Have you ever wondered how much water it would take to put out the Sun? It turns out, the Sun isn’t on fire. So what would happen if you did try to hit the Sun with a tremendous amount of water?

How much water would it take to extinguish the Sun? I recently saw this great question on Reddit, and I couldn’t resist taking a crack at it: We know that the question doesn’t make a lot of sense.

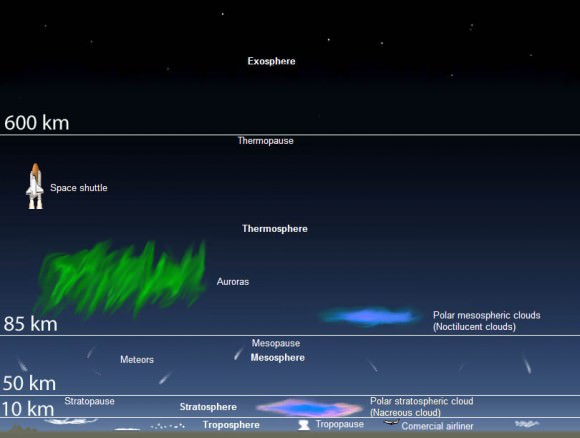

A fire is a chemical reaction, where material releases heat as it oxidizes. If you take away oxygen from a fire, it goes out. But.. there’s no oxygen in space, it’s a vacuum. So, there’s not a whole lot of room for regular flavor water-extinguishable fire in space. You know this. How many times have we had to seal off the living quarters and open the bay doors to vent all the oxygen in the space because there was a fire in the cargo bay? We have to do that, like, all the time.

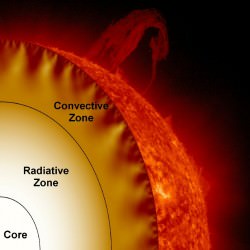

Our wonderful Sun is something quite different. It’s a nuclear fusion reaction, converting hydrogen atoms into helium under the immense temperatures and pressures at its core. It doesn’t need oxygen to keep producing energy. It’s already got its fuel baked in. All the Sun needs is our adoration, quiet, and yet ever present fear. Only if we constantly pray will it be happy and perhaps we’ll go another day where it doesn’t hurl a giant chunk of itself at our smug little faces because it’s tired of our shenanigans.

So, I’m still going to take a swing at this question… so let’s talk about what would happen if you did pour a tremendous amount of water on the Sun? Let’s say another Sun’s worth of H20. Conveniently, Hydrogen is what the Sun uses for fuel, so if you give the Sun more hydrogen, it should just get larger and hotter.

Oxygen is one of the byproducts of fusion. Right now, our Sun is turning hydrogen into helium using the proton-proton fusion reaction. But there’s another type of reaction that happens in there called the carbon-nitrogen-oxygen reaction. As of right now, only 0.8% of the Sun’s fusion reactions proceed along this path.

So if you fed the Sun more oxygen as part of the water, it would allow it to perform more of these fusion reactions too. For stars which are 1.3 times the mass of the Sun, this CNO reaction is the main way fusion is taking place. So, if we did dump a giant pile of water onto the Sun, we’d just be making Sun bigger and hotter.

Conveniently, larger hotter stars burn for a shorter amount of time before they die. The largest, most massive stars only last a few million years and then they explode as supernovae. So, if you’re out to destroy the Sun, and you’re playing a really, really long game, this might actually be a viable route.

I’m pretty sure that wasn’t the intent though. Let’s say we just want to snuff out the Sun. Vsauce provides a strategy for this. If you could somehow blast your water at the Sun at high enough velocity, you might be able to tear it apart. If you can reduce the Sun’s mass, you can decrease the temperature and pressure in its core so that it can no longer support fusion reactions.

I’m going to sum up. The Sun isn’t on fire. There’s no amount of water you could add that would quench it, you’d just make it explode, but if you used firehoses that could spray water at nearly the speed of light, you could probably shut the thing off and eventually freeze us all, which is what I think you were hoping for in the first place.

What do you think? What else could we do to snuff out the Sun?