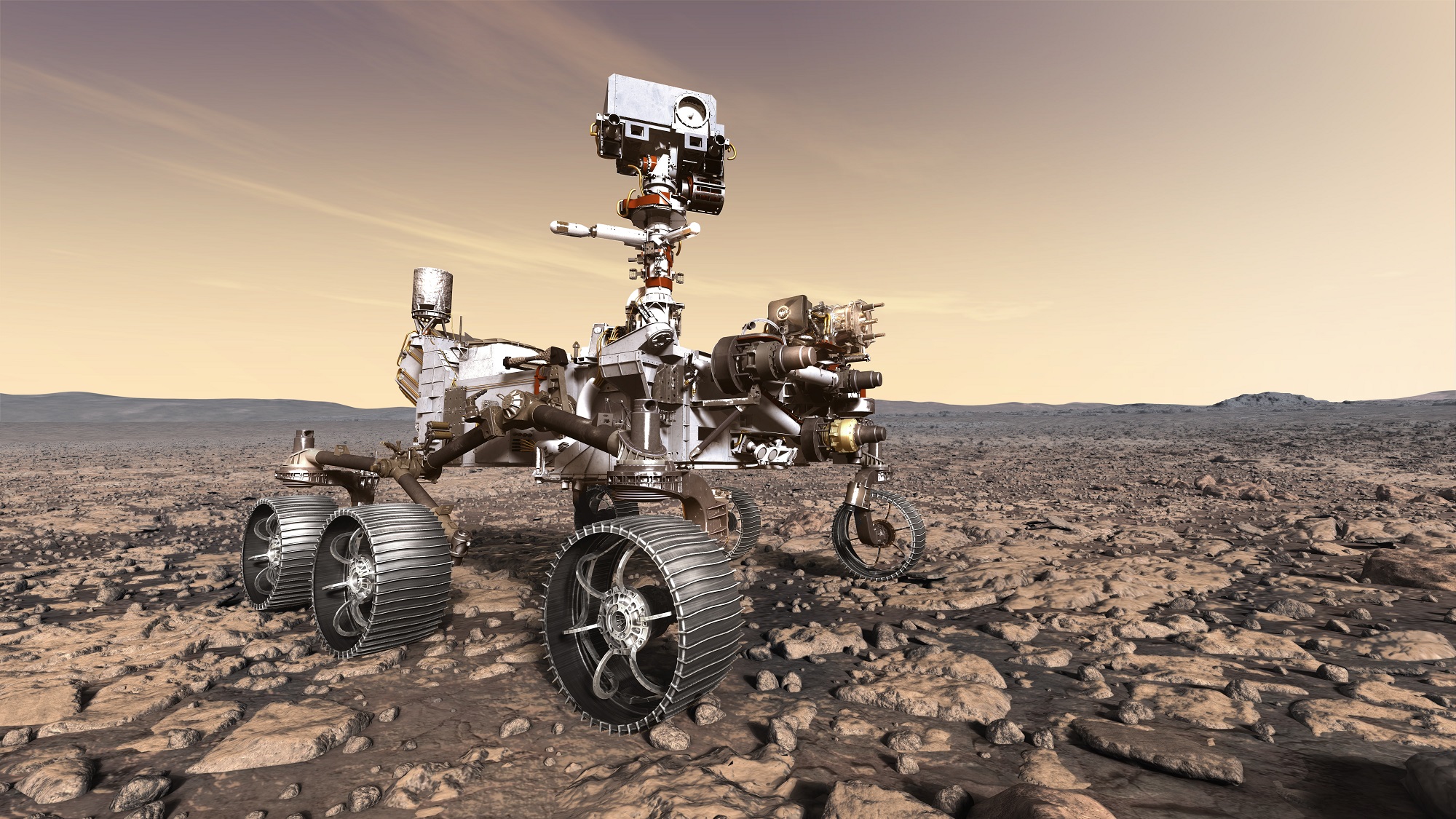

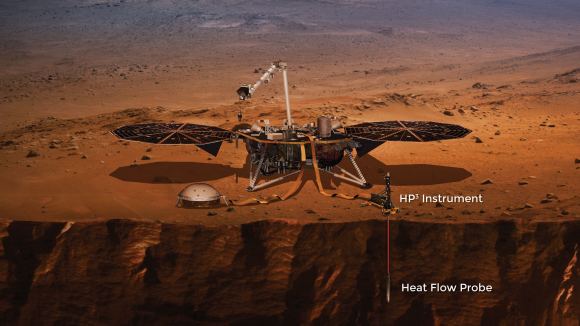

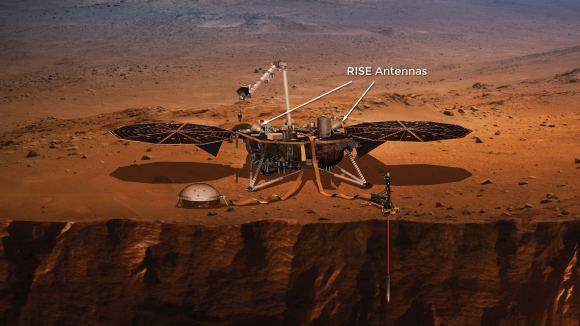

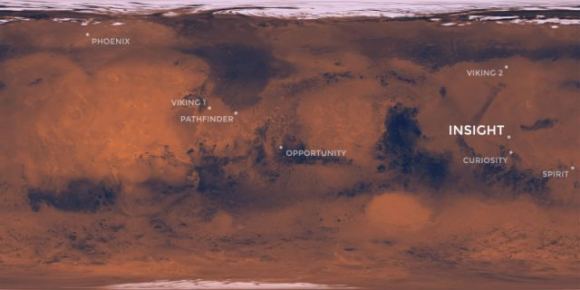

In July of 2020, the Mars 2020 rover – the latest from NASA’s Mars Exploration Program – will begin its long journey to the Red Planet. Hot on the heels of the Opportunity and Curiosity rovers, the Mars 2020 rover will attempt to answer some of the most pressing questions we have about Mars. Foremost among these is whether or not the planet had habitable conditions in the past, and whether or not microbial life existed there.

To this end, the Mars 2020 rover will obtain drill samples of Martian rock and set them aside in a cache. Future crewed missions may retrieve these samples and bring them back to Earth for analysis. However, in a recent announcement, NASA indicated that a piece of a Martian meteor will accompany the Mars 2020 rover back to Mars, which will be used to calibrate the rover’s high-precious laser scanner.

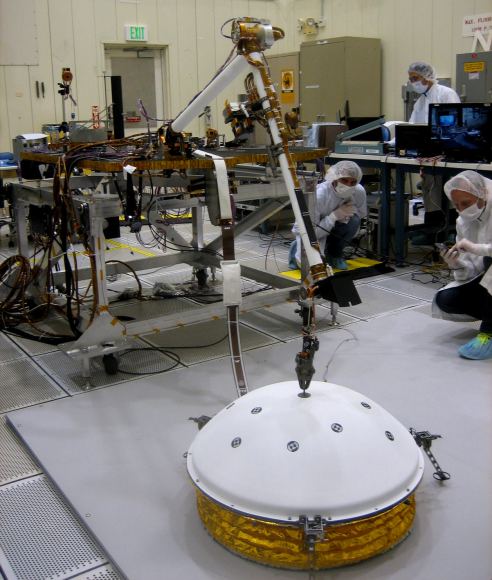

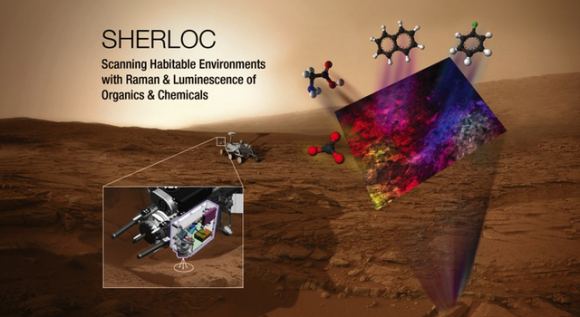

This laser scanner is known as the Scanning Habitable Environments with Raman and Luminescence for Organics and Chemicals (SHERLOC) instrument. The laser’s resolution is capable of illuminating even the finest features in rock samples, which could include fossilized microorganisms. But in order to achieve this, the laser requires a calibration target so that the science team can fine-tune its settings.

Ordinarily, these calibration targets involve pieces of rock, metal or glass, samples that are the result of a complex geological history. However, when addressing the SHERLOC’s calibration needs, JPL scientists came up with a rather innovative idea. For billions of years, Mars has experienced impacts that have sent pieces of its surface into orbit. In some cases, those pieces came to Earth in the form of meteorites, some of which have been identified.

While these meteorites are rare and not identical to the geologically diverse samples the Mars 2020 rover will collect, they are well-suited for target practice. As Luther Beegle of JPL, the principle investigator for SHERLOC, said in a recent NASA press statement:

“We’re studying things on such a fine scale that slight misalignments, caused by changes in temperature or even the rover settling into sand, can require us to correct our aim. By studying how the instrument sees a fixed target, we can understand how it will see a piece of the Martian surface.”

In this respect, the Mars 2020 rover is in good company. For example, Curiosity’s used its Chemistry and Camera (ChemCham) instrument – which relies on laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) – to determine the elemental compositions of rock and soil samples it has obtained. Similarly, the Opportunity rover’s Miniature Thermal Emission Spectrometer (Mini-TES) allowed this rover to detect the composition of rocks from a distance.

However, SHERLOC is unique in that it will be the first instrument deployed to Mars that uses Raman and fluorescence spectroscopy. Raman spectroscopy consists of subjecting materials to light in the visible, near infrared, or near ultraviolet range and measuring how the photons respond. Based on how their energy levels shift up or down, scientists are able to determine the presence of certain elements.

Fluorescence spectroscopy relies on ultraviolet lasers to excite the electrons in carbon-based compounds, which causes chemicals that are known to form in the presence of life (i.e. biosignatures) to glow. SHERLOC will also photograph the rocks it studies, which will allow the science team to map the chemical signatures it finds across the surface of Mars.

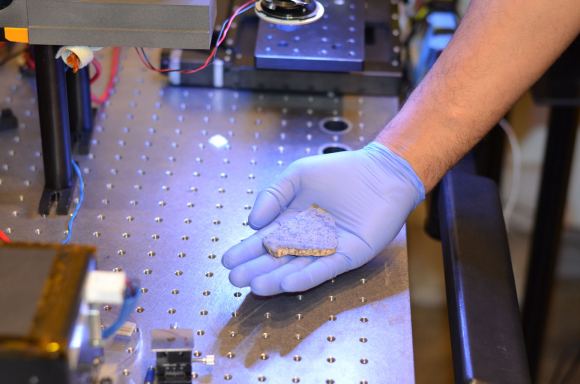

For their purposes, the SHERLOC team needed a sample that would be solid enough to withstand the intense vibrations caused by launch and landing. They also needed one that contained the right chemicals to test SHERLOC’s sensitivity to biosignatures. With the help of the Johnson Space Center and the Natural History Museum in London, they ultimately decided on a sample from the Sayh al Uhaymir 008 meteorite (aka. SaU008).

This meteorite, which was found in Oman in 1999, was more rugged that other samples and could be sliced without the rest of the meteorite flaking. As a result, SaU008 will be the first Martian meteorite sample that helps scientists look for past signs of life on Mars. It will also be the first Martian meteorite to have a piece of itself returned to the surface of Mars – though technically not the first to be sent back.

That honor goes to Zagami, a meteorite retrieved in Nigeria in 1962, which had a piece of itself sent back to Mars aboard the Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) in 1999. That mission ended in 2007, so this chunk has been floating around in orbit of Mars ever since. In addition, the team behind Mars 2020‘s SuperCam instrument will also be adding a Martian meteorite for their own calibration tests.

Along with bits of SaU008, the Mars 2020 payload will include samples of advanced materials. Aside from also being used to calibrate SHERLOC, these materials will be tested to see how they hold up to Martian weather and radiation. If they prove to be tough enough to survive on the Martian surface, these materials could be used in the manufacture of space suits, gloves and helmets for future astronauts.

As Marc Fries, a SHERLOC co-investigator and curator of extraterrestrial materials at Johnson Space Center, put it:

“The SHERLOC instrument is a valuable opportunity to prepare for human spaceflight as well as to perform fundamental scientific investigations of the Martian surface. It gives us a convenient way to test material that will keep future astronauts safe when they get to Mars.”

With every robotic mission sent to Mars, NASA and other space agencies are working towards the day when astronauts’ boots will finally touch down on the Red Planet. When the first crewed mission to Mars are conducted (currenty scheduled for the 2030s), they will be following in the tracks of some truly intrepid robotic explorers!

Further Reading: NASA