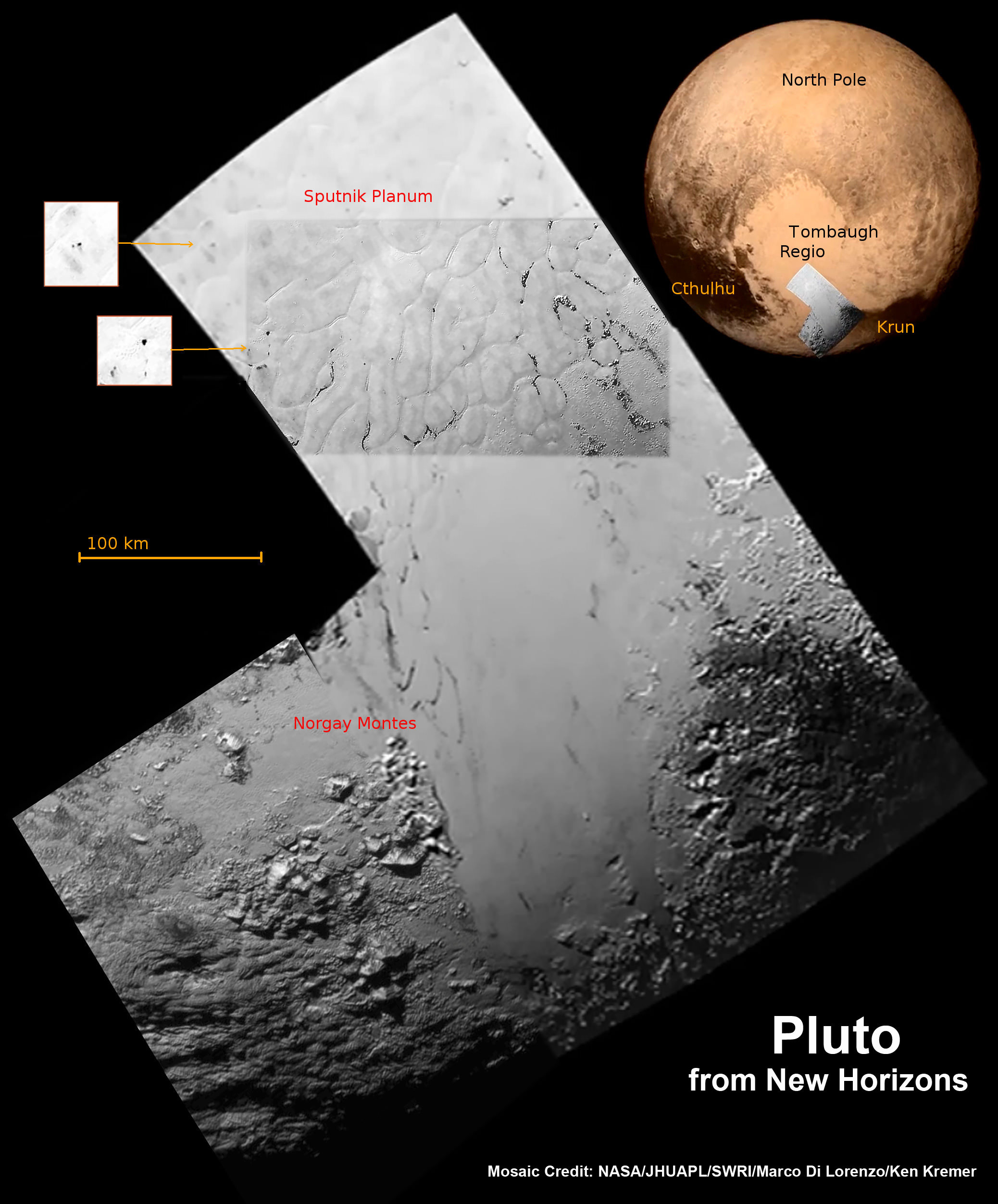

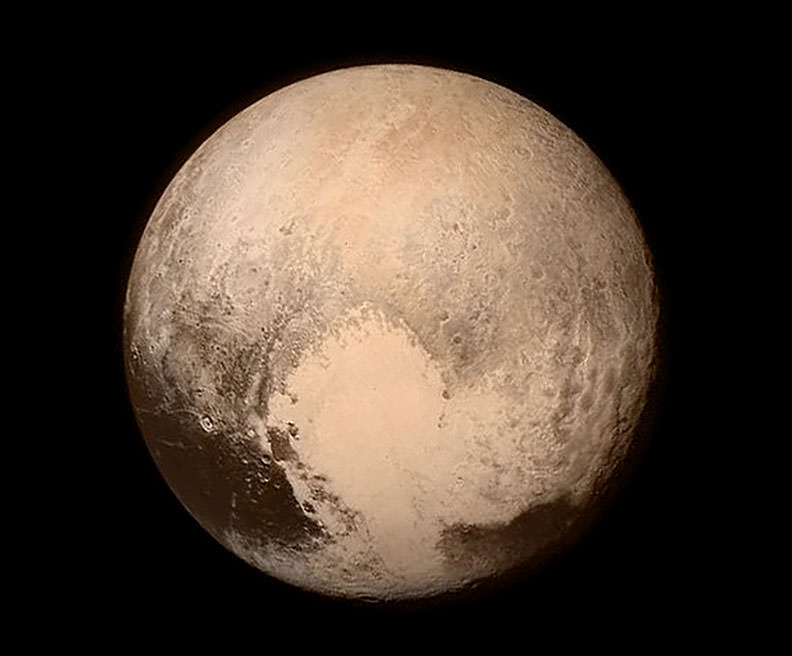

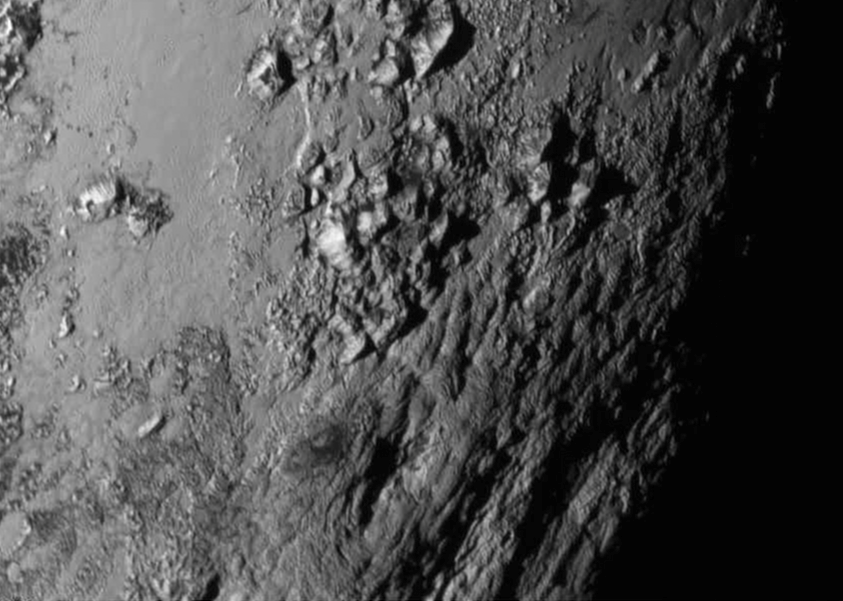

APPLIED PHYSICS LABORATORY, LAUREL, MD – The highest resolution images ever taken of Pluto by humanity’s first spacecraft ever to visit the last planet in our solar system revealed unanticipated new discoveries of ice mountains as tall as the Rockies and vast craterless plains spanning hundreds of miles (kilometers) across – are now shown in our newly created context mosaic (featured above and below) of the heart-shaped ‘Tombaugh Regio’ area that dominates the alien planet’s surface.

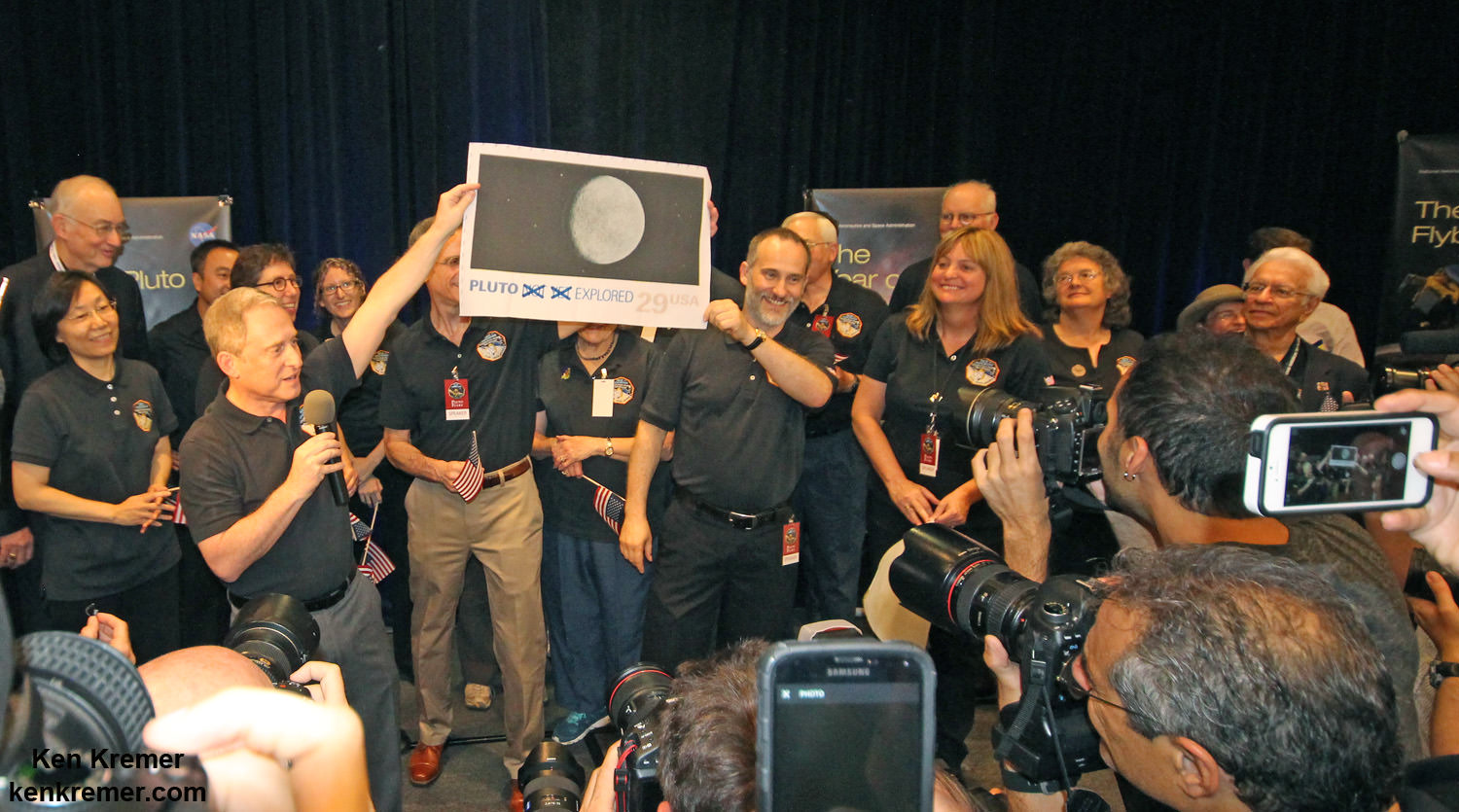

These stunning and astoundingly young features only now unveiled on Pluto’s surface were created in very recent times, geologically speaking said top scientists leading NASA’s resounding successful New Horizons mission, at a media briefing on July 17.

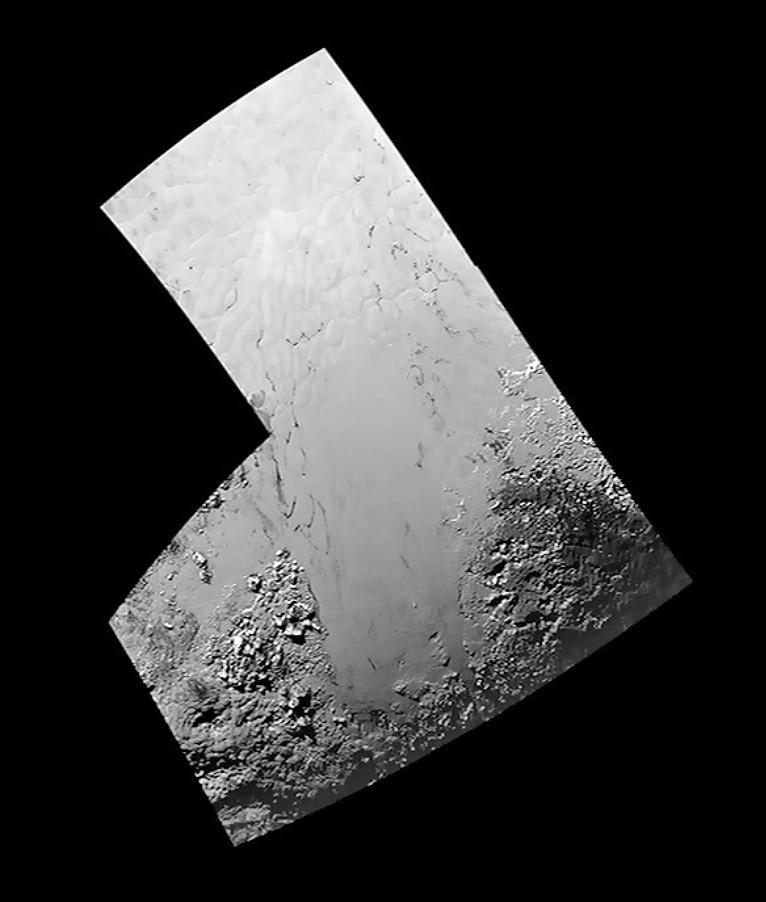

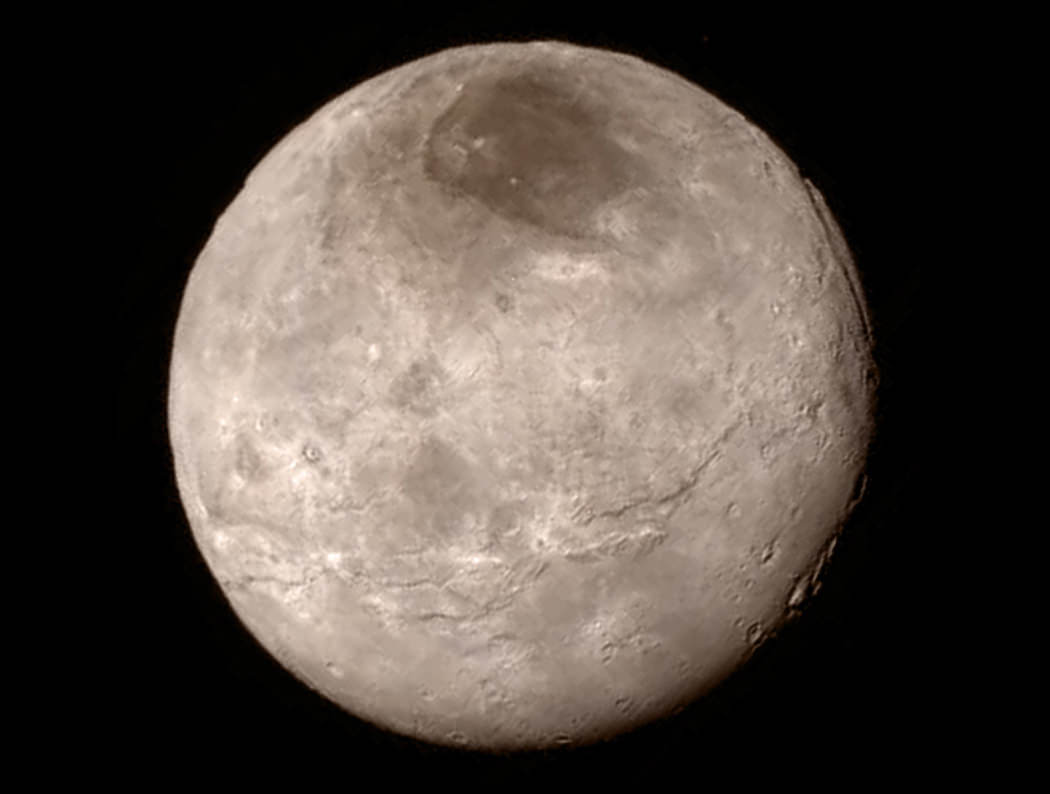

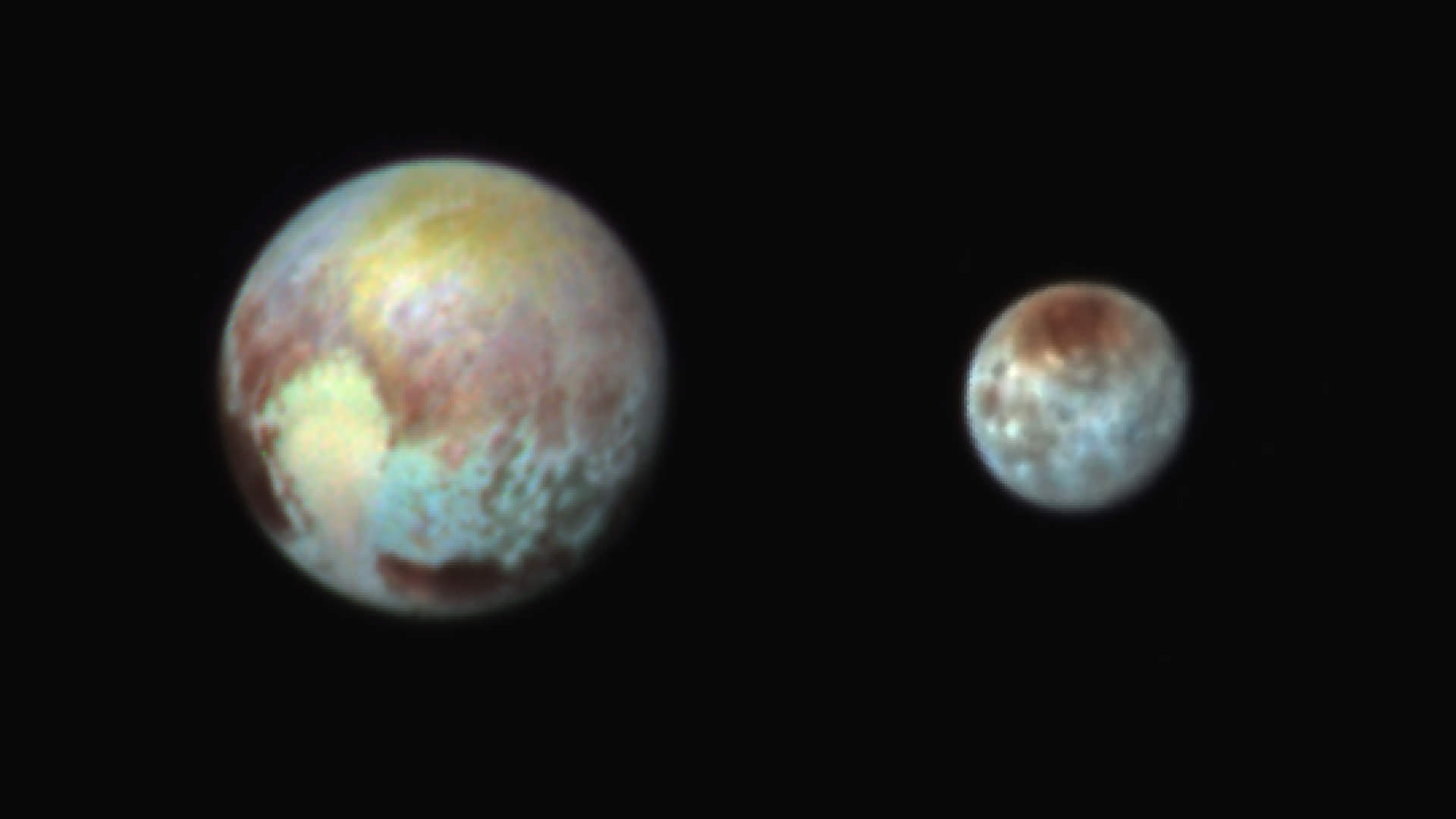

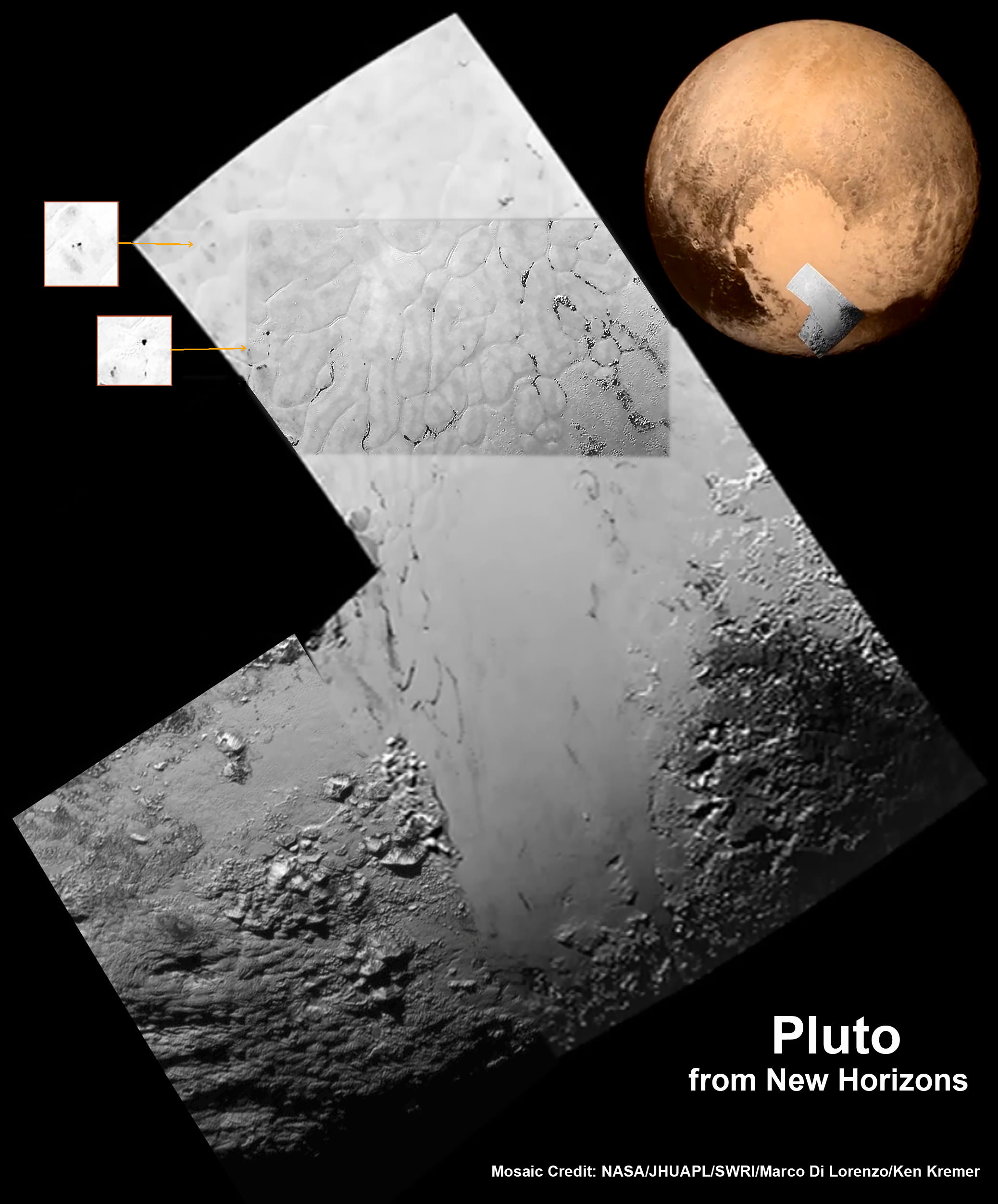

This first high resolution surface mosaic was created from a newly unveiled series of black and white images centered in the Heart of Pluto’s huge ‘Heart, including the ice mountains of ‘Sputnik Planum’ and icy plains of ‘Norgay Montes.’

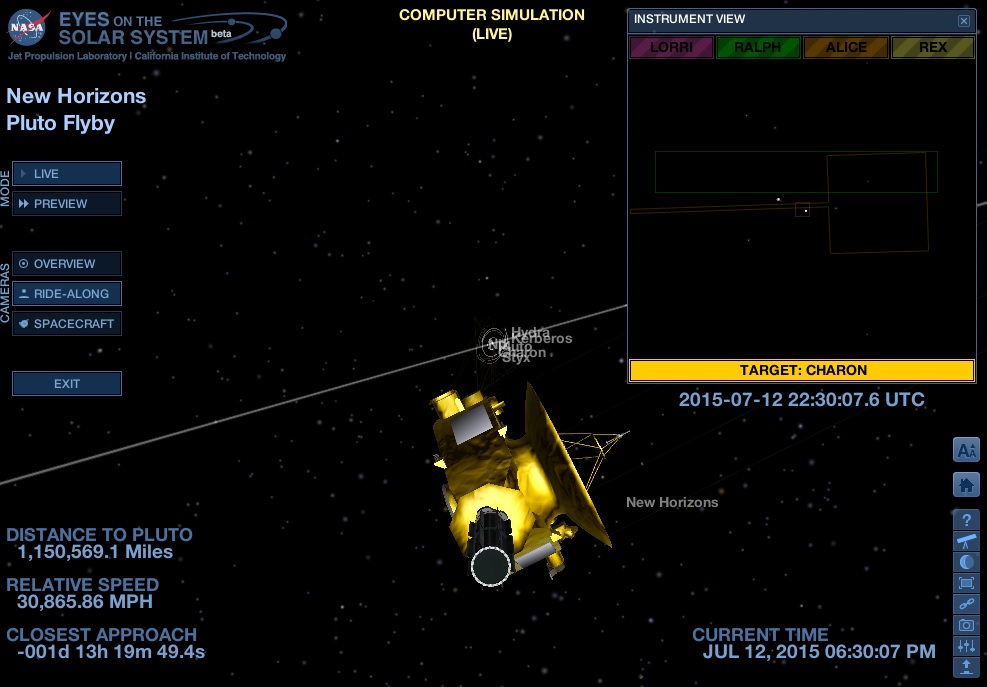

They were captured by New Horizons’ high resolution Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) on July 14 as the probe barreled past the Pluto-Charon binary planet system only four days ago on Tuesday, July 14, at over 31,000 mph (49,600 kph).

These highest resolution LORRI images focused on the “Heart of the Heart” of Pluto have now been stitched into a mosaic by the image processing team of Marco Di Lorenzo and Ken Kremer.

Pluto’s bright heart-shaped region has now been informally renamed “Tombaugh Regio,’ announced John Spencer, New Horizons science team co-investigator at the post flyby media briefing on July 15.

The mosaic of Pluto’s ‘Tombaugh Regio’ is based on the initial imagery released so far as of July 17.

A pair of high resolution LORRI images was aimed at areas now informally named Norgay Montes (Norgay Mountains) and Sputnik Planum (Sputnik Plain).

Norgay Montes is informally named for Tenzing Norgay, one of the first two humans to reach the summit of Mount Everest, along with Sir Edmund Hillary. Sputnik Planum is informally named for Earth’s first artificial satellite launched by the Soviet Union in 1957.

The two LORRI images are draped over a wider, lower resolution view of Tombaugh Regio – in annotated and unannotated versions. This is highest resolution currently available.

To the left of the mosaic are two small inserts showing possible “wind streaks” say the researchers.

To the right of the mosaic is a global view of Pluto showing the location of Tombaugh Regio and also outlined to show the precise location of the high resolution LORRI mosaic.

The LORRI images were taken from a distance of 48,000 miles (77,000 kilometers) from the surface of the planet about 1.5 hours prior to the closest approach at 7:49 a.m. EDT on July 14. The images easily resolve structures smaller than a mile across.

The frozen region of Norgay Montes is situated north of Pluto’s icy mountain range at Sputnik Planum.

“This terrain is not easy to explain,” said Jeff Moore, leader of the New Horizons Geology, Geophysics and Imaging Team (GGI) at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California.

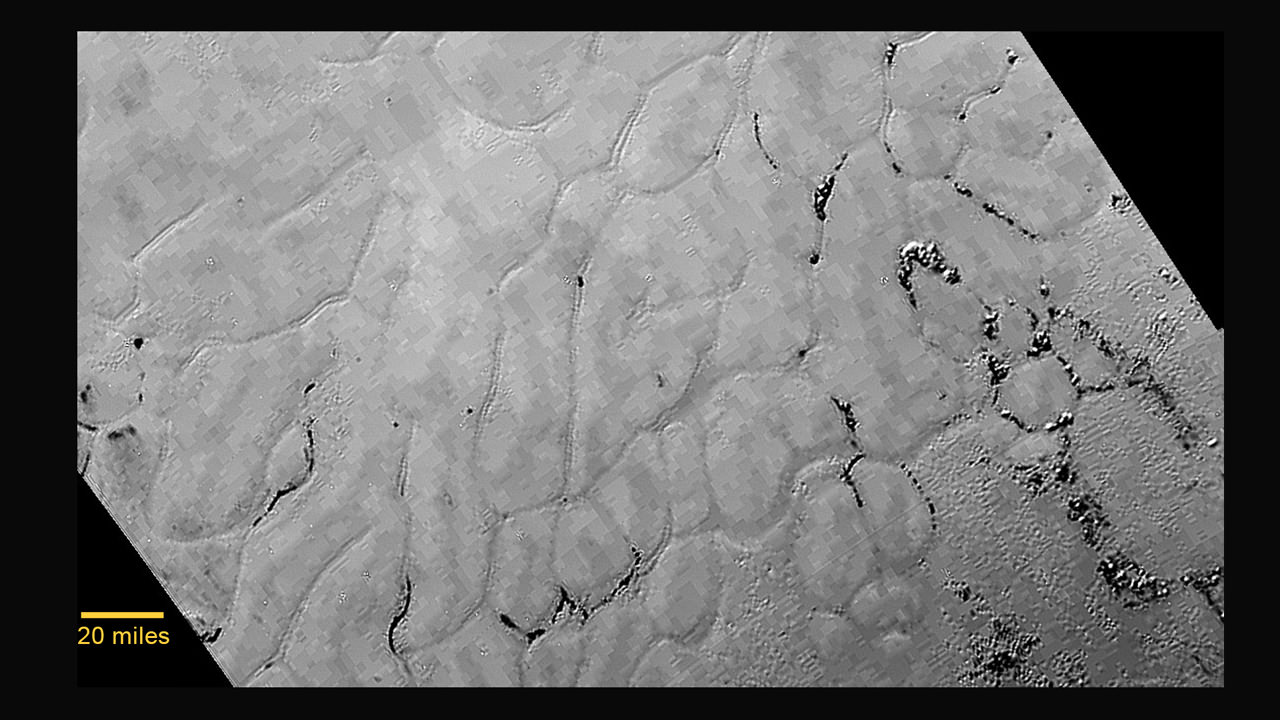

“The discovery of vast, craterless, very young plains on Pluto exceeds all pre-flyby expectations.”

“The landscape is astoundingly amazing. There are a few ancient impact craters on Pluto. But other areas like “Tombaugh Regio” show no craters. The landform change processes are occurring into current geologic times.”

“There are no impact craters in a frozen area north of Pluto’s icy mountains we are now informally calling ‘Sputnik Planum’ after Earth’s first artificial satellite.”

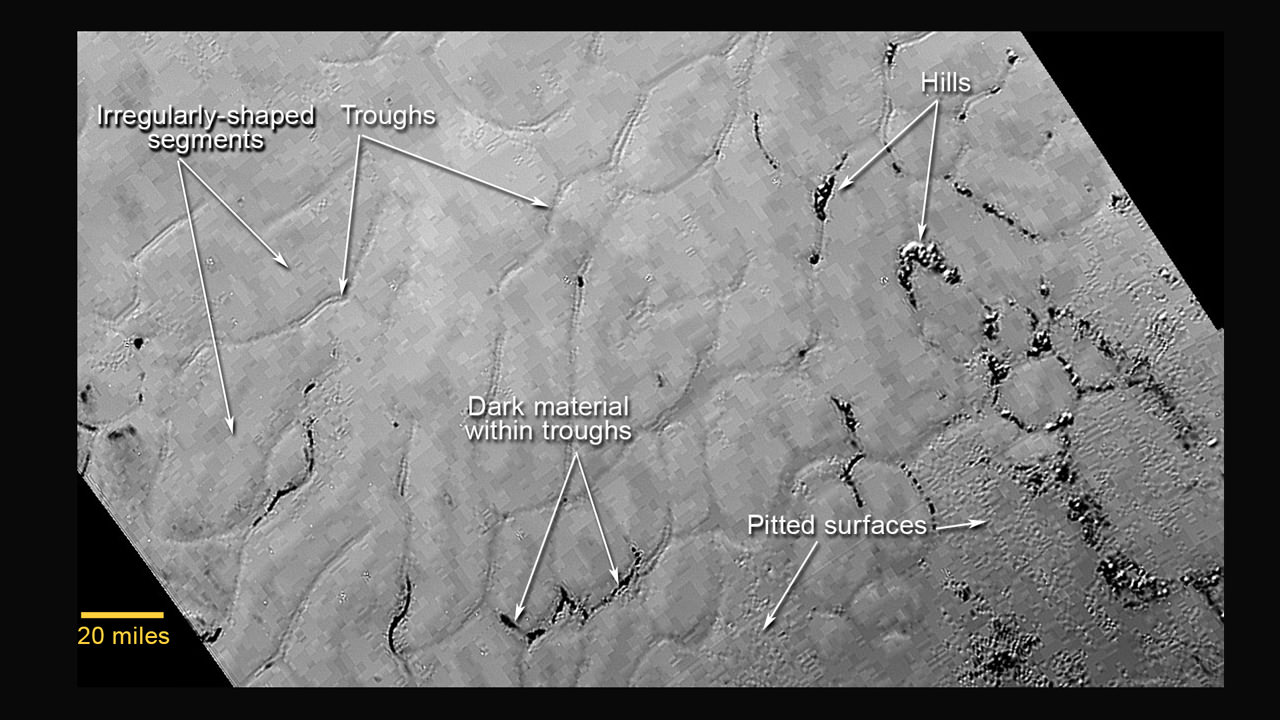

‘Sputnik Planum’ is composed of a broken surface of irregularly-shaped segments. The polygonal shaped areas are roughly 12 miles (20 kilometers) across, bordered by what appear to be shallow troughs based on a quick look at the data.

The mountain ranges height rival those of the Rockies, says Moore.

The new LORRI close-ups show the icy mountain range has peaks jutting as high as 11,000 feet (3,500 meters) above the surface, announced John Spencer, New Horizons science team co-investigator at the media briefing.

“It’s a very young surface, probably formed less than 100 million years old,’ said Spencer. “It may be active now.”

“Judging from the absence of impact craters, it’s clear that Sputnik Planum couldn’t possibly be more than 100 million years old, and possibly is still being shaped to this day by geologic processes,” noted Moore. “This could be only a week old for all we know.”

During the fast flyby encounter, the New Horizons spacecraft pointed its suite of seven science instruments exclusively on all the bodies in the Pluto system, to maximize the capture of scientific data, as quickly as possible, and store it onto its two solid state digital recorders for later playback.

A major challenge for the mission is the rather slow “downlink” transmission of data back to Mission Control on Earth. Since the average “downlink” is only about 2 kilobits per second via its two transmitters, it will take about 16 months to send all the flyby data back to Earth.

Therefore the team has carefully selected just a few of the highest resolution images and other key instrument data for quick playback. The remaining flyby data will be prioritized for streaming.

“Over 50 gigabits of data were collected during the encounter and flyby periods,” New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, Colorado, said during the July 17 media briefing.

“So far less than 1 gigabit of data has been returned.”

New Horizons discovered that Pluto is the biggest object in the outer solar system and thus the ‘King of the Kuiper Belt’.

The Kuiper Belt comprises the third and outermost region of worlds in our solar system.

If the spacecraft remains healthy as expected, the science team plans to target New Horizons to fly by another smaller Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) as soon as 2018.

Watch for Ken’s continuing coverage of the Pluto flyby. He was onsite reporting live on the flyby and media briefings for Universe Today from the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), in Laurel, Md.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and planetary science and human spaceflight news.