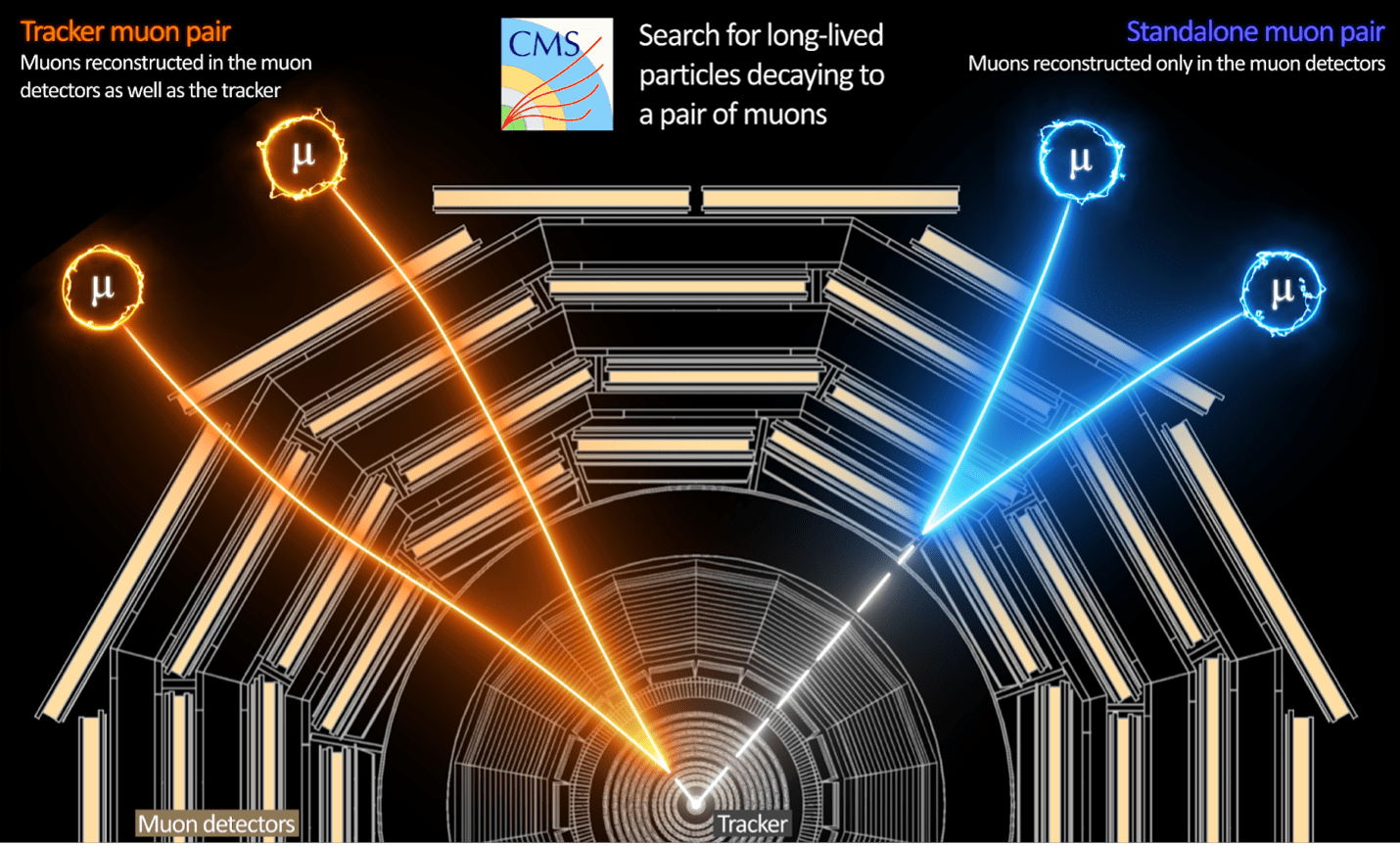

In the search for dark matter particles, there are two main approaches. The first is to look for particles that happen to decay naturally as they pass by. This typically involves neutrino observatories such as IceCube where a dark matter particle particle colliding with a nuclei might trigger a faint burst of light. So far this has turned up nothing. The second approach is to slam particles together in a particle accelerator. This approach has also failed to find dark matter particles, but there have been enough interesting hints that CERN is having a go. Their latest run is looking for what are known as dark photons.

Continue reading “CERN Has Joined the Search for Dark Photons”CERN Declares War On The Standard Model

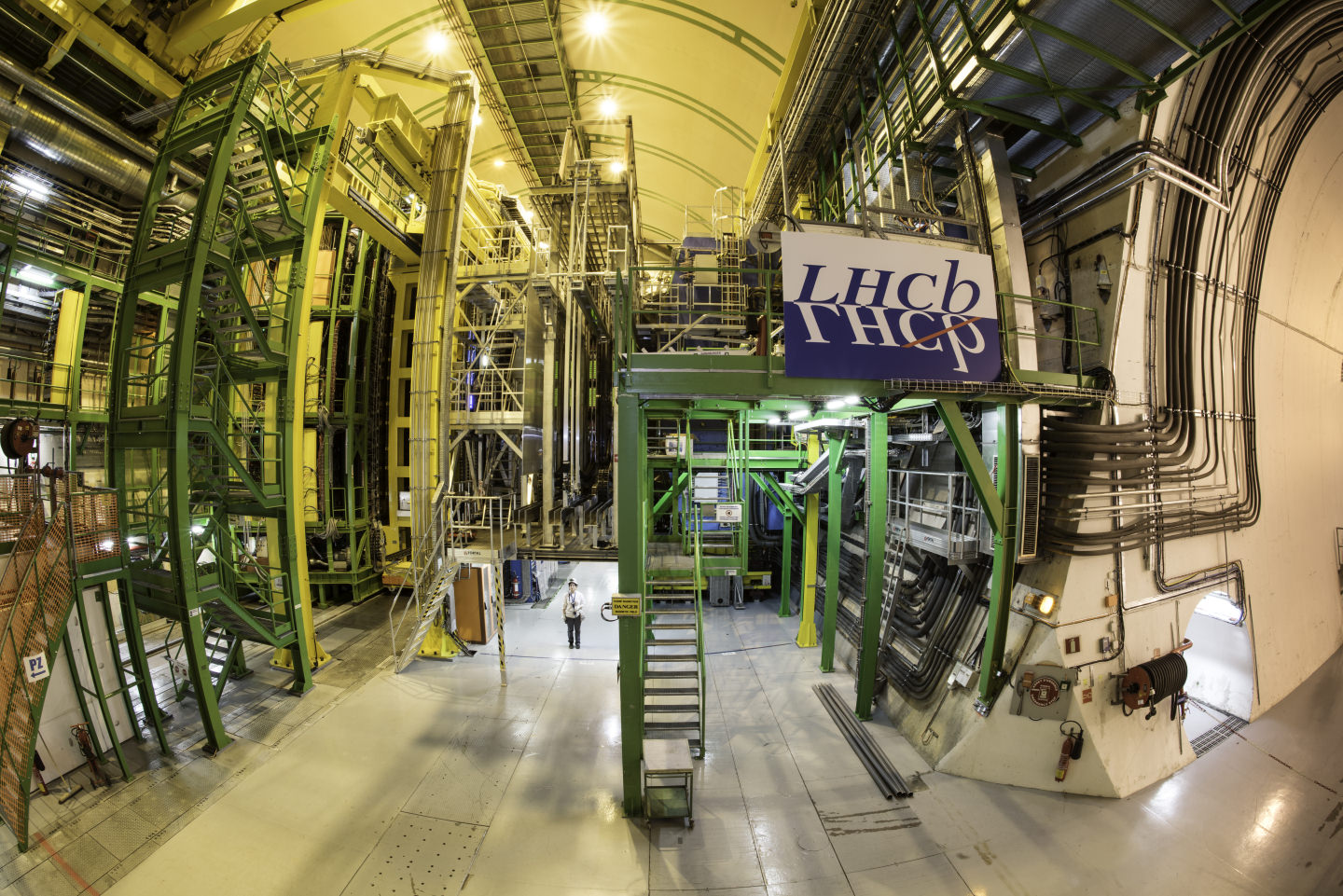

Ever since the discovery of the Higgs Boson in 2012, the Large Hadron Collider has been dedicated to searching for the existence of physics that go beyond the Standard Model. To this end, the Large Hadron Collider beauty experiment (LHCb) was established in 1995, specifically for the purpose of exploring what happened after the Big Bang that allowed matter to survive and create the Universe as we know it.

Since that time, the LHCb has been doing some rather amazing things. This includes discovering five new particles, uncovering evidence of a new manifestation of matter-antimatter asymmetry, and (most recently) discovering unusual results when monitoring beta decay. These findings, which CERN announced in a recent press release, could be an indication of new physics that are not part of the Standard Model.

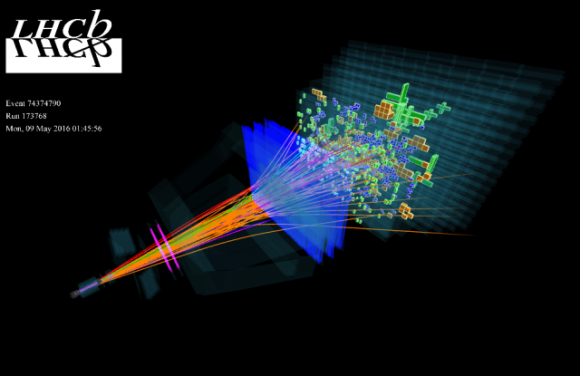

In this latest study, the LHCb collaboration team noted how the decay of B0 mesons resulted in the production of an excited kaon and a pair of electrons or muons. Muons, for the record, are subatomic particles that are 200 times more massive than electrons, but whose interactions are believed to be the same as those of electrons (as far as the Standard Model is concerned).

This is what is known as “lepton universality”, which not only predicts that electrons and muons behave the same, but should be produced with the same probability – with some constraints arising from their differences in mass. However, in testing the decay of B0 mesons, the team found that the decay process produced muons with less frequency. These results were collected during Run 1 of the LHC, which ran from 2009 to 2013.

The results of these decay tests were presented on Tuesday, April 18th, at a CERN seminar, where members of the LHCb collaboration team shared their latest findings. As they indicated during the course of the seminar, these findings are significant in that they appear to confirm results obtained by the LHCb team during previous decay studies.

This is certainly exciting news, as it hints at the possibility that new physics are being observed. With the confirmation of the Standard Model (made possible with the discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012), investigating theories that go beyond this (i.e. Supersymmetry) has been a major goal of the LHC. And with its upgrades completed in 2015, it has been one of the chief aims of Run 2 (which will last until 2018).

Naturally, the LHCb team indicated that further studies will be needed before any conclusions can be drawn. For one, the discrepancy they noted between the creation of muons and electrons carries a low probability value (aka. p-value) of between 2.2. to 2.5 sigma. To put that in perspective, the first detection of the Higgs Boson occurred at a level of 5 sigma.

In addition, these results are inconsistent with previous measurements which indicated that there is indeed symmetry between electrons and muons. As a result, more decay tests will have to be conducted and more data collected before the LHCb collaboration team can say definitively whether this was a sign of new particles, or merely a statistical fluctuation in their data.

The results of this study will be soon released in a LHCb research paper. And for more information, check out the PDF version of the seminar.

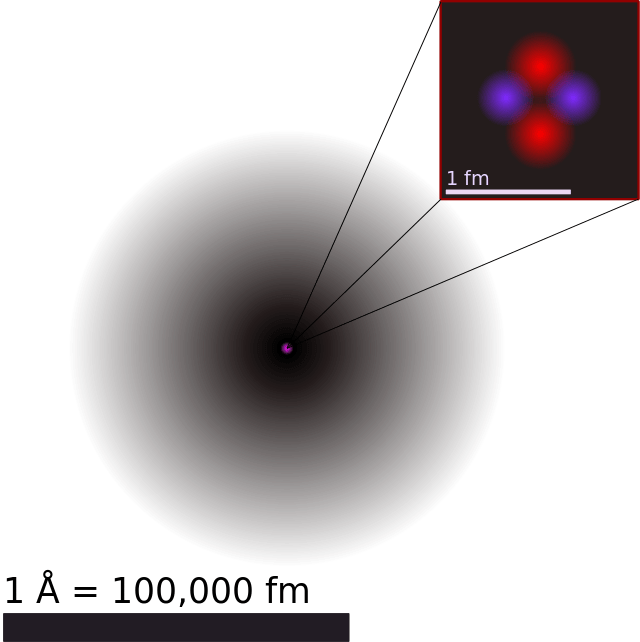

What Are The Parts Of An Atom?

Since the beginning of time, human beings have sought to understand what the universe and everything within it is made up of. And while ancient magi and philosophers conceived of a world composed of four or five elements – earth, air, water, fire (and metal, or consciousness) – by classical antiquity, philosophers began to theorize that all matter was actually made up of tiny, invisible, and indivisible atoms.

Since that time, scientists have engaged in a process of ongoing discovery with the atom, hoping to discover its true nature and makeup. By the 20th century, our understanding became refined to the point that we were able to construct an accurate model of it. And within the past decade, our understanding has advanced even further, to the point that we have come to confirm the existence of almost all of its theorized parts.