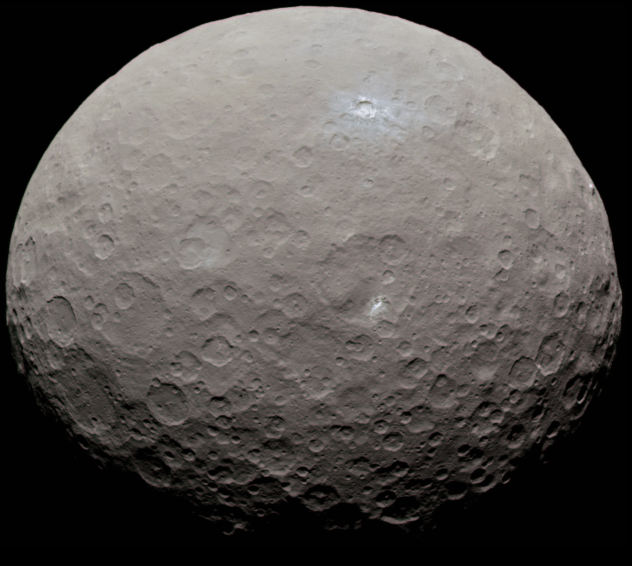

In March of 2015, NASA’s Dawn mission became the first spacecraft to visit the protoplanet Ceres, the largest body in the Main Asteroid Belt. It was also the first spacecraft to visit a dwarf planet, having arrived a few months before the New Horizons mission made its historic flyby of Pluto. Since that time, Dawn has revealed much about Ceres, which in turn is helping scientists to understand the early history of the Solar System.

Last year, scientists with NASA’s Dawn mission made a startling discovery when they detected complex chains of carbon molecules – organic material essential for life – in patches on the surface of Ceres. And now, thanks to a new study conducted by a team of researchers from Brown University (with the support of NASA), it appears that these patches contain more organic material than previously thought.

The new findings were recently published in the scientific journal Geophysical Research Letters under the title “New Constraints on the Abundance and Composition of Organic Matter on Ceres“. The study was led by Hannah Kaplan, a postdoctoral researcher at Brown University, with the assistance of Ralph E. Milliken and Conel M. O’D. Alexander – an assistant professor at Brown University and a researcher from the Carnegie Institution of Washington, respectively.

The organic materials in question are known as “aliphatics”, a type of compound where carbon atoms form open chains that are commonly bound with oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur and chlorine. To be fair, the presence of organic material on Ceres does not mean that the body supports life since such molecules can arise from non-biological processes.

Aliphatics have also been detected on other planets in the form of methane (on Mars and especially on Saturn’s largest moon, Titan). Nevertheless, such molecules remains an essential building block for life and their presence at Ceres raises the question of how they got there. As such, scientists are interested in how it and other life-essential elements (like water) has been distributed throughout the Solar System.

Since Ceres is abundant in both organic molecules and water, it raises some intriguing possibilities about the protoplanet. The results of this study and the methods they used could also provide a template for interpreting data for future missions. As Dr. Kaplan – who led the research while completing her PhD at Brown – explained in a recent Brown University press release:

“What this paper shows is that you can get really different results depending upon the type of organic material you use to compare with and interpret the Ceres data. That’s important not only for Ceres, but also for missions that will soon explore asteroids that may also contain organic material.”

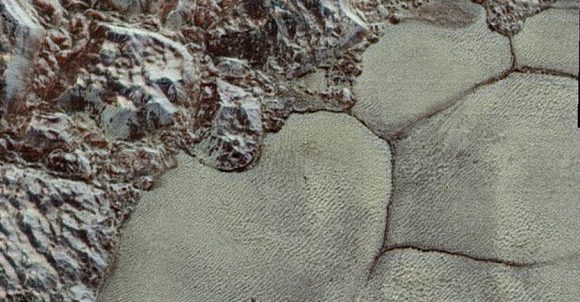

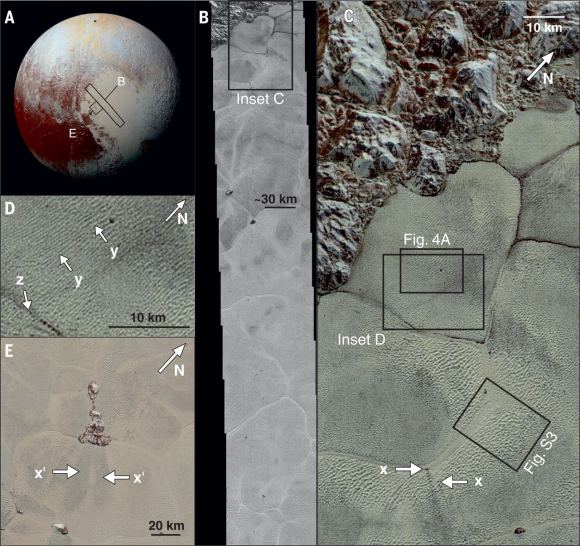

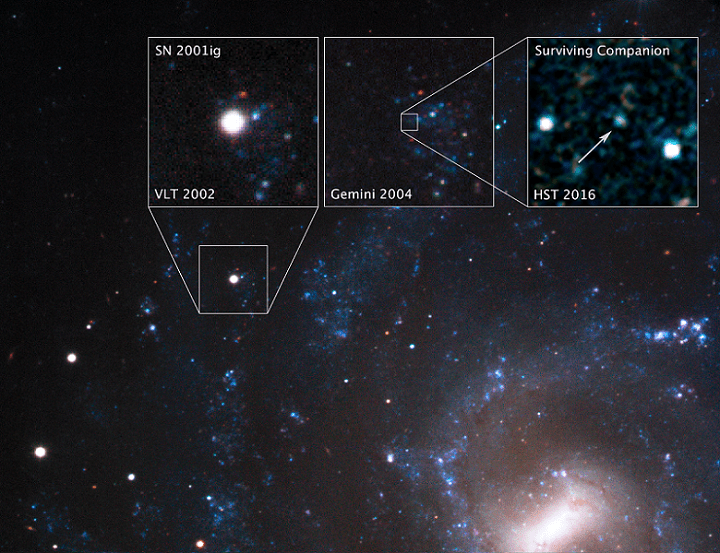

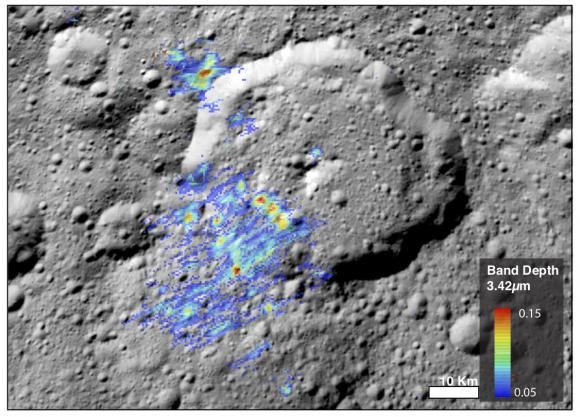

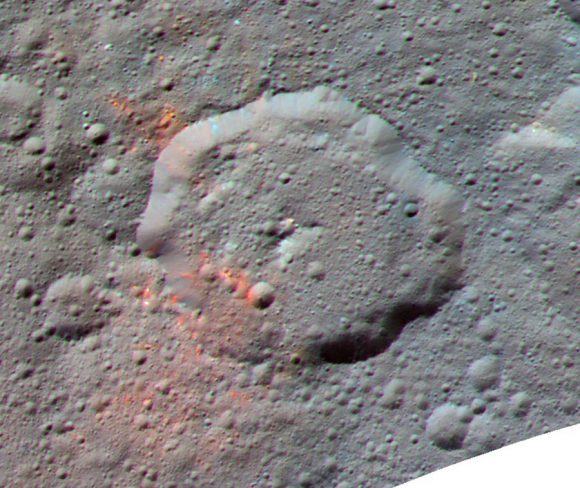

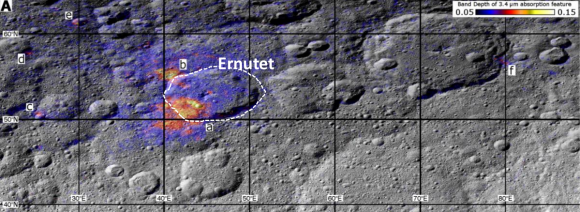

The original discovery of organics on Ceres took place in 2017 when an international team of scientists analyzed data from the Dawn mission’s Visible and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIRMS). The data provided by this instrument indicated the presence of these hydrocarbons in a 1000 km² region around of the Ernutet crater, which is located in the northern hemisphere of Ceres and measures about 52 km (32 mi) in diameter.

To get an idea of how abundant the organic compounds were, the original research team compared the VIRMS data to spectra obtained in a laboratory from Earth rocks with traces of organic material. From this, they concluded that between 6 and 10% of the spectral signature detected on Ceres could be explained by organic matter.

They also hypothesized that the molecules were endogenous in origin, meaning that they originated from inside the protoplanet. This was consistent with previous surveys that showed signs of hydorthermal activity on Ceres, as well others that have detected ammonia-bearing hydrated minerals, water ice, carbonates, and salts – all of which suggested that Ceres had an interior environment that can support prebiotic chemistry.

But for the sake of their study, Kaplan and her colleagues re-examined the data using a different standard. Instead of relying on Earth rocks for comparison, they decided to examine an extraterrestrial source. In the past, some meteorites – such as carbonaceous chondrites – have been shown to contain organic material that is slightly different than what we are familiar with here on Earth.

After re-examining the spectral data using this standard, Kaplan and her team determined that the organics found on Ceres were distinct from their terrestrial counterparts. As Kaplan explained:

“What we find is that if we model the Ceres data using extraterrestrial organics, which may be a more appropriate analog than those found on Earth, then we need a lot more organic matter on Ceres to explain the strength of the spectral absorption that we see there. We estimate that as much as 40 to 50 percent of the spectral signal we see on Ceres is explained by organics. That’s a huge difference compared to the six to 10 percent previously reported based on terrestrial organic compounds.”

If the concentrations of organic material are indeed that high, then it raises new questions about where it came from. Whereas the original discovery team claimed it was endogenous in origin, this new study suggests that it was likely delivered by an organic-rich comet or asteroid. On the one hand, the high concentrations on the surface of Ceres are more consistent with a comet impact.

This is due to the fact that comets are known to have significantly higher internal abundances of organics compared with primitive asteroids, similar to the 40% to 50% figure this study suggests for these locations on Ceres. However, much of those organics would have been destroyed due to the heat of the impact, which leaves the question of how they got there something of a mystery.

If they did arise endogenously, then there is the question of how such high concentrations emerged in the northern hemisphere. As Ralph Milliken explained:

“If the organics are made on Ceres, then you likely still need a mechanism to concentrate it in these specific locations or at least to preserve it in these spots. It’s not clear what that mechanism might be. Ceres is clearly a fascinating object, and understanding the story and origin of organics in these spots and elsewhere on Ceres will likely require future missions that can analyze or return samples.”

Given that the Main Asteroid Belt is composed of material left over from the formation of the Solar System, determining where these organics came from is expected to shed light on how organic molecules were distributed throughout the Solar System early in its history. In the meantime, the researchers hope that this study will inform upcoming sample missions to near-Earth asteroids (NEAs), which are also thought to host water-bearing minerals and organic compounds.

These include the Japanese spacecraft Hayabusa2, which is expected to arrive at the asteroid Ryugu in several weeks’ time, and NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission – which is due to reach the asteroid Bennu in August. Dr. Kaplan is currently a science team member with the OSIRIS-REx mission and hopes that the Dawn study she led will help the OSIRIS-REx‘s mission characterize Bennu’s environment.

“I think the work that went into this study, which included new laboratory measurements of important components of primitive meteorites, can provide a framework of how to better interpret data of asteroids and make links between spacecraft observations and samples in our meteorite collection,” she said. “As a new member to the OSIRIS-REx team, I’m particularly interested in how this might apply to our mission.”

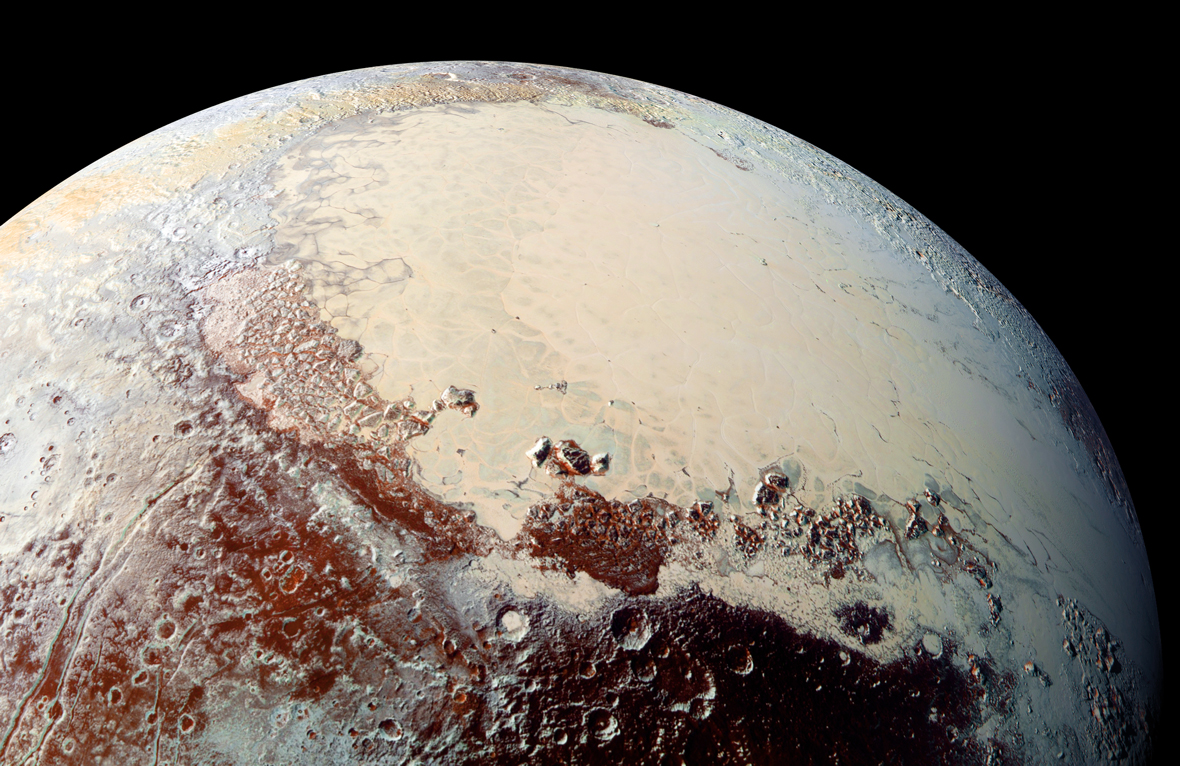

The New Horizons mission is also expected to rendezvous with the Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) 2014 MU69 on January 1st, 2019. Between these and other studies of “ancient objects” in our Solar System – not to mention interstellar asteroids that are being detected for the first time – the history of the Solar System (and the emergence of life itself) is slowly becoming more clear.

Further Reading: Brown University, Geophysical Research Letters