………….

Learn more about NASA Human and Robotic Spaceflight at Ken’s upcoming presentations:

Oct 26/27: “Antares/Cygnus ISS Rocket Launch from Virginia”; Rodeway Inn, Chincoteague, VA