[/caption]

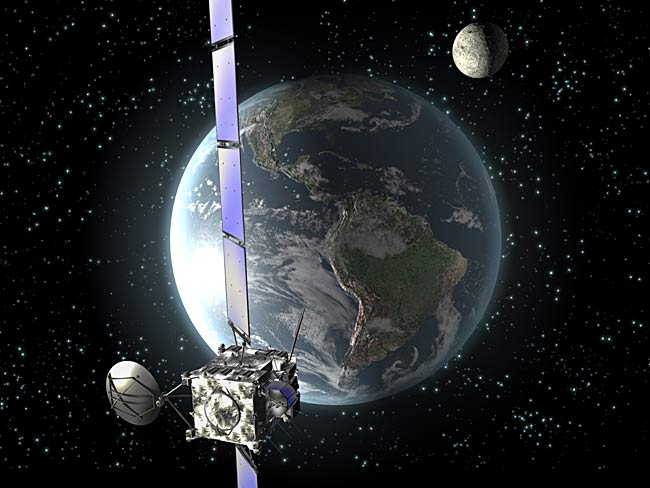

Those who are interested in black holes are familiar with the event horizon, but the Chandra X-Ray Observatory is giving us an even more detailed look into the structure surrounding these enigmas by imaging the inflowing hot gases. Galaxy NGC 3115 contains a supermassive black hole at its heart and for the first time astronomers have evidence of a critical threshold known as the “Bondi radius”.

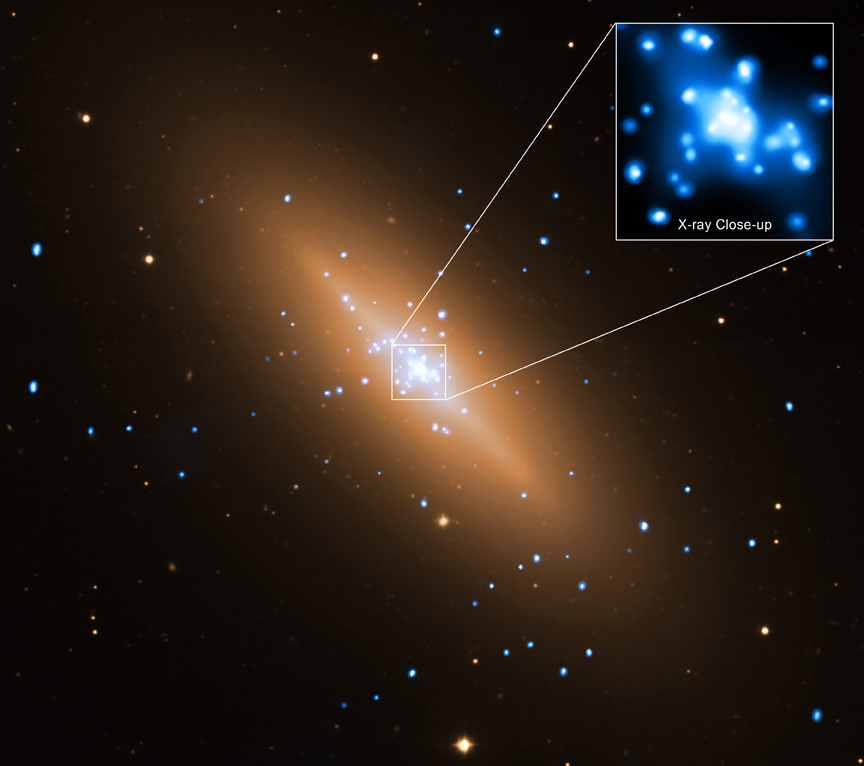

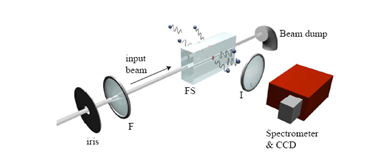

Located approximately 32 million light years from the Solar System in the constellation of Sextans, NGC 3115 is a prime candidate for study. Contained in its nucleus is a billion-solar-mass black hole which is stripping away hot gases from nearby stars which can be imaged in X-ray. “The Chandra data are shown in blue and the optical data from the VLT are colored gold. The point sources in the X-ray image are mostly binary stars containing gas that is being pulled from a star to a stellar-mass black hole or a neutron star. The inset features the central portion of the Chandra image, with the black hole located in the middle.” says the team. “No point source is seen at the position of the black hole, but instead a plateau of X-ray emission coming from both hot gas and the combined X-ray emission from unresolved binary stars is found.”

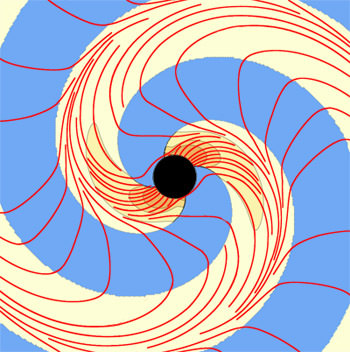

In order to see the machination of the black hole at work, the Chandra team eradicated the signal given off by the binary stars, separating it from the super-heated gas flow. By observing the gas at varying distances the team could then pinpoint a threshold where the gas first becomes impacted by the supermassive black hole’s gravity and begins moving towards the center. This point is known as the Bondi radius.

“As gas flows toward a black hole it becomes squeezed, making it hotter and brighter, a signature now confirmed by the X-ray observations. The researchers found the rise in gas temperature begins at about 700 light years from the black hole, giving the location of the Bondi radius.” says the Chandra team. “This suggests that the black hole in the center of NGC 3115 has a mass of about two billion times that of the Sun, supporting previous results from optical observations. This would make NGC 3115 the nearest billion-solar-mass black hole to Earth.”

Original Story Source: Chandra News Further Reading: Resolving the Bondi Accretion Flow toward the Supermassive Black Hole of NGC 3115 with Chandra.