As completion nears for the prototype of Boeing’s first Starliner astronaut taxi, the aerospace firm announced a slip into 2018 for the blastoff date of the first crewed flight in order to deal with spacecraft mass, aerodynamic launch and flight software issues, a Boeing spokesperson told Universe Today.

Until this week, Boeing was aiming for a first crewed launch of the commercial Starliner capsule by late 2017, company officials had said.

The new target launch date for the first astronauts flying aboard a Boeing CST-100 Starliner “is February 2018,” Boeing spokeswoman Rebecca Regan told Universe Today.

“Until very recently we were marching toward the 2017 target date.”

Word of the launch postponement came on Wednesday via an announcement by Boeing executive vice president Leanne Caret at a company investor conference.

Boeing will conduct two critical unmanned test flights leading up to the manned test flight and has notified NASA of the revised flight schedule.

“The Pad Abort test is October 2017 in New Mexico. Boeing will fly an uncrewed orbital flight test in December 2017 and a crewed orbital flight test in February 2018,” Regan told me.

Previously, the uncrewed and crewed test flights were slated for June and October 2017.

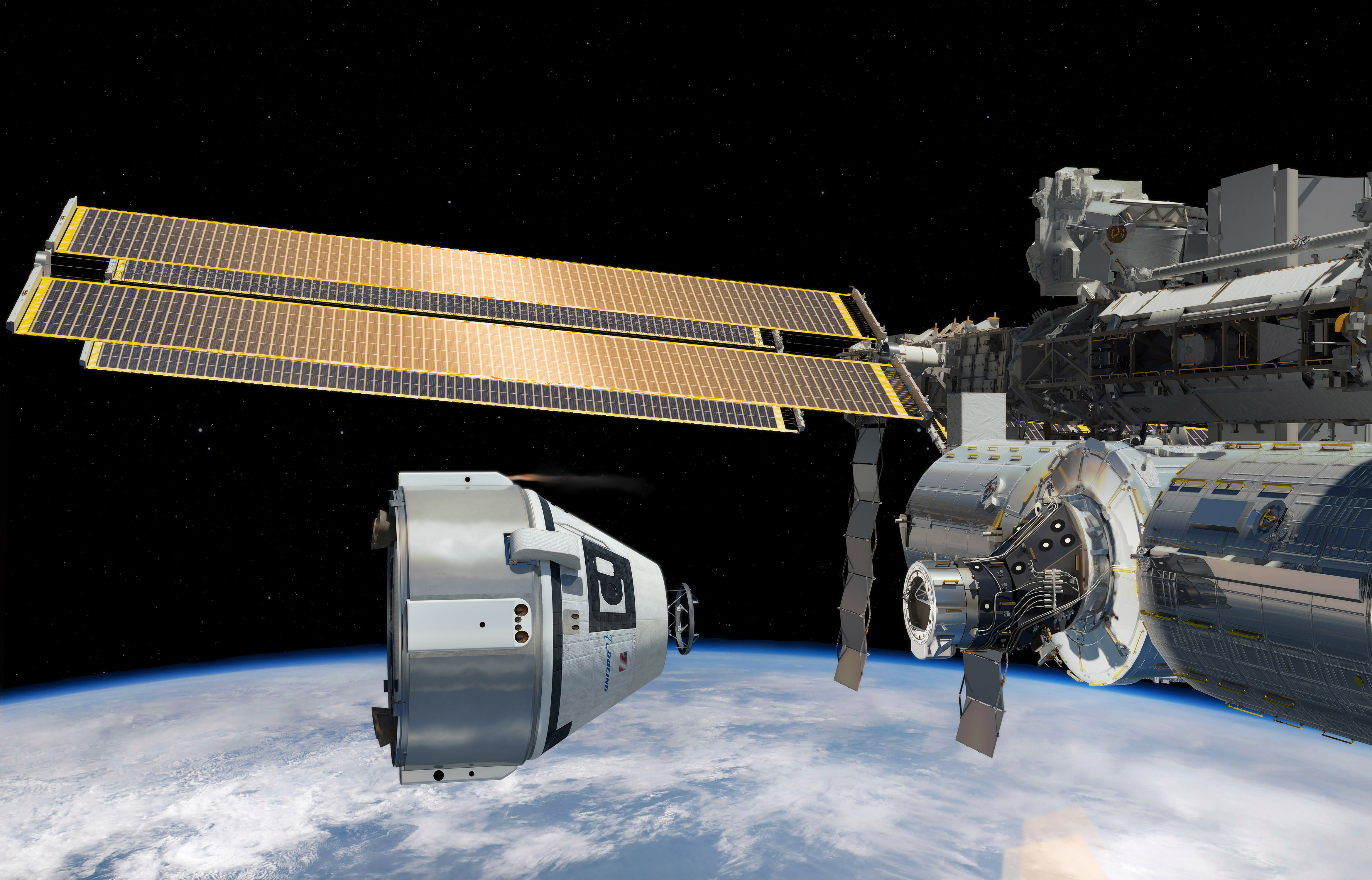

The inaugural crew flight will carry two astronauts to the International Space Station including a Boeing test pilot and a NASA astronaut.

“Boeing just recently presented this new schedule to NASA that gives a realistic look at where we are in the development. These programs are challenging.”

“As we build and test we are learning things. We are doing everything we can to make sure the vehicle is ready and safe – because that’s what most important,” Regan emphasized.

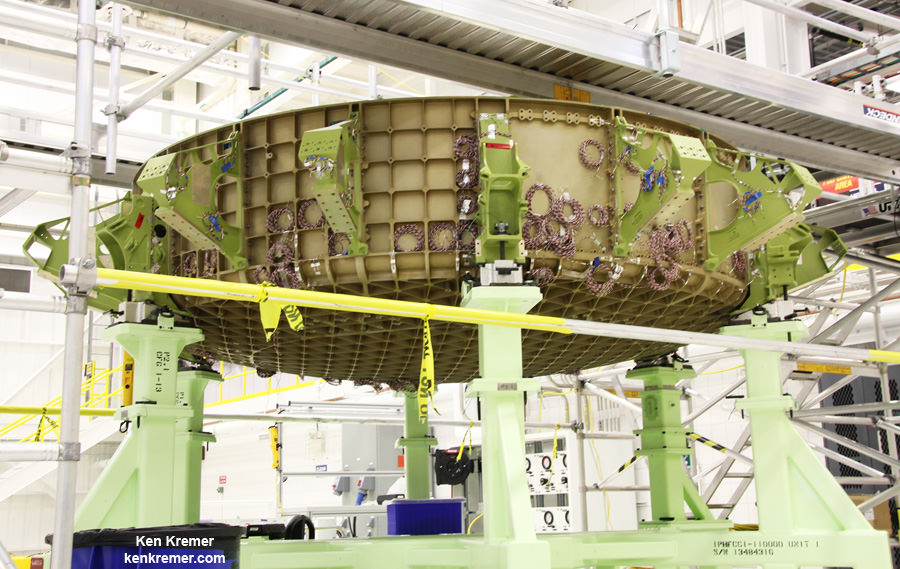

Indeed engineers just bolted together the upper and lower domes of Boeings maiden Starliner crew module last week, on May 2, forming the complete hull of the pressure vessel for the Structural Test Article (STA).

Altogether there are 216 holes for the bolts. They have to line up perfectly. The seals are checked to make sure there are no leaks, which could be deadly in space.

Starliner is being manufactured in Boeing’s Commercial Crew and Cargo Processing Facility (C3PF) at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida.

The STA will be subjected to rigorous environmental and loads testing to prove its fitness to fly humans to space and survive the harsh extremes of the space environment.

Regan cited three technical factors accounting for the delayed launch schedule. The first relates to mass.

“There are a couple of things that impacted the schedule as discussed recently by John Elbon, Boeing vice president and general manager of Space Exploration.”

“First is mass of the spacecraft. Mass whether it’s from aircraft or spacecraft is obviously always something that’s inside the box. We are working that,” Regan stated.

The second relates to aerodynamic loads which Boeing engineers believe they may have solved.

“Another challenge is aero-acoustic issues related to the spacecraft atop the launch vehicle. Data showed us that the spacecraft was experiencing some pressures [during launch] that we needed to go work on more.”

Starliners will launch to space atop the United Launch Alliance (ULA) Atlas V rocket from pad 41 on Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida.

“The aerodynamic acoustic loads data we were getting told us that we needed to go do some additional work. We actually now have a really viable option that we are testing right now in a wind tunnel this month.”

“So we think we are on the right path there. We have some design options we are looking at. We think we found a viable option that’s inside the scope of where we need to be on those aerodynamic acoustics in load.”

“So we will look at the data from the new wind tunnel tests.”

The third relates to new software requirements from NASA for docking at the ISS.

“NASA also levied some additional software requirements on us, in order to dock with the station. So those additional software requirements alone, in the contract, probably added about 3 months to our schedule, for our developers to work that.”

The Boeing CST 100 Starliner is one of two private astronaut capsules – along with the SpaceX Crew Dragon – being developed under a commercial partnership contract with NASA to end our sole reliance on Russia for crew launches back and forth to the International Space Station (ISS).

The goal of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program (CCP) is to restore America’s capability to launch American astronauts on American rockets from American soil to the ISS, as soon as possible.

Boeing was awarded a $4.2 Billion contract in September 2014 by NASA Administrator Charles Bolden to complete development and manufacture of the CST-100 Starliner space taxi under the agency’s Commercial Crew Transportation Capability (CCtCap) program and NASA’s Launch America initiative.

Since the retirement of NASA’s space shuttle program in 2011, the US was been 100% dependent on the Russian Soyuz capsule for astronauts rides to the ISS at a cost exceeding $70 million per seat.

Due to huge CCP funding cuts by Congress, the targeted launch dates for both Starliner and Crew Dragon have been delayed repeatedly from the initially planned 2015 timeframe to the latest goal of 2017.

The Structural Test Article plays a critical role serving as the pathfinder vehicle to validate the manufacturing and processing methods for the production of all the operational spacecraft that will follow in the future.

Although it will never fly in space, the STA is currently being built inside the renovated C3PF using the same techniques and processes planned for the operational spacecraft that will carry astronaut crews of four or more aloft to the ISS in 2018 and beyond.

“The Structural Test Article is not meant to ever fly in space but rather to prove the manufacturing methods and overall ability of the spacecraft to handle the demands of spaceflight carrying astronauts to the International Space Station,” says NASA.

The STA is also the first spacecraft to come together inside the former shuttle hangar known as an orbiter processing facility, since shuttle Discovery was moved out of the facility following its retirement and move to the Smithsonian’s Udvar-Hazy Center near Washington, D.C., in 2012.

“It’s actually bustling in there right now, which is awesome. Really exciting stuff,”Regan told me.

Regan also confirmed that the completed Starliner STA will soon be transported to Boeing’s facility in Huntington Beach, California for a period of critical stress testing that verifies the capabilities and worthiness of the spacecraft.

“Boeing’s testing facility in Huntington Beach, California has all the facilities to do the structural testing and apply loads. They are set up to test spacecraft,” said Danom Buck, manager of Boeing’s Manufacturing and Engineering team at KSC, during a prior interview in the C3PF.

“At Huntington Beach we will test for all of the load cases that the vehicle will fly in and land in – so all of the worst stressing cases.”

“So we have predicted loads and will compare that to what we actually see in testing and see whether that matches what we predicted.”

NASA notes that “the tests must bear out that the capsules can handle the conditions of space as well as engine firings and the pressure of launch, ascent and reentry. In simple terms, it will be shaked, baked and tested to the extreme.”

Lessons learned will be applied to the first flight test models of the Starliner. Some of those parts have already arrived at KSC and are “in the manufacturing flow in Florida.”

“Our team is initiating qualification testing on dozens of components and preparing to assemble flight hardware,” said John Mulholland, vice president and program manager of Boeing’s Commercial Programs, in a statement. “These are the first steps in an incredibly exciting, important and challenging year.”

SpaceX has announced plans to launch their first crew Dragon test flight before the end of 2017.

But the launch schedules for both Boeing and SpaceX are subject to review, dependent on satisfactorily achieving all agreed to milestones under the CCP contracts and approval by NASA, and can change at any time. So additional schedule alternations are not unexpected.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and planetary science and human spaceflight news.