Quick… what’s the only major meteor shower named after a defunct constellation? If you said the January Quadrantids, you’d be correct, as this often elusive but abrupt meteor shower is set to peak this coming weekend early in 2015.

And we do mean early, as in the night of January 3rd going into the morning of January 4th. This is a bonus, as early January means long dark nights for northern hemisphere observers. But the 2015 Quadrantids also has two strikes going against them however: first, the Moon reaches Full just a day later on January 5th, and second, January also means higher than average prospects for cloud cover (and of course, frigid temps!) for North American observers.

Don’t despair, however. In meteor shower observing as in hockey, you miss 100% of the shots that you don’t take.

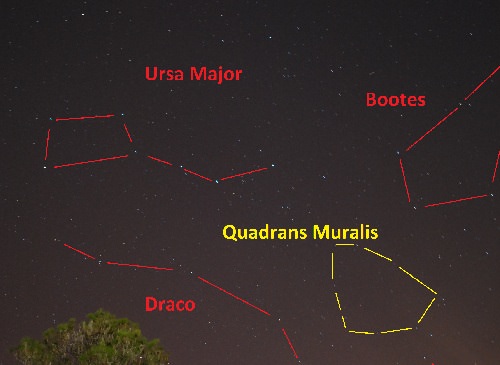

Sorry for the sports analogy. The radiant for the Quadrantids is located in the modern day constellation of Draco near the Hercules-Boötes border at a right ascension 15 hours, 18 minutes and declination +49.5 degrees north. This puts it very near the +3.3 magnitude star Iota Draconis (Edasich).

In 2015, bets are on for the Quadrantids to peak centered on 2:00 UT January 4th (9:00 PM EST on the 3rd), favoring northern Europe pre-dawn. The duration for the Quadrantids is short lived, with an elevated rate approaching 100 per hour lasting only six hours in duration. Keep in mind, of course, that it’ll be worth starting your vigil on Saturday morning January 3rd in the event that the “Quads” kick off early! I definitely wouldn’t pass up on an early clear morning on the 3rd, just in case skies are overcast on the morning of the 4th…

Due to their high northern radiant, the Quadrantids are best from high northern latitudes and virtually invisible down south of the equator. Keep in mind that several other meteor showers are active in early January, and you may just spy a lingering late season Geminid or Ursid ‘photobomber’ as well among the background sporadics.

Moonset on the morning of the 4th occurs around 6 AM local, giving observers a slim one hour moonless window as dawn approaches. Blocking the Moon out behind a building or hill when selecting your observing site will aid you in your Quadrantid quest.

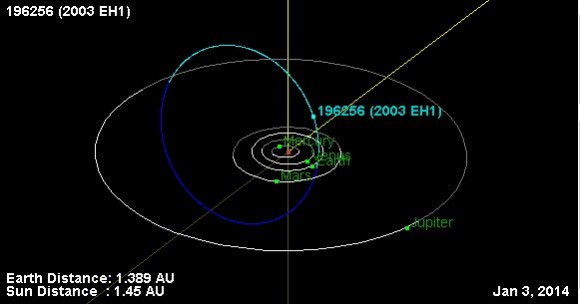

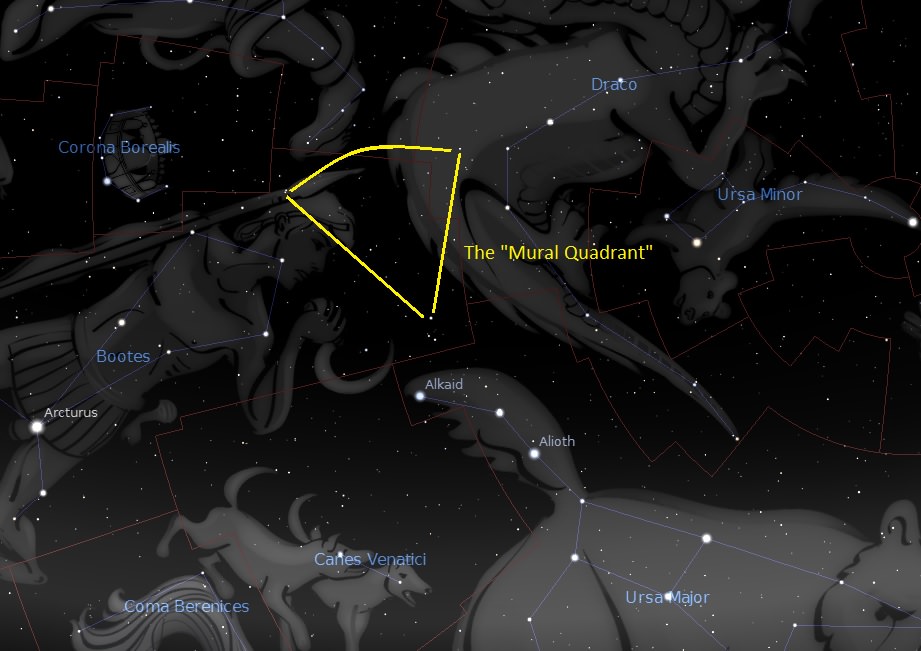

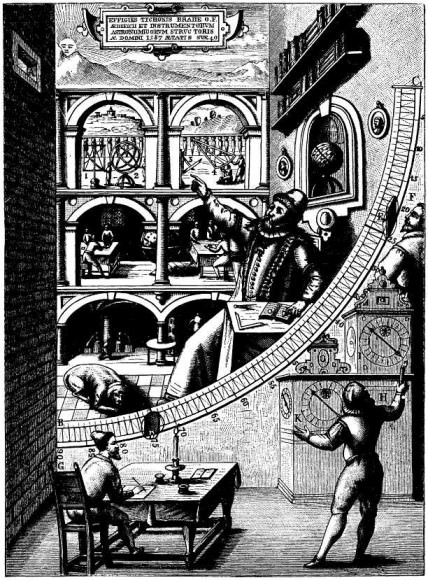

Antonio Brucalassi made the first historical reference to the Quadrantids, noting that “the atmosphere was traversed by… falling stars” on the morning of January 2nd, 1825. It’s interesting to note that the modern day peak for the Quads has now drifted a few days to the fourth, due mostly to the leap year-induced vagaries of our Gregorian calendar. The early January meteor shower was noted throughout the 19th century, and managed to grab its name from the trendy 19th century constellation of Quadrans Muralis, or the Mural Quadrant. Hey, we’re lucky that other also-rans, such as Lumbricus the ‘Earthworm’ and Officina Typograhica the ‘Printing Office’ fell to the wayside when the International Astronomical Union formalized the modern 88 constellations in 1922. Today, we know that the Quadrantids come from 2003 EH1, which is thought to be an extinct comet now trapped in the inner solar system on a high inclination, 5.5 year orbit. Could 2003 EH1 be related to the Great Comet of 1490, as some suggest? The enigmatic object reached perihelion in March of 2014, another plus in the positive column for the 2015 Quads.

Previous years for the Quadrantids have yielded the following Zenithal Hourly Rate (ZHR) maximums as per the International Meteor Organization:

2011= 90

2012= 83

2013= 137

2014= +200

The Quadrantid meteor stream has certainly undergone alterations over the years as a result of encounters with the planet Jupiter, and researchers have suggested that the shower may go the way of the 19th century Andromedids and become extinct entirely in the centuries to come.

Don’t let cold weather deter you, though be sure to bundle up, pour a hot toddy (or tea or coffee, as alcohol impacts the night vision) and keep a spare set of batteries in a warm pocket for that DSLR camera, as cold temps can kill battery packs quicker than you can say Custos Messium, the Harvest Keeper.

And though it may be teeth-chatteringly cold where you live this weekend, we actually reach our closest point to the Sun this Sunday, as Earth reaches perihelion on January 4th at around 8:00 UT, just 5 hours after the Quads are expected to peak. We’re just over 147 million kilometres from the Sun at perihelion, a 5 million kilometre difference from aphelion in July. Be thankful we live on a planet with a relatively circular orbit. Only Venus and Neptune beat us out in the true roundness department!

…and no, you CAN’T defy gravity around perihelion, despite the current ill conceived rumor going ‘round ye ole net…

And as a consolation prize to southern hemisphere observers, the International Space Station reaches a period of full illumination and makes multiple visible passes starting December 30th until January 3rd. This happens near every solstice, with the December season favoring the southern hemisphere, and June favoring the northern.

So don’t let the relatively bad prospects for the 2015 Quadrantids deter you: be vigilant, report those meteor counts to the IMO, send those meteor pics in to Universe Today and tweet those Quads to #Meteorwatch. Let’s “party like it’s 1899,” and get the namesake of an archaic and antiquated constellation trending!