[/caption]

It was once thought that our planet was part of a “typical” solar system. Inner rocky worlds, outlying gas giants, some asteroids and comets sprinkled in for good measure. All rotating around a central star in more or less the same direction. Typical.

But after seeing what’s actually out there, it turns out ours may not be so typical after all…

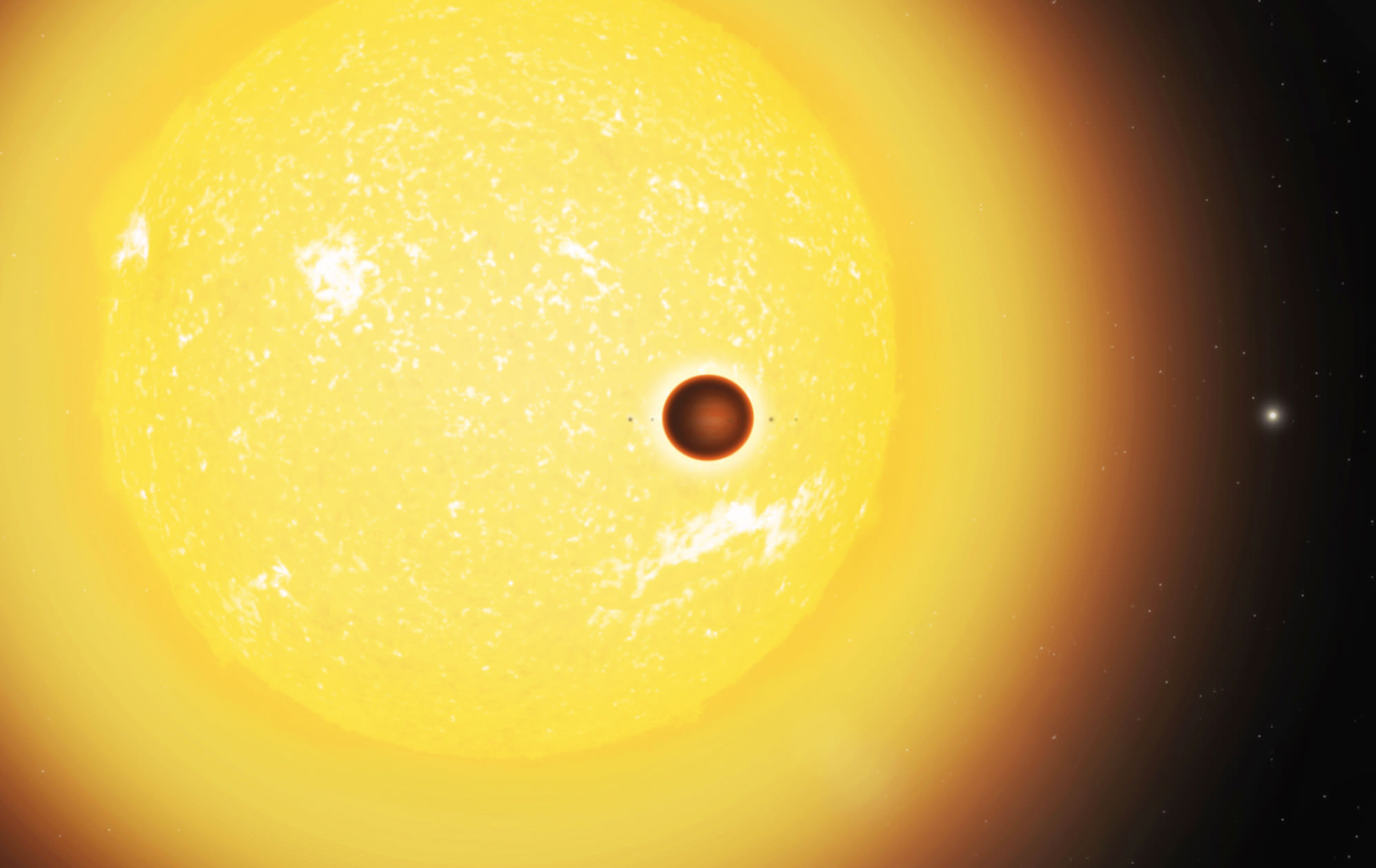

Astronomers researching exoplanetary systems – many discovered with NASA’s Kepler Observatory – have found quite a few containing “hot Jupiters” that orbit their parent star very closely. (A hot Jupiter is the term used for a gas giant – like Jupiter – that resides in an orbit very close to its star, is usually tidally locked, and thus gets very, very hot.) These worlds are like nothing seen in our own solar system…and it’s now known that some actually have retrograde orbits – that is, orbiting their star in the opposite direction.

“That’s really weird, and it’s even weirder because the planet is so close to the star. How can one be spinning one way and the other orbiting exactly the other way? It’s crazy. It so obviously violates our most basic picture of planet and star formation.”

– Frederic A. Rasio, theoretical astrophysicist, Northwestern University

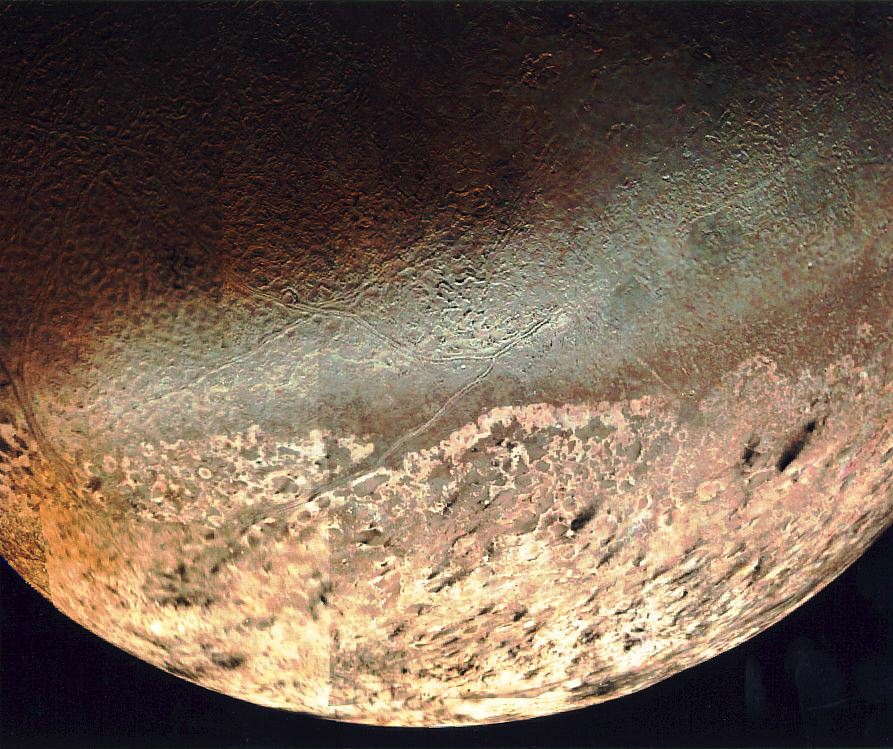

Now retrograde movement does exist in our solar system. Venus rotates in a retrograde direction, so the Sun rises in the west and sets in the east, and a few moons of the outer planets orbit “backwards” relative to the other moons. But none of the planets in our system have retrograde orbits; they all move around the Sun in the same direction that the Sun rotates. This is due to the principle of conservation of angular momentum, whereby the initial motion of the disk of gas that condensed to form our Sun and afterwards the planets is reflected in the current direction of orbital motions. Bottom line: the direction they moved when they were formed is (generally) the direction they move today, 4.6 billion years later. Newtonian physics is okay with this, and so are we. So why are we now finding planets that blatantly flaunt these rules?

The answer may be: peer pressure.

Or, more accurately, powerful tidal forces created by neighboring massive planets and the star itself.

By fine-tuning existing orbital mechanics calculations and creating computer simulations out of them, researchers have been able to show that large gas planets can be affected by a neighboring massive planet in such a way as to have their orbits drastically elongated, sending them spiraling closer in toward their star, making them very hot and, eventually, even flip them around. It’s just basic physics where energy is transferred between objects over time.

It just so happens that the objects in question are huge planets and the time scale is billions of years. Eventually something has to give. In this case it’s orbital direction.

“We had thought our solar system was typical in the universe, but from day one everything has looked weird in the extrasolar planetary systems. That makes us the oddball really. Learning about these other systems provides a context for how special our system is. We certainly seem to live in a special place.”

– Frederic A. Rasio

Yes, it certainly does seem that way.

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation. Details of the discovery are published in the May 12th issue of the journal Nature.

Read the press release here.

Main image credit: Jason Major. Created from SDO (AIA 304) image of the Sun from October 17, 2010 (NASA/SDO and the AIA science team) and an image of Jupiter taken by the Cassini-Huygens spacecraft on October 23, 2000 (NASA/JPL/SSI).