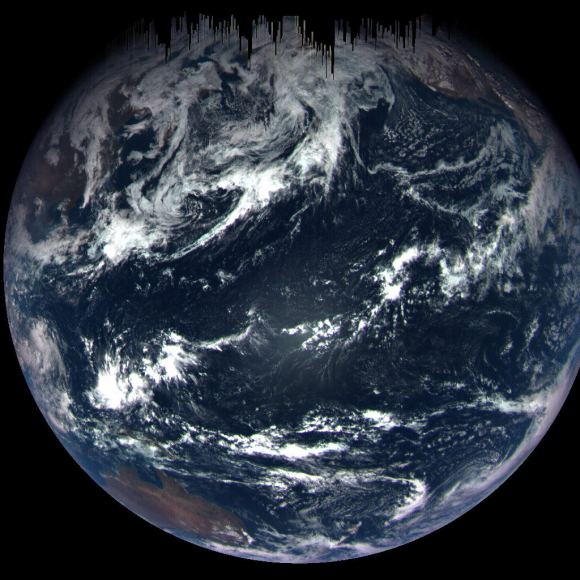

Some might say it’s paranoid to think about an asteroid hitting Earth and wiping us out. But the history of life on Earth shows at least 5 major extinctions. And at least one of them, about 65 million years ago, was caused by an asteroid.

Preparing for an asteroid strike, or rather preparing to prevent one, is rational thinking at its finest. Especially now that we can see all the Near Earth Asteroids (NEAs) out there. The chances of any single asteroid striking Earth may be small, but collectively, with over 15,000 NEAs catalogued by NASA, it may be only a matter of time until one comes for us. In fact, space rocks strike Earth every day, but they’re too small to cause any harm. It’s the ones large enough to do serious damage that concern NASA.

NASA has been thinking about the potential for an asteroid strike on Earth for a long time. They even have an office dedicated to it, called the Office of Planetary Defense, and minds there have been putting a lot of thought into detecting hazardous asteroids, and deflecting or destroying any that pose a threat to Earth.

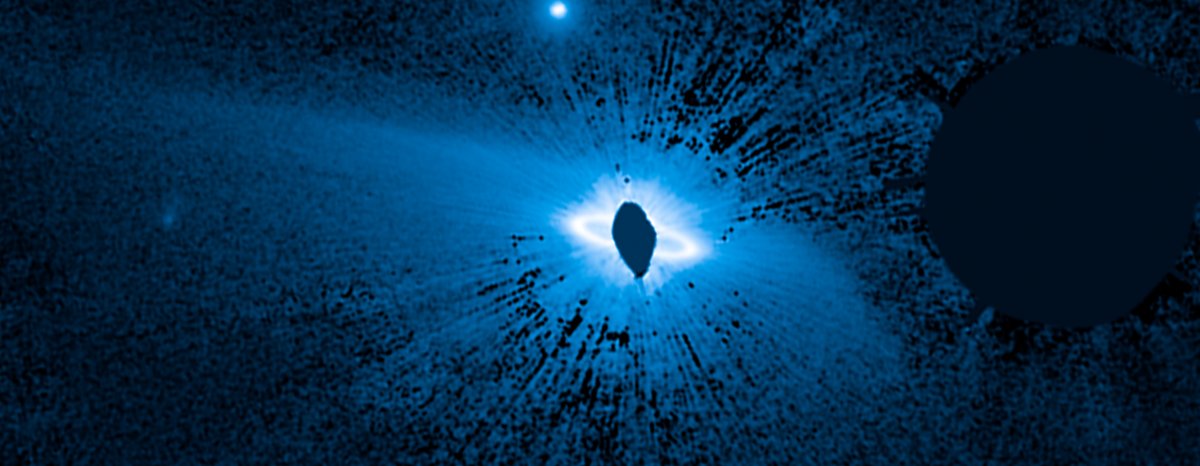

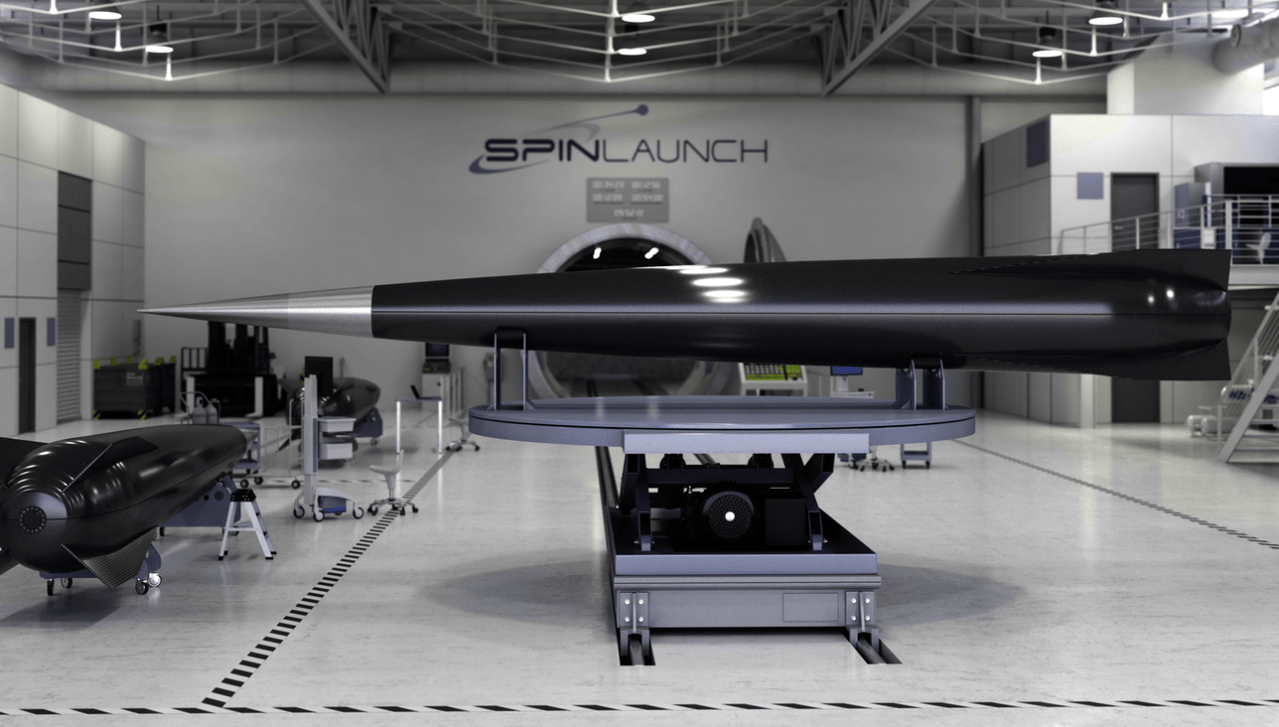

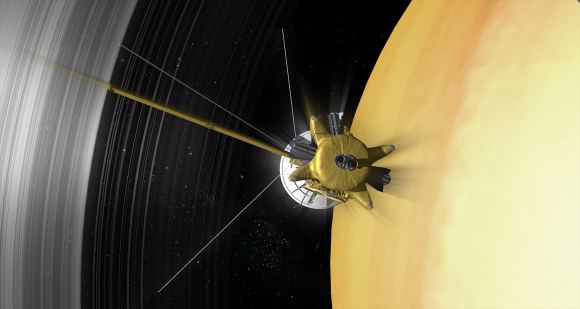

One of NASA’s proposals for dealing with an incoming asteroid is getting a lot of attention right now. It’s called the Hyper-velocity Asteroid Mitigation Mission for Emergency Response, or HAMMER. HAMMER is just a concept right now, but it’s worth talking about. It involves the use of a nuclear weapon to destroy any asteroid heading our way.

The use of a nuclear weapon to destroy or deflect an asteroid seems a little risky at first glance. They’re really a weapon of last resort here on Earth, because of their potential to wreck the biosphere. But out in space, there is no biosphere. If scientists sound a little glib when talking about HAMMER, the reality is they’re not. It makes perfect sense. In fact, it may be the only sensible use for a nuclear weapon.

The idea behind HAMMER is pretty simple; it’s a spacecraft with an 8.8 ton tip. The tip is either a nuclear weapon, or an 8.8 ton kinetic impactor. Once we detect an asteroid on a collision course with Earth, we use space-based and ground-based systems to ascertain its size. If its small enough, then HAMMER will not require the nuclear option. Just striking a small asteroid with sufficient mass will divert it away from Earth.

If the incoming asteroid is larger, or if we don’t detect it early enough, then the nuclear option is chosen. HAMMER would be launched with an atomic warhead on it, and the incoming offender would be destroyed. It sounds like a pretty tidy solution, but it’s a little more complicated than that.

A lot depends on the size of the object and when it’s detected. If we’re threatened by an object we’ve been aware of for a long time, then we might have a pretty good idea of its size, and of its trajectory. In that case, we can likely divert it with a kinetic impactor.

But for larger objects, we might require a fleet of impactors already in space, ready to be sent on a collision course. Or we might use the nuclear option. The ER in HAMMER stands for Emergency Response for a reason. If we don’t have enough time to plan or respond, then a system like HAMMER could be built and launched relatively quickly. (In this scenario, relatively quickly means years, not months.)

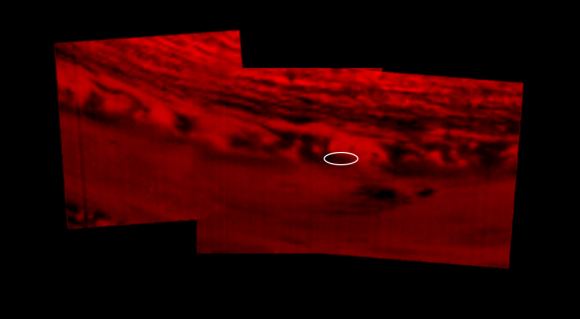

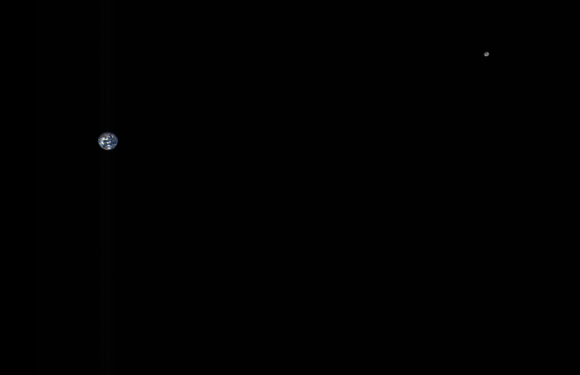

One of the problems is with the asteroids themselves. They have different orbits and trajectories, and the time to travel to different NEO‘s can vary widely. And things in space aren’t static. We share a region of space with a lot of moving rocks, and their trajectories can change as a result of gravitational interactions with other bodies. Also, as we learned from the arrival of Oumuamua last year, not all threats will be from our own Solar System. Some will take us by surprise. How will we deal with those? Could we deploy HAMMER quickly enough?

Another cautionary factor around using nukes to destroy asteroids is the risk of fracturing them into multiple pieces without destroying them. If an object larger than 1 km in diameter threatened Earth, and we aimed a nuclear warhead at it but didn’t destroy it, what would we do? How would we deal with one or more fragments heading towards Earth?

HAMMER and the whole issue of dealing with threatening asteroids is a complicated business. We’ll have to prepare somehow, and have a plan and systems in place for preventing collisions. But our best bet might lie in better detection.

We’ve gotten a lot better at detecting Near Earth Objects,(NEOs), Potentially Hazardous Objects (PHOs), and Near Earth Asteroids (NEAs) lately. We have telescopes and projects dedicated to cataloguing them, like Pan-STARRS, which discovered Oumuamua. And in the next few years, the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) will come online, boosting our detection capabilities even further.

It’s not just extinctions that we need to worry about. Asteroids also have the potential to cause massive climate change, disrupt our geopolitical order, and generally de-stabilize everything going on down here on Earth. At some point in time, an object capable of causing massive damage will speed toward us, and we’ll either need HAMMER, or another system like it, to protect ourselves and the planet.