[/caption]

Is this 2-meter-high slab of lichen-covered rock in a UK park an astronomical marker used by Neolithic people? Researchers from Nottingham Trent University are suggesting that may in fact be the case, based on the stone’s alignment, angle and proximity to other significant Stone and Bronze Age sites nearby.

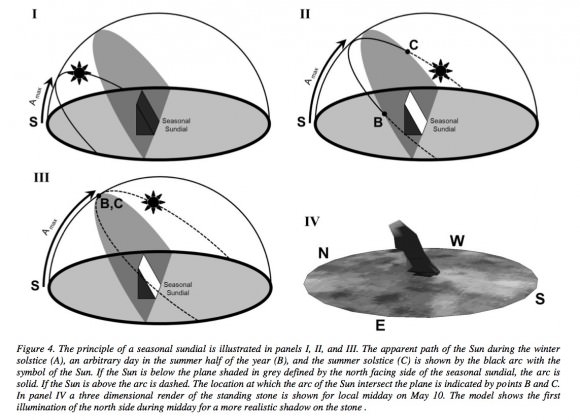

The angular rock, known as the Gardom’s Edge Monolith, resides within the Peak District National Park in the central northern area of England. The research team has found that it’s aligned in such a way that its north side slopes at an angle equal to the maximum altitude of the Sun during the summer solstice.

Not thought to be so much a sundial as a seasonal dial, the shadows cast by the monolith seem to mark specific times of year… possibly denoting the “life cycle” of the Sun in the heavens.

Standing stones being rare in the region, It’s estimated that the monolith was set in place anywhere from 2,500 — 1,500 B.C. Evidence of packed stones and earth at the base also suggests human placement.

The team believes that the stone may have been a gathering point for ancient communities in the area.

“The stone would have been an ideal marker for a social arena for seasonal gatherings,” said Dr. Daniel Brown, lead author of the team’s paper. “It’s not a sundial in the sense that people would have used it to determine an exact time. We think that it was set in position to give a symbolic meaning to its location, a bit like the way that some religious buildings are aligned in a specific direction for symbolic reasons.”

Computer modeling of the stone and the Sun’s position throughout the year show that the stone’s slanted side would be in shadow during the winter, while during the summer it would be lit in the morning and afternoon. During midsummer, however, it would be illuminated all day.

More modeling and photographic work will be needed to confirm this hypothesis. If supported, it could lead to more archaeological study of the area.

Read the team’s full paper here, and read more on Sci-News.com.