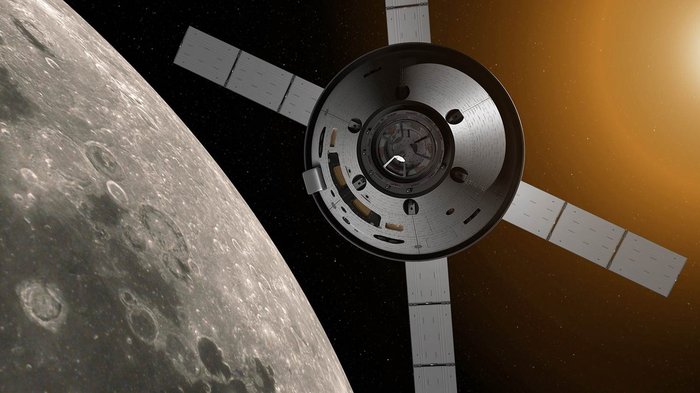

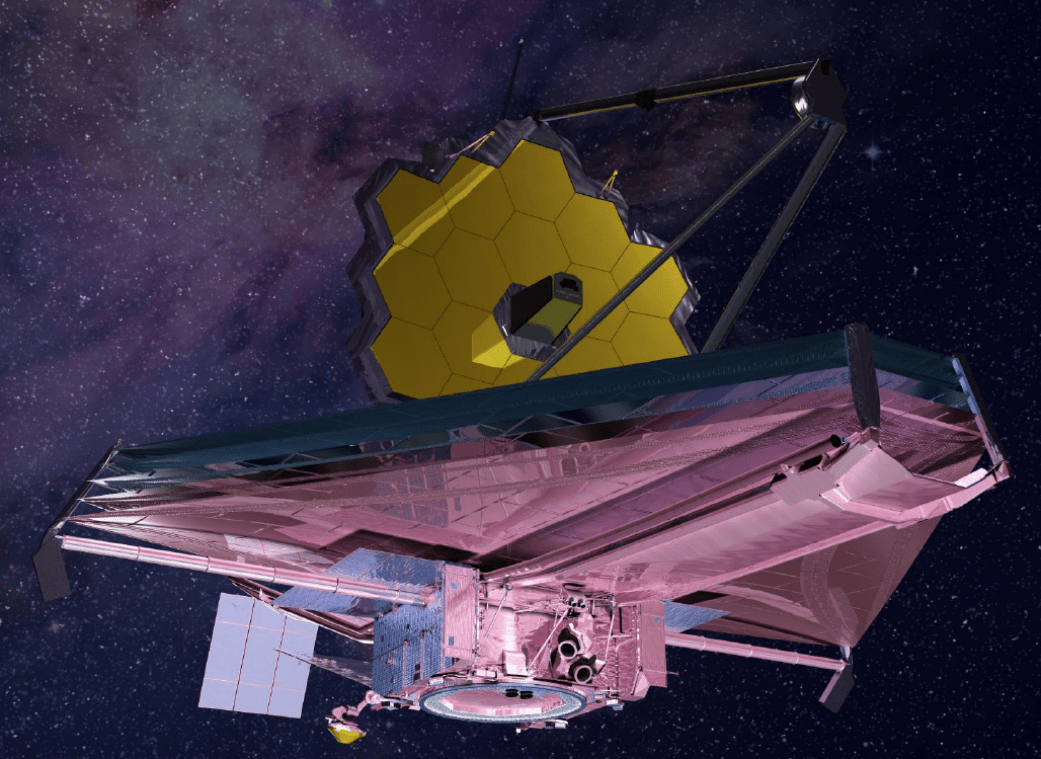

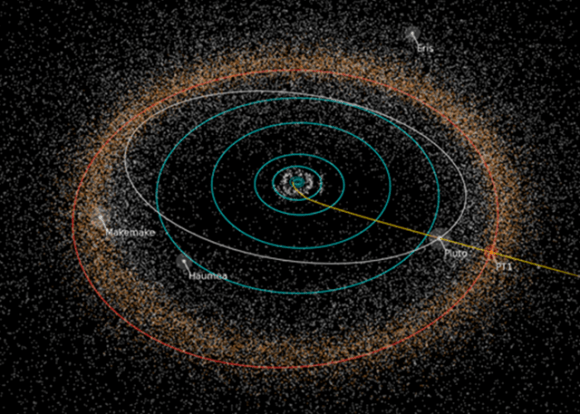

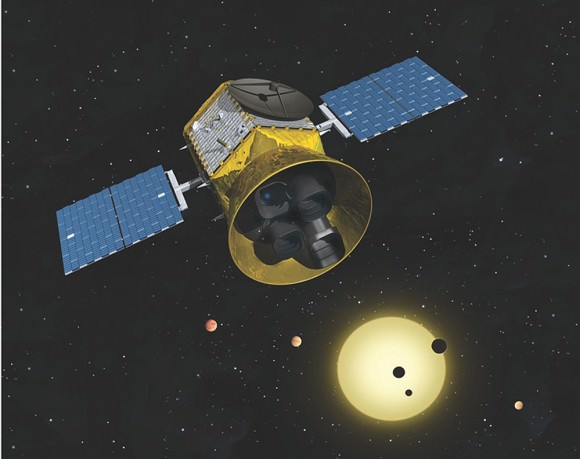

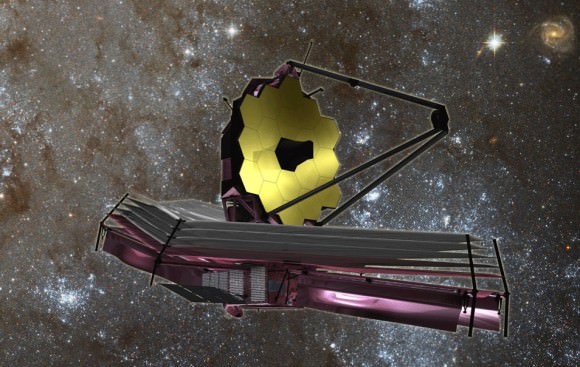

With the recent launch of the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) – which took place on Wednesday, April 18th, 2018 – a lot of attention has been focused on the next-generation space telescopes that will be taking to space in the coming years. These include not only the James Webb Space Telescope, which is currently scheduled for launch in 2020, but some other advanced spacecraft that will be deployed by the 2030s.

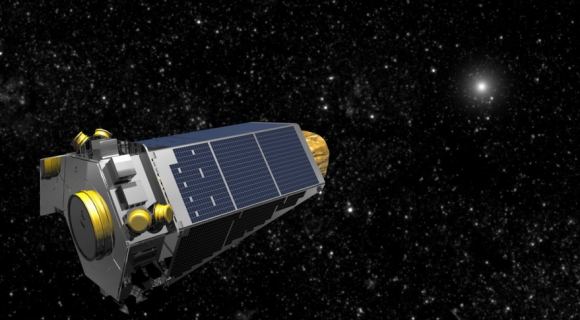

Such was the subject of the recent 2020 Decadal Survey for Astrophysics, which included four flagship mission concepts that are currently being studied. When these missions take to space, they will pick up where missions like Hubble, Kepler, Spitzer and Chandra left off, but will have greater sensitivity and capability. As such, they are expected to reveal a great deal more about our Universe and the secrets it holds.

As expected, the mission concepts submitted to the 2020 Decadal Survey cover a wide range of scientific goals – from observing distant black holes and the early Universe to investigating exoplanets around nearby stars and studying the bodies of the Solar System. These ideas were thoroughly vetted by the scientific community, and four have been selected as being worthy of pursuit.

As Susan Neff, the chief scientist of NASA’s Cosmic Origins Program, explained in a recent NASA press release:

“This is game time for astrophysics. We want to build all these concepts, but we don’t have the budget to do all four at the same time. The point of these decadal studies is to give members of the astrophysics community the best possible information as they decide which science to do first.”

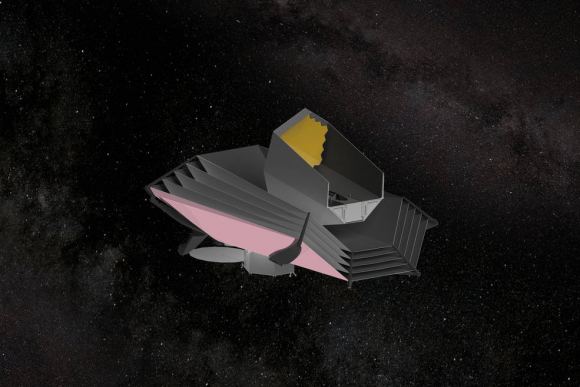

The four selected concepts include the Large Ultraviolet/Optical/Infrared Surveyor (LUVOIR), a giant space observatory developed in the tradition of the Hubble Space Telescope. As one of two concepts being investigated by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, this mission concept calls for a space telescope with a massive segmented primary mirror that measures about 15 meters (49 feet) in diameter.

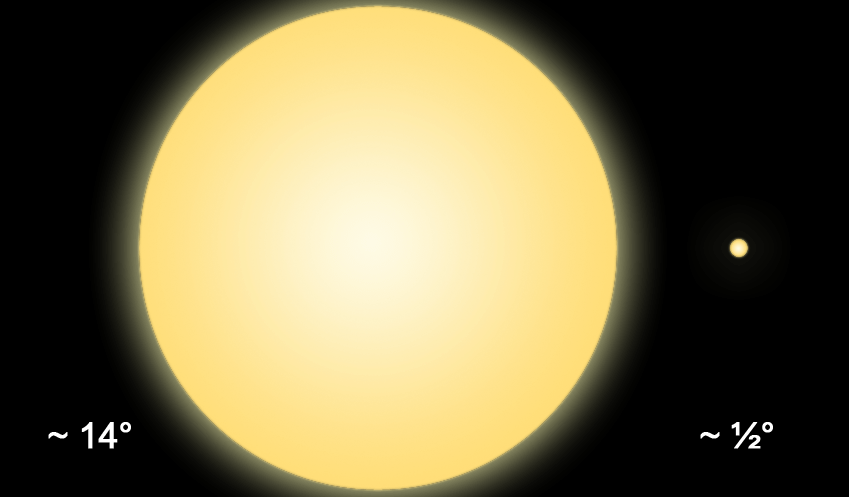

In comparison, the JWST‘s (currently the most advanced space telescope) primary mirror measures 6.5 m (21 ft 4 in) in diameter. Much like the JWST, LUVOIR’s mirror would be made up of adjustable segments that would unfold once it deployed to space. Actuators and motors would actively adjust and align these segments in order to achieve the perfect focus and capture light from faint and distant objects.

With these advanced tools, LUVOIR would be able to directly image Earth-sized planets and assess their atmospheres. As Study Scientist Aki Roberge explained:

“This mission is ambitious, but finding out if there is life outside the solar system is the prize. All the technology tall poles are driven by this goal… Physical stability, plus active control on the primary mirror and an internal coronagraph (a device for blocking starlight) will result in picometer accuracy. It’s all about control.”

There’ also the Origins Space Telescope (OST), another concept being pursued by the Goddard Space Flight Center. Much like the Spitzer Space Telescope and the Herschel Space Observatory, this far-infrared observatory would offer 10,000 times more sensitivity than any preceding far-infrared telescope. Its goals include observing the farthest reaches of the universe, tracing the path of water through star and planet formation, and searching for signs of life in the atmospheres of exoplanets.

Its primary mirror, which would measure about 9 m (30 ft) in diameter, would be the first actively cooled telescope, keeping its mirror at a temperature of about 4 K (-269 °C; -452 °F) and its detectors at a temperature of 0.05 K. To achieve this, the OST team will rely on flying layers of sunshields, four cryocoolers, and a multi-stage continuous adiabatic demagnetization refrigerator (CADR).

According to Dave Leisawitz, a Goddard scientist and OST study scientist, the OST is especially reliant on large arrays of superconducting detectors that measure in the millions of pixels. “When people ask about technology gaps in developing the Origins Space Telescope, I tell them the top three challenges are detectors, detectors, detectors,” he said. “It’s all about the detectors.”

Specifically, the OST would rely on two emerging types of detectors: Transition Edge Sensors (TESs) or Kinetic Inductance Detectors (KIDs). While still relatively new, TES detectors are quickly maturing and are currently being used in the HAWC+ instrument aboard NASA’s Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA).

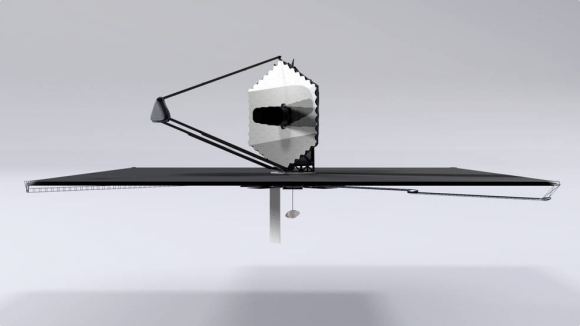

Then there’s the Habitable Exoplanet Imager (HabEx) which is being developed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Like LUVOIR, this telescope would also directly image planetary systems to analyze the composition of planets’ atmospheres with a large segmented mirror. In addition, it would study the earliest epochs in the history of the Universe and the life cycle of the most massive stars, thus shedding light on how the elements that are necessary for life are formed.

Also like LUVOIR, HabEx would be able to conduct studies in the ultraviolet, optical and near-infrared wavelengths, and be able to block out a parent star’s brightness so that it could see light being reflected off of any planets orbiting it. As Neil Zimmerman, a NASA expert in the field of coronagraphy, explained:

“To directly image a planet orbiting a nearby star, we must overcome a tremendous barrier in dynamic range: the overwhelming brightness of the star against the dim reflection of starlight off the planet, with only a tiny angle separating the two. There is no off-the-shelf solution to this problem because it is so unlike any other challenge in observational astronomy.”

To address this challenge, the HabEx team is considering two approaches, which include external petal-shaped star shades that block light and internal coronagraphs that prevent starlight from reaching the detectors. Another possibility being investigated is to apply carbon nanotubes onto the coronagraphic masks to modify the patterns of any diffracted light that still gets through.

Last, but not least, is the X-ray Surveyor known as Lynx being developed by the Marshall Space Flight Center. Of the four space telescopes, Lynx is the only concept which will examine the Universe in X-rays. Using an X-ray microcalorimeter imaging spectrometer, this space telescope will detect X-rays coming from Supermassive Black Holes (SMBHs) at the center of the earliest galaxies in the Universe.

This technique consists of X-ray photos hitting a detector’s absorders and converting their energy to heat, which is measured by a thermometer. In this way, Lynx will help astronomers unlock how the earliest SMBHs formed. As Rob Petre, a Lynx study member at Goddard, described the mission:

“Supermassive black holes have been observed to exist much earlier in the universe than our current theories predict. We don’t understand how such massive objects formed so soon after the time when the first stars could have formed. We need an X-ray telescope to see the very first supermassive black holes, in order to provide the input for theories about how they might have formed.”

Regardless of which mission NASA ultimately selects, the agency and individual centers have begun investing in advanced tools to pursue such concepts in the future. The four teams submitted their interim reports back in March. By next year, they are expected to finish final reports for the National Research Council (NRC), which will be used to inform its recommendations to NASA in the coming years.

As Thai Pham, the technology development manager for NASA’s Astrophysics Program Office, indicated:

“I’m not saying it will be easy. It won’t be. These are ambitious missions, with significant technical challenges, many of which overlap and apply to all. The good news is that the groundwork is being laid now.”

With TESS now deployed and the JWST scheduled to launch by 2020, the lessons learned in the next few years will certainly be incorporated into these missions. At present, it is not clear which of the following concepts will be going to space by the 2030s. However, between their advanced instruments and the lessons learned from past missions, we can expect that they will make some profound discoveries about the Universe.