The wonderful thing about science is that it’s constantly searching for new evidence, revising estimates, throwing out theories, and sometimes discovering aspects of the Universe that we never realized existed.

The best science is skeptical of itself, always examining its own theories to find out where they could be wrong, and seriously considering new ideas to see if they better explain the observations and data.

What this means is that whenever I state some conclusion that science has reached, you can’t come back a few years later and throw that answer in my face. Science changes, it’s not my fault.

I get it, VY Canis Majoris isn’t the biggest star any more, it’s whatever the biggest star is right now. UY Scuti? That what it is today, but I’m sure it’ll be a totally different star when you watch this in a few years.

What I’m saying is, the science changes, numbers update, and we don’t need to get concerned when it happens. Change is a good thing. And so, it’s with no big surprise that I need to update the estimate for the number of galaxies in the observable Universe. Until a couple of weeks ago, the established count for galaxies was about 200 billion galaxies.

But a new paper published in the Astrophysics Journal revised the estimate for the number of galaxies, by a factor of 10, from 200 billion to 2 trillion. 200 billion, I could wrap my head around, I say billion all the time. But 2 trillion? That’s just an incomprehensible number.

Does that throw all the previous estimates for the number of stars up as well? Actually, it doesn’t.

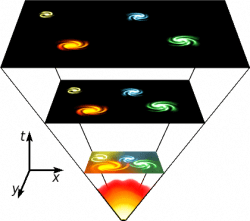

The observable Universe measures 13.8 billion light-years in all directions. What this means is that at the very edge of what we can see, is the light left that region 13.8 billion years ago. Furthermore, the expansion of the Universe has carried to those regions 46 billion light-years away.

Does that make sense? The light you’re seeing is 13.8 billion light-years old, but now it’s 46 billion light-years away. What this means is that the expansion of space has stretched out the light from all the photons trying to reach us.

What might have been visible or ultraviolet radiation in the past, has shifted into infrared, and even microwaves at the very edge of the observable Universe.

Since astronomers know the volume of the observable Universe, and they can calculate the density of the Universe, they know the mass of the entire Universe. 3.4 x 10^54 kilograms including regular matter and dark matter. They also know the ratio of regular matter to dark matter, so they can calculate the total amount of regular mass in the Universe.

In the past, astronomers divided that total mass by the number of galaxies they could see in the original Hubble data and determined there were about 200 billion galaxies.

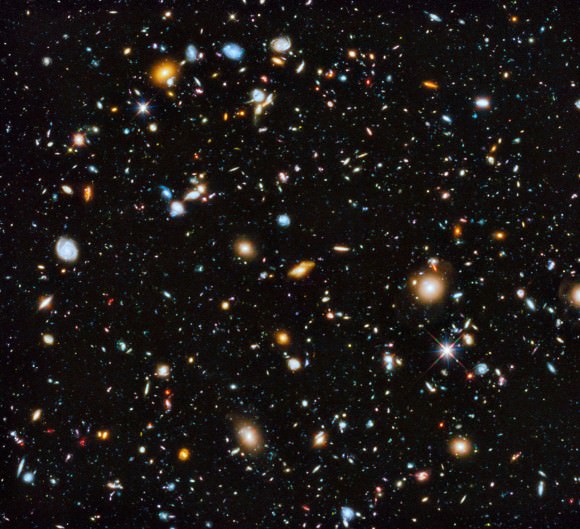

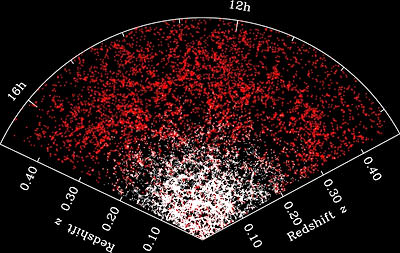

Now, astronomers used a new technique to estimate the galaxies and it’s pretty cool. Astronomers used the Hubble Space Telescope to peer into a seemingly empty part of the sky and identified all the galaxies in it. This is the Hubble Ultra Deep Field, and it’s one of the most amazing pictures Hubble has ever captured.

Astronomers painstakingly converted this image of galaxies into a 3-dimensional map of galaxy size and locations. Then, they used their knowledge of galaxy structure closer to home to provide a more accurate estimate of what the galaxies must look like, out there, at the very edge of our observational ability.

For example, the Milky Way is surrounded by about 50 satellite dwarf galaxies, each of which has a fraction of the mass of the Milky Way.

By recognizing which were the larger main galaxies, they could calculate the distribution of smaller, dimmer dwarf galaxies that weren’t visible in the Hubble images.

In other words, if the distant Universe is similar to the nearby Universe, and this is one of the principles of modern astronomy, then the distant galaxies have the same structure as nearby galaxies.

It doesn’t mean that the Universe is bigger than we thought, or that there are more stars, it just means that the Universe contains more galaxies, which have less stars in them. There are the big main galaxies, and then a smooth distribution curve of smaller and smaller galaxies down to the tiny dwarf galaxies. The total number of stars comes out to be the same number.

The galaxies we can see are just the tip of the galactic iceberg. For every galaxy we can see, there are another 9, smaller fainter galaxies that we can’t see.

Of course, we’re just a few years away from being able to see these dimmer galaxies. When NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope launches in October, 2018, it’s going to be carrying a telescope mirror with 25 square meters of collecting surface, compared to Hubble’s 4.5 square meters.

Furthermore, James Webb is an infrared telescope, a specialized tool for looking at cooler objects, and galaxies which are billions of light-years away. The kinds of galaxies that Hubble can only hint at, James Webb will be able to see directly.

So, why don’t we see galaxies in all directions with our eyeballs? This is actually an old conundrum, proposed by Wilhelm Olbers in the 1700, appropriately named Olber’s Paradox. We did a whole article on it, but the basic idea is that if you look in any direction, you’ll eventually hit a star. It could be close, like the Sun, or very far away, but whatever the case, it should be stars in all directions. Which means that the entire night sky should be as bright as the surface of a star. Clearly it isn’t, but why isn’t it?

In fact, with 10 times the number of galaxies, you could restate the paradox and say that in every direction, you should be looking at a galaxy, but that’s not what you see.

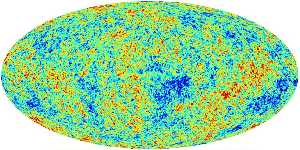

Except you are. Everywhere you look, in all directions, you’re seeing galaxies. It’s just that those galaxies are red-shifted from the visible spectrum into the infrared spectrum, so your eyeballs can’t perceive them. But they’re there.

When you see the sky in microwaves, it does indeed glow in all directions. That’s the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation, shining behind all those galaxies.

It turns out the Universe has 10 times more galaxies than previously estimated – 2 trillion galaxies. Not 10 times the stars or mass, those numbers have stayed the same.

And, once James Webb launches, those numbers will be fine-tuned again to be even more precise. 1.5 trillion? 3.4 trillion? Stay tuned for the better number.