Supernovas are some of the most energetic and powerful events in the observable Universe. Briefly outshining entire galaxies, they are the final, dying outbursts of stars several times more massive than our Sun. And while we know supernovas are responsible for creating the heavy elements necessary for everything from planets to people to power tools, scientists have long struggled to determine the mechanics behind the sudden collapse and subsequent explosion of massive stars.

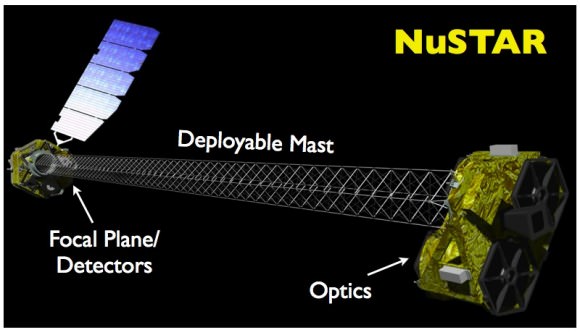

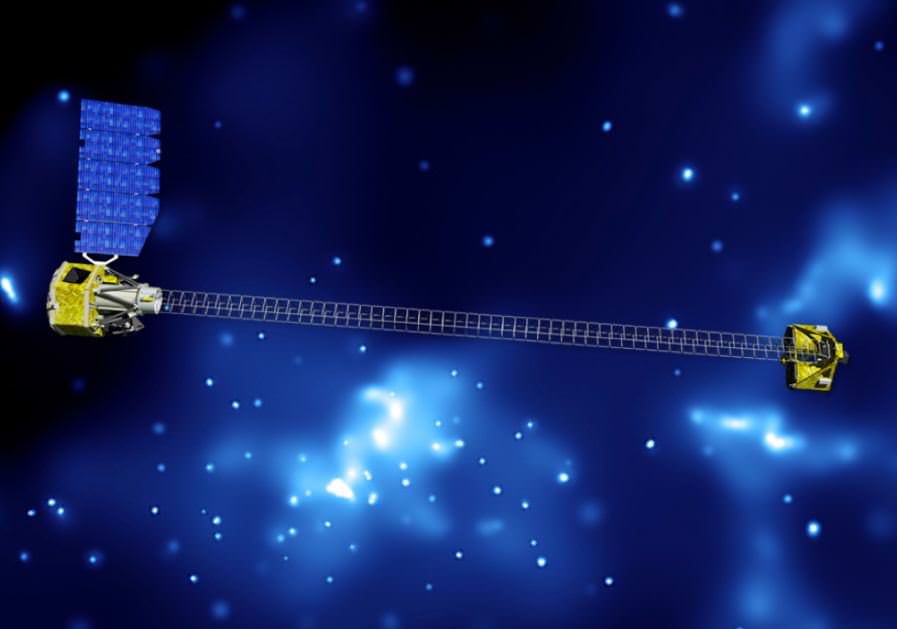

Now, thanks to NASA’s NuSTAR mission, we have our first solid clues to what happens before a star goes “boom.”

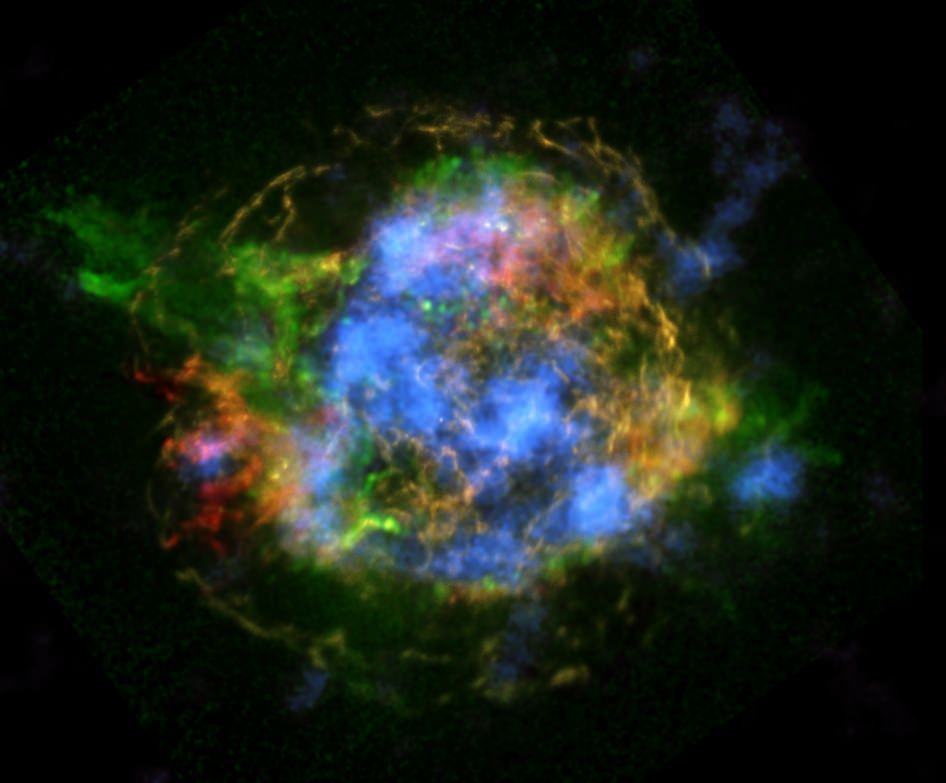

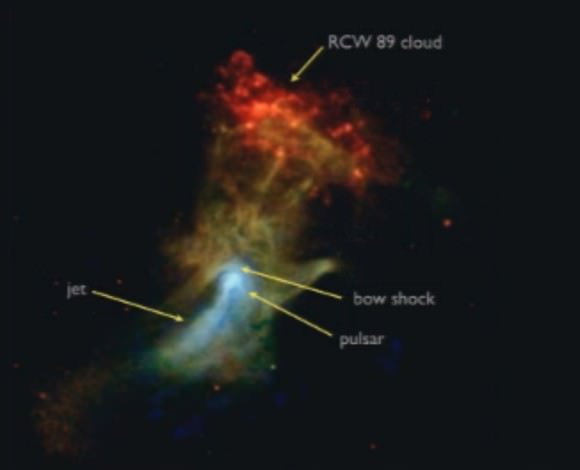

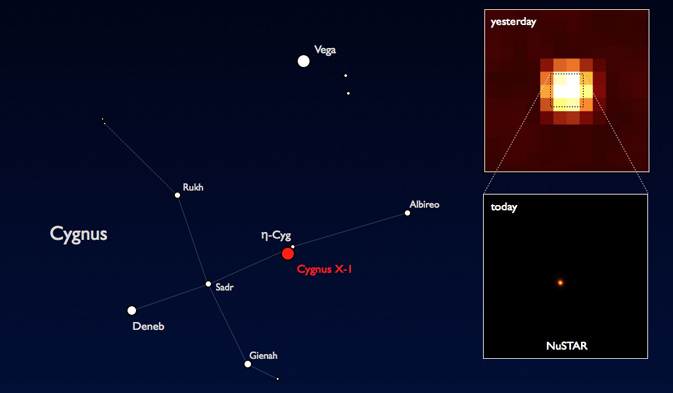

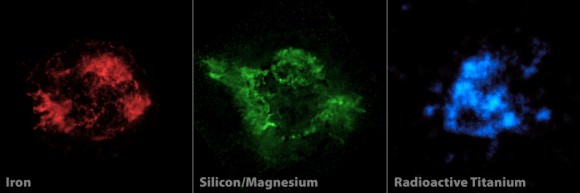

The image above shows the supernova remnant Cassiopeia A (or Cas A for short) with NuSTAR data in blue and observations from the Chandra X-ray Observatory in red, green, and yellow. It’s the shockwave left over from the explosion of a star about 15 to 25 times more massive than our Sun over 330 years ago*, and it glows in various wavelengths of light depending on the temperatures and types of elements present.

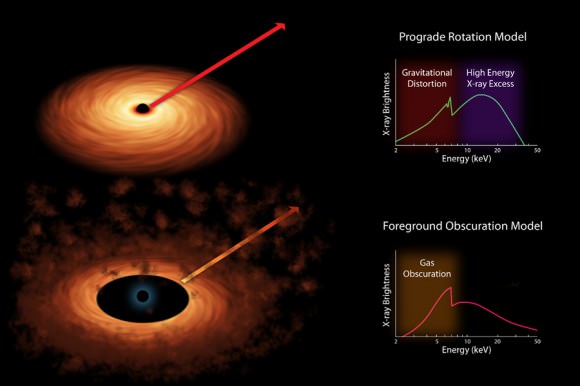

Previous observations with Chandra revealed x-ray emissions from expanding shells and filaments of hot iron-rich gas in Cas A, but they couldn’t peer deep enough to get a better idea of what’s inside the structure. It wasn’t until NASA’s Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array — that’s NuSTAR to those in the know — turned its x-ray vision on Cas A that the missing puzzle pieces could be found.

And they’re made of radioactive titanium.

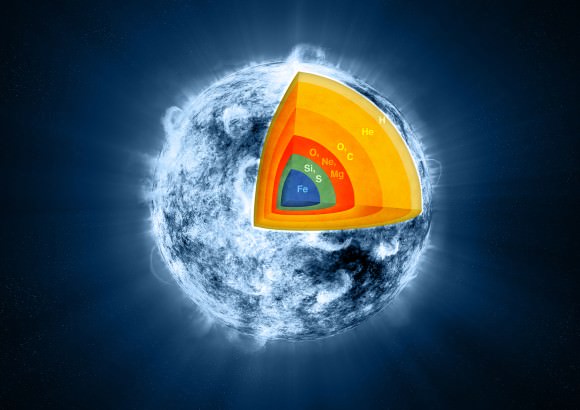

Many models have been made (using millions of hours of supercomputer time) to try to explain core-collapse supernovas. One of the leading ones has the star ripped apart by powerful jets firing from its poles — something that’s associated with even more powerful (but focused) gamma-ray bursts. But it didn’t appear that jets were the cause with Cas A, which doesn’t exhibit elemental remains within its jet structures… and besides, the models relying on jets alone didn’t always result in a full-blown supernova.

As it turns out, the presence of asymmetric clumps of radioactive titanium deep within the shells of Cas A, revealed in high-energy x-rays by NuSTAR, point to a surprisingly different process at play: a “sloshing” of material within the progenitor star that kickstarts a shockwave, ultimately tearing it apart.

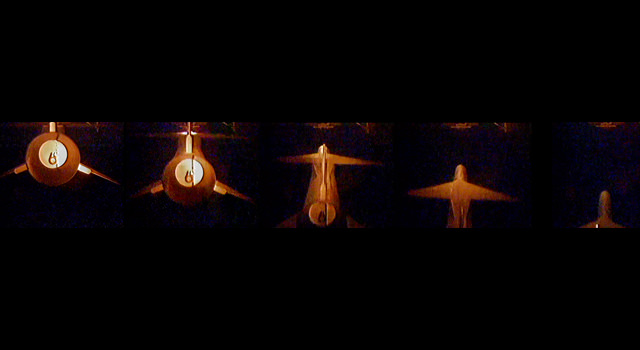

Watch an animation of how this process occurs:

The sloshing, which occurs over a time span of a mere couple hundred milliseconds — literally in the blink of an eye — is likened to boiling water on a stove. When the bubbles break through the surface, the steam erupts.

Only in this case the eruption leads to the insanely powerful detonation of an entire star, blasting a shockwave of high-energy particles into the interstellar medium and scattering a periodic tableful of heavy elements into the galaxy.

In the case of Cas A, titanium-44 was ejected, in clumps that echo the shape of the original sloshing asymmetry. NuSTAR was able to image and map the titanium, which glows in x-ray because of its radioactivity (and not because it’s heated by expanding shockwaves, like other lighter elements visible to Chandra.)

“Until we had NuSTAR we couldn’t really see down into the core of the explosion,” said Caltech astronomer Brian Grefenstette during a NASA teleconference on Feb. 19.

“Previously, it was hard to interpret what was going on in Cas A because the material that we could see only glows in X-rays when it’s heated up. Now that we can see the radioactive material, which glows in X-rays no matter what, we are getting a more complete picture of what was going on at the core of the explosion.”

– Brian Grefenstette, lead author, Caltech

Okay, so great, you say. NASA’s NuSTAR has found the glow of titanium in the leftovers of a blown-up star, Chandra saw some iron, and we know it sloshed and ‘boiled’ a fraction of a second before it exploded. So what?

“Now you should care about this,” said astronomer Robert Kirshner of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. “Supernovae make the chemical elements, so if you bought an American car, it wasn’t made in Detroit two years ago; the iron atoms in that steel were manufactured in an ancient supernova explosion that took place five billion years ago. And NuSTAR shows that the titanium that’s in your Uncle Jack’s replacement hip were made in that explosion too.

“We’re all stardust, and NuSTAR is showing us where we came from. Including our replacement parts. So you should care about this… and so should your Uncle Jack.”

And it’s not just core-collapse supernovas that NuSTAR will be able to investigate. Other types of supernovas will be scrutinized too — in the case of SN2014J, a Type Ia that was spotted in M82 in January, even right after they occur.

“We know that those are a type of white dwarf star that detonates,” NuSTAR principal investigator Fiona Harrison responded to Universe Today during the teleconference. “This is very exciting news… NuSTAR has been looking at [SN2014J] for weeks, and we hope to be able to say something about that explosion as well.”

One of the most valuable achievements of the recent NuSTAR findings is having a new set of observed constraints to place on future models of core-collapse supernovas… which will help provide answers — and likely new questions — about how stars explode, even hundreds or thousands of years after they do.

“NuSTAR is pioneering science, and you have to expect that when you get new results, it’ll open up as many questions as you answer,” said Kirshner.

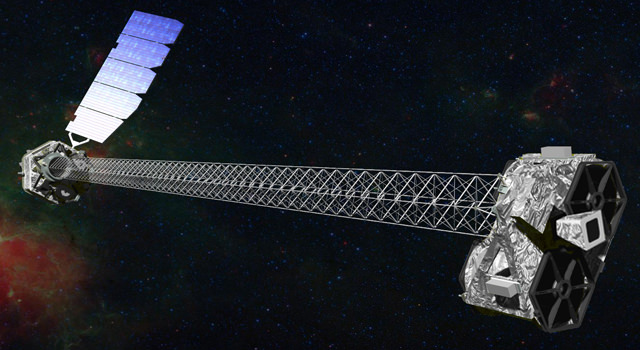

Launched in June of 2012, NuSTAR is the first focusing hard X-ray telescope to orbit Earth and the first telescope capable of producing maps of radioactive elements in supernova remnants.

Read more on the JPL news release here, and listen to the full press conference here.

*As Cas A resides 11,000 light-years from Earth, the actual date of the supernova would be about 11,330 years ago. Give or take a few.