Considerable effort goes into the design of space suits and space agencies across the world are always working on improvements to enhance safety and mobility of the designs. NASA is now working with Collins Aerospace to develop their next generation spacesuit for the International Space Station. The new designs are tested extensively and recently, the new design was subjected to a ZeroG flight on board a diving aircraft.

Continue reading “Next Generation Spacesuit Gets Tested in Weightlessness”Gallery: Diving For Spacewalks Is Way Tougher Than You Think

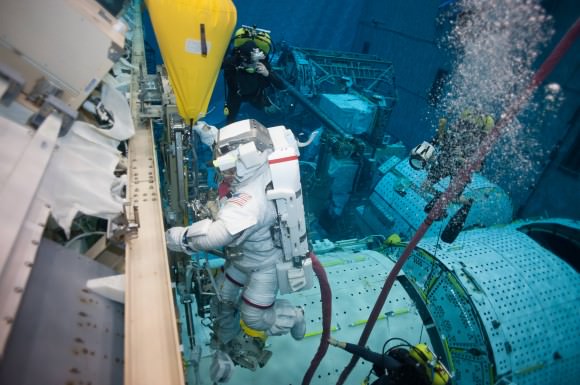

If you’ve spent any length of time underwater, you appreciate just how much drag it creates on your limbs — especially if you’re wearing a little clothing or carrying around diving equipment. Now, try to imagine using a pressurized spacesuit in that environment. You’re already puffed up like a balloon and have the drag to contend with.

Few of us will get that experience — NASA won’t let just anybody try on an expensive suit — but luckily for us, a person saying he is a diver (identifying himself only as Zugzwang5) posted about the experience on Reddit. The pictures alone are incredible, but the insights the diver provides show just how tough an astronaut has to be to get ready for spacewalking.

Using the spacesuit compared to a wetsuit, wrote Zugzwang 5 on Reddit, was “incredibly cumbersome”. He says he’s a contracted diver for Oceaneering working at NASA’s Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory in Houston, which has a model of the International Space Station in a huge pool for astronauts to practice spacewalking. Usually he’s inside a wetsuit, but the spacesuit was a completely different experience, he said.

There’s so much resistance from the suit and the water every motion takes tremendous effort. You might not guess it from my pictures, but I’m actually pretty fit, and I was exhausted by the end of the day. The hardest thing to get used to was moving up and down in the water column. I’ve been diving so long controlling my buoyancy is basically a force of will at this point, having to actually crawl and direct myself up and down was such a weird feeling.

Near the end of the marathon session, the diver had to bring back a simulated “incapacitated” astronaut to the airlock underwater, which he wrote was an extremely difficult task — especially while so tired.

So, for a real astronaut to pass their final evaluation they have to do a flawless incapacitated crew member rescue. this is actually very difficult as safely manipulating another suit is even more tiring and cumbersome than just moving your own. not only that but the airlock is very small, and safely (using proper tether technique) hooking someone else up into it is a surprisingly complex procedure where you have zero extra space to work with. Thirty minutes usually ends up being hardly enough time for the new guys, and even a vet will take more than 20.

You can check out the entire gallery at this link. Also, look at a past one the diver posted about the spacesuit fitting.

Astronaut Does A ‘Moon’ Walk In The Sea. Better Yet, It’s Just One Of Many Recent Underwater Missions

The black-and-white tones of this photo evoke a famous Moon walk of 1969, but in reality it was taken in Mediterranean waters just a few days ago.

For the “Apollo 11 Under The Sea” project, European Space Agency astronaut Jean-François Clervoy (pictured above) and ESA astronaut instructor Hervé Stevenin took on the roles of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, the first two men to walk on the moon during Apollo 11.

A major goal was to test the Comex-designed Gandolfi spacewalk training suit (based on the Russian Orlan spacesuits) during the sojourn. The mission was considered the first step (literally and figuratively) to figuring out how Europeans can train their astronauts for possible Moon, asteroid and Mars missions in the decades to come.

“The Gandolfi suit is bulky, has limited motion freedom, and requires some physical effort – just like actual space suits. I really felt like I was working and walking on the Moon,” Clervoy stated.

Even the photos come pretty darn close to the real thing. Compare this picture of Apollo 12 commander Pete Conrad during his Moon walk in 1969:

Water is considered a useful training tool for spacewalk simulations. NASA in fact has a ginormous pool called the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory. Inside are duplicate International Space Station modules. Astronauts are fitted with weights and flotation devices to make them “float” similarly to how they would during spacewalks.

With trained divers hovering nearby, the astronauts practice the procedures they’ll need so that it’s second nature by the time they get into orbit. (NASA astronaut Mike Massimino once told Universe Today that one thing he wasn’t prepared for was how spectacular the view was during his spacewalk. Guess it beats the walls of a pool.)

The first tests for the Apollo 11 underwater simulations began at a pool run by Comex, a deep diving specialist in France, before the big show took place in the Mediterranean Sea off Marseille on Sept. 4. The crew members used tools similar to the Apollo 11 astronauts to pick up soil samples from the ground.

“Comex will make me relive the underwater operations of [Neil] Armstrong on the moon, but with an ESA-Comex scuba suit and European flag,” Clervoy wrote in French on Twitter on June 4, several weeks ahead of the mission.

And ESA promises there is more to come: “Further development for planetary surface simulations in Europe will be co-financed by the EU [European Union] as part of the Moonwalk project,” the agency wrote.

Clervoy isn’t the only European astronaut working in water these days. Starting Tuesday (Sept. 9), Andreas Mogensen and Thomas Pesquet joined an underwater lab as part of a five-person crew. Called Space Environment Analog for Testing EVA Systems and Training (SEATEST), it also includes NASA astronauts Joe Acaba and Kate Rubins, as well as Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) astronaut Soichi Noguchi.

“The crew will spend five days in Florida International University’s Aquarius Reef Base undersea research habitat, conducting proof-of-concept engineering demonstrations and refining techniques in team communication. Additional test objectives will look at just-in-time training applications and spacewalking tool designs,” NASA stated on Sept. 6.

“We made it to Aquarius n [sic] did our first “spacewalk” today. From the ocean floor to space: Aquanaut to Astronaut. It is quite the adventure,” Acaba wrote on Twitter on Sept. 10. He walked twice in space on shuttle mission STS-119 in March 2009.

You can follow the livestream here (it runs intermittently until Sept. 17).

And a few days ago, ESA astronauts Alexander Gerst and Reid Wiseman, both bound for the station in 2014, were doing underwater training in the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory. “Worked with @astro_reid in the pool today, and guess who we met?”, Gerst said on Twitter Sept. 5 while posting this picture below.

!["Worked with @astro_reid [ESA astronaut Reid Wiseman] in the pool today, and guess who we met?" joked ESA astronaut Alexander Gerst on Twitter on Sept. 5, 2013. Presumably the joke referred to the protagonist in WALL-E, a 2008 Pixar-animated film that features space exploration. Credit: Alexander Gerst/Twitter](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/NBL_shot-433x580.jpg)

The Ocean is a lot Like Outer Space

Just about any space mission these days requires water training. Think of the countless hours astronauts spend in the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory at the Johnson Space Center, practicing the steps to do spacewalks. Then there are the crews that actually live in the ocean for days at a time on NASA’s NEEMO missions.

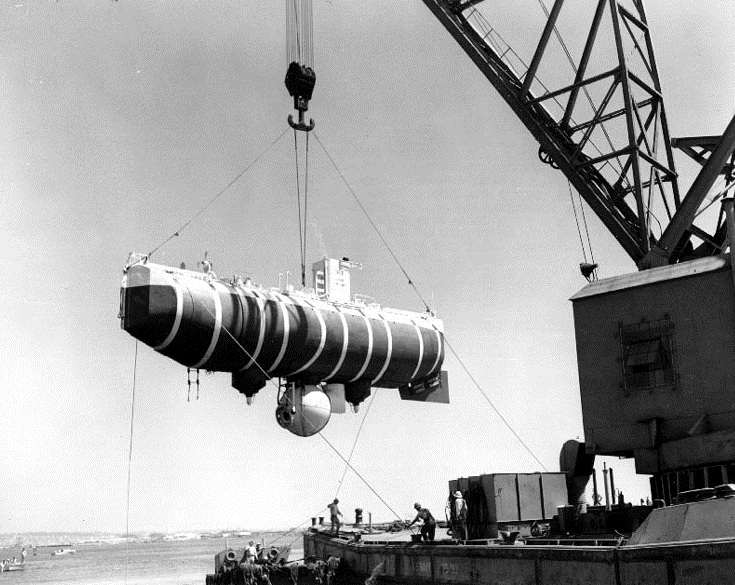

Long before these “aquanauts” added flippers to their list of equipment, however, the U.S. Navy was busy exploring the depths of the ocean. Today – Jan. 23 – marks the anniversary of the Bathyscaphe Trieste’s descent to the bottom of the ocean in 1960. This was the first time a vessel, manned or unmanned, had reached the deepest known point of the Earth’s oceans, the Mariana Trench.

Trieste was at first operated by the French Navy, which operated it for several years in the Mediterranean Sea, but the US Navy purchased the Trieste in 1958.

Although two men took the ride down, all accounts say that it was an isolating experience. Jacques Piccard – well-known today for his exploration of the oceans – and US Navy Lieutenant Don Walsh descended about 11 kilometers (7 miles) to the bottom.

Fighting with poor communications and high pressure – which cracked a window at 30,000 feet below the surface – the crew made their way to ocean floor. They worked in a tiny sphere only 2 meters (6.5 feet) wide, and according to the University of Delaware, the interior reached frigid temperatures of 7 degrees Celsius (45 degrees Fahrenheit) during their successful descent and return.

Spaceflight and deep-ocean diving share many similarities, as this mission demonstrated. The early days of the space program had communications blackouts as spaceships flew between stations; this proved to be a near-disaster for the Gemini 8 crew in 1966 when their spacecraft spun out of control during a period with no voice connection to the ground.

Also, sustaining life is no less challenging in the water as it is in space. Humans require oxygen, pressure and a comfortable environment where they work. Crews in space have faced serious problems with all of these matters before – Mir suffered a partial depressurization in 1997, and the early days of the Skylab space station were rather hot until the astronauts could deploy a sunshade.

Walsh was not available for an interview with Universe Today due to travel, but in a 2012 BBC interview he noted that he had reserved confidence that they would make it to the bottom.

“I knew the machine well enough, at that point, to know that theoretically, it could be done,” Walsh recalled.

The mens’ feat would go unrepeated for decades, until in 2012 Hollywood director James Cameron made the descent again – alone, although certainly equipped with more modern technology. For comparison, only one American has flown solo in space since the 1960s; in 2004, Mike Melvill piloted SpaceShipOne into suborbital space twice as part of the Ansari X-Prize win.