Neutrinos are some of the most abundant, curious, and elusive critters in particle physics. Incredibly lightweight — nigh massless, according to the Standard Model — as well as chargeless, they zip around the Universe at the speed of light and they don’t interact with any other particles. Some of them have been around since the Big Bang and, just as you’ve read this, trillions of them have passed through your body (and more are on the way.) But despite their ubiquitousness neutrinos are notoriously difficult to study precisely because they ignore pretty much everything made out of anything else. So it’s not surprising that weighing a neutrino isn’t as simple as politely asking one to step on a scale.

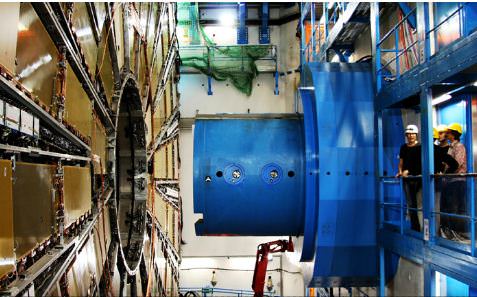

Thankfully particle physicists are a tenacious lot, including the ones at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermilab, and they aren’t giving up on their latest neutrino safari: the NuMI Off-Axis Electron Neutrino Appearance experiment, or NOvA. (Scientists represent neutrinos with the Greek letter nu, or v.) It’s a very small-game hunt to catch neutrinos on the fly, and it uses some very big equipment to do the job. And it’s already captured its first neutrinos — even before their setup is fully complete.

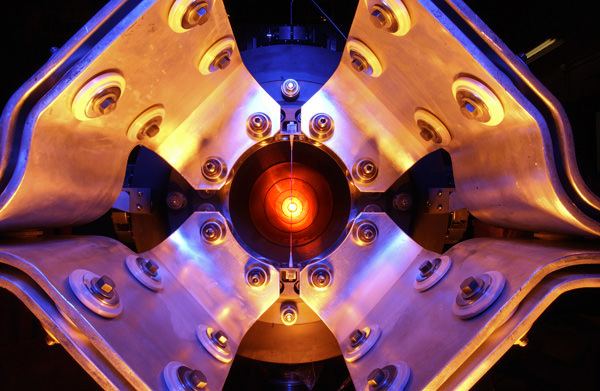

Created by smashing protons against graphite targets in Fermilab’s facility just outside Chicago, Illinois, resulting neutrinos are collected and shot out in a beam 500 miles northwest to the NOvA far detector in Ash River, Minnesota, located along the Canadian border. The very first beams were fired in Sept. 2013, while the Ash River facility was still under construction.

“That the first neutrinos have been detected even before the NOvA far detector installation is complete is a real tribute to everyone involved,” said University of Minnesota physicist Marvin Marshak, Ash River Laboratory director. “This early result suggests that the NOvA collaboration will make important contributions to our knowledge of these particles in the not so distant future.”

The beams from Fermilab are fired in two-second intervals, each sending billions of neutrinos directly toward the detectors. The near detector at Fermilab confirms the initial “flavor” of neutrinos in the beam, and the much larger far detector then determines if the neutrinos have changed during their three-millisecond underground interstate journey.

Again, because neutrinos don’t readily interact with ordinary particles, the beams can easily travel straight through the ground between the facilities — despite the curvature of the Earth. In fact the beam, which starts out 150 feet (45 meters) below ground near Chicago, eventually passes over 6 miles (10 km) deep during its trip.

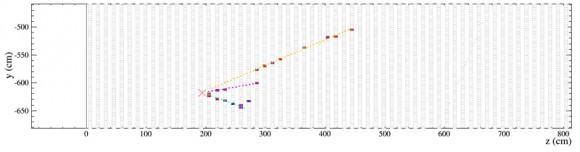

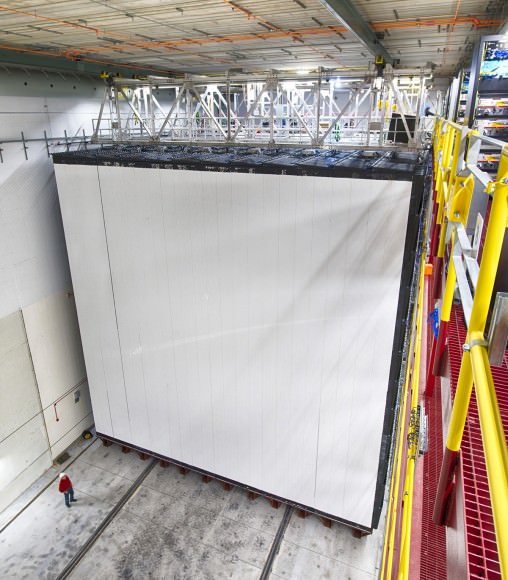

According to a press release from Fermilab, neutrinos “come in three types, called flavors (electron, muon, or tau), and change between them as they travel. The two detectors of the NOvA experiment are placed so far apart to give the neutrinos the time to oscillate from one flavor to another while traveling at nearly the speed of light. Even though only a fraction of the experiment’s larger detector, called the far detector, is fully built, filled with scintillator and wired with electronics at this point, the experiment has already used it to record signals from its first neutrinos.”

The 50-foot (15 m) tall detector blocks are filled with a liquid scintillator that’s made of 95% mineral oil and 5% liquid hydrocarbon called pseudocumene, which is toxic but “imperative to the neutrino-detecting process.” The mixture magnifies any light that hits it, allowing the neutrino strikes to be more easily detected and measured. (Source)

“NOvA represents a new generation of neutrino experiments,” said Fermilab Director Nigel Lockyer. “We are proud to reach this important milestone on our way to learning more about these fundamental particles.”

After completion this summer NOvA’s near and far detectors will weigh 300 and 14,000 tons, respectively.

The goal of the NOvA experiment is to successfully capture and measure the masses of the different neutrino flavors and also determine if neutrinos are their own antiparticles (they could be the same, since they lack specific charge.) By comparing the oscillations (i.e., flavor changes) of muon neutrino beams vs. muon antineutrino beams fired from Fermilab, scientists hope to determine their mass hierarchy — and ultimately discover why the Universe currently contains much more matter than antimatter.

Read more: Neutrino Detection Could Help Paint an Entirely New Picture of the Universe

Once the experiment is fully operational scientists expect to catch a precious few neutrinos every day — about 5,000 total over the course of its six-year run. Until then, they at least now have their first few on the books.

“Seeing neutrinos in the first modules of the detector in Minnesota is a major milestone. Now we can start doing physics.”

– Rick Tesarek, Fermilab physicist

Learn more about the development and construction of the NoVA experiment below:

(Video credit: Fermilab)

Find out more about the NOvA research goals here.

Source: Fermilab press release

The NOvA collaboration is made up of 208 scientists from 38 institutions in the United States, Brazil, the Czech Republic, Greece, India, Russia and the United Kingdom. The experiment receives funding from the U.S. Department of Energy, the National Science Foundation and other funding agencies.