In a recent study submitted to the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society for the 8th Interstellar Symposium special issue, which is due for publication sometime in 2024, Dr. Jacob Haqq-Misra, who is a senior research investigator and the Chief Operating Officer and co-founder at the Blue Marble Space Institute of Science, examines how future space exploration governing laws could evolve, either crewed or uncrewed and in the solar system or beyond. He views this study as an expansion of interplanetary governance models he previously discussed in his book, Sovereign Mars, to explore potential limits on space governance at interstellar distances.

Continue reading “The Outer Space Treaty was Signed in 1967. Can it Handle the Future of Space Exploration?”Move Over Artemis Accords! Behold the Lunar Governance Report and EAGLE Manifesto!

In July 1999, the Space Generation Advisory Council (SGAC) was created with the purpose of representing the “Space Generation” to the UN Office of Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA). For this non-governmental organization and professional network, this would consist of bringing the “views of students and young space professionals to the United Nations (UN), space industry and other organizations”.

Given the importance of the Moon for all of our future space exploration goals, SGAC created an interdisciplinary group in June of 2020 that is focused on lunar policy. Known as the Effective and Adaptive Governance for a Lunar Ecosystem (E.A.G.L.E.), this group of 14 young space professionals is dedicated to ensuring that the younger generation has a voice when it comes to the development of regulations for lunar policy.

On May 12th, 2021, the SGAC released the report prepared by the EAGLE group, which outlines their ideas and proposals for how we can ensure that the regulations governing lunar activities are inclusive, effective, and adaptative. It’s known as the Lunar Governance Report, a document that will be presented during the 2021 meetings of the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS).

Continue reading “Move Over Artemis Accords! Behold the Lunar Governance Report and EAGLE Manifesto!”The Moon has Resources, but Not Enough to Go Around

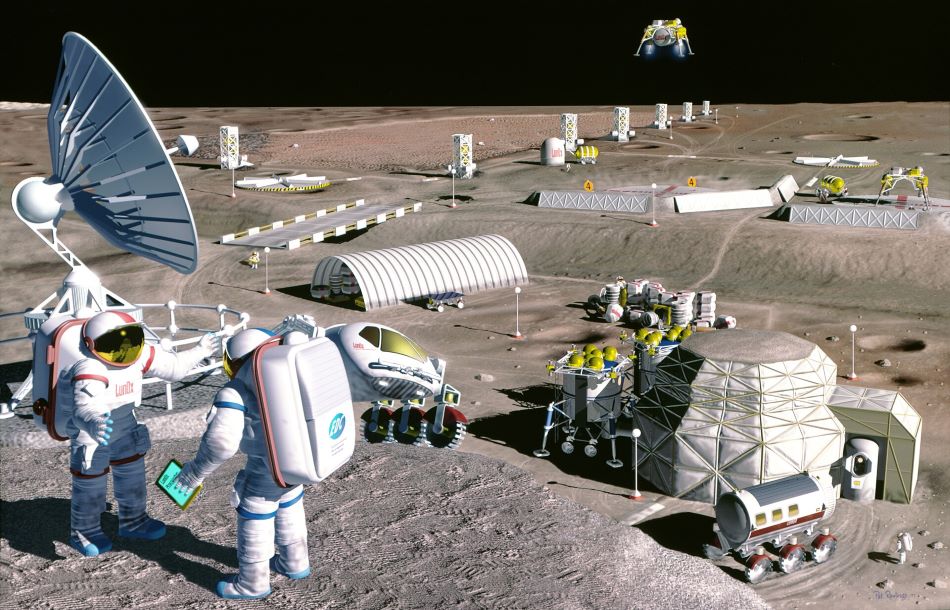

It’s no secret that in this decade, NASA and other space agencies will be taking us back to the Moon (to stay, this time!) The key to this plan is developing the necessary infrastructure to support a sustainable program of crewed exploration and research. The commercial space sector also hopes to create lunar tourism and lunar mining, extracting and selling some of the Moon’s vast resources on the open market.

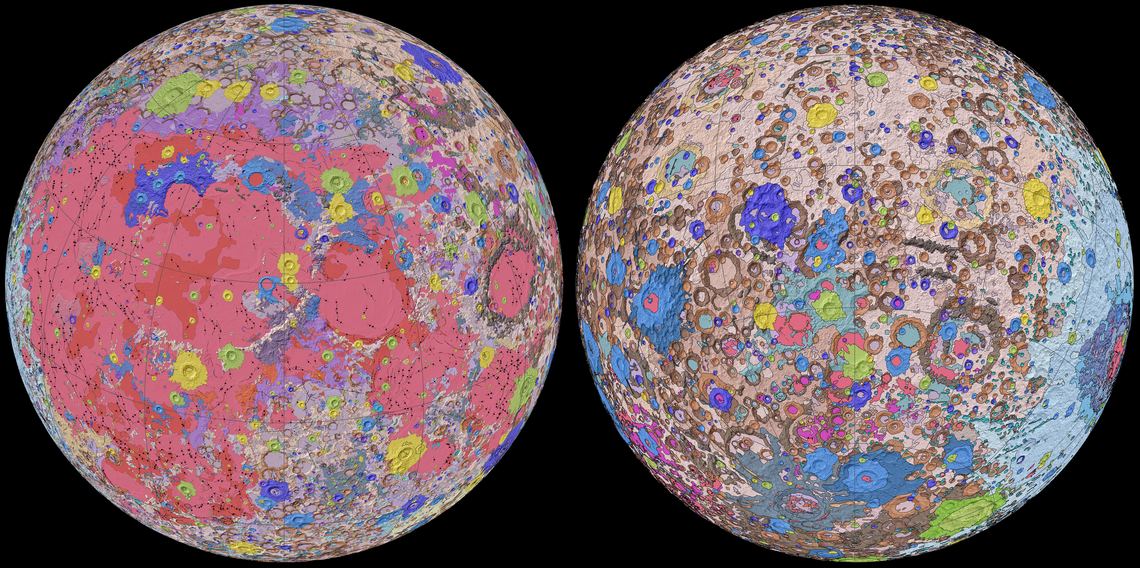

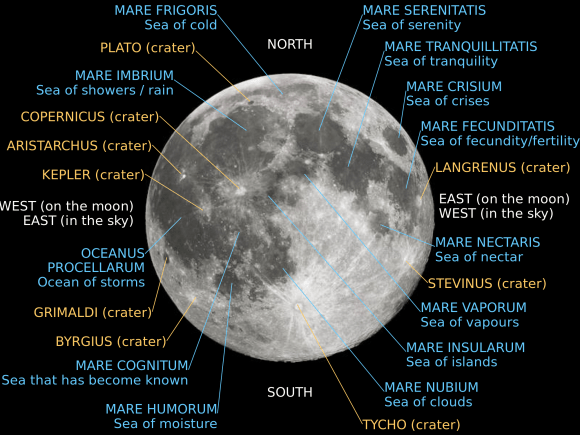

Ah, but there’s a snag! According to an international team of scientists led by the Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), there may not be enough resources on the Moon to go around. Without some clear international policies and agreements in place to determine who can claim what and where, the Moon could quickly become overcrowded, overburdened, and stripped of its resources.

Continue reading “The Moon has Resources, but Not Enough to Go Around”The Space Court Foundation is Now in Session!

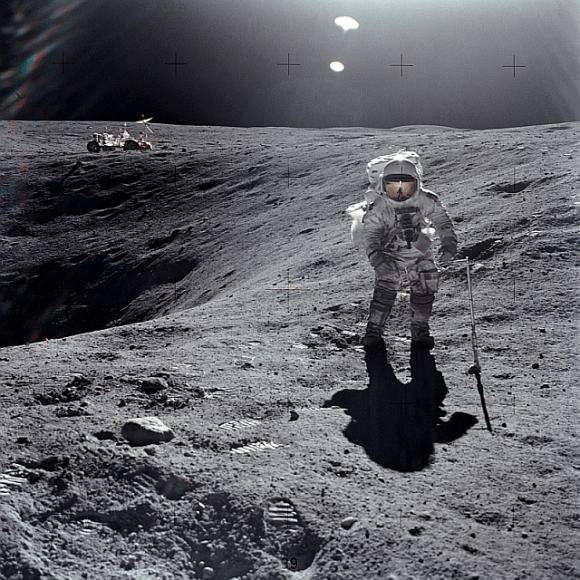

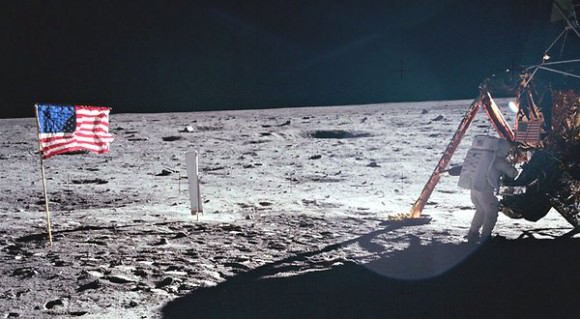

With the closing of the Apollo Era, the priorities of the world’s space agencies began to shift. Having spent the past two decades racing to send astronauts to orbit and to the Moon, the focus now changed towards developing the technologies needed to stay there. A new era of international cooperation, space stations, and partnerships between space agencies and the commercial industry is what followed.

In the near future, things are expected to become even more interesting, with plans for the commercialization of Low Earth Orbit (LEO), the mining of Near-Earth Asteroids (NEAs), and the establishment of a permanent human presence on the Moon. Beyond the logistical and technical challenges this poses, there’s been no shortage of concern about the legal issues and implications this will raise as well.

To this end, a group of legal scholars and space experts recently came together to form the Space Court Foundation (SCF), a non-profit educational organization created to foster a conversation about these and other related space issues. By beginning the conversation now, they hope, the public will be able to play an active role in the burgeoning and evolving domain known as “space law.”

Continue reading “The Space Court Foundation is Now in Session!”NASA Will Pay You to Retrieve Regolith and Rocks from the Moon

As part of Project Artemis, NASA intends to send the first woman and the next man to the Moon by 2024, in what will be the first crewed mission to the lunar since the Apollo Era. By the end of the decade, NASA also hopes to have all the infrastructure in place to create a program for “sustainable lunar exploration,” which will include the Lunar Gateway (a habitat in orbit) and the Artemis Base Camp (a habitat on the surface).

Part of this commitment entails the recovery and use of resources that are harvested locally, including regolith to create building materials and ice to create everything from drinking water to rocket fuel. To this end, NASA has asked its commercial partners to collect samples of lunar soil or rocks as part of a proof-of-concept demonstration of how they will scout and harvest natural resources and conduct commercial operations on the Moon.

Continue reading “NASA Will Pay You to Retrieve Regolith and Rocks from the Moon”NASA Proposes the Artemis Accords. The New Rules for Lunar Exploration

As part of Project Artemis, which was announced in May of 2019, NASA will be sending the first woman and the next man to the Moon for the first time since the Apollo Era. To make this happen, NASA has partnered with the private aerospace industry to develop all the necessary systems. At the same time, NASA has entered into collaborative agreements with other space agencies to ensure that lunar exploration is open to all.

To formalize these agreements and ensure that all parties are committed to the same goals, NASA recently drafted a framework for cooperative lunar exploration and development. Known as the Artemis Accords, this series of bilateral agreements (which are grounded in the Outer Space Treaty of 1967) establish common principles for international partners who want to become part of humanity’s long-awaited return to the Moon.

Continue reading “NASA Proposes the Artemis Accords. The New Rules for Lunar Exploration”Need a Job? NASA is Looking for a New Planetary Protection Officer

NASA has always had its fingers in many different pies. This should come as no surprise, since the advancement of science and the exploration of the Universe requires a multi-faceted approach. So in addition to studying Earth and distant planets, the also study infectious diseases and medical treatments, and ensuring that food, water and vehicles are safe. But protecting Earth and other planets from contamination, that’s a rather special job!

For decades, this responsibility has fallen to the NASA Office of Planetary Protection, the head of which is known as the Planetary Protection Officer (PPO). Last month, NASA announced that it was looking for a new PPO, the person whose job it will be to ensure that future missions to other planets don’t contaminate them with microbes that have come along for the ride, and that return missions don’t bring extra-terrestrial microbes back to Earth.

Since the beginning of the Space Age, federal agencies have understood that any and all missions carried with them the risk of contamination. Aside from the possibility that robotic or crewed missions might transport Earth microbes to foreign planets (and thus disrupt any natural life cycles there), it was also understood that missions returning from other bodies could bring potentially harmful organisms back to Earth.

As such, the Office of Planetary Protection was established in 1967 to ensure that these risks were mitigated using proper safety and sterilization protocols. This was shortly after the United Nation’s Office of Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) drafted the Outer Space Treaty, which was signed by the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union (as of 2017, 107 countries have become party to the treaty).

The goals of the Office of Planetary Protection are consistent with Article IX of the Outer Space Treaty; specifically, the part which states:

“States Parties to the Treaty shall pursue studies of outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, and conduct exploration of them so as to avoid their harmful contamination and also adverse changes in the environment of the Earth resulting from the introduction of extraterrestrial matter and, where necessary, shall adopt appropriate measures for this purpose.”

The office and its practices are also consistent with NASA’s internal policies. These include NASA Policy Directive (NPR) 8020.12D: “Planetary Protection Provisions for Robotic Extraterrestrial Missions”, and 8020.7: “Biological Contamination Control for Outbound and Inbound Planetary Spacecraft”, which require that all missions comply with protection procedures.

For decades, these directives have been followed to ensure that missions to the Moon, Mars and the Outer Solar System did not threaten these extra-terrestrial environments. For example, after eight years studying Jupiter and its largest moons, the Galileo probe was deliberately crashed into Jupiter’s atmosphere to ensure that none of its moons (which could harbor life beneath their icy surfaces) were contaminated by Earth-based microbes.

The same procedure will be followed by the Juno mission, which is currently in orbit around Jupiter. Barring a possible mission extension, the probe is scheduled to be deorbited after conducting a total of 12 orbits of the gas giant. This will take place in July of 2018, at which point, the craft will burn up to avoid contaminating the Jovian moons of Europa, Ganymede and Callisto.

The same holds true for the Cassini spacecraft, which is currently passing between Saturn and its system of rings, as part of the mission’s Grand Finale. When this phase of its mission is complete – on September 15th, 2017 – the probe will be deorbited into Saturn’s atmosphere to prevent any microbes from reaching Enceladus, Titan, Dione, moons that may also support life in their interiors (or in Titan’s case, even on its surface!)

To be fair, the position of a Planetary Protection Officer is not unique to NASA. The European Space Agency (ESA), the Japanese Aerospace and Exploration Agency (JAXA) and other space agencies have similar positions. However, it is only within NASA and the ESA that it is considered to be a full-time job. The position is held for three years (with a possible extension to five) and is compensated to the tune of $124,406 to $187,000 per year.

The job, which can be applied for on USAJOBS.gov (and not through the Office of Planetary Protection), will remain open until August 18th, 2017. According to the posting, the PPO will be responsible for:

- Leading planning and coordinating activities related to NASA mission planetary protection needs.

- Leading independent evaluation of, and providing advice regarding, compliance by robotic and human spaceflight missions with NASA planetary protection policies, statutory requirements and international obligations.

- Advising the Chief, SMA and other officials regarding the merit and implications of programmatic decisions involving risks to planetary protection objectives.

- In coordination with relevant offices, leading interactions with COSPAR, National Academies, and advisory committees on planetary protection matters.

- Recommending and leading the preparation of new or revised NASA standards and directives in accordance with established processes and guidelines.

What’s more, the fact that NASA is advertising the position is partly due to some recent changes to the role. As Catharine Conley*, NASA’s only planetary protection officer since 2014, indicated in a recent interview with Business Insider: “This new job ad is a result of relocating the position I currently hold to the Office of Safety and Mission Assurance, which is an independent technical authority within NASA.”

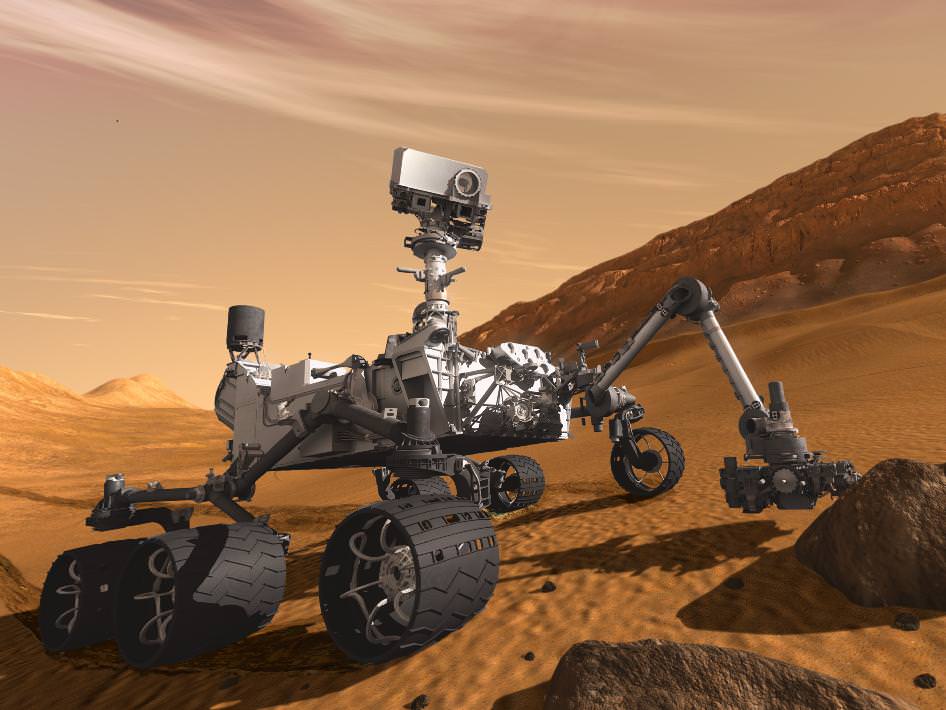

While the position has been undeniably important in the past, it is expected to become of even greater importance given NASA’s planned activities for the future. This includes NASA’s proposed “Journey to Mars“, a crewed mission which will see humans setting foot on the Red Planet sometime in the 2030s. And in just a few years time, the Mars 2020 rover is scheduled to begin searching the Martian surface for signs of life.

As part of this mission, the Mars 2020 rover will collect soil samples and place them in a cache to be retrieved by astronauts during the later crewed mission. Beyond Mars, NASA also hopes to conduct mission to Europa, Enceladus and Titan to look for signs of life. Each of these worlds have the necessary ingredients, which includes the prebiotic chemistry and geothermal energy necessary to support basic lifeforms.

Given that we intend to expand our horizons and explore increasingly exotic environments in the future – which could finally lead to the discovery of life beyond Earth – it only makes sense that the role of the Planetary Protection Officer become more prominent. If you think you’ve got the chops for it, and don’t mind a six-figure salary, be sure to apply soon!

*According to BI, Conley has not indicated if she will apply for the position again.

Further Reading: Business Insider, USAJOBS

Can you buy Land on the Moon?

Have you ever heard that it’s possible to buy property on the Moon? Perhaps someone has told you that, thanks to certain loopholes in the legal code, it is possible to purchase your very own parcel of lunar land. And in truth, many celebrities have reportedly bought into this scheme, hoping to snatch up their share of land before private companies or nations do.

Despite the fact that there may be several companies willing to oblige you, the reality is that international treaties say that no nation owns the Moon. These treaties also establish that the Moon is there for the good of all humans, and so it’s impossible for any state to own any lunar land. But does that mean private ownership is impossible too? The short answer is yes.

The long answer is, it’s complicated. At present, there are multiple nations hoping to build outposts and settlements on the Moon in the coming decades. The ESA hopes to build a “international village” between 2020 and 2030 and NASA has plans for its own for a Moon base.

The Russian space agency (Roscosmos) is planning to build a lunar base by the 2020s, and the China National Space Agency (CNSA) is planning to build such a base in a similar timeframe, thanks to the success of its Chang’e program.

Because of this, a lot of attention has been focused lately on the existing legal framework for the Moon and other celestial bodies. Let’s take a look at the history of “space law”, shall we?

Outer Space Treaty:

On Jan. 27th, 1967, the United States, United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union sat down together to work out a treaty on the exploration and use of outer space. With the Soviets and Americans locked in the Space Race, there was fear on all sides that any power that managed to put resources into orbit, or get to the Moon first, might have an edge on the others – and use these resources for evil!

As such, all sides signed “The Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies” – aka. “The Outer Space Treaty”. This treaty went into effect on Oct. 10th, 1967, and became the basis of international space law. As of September 2015, it has been signed by 104 countries (while another 24 have signed the treaty but have not competed the ratification process).

The treaty is overseen the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA). It’s a big document, with lots of articles, subsections, and legalese. But the most relevant clause is Article II of the treaty, where it states:

“Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.”

“Loophole” in the Treaty:

Despite clearly saying that Outer Space is the property of all humanity, and can only be used for the good of all, the language is specific to national ownership. As a result, there is no legal consensus on whether or not the treaty’s prohibition are also valid as far as private appropriation is concerned.

However, Article II addresses only the issue of national ownership, and contains no specific language about the rights of private individuals or bodies in owning anything in outer space. Because of this, there are some who have argued that property rights should be recognized on the basis of jurisdiction rather than territorial sovereignty.

Looking to Article VI though, it states that governments are responsible for the actions of any party therein. So it is clear that the spirit of the treaty is meant to apply to all entities, be they public or private. As it states:

“States Parties to the Treaty shall bear international responsibility for national activities in outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, whether such activities are carried on by governmental agencies or by non-governmental entities, and for assuring that national activities are carried out in conformity with the provisions set forth in the present Treaty. The activities of non-governmental entities in outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, shall require authorization and continuing supervision by the appropriate State Party to the Treaty.”

In other words, any person, organization or company operating in space is answerable to their respective government. But since no specific mention is made of private ownership, there are those who claim that this represents a “loophole” in the treaty which allows them to claim and sell land on the Moon at this time. Because of this ambiguity, there have been attempts to augment the Outer Space Treaty.

The Moon Treaty:

On Dec. 18th, 1979, members of the United Nations presented an agreement which was meant to be a follow-up to the Outer Space Treaty and close its supposed loopholes. Known as the “Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies” – aka. “The Moon Treaty” or “Moon Agreement” – this treaty intended to establish a legal framework for the use of the Moon and other celestial bodies.

Much like the Outer Space Treaty, the agreement established that the Moon should be used for the benefit of all humanity and not for the sake of any individual state. The treaty banned weapons testing, declared that any scientific research must be open and shared with the international community, and that nations and individuals and organizations could not claim anything.

In practice, the treaty failed because it has not been ratified by any state that engages in crewed space exploration or has domestic launch capability. This includes the United States, the larger members of the ESA, Russia, China, Japan and India. Though it expressly forbids both national and private ownership of land on the Moon, or the use thereof for non-scientific, non-universal purposes, the treaty effectively has no teeth.

Bottom line, there is nothing that expressly forbids companies from owning land on the Moon. However, with no way to claim that land, anyone attempting to sell land to prospective buyers is basically selling snake oil. Any documentation that claims you own land on the Moon is unenforceable, and no nation on the planet that has signed either the Outer Space Treaty or the Moon Treaty will recognize it.

Then again, if you were able to fly up to the Moon and build a settlement there, it would be pretty difficult for anyone to stop you. But don’t expect that to the be the last word on the issue. With multiple space agencies looking to create “international villages” and companies hoping to create a tourist industry, you could expect some serious legal battles down the road!

But of course, this is all academic. With no atmosphere to speak of, temperatures reaching incredible highs and lows – ranging from 100 °C (212 °F) to -173 °C (-279.4 °F) – its low gravity (16.5 % that of Earth), and all that harsh Moon dust, nobody outside of trained astronauts (or the clinically insane) should want to spend a significant amount of time there!

We have written many interesting articles about the Moon here at Universe Today. Here’s Can you Really Name a Star?, Make a Deal for Land on the Moon, and our series on Building a Moon Base.

Want more information about the Moon? Here’s NASA’s Lunar and Planetary Science page. And here’s NASA’s Solar System Exploration Guide.

You can listen to a very interesting podcast about the formation of the Moon from Astronomy Cast, Episode 17: Where Did the Moon Come From?

Sources:

SpaceX Calls In The Lawyers For 2018 Mars Shot

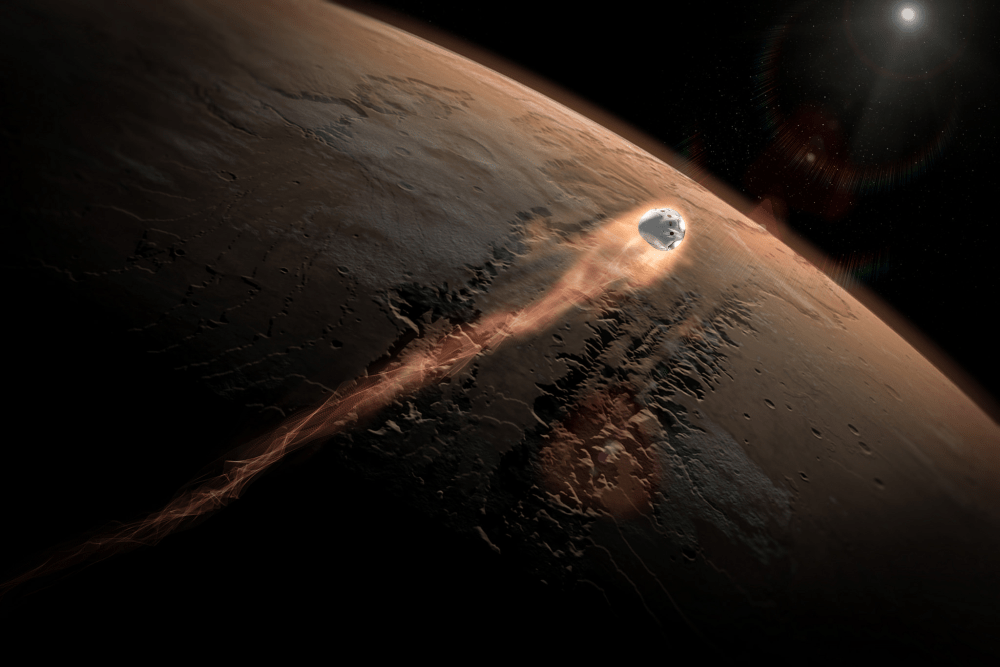

A manned mission to Mars is a hot topic in space, and has been for a long time. Most of the talk around it has centred on the required technology, astronaut durability, and the overall feasibility of the mission. But now, some of the talk is focussing on the legal framework behind such a mission.

In April 2016, SpaceX announced their plans for a 2018 mission to Mars. Though astronauts will not be part of the mission, several key technologies will be demonstrated. SpaceX’s Dragon capsule will make the trip to Mars, and will conduct a powered, soft landing on the surface of the red planet. The capsule itself will be launched by another new piece of technology, SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket.

It’s a fascinating development in space exploration; a private space company, in cooperation with NASA, making the trip to Mars with all of its own in-house technology. But above and beyond all of the technological challenges, there is the challenge of making the whole endeavour legal.

Though it’s not widely known or talked about, there are legal implications to launching things into space. In the US, each and every launch by a private company has to have clearance from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

That’s because the US signed the Outer Space Treaty in 1969, a treaty that sets out the obligations and limitations to activities in space. The FAA has routinely given their ascent to commercial launches, but things may be starting to get a little tricky in space.

The most recent Humans To Mars Summit, a conference focussed on Mars missions and explorations, just wrapped up on May 19th. At that conference, George Nield, associate administrator for commercial space transportation at the FAA, addressed the issue. “That’ll be an FAA licensed launch as well,” said Nield of the SpaceX mission to Mars. “We’re already working with SpaceX on that mission,” he added. “There are some interesting policy questions that have to do with the Outer Space Treaty,” said Nield.

The Outer Space Treaty was signed in 1967, and has some sway over space exploration and colonization. Though it gives wide latitude to governments that are exploring space, how it will affect commercial activity like resource exploitation, and installations like settlements in other planets, is not so clear.

According to Nield, the FAA is interested in Article VI of the treaty and how it might impact SpaceX’s planned mission to Mars. Article VI states that all signees to the treaty “shall bear international responsibility for national activities in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, whether such activities are carried on by governmental agencies or by non-governmental entities.”

Article VI also says, “the activities of non-governmental entities in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, shall require authorization and continuing supervision by the appropriate State Party to the Treaty.”

What this language means is that the US government itself will bear responsibility for the SpaceX Mars mission. Obviously, this kind of treaty obligation is important. There isn’t exactly a huge list of private companies exploring space, but that will change as the years pass. It seems likely that the bulk of commercial space exploration and resource utilization will be centred in the US, so how the US deals with their treaty obligations will be of immense interest now and in the future.

The treaty itself is mostly focused on avoiding military activity in space. It prohibits things like weapons of mass destruction in space, and weapons testing or military bases on the Moon or other celestial bodies. The treaty also states that the Moon and other planets and bodies cannot be claimed by any nation, and that these and other bodies “are the common heritage of mankind.” Good to know.

Taken as a whole, it’s easy to see why the Treaty is important. Space can’t become a free-for-all like Earth has been in the past. There has to be some kind of framework. “A government needs to oversee these non-governmental activities,” according to Nield.

There’s another aspect to all of this. Governments routinely sign treaties, and then try to figure out ways around them, while hoping their rivals won’t do the same. It’s a sneaky, tactical business, because governments can’t grossly ignore treaties, else the other co-signatories abandon said treaty completely. A case in point is last year’s law, signed by the US Congress, which makes it legal for companies to mine asteroids. This law could be interpreted as violating the Treaty.

Governments can claim, for instance, that their activities are scientific rather than military. Geo-political influence depends greatly on projecting power. If one nation can project power into space, while claiming their activities are scientific rather than military, they will gain an edge over their rivals. Countries also seek to bend the rules of a treaty to satisfy their own interests, while preventing other countries from doing the same. Just look at history.

We’re not in that type of territory yet. So far, no nation has had an opportunity to really violate the treaty, though the asteroid mining law passed by the US Congress comes close.

The SpaceX mission to Mars is a very important one, in terms of how the Outer Space Treaty will be tested and adhered to. More and more countries, and private companies, are becoming space-farers. The legality of increasingly complex missions in space, and the eventual human presence on the Moon and Mars, is a fascinating one not usually addressed by the space science community.

We in the space science community are primarily interested in technological advances, and in the frontiers of human knowledge. It might be time for us to start paying attention to the legal side of things. Space exploration could turn out to have an element of courtroom drama to it.

ESA Planning To Build An International Village… On The Moon!

With all the talk about manned missions to Mars by the 2030s, its easy to overlook another major proposal for the next great leap. In recent years, the European Space Agency has been quite vocal about its plan to go back to the Moon by the 2020s. More importantly, they have spoken often about their plans to construct a moon base, one which would serve as a staging platform for future missions to Mars and beyond.

These plans were detailed at a recent international symposium that took place on Dec. 15th at the the European Space Research and Technology Center in Noordwijk, Netherlands. During the symposium, which was titled “Moon 2020-2030 – A New Era of Coordinated Human and Robotic Exploration”, the new Director General of the ESA – Jan Woerner – articulated his agency’s vision.

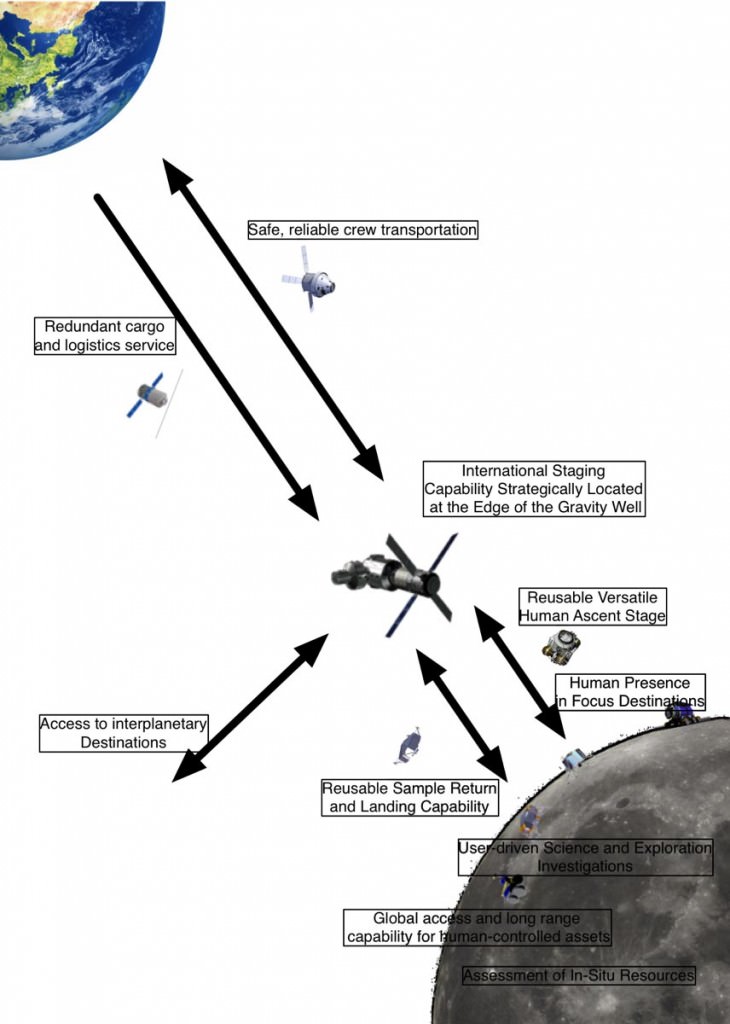

The purpose of the symposium – which saw 200 scientists and experts coming together to discuss plans and missions for the next decade – was to outline common goals for lunar exploration, and draft methods on how these can be achieved cooperatively. Intrinsic to this was the International Space Exploration Coordinated Group‘s (ISECG) Global Exploration Roadmap, an agenda for space exploration that was drafted by the group’s 14 members – which includes NASA, the ESA, Roscosmos, and other federal agencies.

This roadmap not only lays out the strategic significance of the Moon as a global space exploration endeavor, but also calls for a shared international vision on how to go about exploring the Moon and using it as a stepping stone for future goals. When it came time to discuss how the ESA might contribute to this shared vision, Woerner outlined his agency’s plan to establish an international lunar base.

In the past, Woerner has expressed his interest in a base on the Moon that would act as a sort of successor to the International Space Station. Looking ahead, he envisions how an international community would live and perform research in this environment, which would be constructed using robotic workers, 3D printing techniques, and in-situ resources utilization.

The construction of such a base would also offer opportunities to leverage new technologies and forge lucrative partnerships between federal space agencies and private companies. Already, the ESA has collaborated with the architectural design firm Foster + Partners to come up with the plan for their lunar village, and other private companies have also been recruited to help investigate other aspects of building it.

Going forward, the plan calls for a series of manned missions to the Moon beginning in the 2020s, which would involve robot workers paving the way for human explorers to land later. These robots would likely be controlled through telepresence, and would combine lunar regolith with magnesium oxide and a binding salt to print out the shield walls of the habitat.

At present, the plan is for the base to be built in southern polar region, which exists in a near-state of perpetual twilight. Whether or not this will serve as a suitable location will be the subject of the upcoming Lunar Polar Sample Return mission – a joint effort between the ESA and Roscosmos that will involve sending a robotic probe to the Moon’s South Pole-Aitken Basin by 2020 to retrieve samples of ice.

This mission follows in the footsteps of NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), which showed that the Shakleton crater – located in the Moon’s southern polar region – has an abundant supply of water ice. This could not only be used to provide the Moon base with a source of drinking water, but could also be converted into hydrogen to refuel spacecraft on their way to and from Earth.

As Woerner was quoted as saying by the Daily Mail during the course of the symposium, this lunar base would provide the opportunity for scientists from many different nations to live and work together:

The future of space travel needs a new vision. Right now we have the Space Station as a common international project, but it won’t last forever. If I say Moon Village, it does not mean single houses, a church, a town hall and so on… My idea only deals with the core of the concept of a village: people working and living together in the same place. And this place would be on the Moon. In the Moon Village we would like to combine the capabilities of different spacefaring nations, with the help of robots and astronauts. The participants can work in different fields, perhaps they will conduct pure science and perhaps there will even be business ventures like mining or tourism.

Naturally, the benefits would go beyond scientific research and international cooperation. As NexGen Space LLC (a consultant company for NASA) recently stated, such a base would be a major stepping stone on the way to Mars. In fact, the company estimated that if such a base included refueling stations, it could cut the cost of any future Mars missions by about $10 billion a year.

And of course, a lunar base would also yield valuable scientific data that would come in handy for future missions. Located far from Earth’s protective magnetic field, astronauts on the Moon (and in circumpolar obit) would be subjected to levels of cosmic radiation that astronauts in orbit around Earth (i.e. aboard the ISS) are not. This data will prove immeasurably useful when plotting upcoming missions to Mars or into deep space.

An additional benefit is the possibility of creating an international presence on the Moon that would ensure that the spirit of the Outer Space Treaty endures. Signed back in 1966 at the height of the “Moon Race”, this treaty stated that “the exploration and use of outer space shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries and shall be the province of all mankind.”

In other words, the treaty was meant to ensure that no nation or space agency could claim anything in space, and that issues of territorial sovereignty would not extend to the celestial sphere. But with multiple agencies discussing plans to build bases on the Moon – including NASA, Roscosmos, and JAXA – it is possible that issues of “Moon sovereignty” might emerge at some point in the future.

And having a base that could facilitate regular trips to the Moon would also be a boon for the burgeoning space tourism industry. Beyond offering trips into Low Earth Orbit (LEO) aboard Virgin Galactic, Richard Branson has also talked about the possibility of offering trips to the Moon by 2043. Golden Spike, another space tourism company, also hopes to offer round-trip lunar adventures someday (at a reported $750 million a pop).

Other private space ventures that are looking to make the Moon a tourist destination include Space Adventures and Excalibur Almaz – both of which are hoping to offer lunar fly-bys (no Moon walks, sorry) for $150 million apiece someday. Many analysts predict that in the coming decade, this industry will begin to (no pun intended) take flight. As such, establishing infrastructure there ahead of time would certainly be beneficial.

“We’re going back to the Moon”. That appeared to be central the message behind the recent symposium and the ESA’s plans for future space exploration. And this time, it seems, we will be staying there! And from there, who knows? The Universe is a big place…

Further Reading: European Space Agency