Welcome back to Constellation Friday! Today, in honor of the late and great Tammy Plotner, we will be dealing with the compass – the Circinus constellation!

In the 2nd century CE, Greek-Egyptian astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus (aka. Ptolemy) compiled a list of all the then-known 48 constellations. This treatise, known as the Almagest, would be used by medieval European and Islamic scholars for over a thousand years to come, effectively becoming astrological and astronomical canon until the early Modern Age.

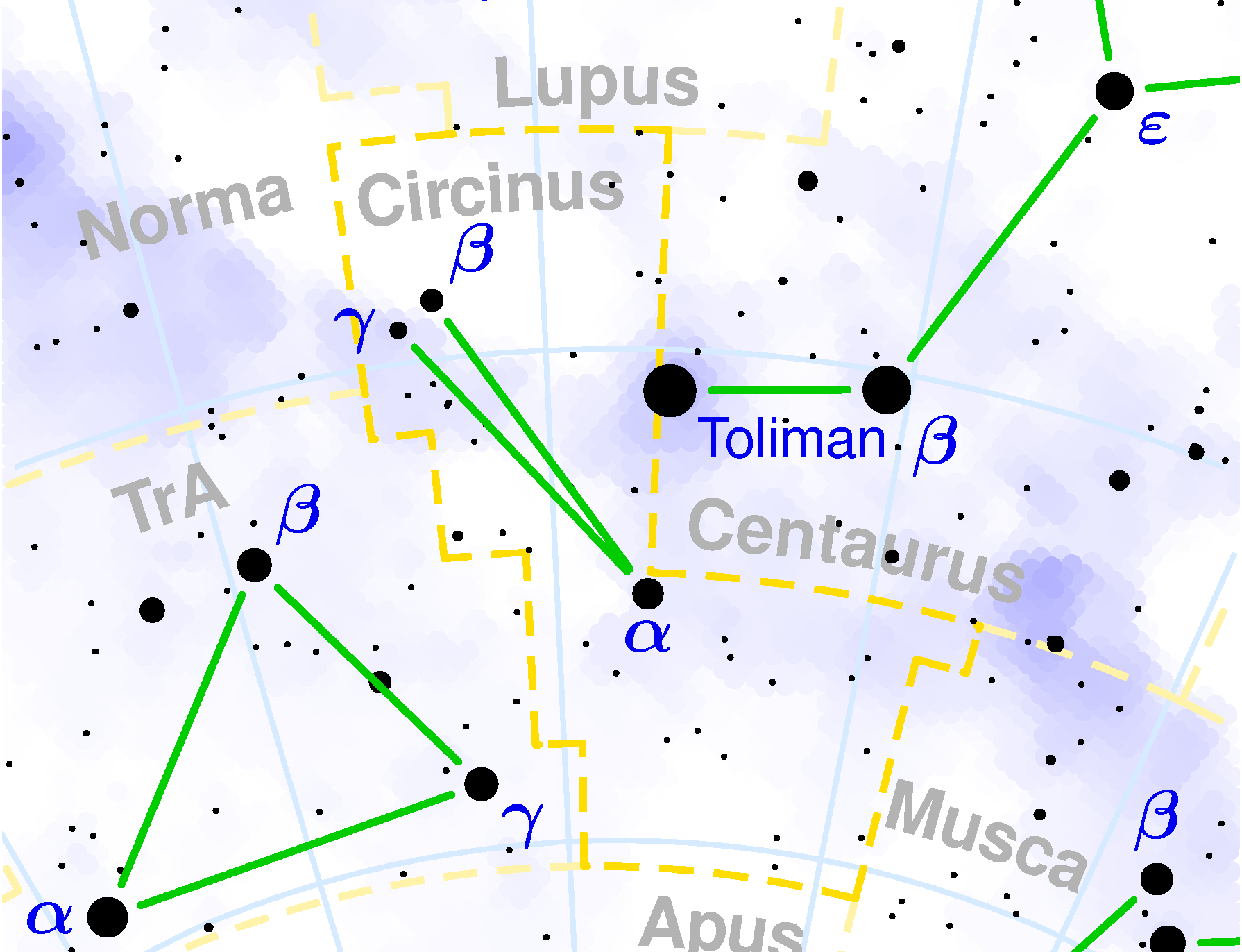

Over time, the number of recognized constellations has grown as astronomers and explorers became aware of other stars visible from other location around the world. By the 20th century, the IAU adopted a modern catalog of 88 Constellations. One of these is the Circinus constellation, a small, faint constellation located in the southern skies. It is bordered by the constellations Apus, Centaurus, Lupus, Musca, Norma, Triangulum Australe.

Name and Meaning:

Because Circinus was unknown to the ancient Greeks and Romans, it has no mythology associated with it. The three brightest stars form a narrow triangle. The shape is reminiscent of a drawing (or drafting) compass of the sort used to plot sea and sky charts. Nicolas Louis de Lacaille had a fascination with secular science and the thought of naming a constellation after a science tool fascinated him.

In this case, Circinus represents a drafting tool used in navigation, mathematics, technical drawing, engineering drawing, in cartography (drawing maps) – and which many elementary school age children use to learn to draw circles and in geometry to bi-sect lines, draw arcs and so forth. In this case, the device should not be confused with Pyxis, a constellation associated with a ship’s compass… despite the similarity in names with the Latin language!

History of Observation:

The small, faint southern constellation Circinus was created by Nicholas de Lacaille during his stay at the Cape of Good Hope in the mid-18th century. Circinus was given its current name in 1763, when Lacaille published an updated sky map with Latin names for the constellations he introduced.

On the map he created, Lacaille portrayed the constellations of Norma, Circinus, and Triangulum Australe as a set of draughtsman’s instruments – as a ruler, compass, and a surveyor’s level, respectively. This constellation has endured and became one of the 88 modern constellation recognized by the IAU in 1920.

Notable Features:

Circinus has no bright stars and consists of only 3 main stars and 9 Bayer/Flamsteed designated stars. However, the constellation does have several Deep Sky Objects associated with it. For instance, there’s the Circinus Galaxy, a spiral galaxy located approximately 13 million light years distant that was discovered in 1975. The galaxy is notable for the gas rings inside it, one of which is a massive star-forming region, and its black hole-powered core.

Then there’s the X-ray double star known as Circinus X-1, which is located approximately 30,700 light years away and was discovered in 1969. This system is composed of a neutron star orbiting a main sequence star. Circinus is also home to the bright planetary nebula known as NGC 5315, which was created when a star went supernova and cast off its outer layers into space.

Then there’s NGC 5823 (aka. Caldwell 88), an open cluster located on the border between Circinus and Lupus. Located about 3,500 light years away, this cluster is about 800 million years old and spans about 12 light years.

Finding Circinus:

Circinus is visible at latitudes between +10° and -90° and is best seen at culmination during the month of June. Start by taking out your binoculars for a look at Alpha Circini – a great visual double star. Located about 53.5 light years from Earth, this stellar pair isn’t physically related but does make a unique target. The brighter of the two, Alpha, is a F1 Bright Yellow Dwarf that is a slight variable star. This contrasts very nicely with the fainter, red companion.

For the telescope, take a look at Gamma Circini – a faint star a little over five hundred light years from the Solar System. In the sky, it lies in the Milky Way, between bright Alpha Centauri and the Southern Triangle. Gamma Circini is a binary system, containing a blue giant star with a yellow, F-type, companion. Gamma is unique because it possess a stellar magnetic buoyancy!

For larger binoculars and telescopes, have a look at galactic star cluster NGC 5823 (RA 15 : 05.7 Dec -55 : 36). This dim cluster will appear to have several brighter members which are actually foreground stars, but does include Mira-type variable Y Circini. While it will be hard to distinguish from the rich, Milky Way star fields, you will notice an elliptical shaped compression of stars with an asterism which resembles and open umbrella.

For large telescopes, check out ESO 97-G13 – the “Circinus Galaxy”. Located only 4 degrees below the Galactic plane, and 13 million light-years away (RA 14h 13m 9.9s Dec 65° 20? 21?), this Seyfert Galaxy is undergoing tumultuous changes, as rings of gas are being ejected from the galactic core. While it can be spotted in a small telescope, science didn’t notice it until 25 years ago!

We have written many interesting articles about the constellation here at Universe Today. Here is What Are The Constellations?, What Is The Zodiac?, and Zodiac Signs And Their Dates.

Be sure to check out The Messier Catalog while you’re at it!

For more information, check out the IAUs list of Constellations, and the Students for the Exploration and Development of Space page on Canes Venatici and Constellation Families.

Sources: