Are we perhaps one step closer to being able to live on the Moon? A new device developed by scientists in Cambridge, UK, can extract oxygen from Moon rock. This technology would be extremely important for creating a lunar bases for long term habitation, or using the Moon as a jump-off point to explore the deeper reaches of space.

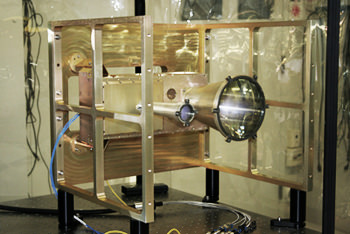

The new device, a reactor developed by Derek Fray and his colleagues, was created from a modified electrochemical process the team invented in 2000 to get metals and alloys from metal oxides. The process uses the oxides — also found in Moon rocks — as a cathode, together with an anode made of carbon. To get the current flowing through the system, the electrodes sit in an electrolyte solution of molten calcium chloride (CaCl2), a common salt with a melting point of almost 800 °C.

The current strips the metal oxide pellets of oxygen atoms, which are ionized and dissolve in the molten salt. The negatively charged oxygen ions move through the molten salt to the anode where they give up their extra electrons and react with the carbon to produce carbon dioxide — a process that erodes the anode. Meanwhile, pure metal is formed over at the cathode.

To make the system produce oxygen and not carbon dioxide, Fray had to make an unreactive anode. “Without those anodes, it doesn’t work,” said Fray. He discovered that calcium titanate, which is a poor electrical conductor on its own, became a much better conductor when he added some calcium ruthenate to it. This mixture produced an anode that barely erodes at all — after running the reactor for 150 hours, Fray calculated that the anode would wear away by roughly three centimeters a year.

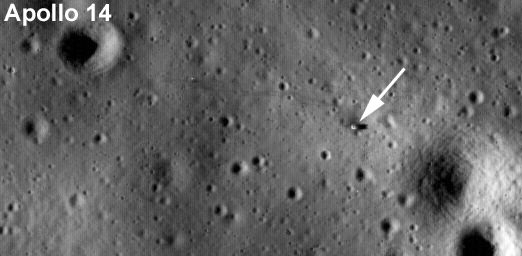

To heat the reactor on the Moon would need just a small amount of power, Fray said, and the reactor itself can be thermally insulated to lock heat in. The three reactors would need about 4.5 kilowatts of power, which could be supplied by solar panels or even a small nuclear reactor placed on the Moon.

In their tests, Fray and his team used a simulated lunar rock called JSC-1, developed by NASA. Fray anticipates that three reactors, each a meter high, would be enough to generate a ton of oxygen per year on the Moon. Three tons of rock are needed to produce a ton of oxygen, and in tests the team saw almost 100% recovery of oxygen, he says. Fray presented the results last week at the Congress of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry in Glasgow, UK.

Source: Nature