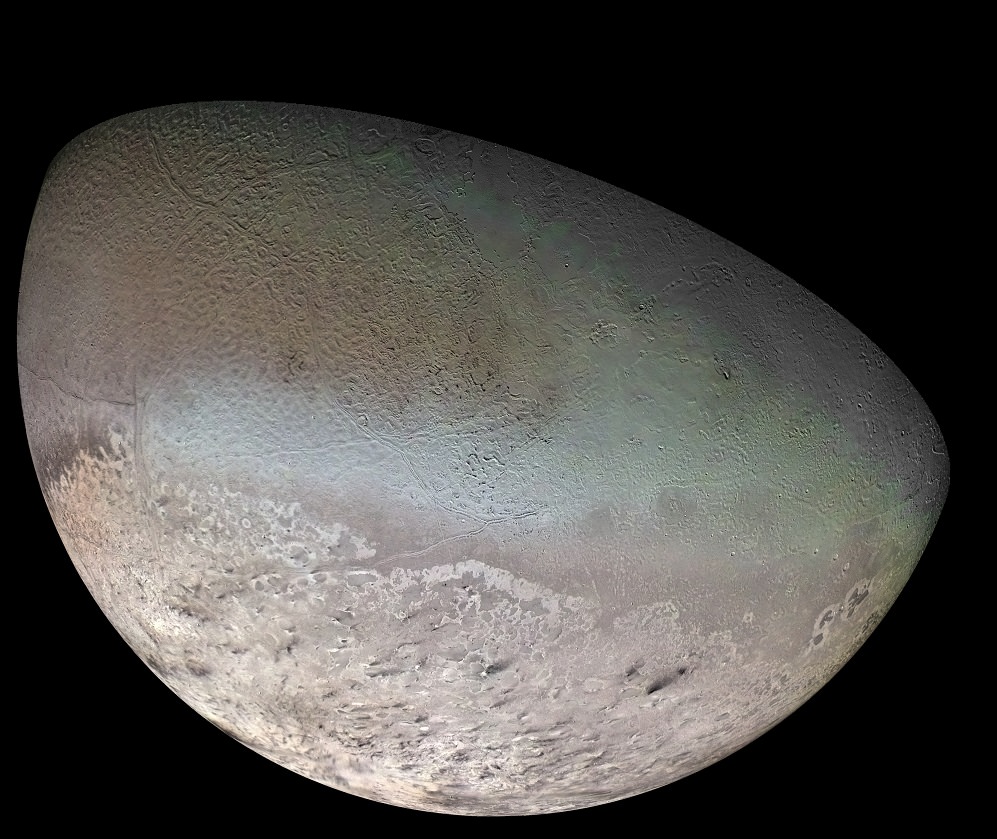

The planets of the outer Solar System are known for being strange, as are their many moons. This is especially true of Triton, Neptune’s largest moon. In addition to being the seventh-largest moon in the Solar System, it is also the only major moon that has a retrograde orbit – i.e. it revolves in the direction opposite to the planet’s rotation. This suggests that Triton did not form in orbit around Neptune, but is a cosmic visitor that passed by one day and decided to stay.

And like most moons in the outer Solar System, Triton is believed to be composed of an icy surface and a rocky core. But unlike most Solar moons, Triton is one of the few that is known to be geologically active. This results in cryovolcanism, where geysers periodically break through the crust and turn the surface Triton into what is sure to be a psychedelic experience!

Discovery and Naming:

Triton was discovered by British astronomer William Lassell on October 10th, 1846, just 17 days after the discovery of Neptune by German astronomer Johann Gottfried Galle. After learning about the discovery, John Herschel – the son of famed English astronomer William Herschel, who discovered many of Saturn’s and Uranus’ moons – wrote to Lassell and recommended he observe Neptune to see if it had any moons as well.

Lassell did so and discovered Neptune’s largest moon eight days later. Thirty-four years later, French astronomer Camille Flammarion named the moon Triton – after the Greek sea god and son of Poseidon (the equivalent of the Roman god Neptune) – in his 1880 book Astronomie Populaire. It would be several decades before the name caught on however. Until the discovery of the second moon Nereid in 1949, Triton was commonly known simply as “the satellite of Neptune”.

Size, Mass and Orbit:

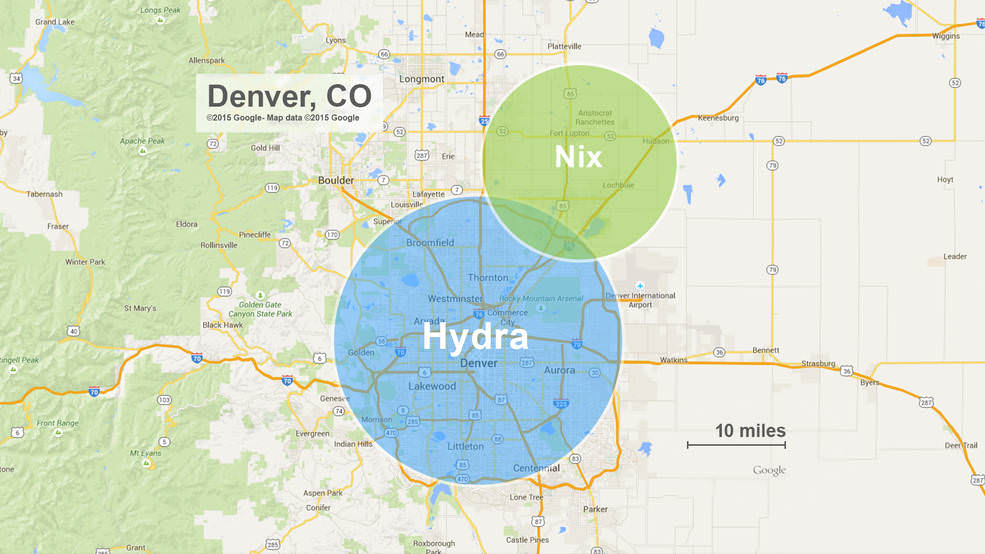

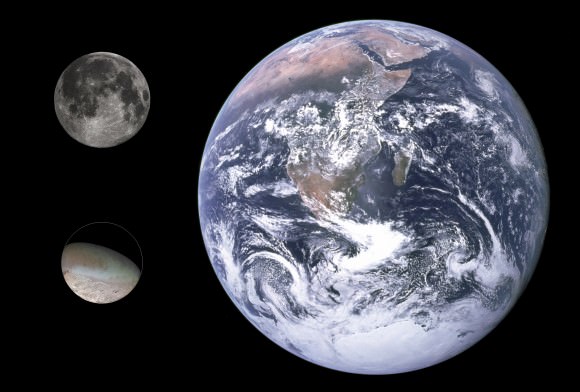

At 2.14 × 1022 kg, and with a diameter of approx. 2,700 kilometers (1,680 miles) km, Triton is the largest moon in the Neptunian system – comprising more than 99.5% of all the mass known to orbit the planet. In addition to being the seventh-largest moon in the Solar System, it is also more massive than all known moons in the Solar System smaller than itself combined.

With no axial tilt and an eccentricity of virtually zero, the moon orbits Neptune at a distance of 354,760 km (220,438 miles). At this distance, Triton is the farthest satellite of Neptune, and orbits the planet every 5.87685 Earth days. Unlike other moons of its size, Triton has a retrograde orbit around its host planet.

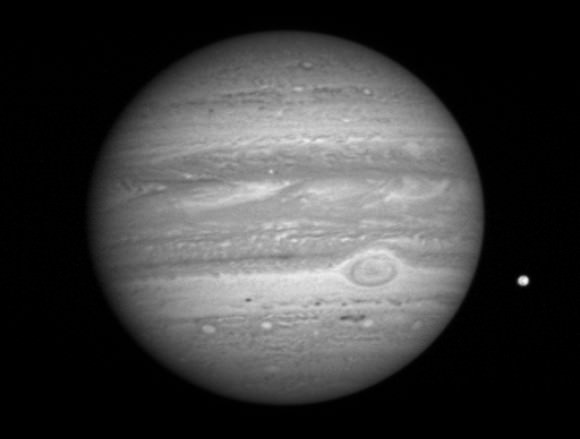

Most of the outer irregular moons of Jupiter and Saturn have retrograde orbits, as do some of Uranus’s outer moons. However, these moons are all much more distant from their primaries, and are rather small in comparison. Triton also has a synchronous orbit with Neptune, which means it keeps one face aimed towards the planet at all times.

As Neptune orbits the Sun, Triton’s polar regions take turns facing the Sun, resulting in seasonal changes as one pole, then the other, moves into the sunlight. Such changes were observed in April of 2010 by astronomers using the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope.

Another all-important aspect of Triton’s orbit is that it is decaying. Scientists estimate that in approximately 3.6 billion years, it will pass below Neptune’s Roche limit and will be torn apart.

Composition:

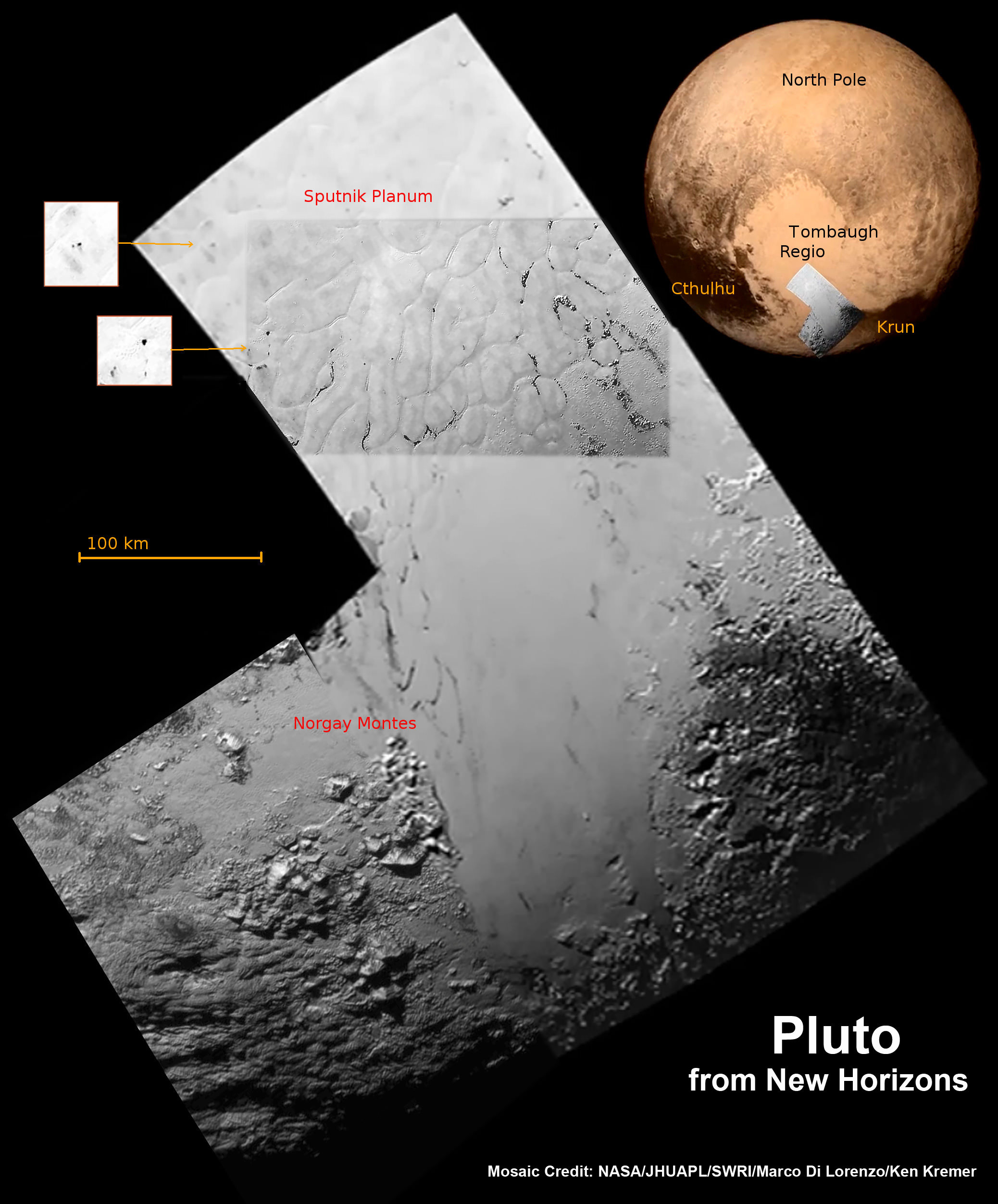

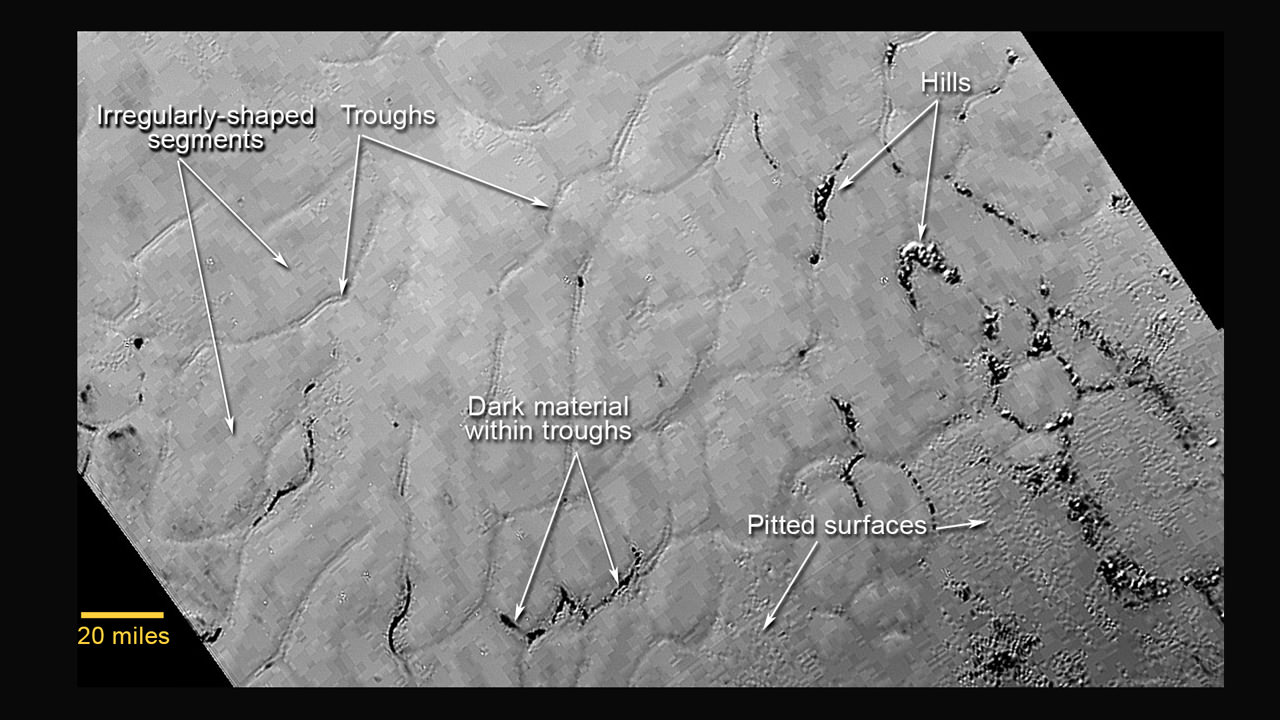

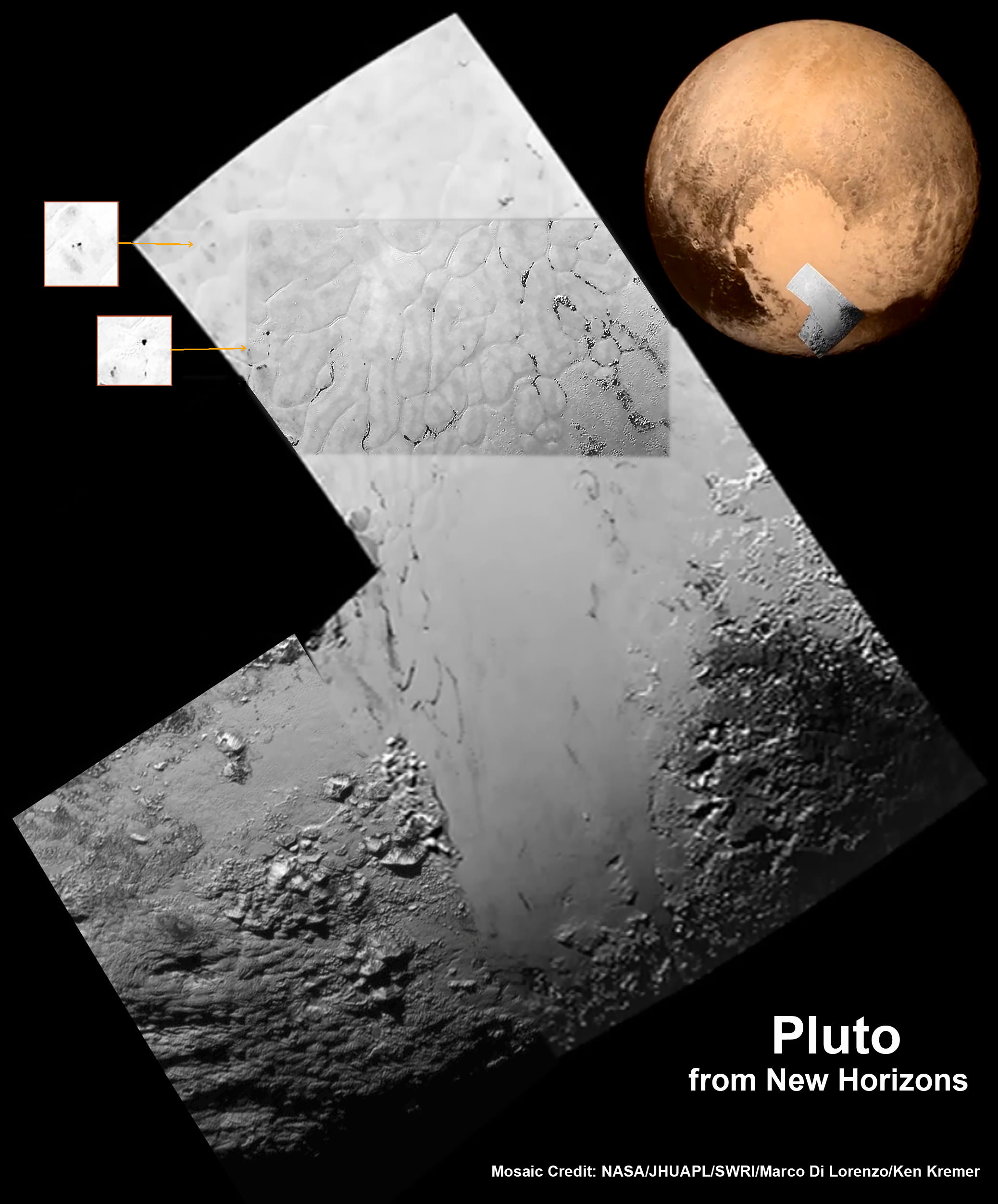

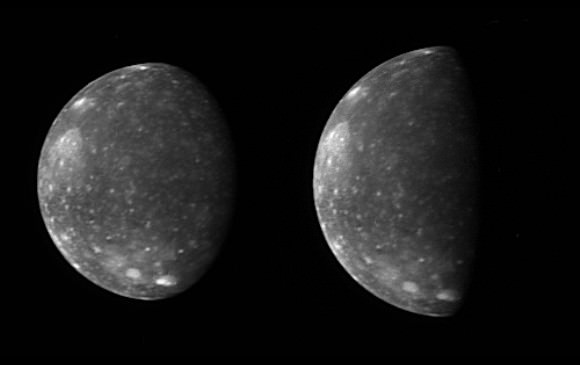

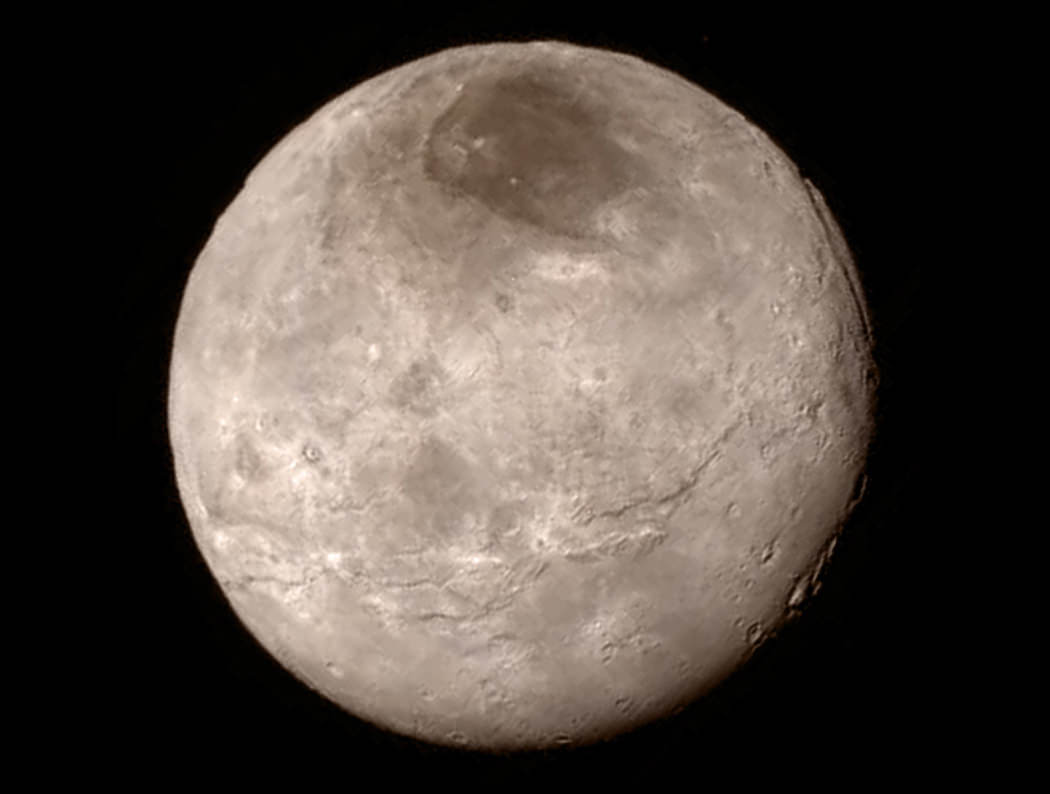

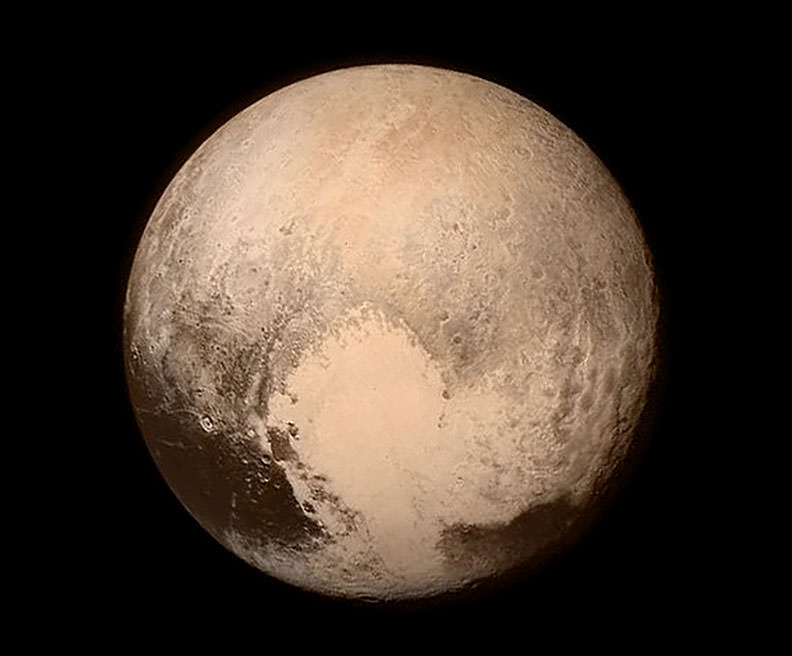

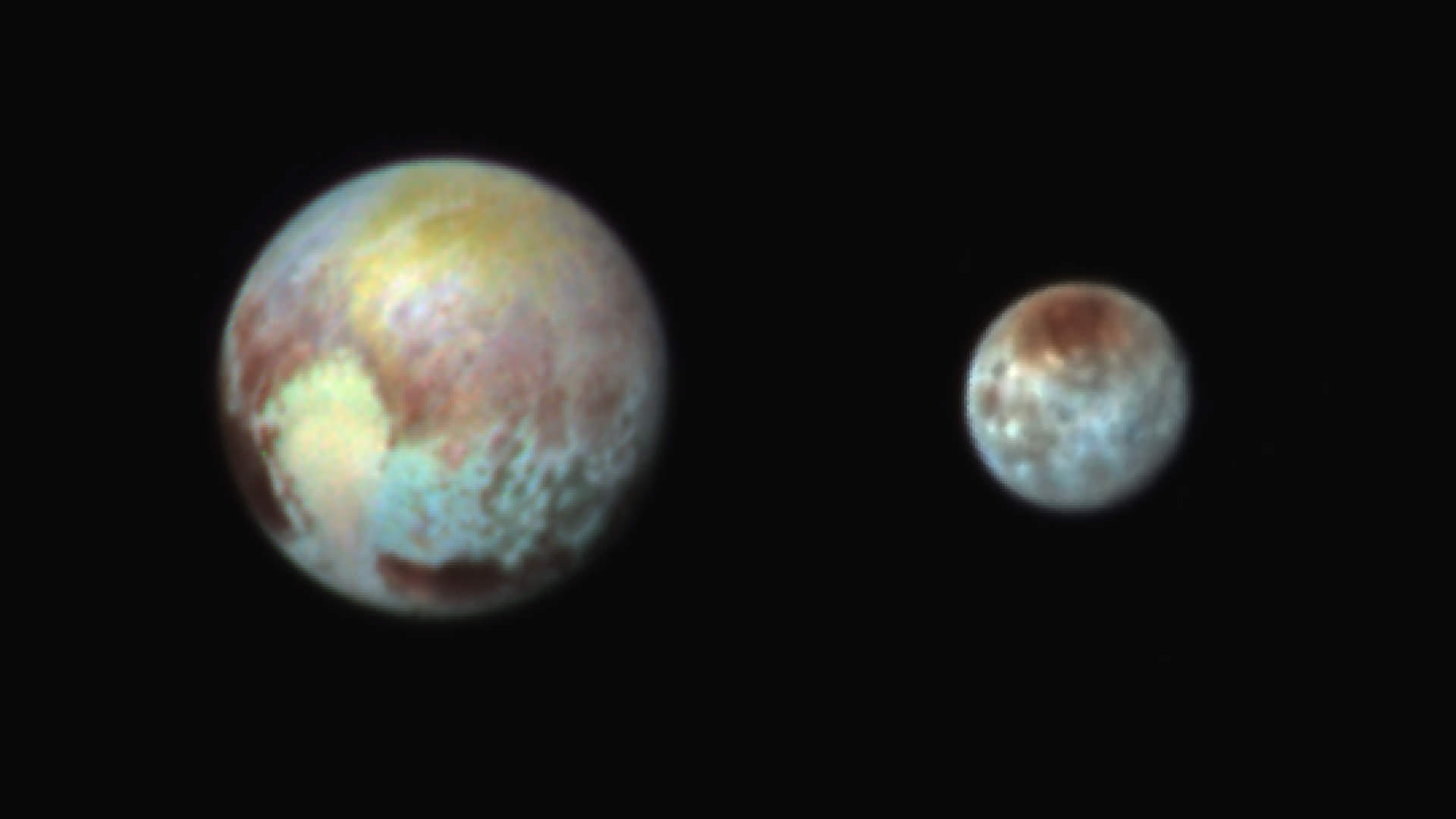

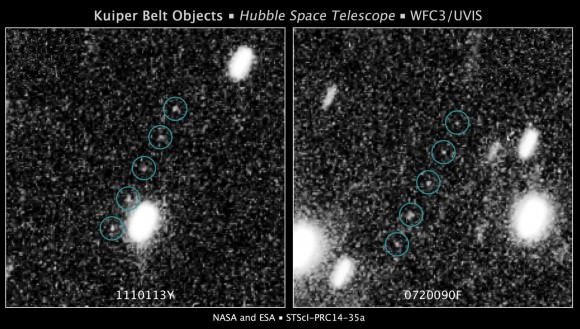

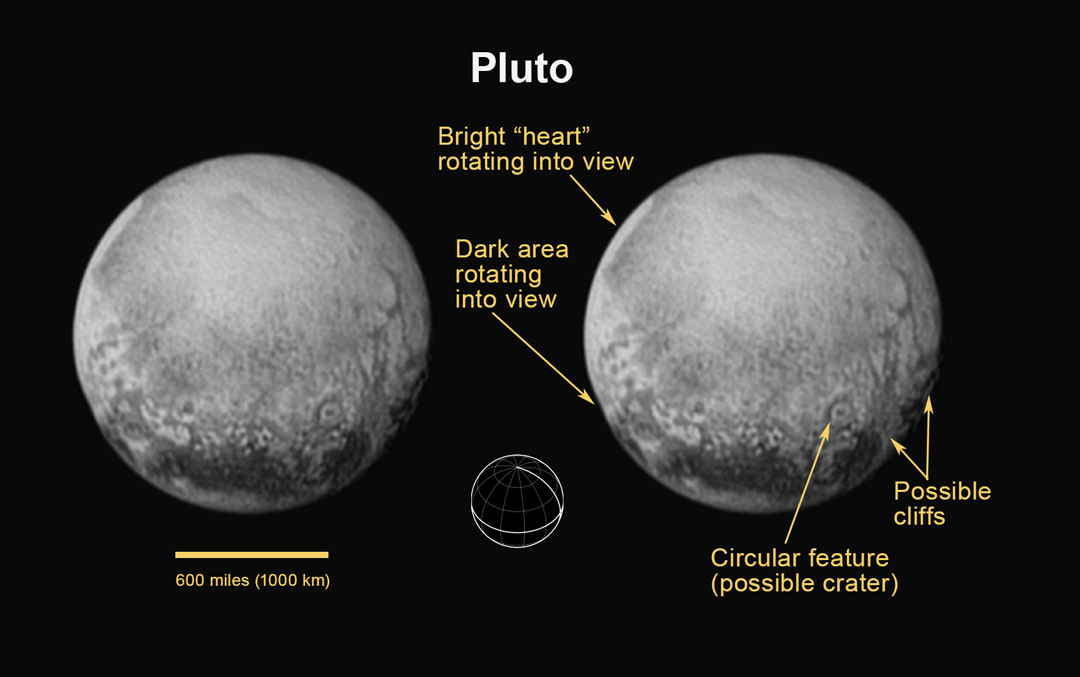

Triton has a radius, density (2.061 g/cm3), temperature and chemical composition similar to thatof Pluto. Because of this, and the fact that it circles Neptune in a retrograde orbit, astronomers believe that the moon originated in the Kuiper Belt and later became trapped by Neptune’s gravity.

Another theory has it that Triton was once a dwarf planet with a companion. In this scenario, Neptune captured Triton and flung its companion away when the giant gas moved further out into the solar system, billions of years ago.

Also like Pluto, 55% of Triton’s surface is covered with frozen nitrogen, with water ice comprising 15–35% and dry ice (aka. frozen carbon dioxide) forming the remaining 10–20%. Trace amounts of methane and carbon monoxide ice are believed to exist there as well, as are small amounts of ammonia (in the form of ammonia dihydrate in the lithosphere).

Triton’s density suggests that its interior is differentiated between a solid core made of rocky material and metals, a mantle composed of ice, and a crust. There is enough rock in Triton’s interior for radioactive decay to power convection in the mantle, which may even be sufficient to maintain a subterranean ocean. As with Jupiter’s moon of Europa, the proposed existence of this warm-water ocean could mean the presence of life beneath the icy crusts.

Atmosphere and Surface Features:

Triton has a considerably high albedo, reflecting 60–95% of the sunlight that reaches it. The surface is also quite young, which is an indication of the possible existence of an interior ocean and geological activity. The moon has a reddish tint, which is probably the result of the methane ice turning to carbon due to exposure to ultraviolet radiation.

Triton is considered to be one of the coldest places in the Solar System. The moon’s surface temperature is approx. -235°C while Pluto averages about -229°C. Scientists say that Pluto may drop as low as -240°C at the furthest point from the Sun in its orbit, but it also gets much warmer closer to the Sun, giving it a higher overall temperature average.

It is also one of the few moons in the Solar System that is geologically active, which means that its surface is relatively young due to resurfacing. This activity also results in cryovolcanism, where water ammonia and nitrogen gas burst forth from the surface instead of liquid rock. These nitrogen geysers can send plumes of liquid nitrogen 8 km above the surface of the moon.

Because of the geological activity constantly renewing the moon’s surface, there are very few impact craters on Triton. Like Pluto, Triton has an atmosphere that is thought to have resulted from the evaporation of ices from its surface. Like its surface ices, Triton’s tenuous atmosphere is made up of nitrogen with trace amounts of carbon monoxide and small amounts of methane near the surface.

This atmosphere consists of a troposphere rising to an altitude of 8km, where it then gives way to a thermosphere that reaches out to 950 km from the surface. The temperature of Triton’s upper atmosphere, at 95-100 K (ca.-175 °C/-283 °F) is higher than that at the surface, due to the influence of solar radiation and Neptune’s magnetosphere.

A haze permeates most of Triton’s troposphere, thought to be composed largely of hydrocarbons and nitriles created by the action of sunlight on methane. Triton’s atmosphere also has clouds of condensed nitrogen that lie between 1 and 3 km from the surface.

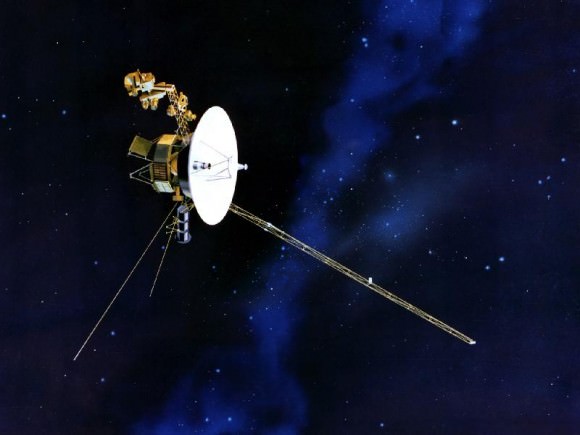

Observations taken from Earth and by the Voyager 2 spacecraft have shown that Triton experiences a warm summer season every few hundred years. This could be the result of a periodic change in the planet’s albedo (i.e. its gets darker and redder) which could be caused by either frost patterns or geological activity.

This change would allow more heat to be absorbed, followed by an increase in sublimation and atmospheric pressure. Data collected between 1987 and 1999 indicated that Triton was approaching one of these warm summers.

Exploration:

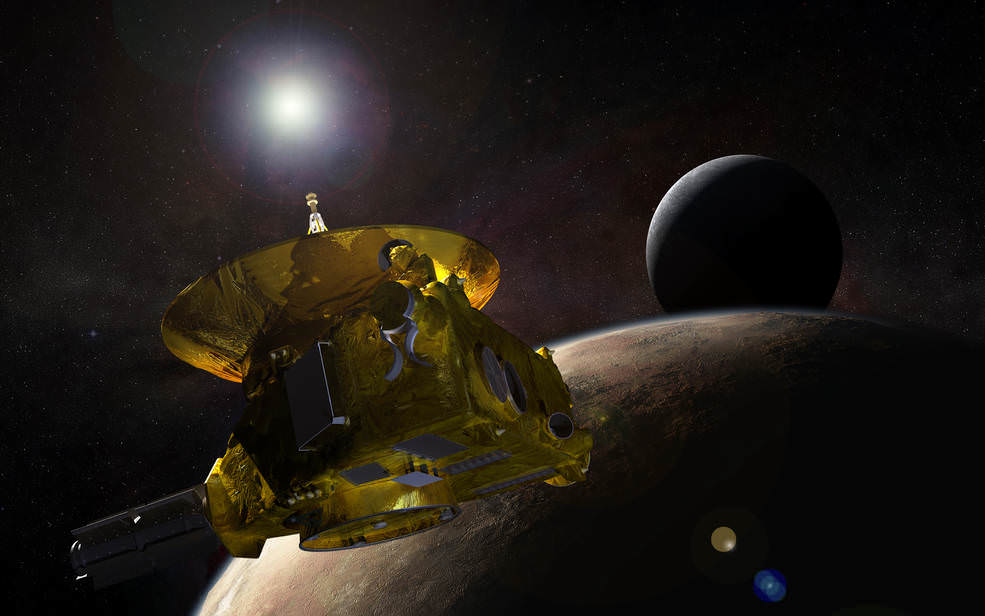

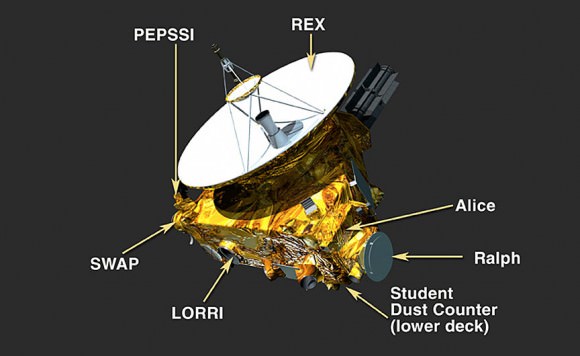

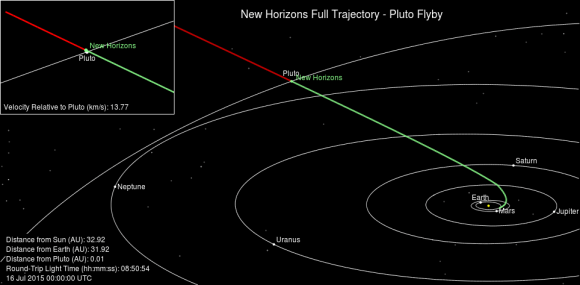

When NASA’s Voyager 2 made a flyby of Neptune in August of 1989, the mission controllers also decided to conduct a flyby of Triton – similar to Voyager 1‘s encounter with Saturn and Titan. When it made its flyby, most of the northern hemisphere was in darkness and unseen by Voyager.

Because of the speed of Voyager’s visit and the slow rotation of Triton, only one hemisphere was seen clearly at close distance. The rest of the surface was either in darkness or seen as blurry markings. Nevertheless, the Voyager 2 spacecraft managed to capture several images of the moon and spotted geysers of liquid nitrogen blasting out of two distinct features on the surface.

In August of 2014, in anticipation of New Horizons impending encounter with Pluto, NASA restored these photos and used them to create the first global color map of Triton. Produced by Paul Schenk, a scientist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, the map was also used to make a movie (shown below) that recreated the historic Voyager 2 encounter in time for the 25th anniversary of the event.

Yes, Triton is indeed an unusual moon. Aside from its rather unique characteristics (retrograde motion, geological activity) the moon’s landscape is likely to be an amazing sight. For anyone standing on the surface, surrounded by colorful ices, plumes of nitrogen and ammonia, a nitrogen haze and Neptune’s big blue disc hanging on the sky, the experience would seem like something akin to a hallucination.

In the end, it is too bad that the Solar System will one day be saying good-bye to this moon. Because of the nature of its orbit, the moon will eventually fall into Neptune’s gravity well and break up. At which point, Neptune will have a huge ring like Saturn, until those particles crash into the planet as well.

That too would be something to behold. One can only hope that humanity will still be around in 3.6 billion years to witness it!

We have many interesting articles on Triton, Neptune, and the outer planets of the Solar System here at Universe Today.

Here’s one about the New Map of Triton, and one about the Underground Ocean it might be hiding, and 40 Years of Summer on Triton. And here’s Why You Shouldn’t Buy Real Estate on Triton.

In the Observatory also has an interview with Emily Lakdawalla, the senior editor and planetary evangelist for the Planetary Society, titled “Where Should We Look for Life in the Solar System?”

Sources: