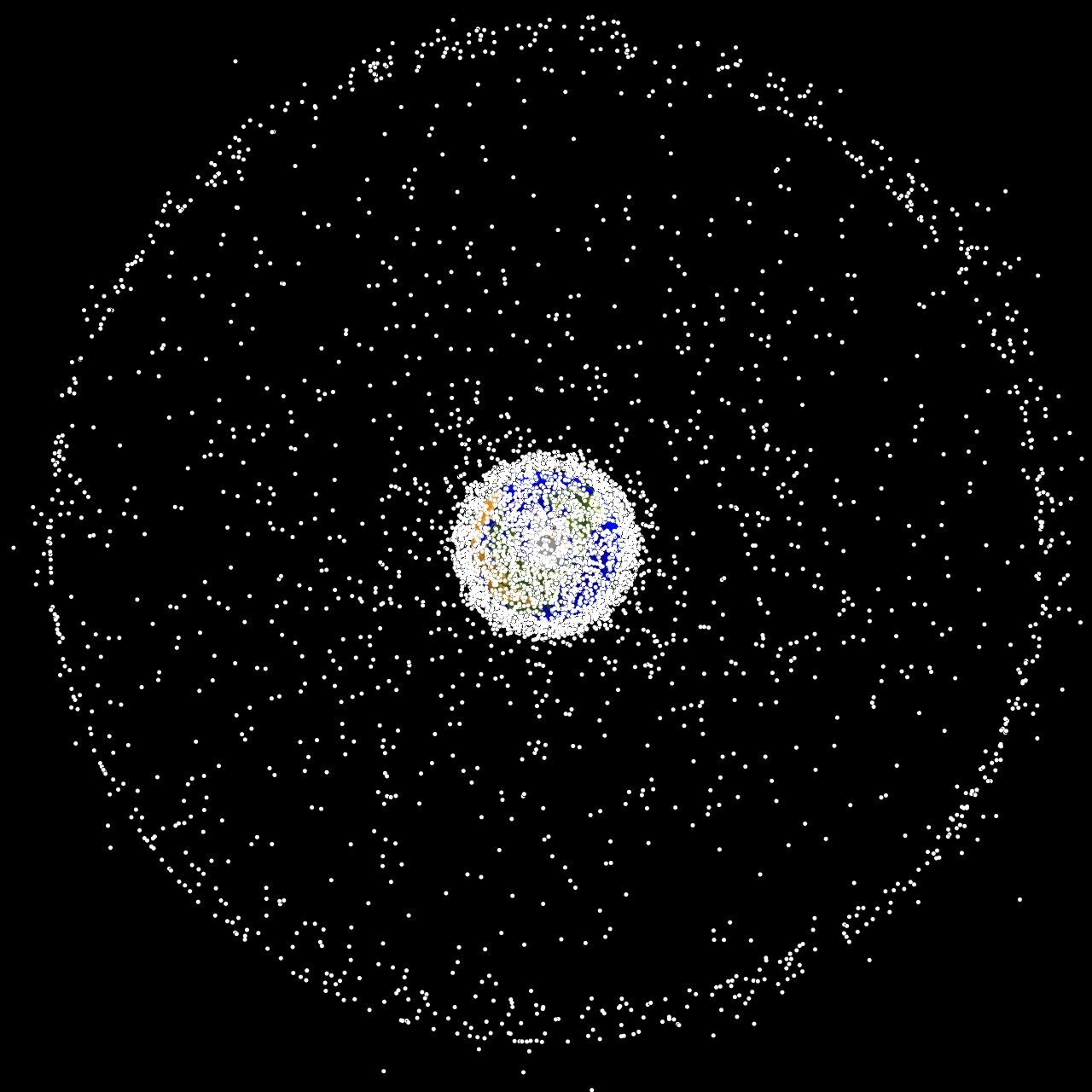

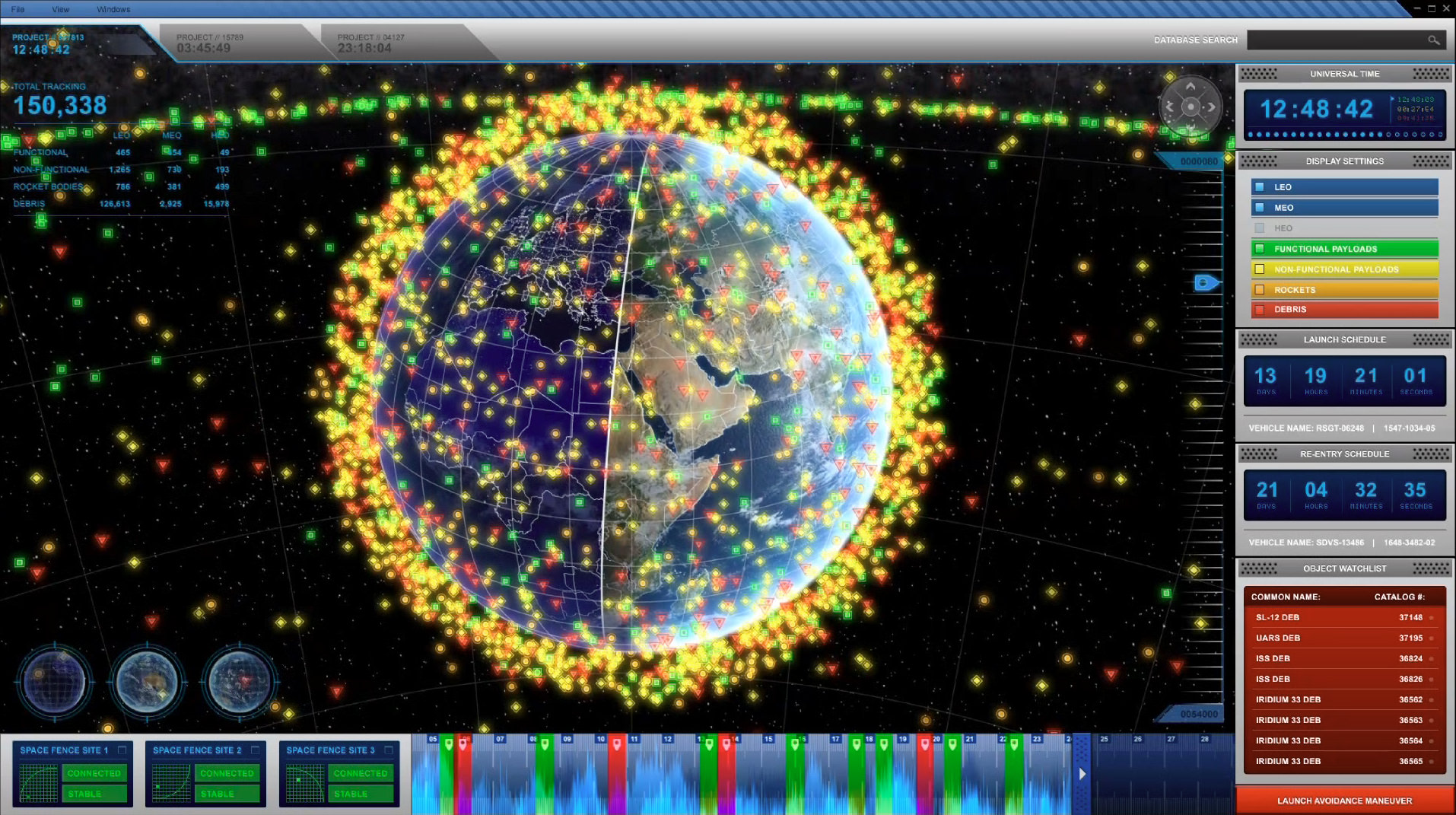

Since the 1960s, NASA and other space agencies have been sending more and more stuff into orbit. Between the spent stages of rockets, spent boosters, and satellites that have since become inactive, there’s been no shortage of artificial objects floating up there. Over time, this has created the significant (and growing) problem of space debris, which poses a serious threat to the International Space Station (ISS), active satellites and spacecraft.

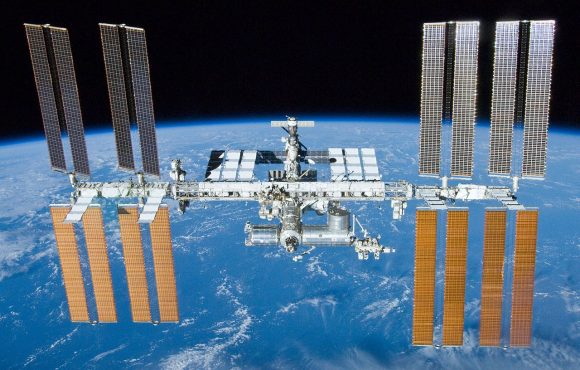

While the larger pieces of debris – ranging from 5 cm (2 inches) to 1 meter (1.09 yards) in diameter – are regularly monitored by NASA and other space agencies, the smaller pieces are undetectable. Combined with how common these small bits of debris are, this makes objects that measure about 1 millimeter in size a serious threat. To address this, the ISS is relying on a new instrument known as the Space Debris Sensor (SDS).

This calibrated impact sensor, which is mounted on the exterior of the station, monitors impacts caused by small-scale space debris. The sensor was incorporated into the ISS back in September, where it will monitor impacts for the next two to three years. This information will be used to measure and characterize the orbital debris environment and help space agencies develop additional counter-measures.

Measuring about 1 square meter (~10.76 ft²), the SDS is mounted on an external payload site which faces the velocity vector of the ISS. The sensor consists of a thin front layer of Kapton – a polyimide film that remains stable at extreme temperatures – followed by a second layer located 15 cm (5.9 inches) behind it. This second Kapton layer is equipped with acoustic sensors and a grid of resistive wires, followed by a sensored-embedded backstop.

This configuration allows the sensor to measure the size, speed, direction, time, and energy of any small debris it comes into contact with. While the acoustic sensors measure the time and location of a penetrating impact, the grid measures changes in resistance to provide size estimates of the impactor. The sensors in the backstop also measure the hole created by an impactor, which is used to determine the impactor’s velocity.

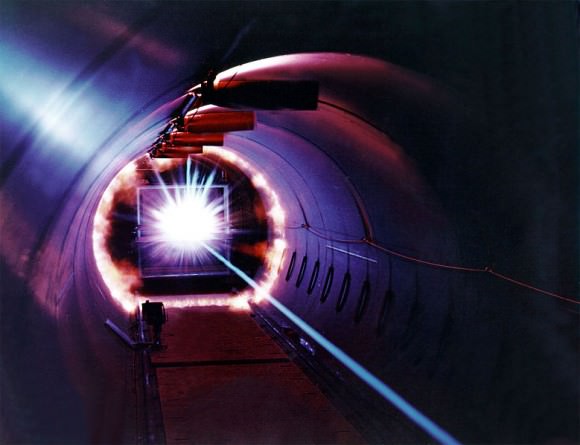

This data is then examined by scientists at the White Sands Test Facility in New Mexico and at the University of Kent in the UK, where hypervelocity tests are conducted under controlled conditions. As Dr. Mark Burchell, one of the co-investigators and collaborators on the SDS from the University of Kent, told Universe Today via email:

“The idea is a multi layer device. You get a time as you pass through each layer. By triangulating signals in a layer you get position in that layer. So two times and positions give a velocity… If you know the speed and direction you can get the orbit of the dust and that can tell you if it likely comes from deep space (natural dust) or is in a similar earth orbit to satellites so is likely debris. All this in real time as it is electronic.”

This data will improve safety aboard the ISS by allowing scientists to monitor the risks of collisions and generate more accurate estimates of how small-scale debris exists in space. As noted, the larger pieces of debris in orbit are monitored regularly. These consists of the roughly 20,000 objects that are about the size of a baseball, and an additional 50,000 that are about the size of a marble.

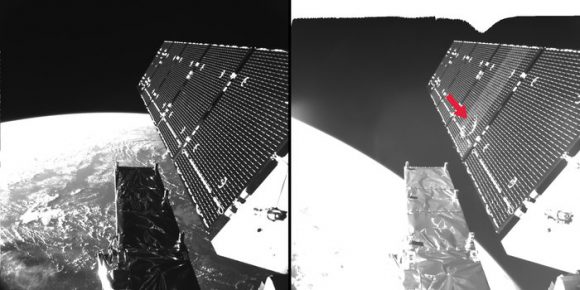

However, the SDS is focused on objects that are between 50 microns and 1 millimeter in diameter, which number in the millions. Though tiny, the fact that these objects move at speeds of over 28,000 km/h (17,500 mph) means that they can still cause significant damage to satellites and spacecraft. By being able to get a sense of these objects and how their population is changing in real-time, NASA will be able to determine if the problem of orbital debris is getting worse.

Knowing what the debris situation is like up there is also intrinsic to finding ways to mitigate it. This will not only come in handy when it comes to operations aoard the ISS, but in the coming years when the Space Launch System (SLS) and Orion capsule take to space. As Burchell added, knowing how likely collisions will be, and what kinds of damage they may cause, will help inform spacecraft design – particularly where shielding is concerned.

“[O]nce you know the hazard you can adjust the design of future missions to protect them from impacts, or you are more persuasive when telling satellite manufacturers they have to create less debris in future,” he said. “Or you know if you really need to get rid of old satellites/ junk before it breaks up and showers earth orbit with small mm scale debris.”

Dr. Jer Chyi Liou, in addition to being a co-investigator on the SDS, is also the NASA Chief Scientist for Orbital Debris and the Program Manager for the Orbital Debris Program Office at the Johnson Space Center. As he explained to Universe Today via email:

“The millimeter-sized orbital debris objects represent the highest penetration risk to the majority of operational spacecraft in low Earth orbit (LEO). The SDS mission will serve two purposes. First, the SDS will collect useful data on small debris at the ISS altitude. Second, the mission will demonstrate the capabilities of the SDS and enable NASA to seek mission opportunities to collect direct measurement data on millimeter-sized debris at higher LEO altitudes in the future – data that will be needed for reliable orbital debris impact risk assessments and cost-effective mitigation measures to better protect future space missions in LEO.”

The results from this experiment build upon previous information obtained by the Space Shuttle program. When the shuttles returned to Earth, teams of engineers inspected hardware that underwent collisions to determine the size and impact velocity of debris. The SDS is also validating the viability of impact sensor technology for future missions at higher altitudes, where risks from debris to spacecraft are greater than at the ISS altitude.

Further Reading: NASA