In their drive to set exploration goals for the future, NASA’s Discovery Program put out the call for proposals for their thirteenth Discovery mission in February 2014. After reviewing the 27 initial proposals, a panel of NASA and other scientists and engineers recently selected five semifinalists for additional research and development, one or two of which will be launching by the 2020s.

With an eye to Venus, near-Earth objects and asteroids, these missions are looking beyond Mars to address other questions about the history and formation of our Solar System. Among them is the proposed Psyche mission, a robotic spacecraft that will explore the metallic asteroid of the same name – 16 Psyche – in the hopes of shedding some light on the mysteries of planet formation.

Discovered by Italian astronomer Annibale de Gasparis on March 17th, 1852 – and named after a Greek mythological figure – Psyche is one the ten most-massive asteroids in the Asteroid Belt. It is also the most massive M-type asteroid, a special class pertaining to asteroids composed primarily of nickel and iron.

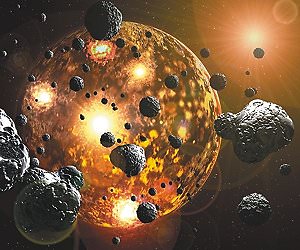

For some time, scientists have speculated that this metallic asteroid is in fact the survivor of a protoplanet. In this scenario, a violent collision with a planetesimal stripped off Psyche’s outer, rocky layers, leaving behind only the dense, metallic interior. This theory is supported by estimates of Psyche’s bulk density, spectra, and radar surface properties; all of which show it to be an object unlike any others in the Belt.

In addition, this composition of 16 Psyche is strikingly similar to that of Earth’s metal core. Given that astronomers think that larger planets like Venus, Earth and Mars formed from the collision and merger of smaller worlds, Psyche could be the remains of a protoplanet that did not get to create a larger body.

Had such a planetesimal been struck by a large enough object, it would have been able to lose its lower-mass exterior while keeping its core intact. Thus, studying this 250 km (155 mile) wide body, offers a unique opportunity to learn more about the interiors of planets and large moons, whose cores are hidden beneath many miles of rock.

Dr. Linda Elkins-Tanton of Arizona State University’s School of Earth and Space Exploration is the Principle Investigator of this mission. As she and her team stated in their mission proposal paper, which was originally submitted as part of the 45th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2014):

“This mission would be a journey back in time to one of the earliest periods of planetary accretion, when the first bodies were not only differentiating, but were being pulverized, shredded, and accreted by collisions. It is also an exploration, by proxy, of the interiors of terrestrial planets and satellites today: we cannot visit a metallic core any other way.

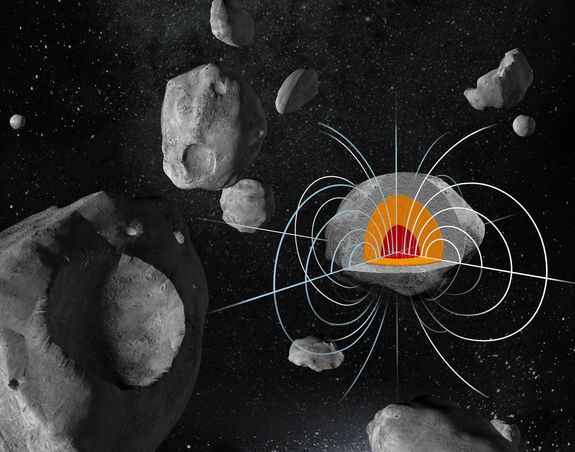

“For all of these reasons, coupled with the relative accessibility to low- cost rendezvous and orbit, Psyche is a superb target for a Discovery-class mission that would characterize its geology, shape, elemental composition, magnetic field , and mass distribution.”

A robotic mission to Pysche would also help astronomers learn more about metal worlds, a type of solar system object that scientists know very little about. But perhaps the greatest reason to study 16 Psyche is the fact that it is unique. So far, this body is the only metallic core-like body that has been discovered in the Solar System.

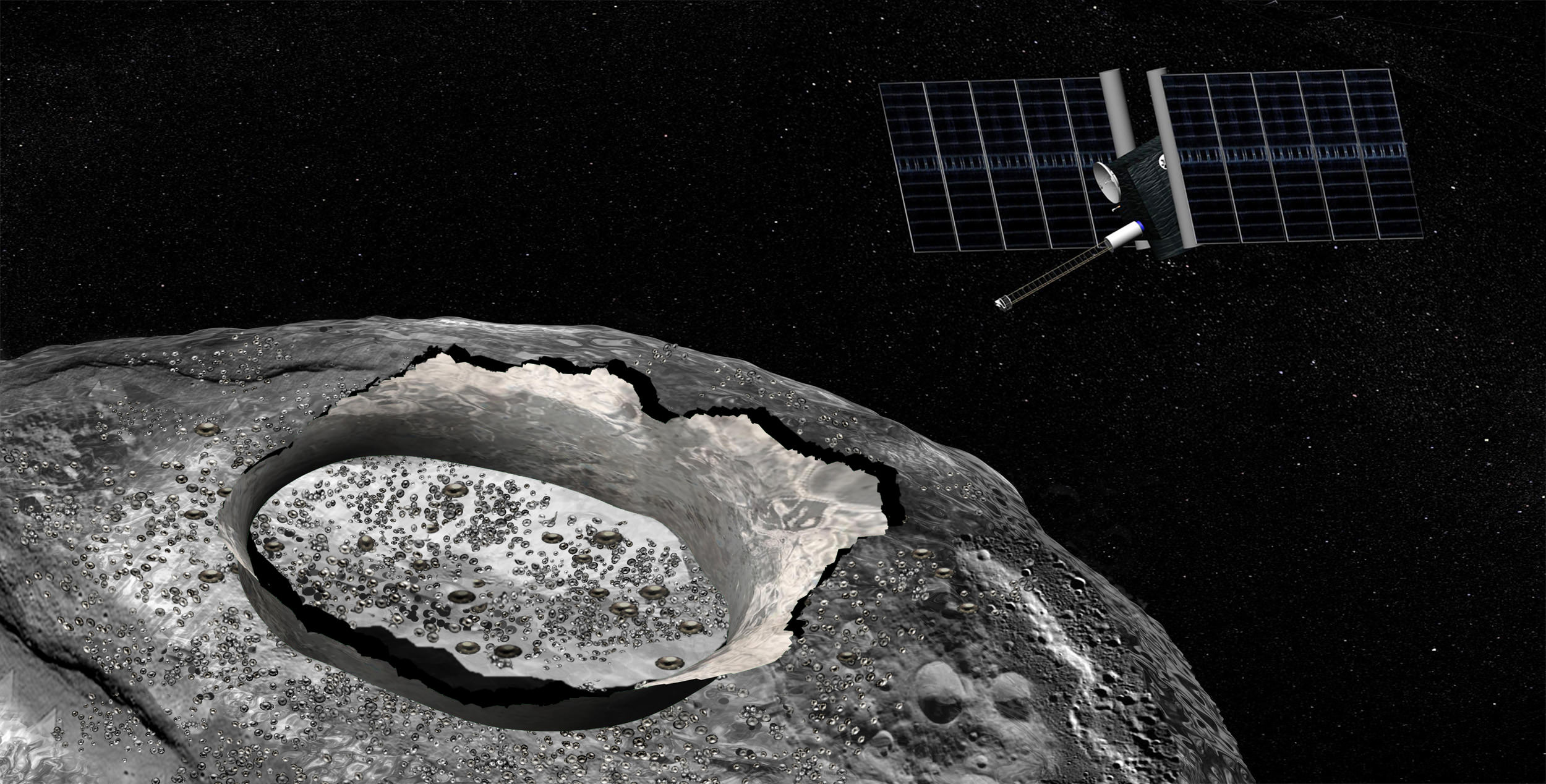

The proposed spacecraft would orbit Psyche for six months, studying its topography, surface features, gravity, magnetism, and other characteristics. The mission would also be cost-effective and quick to launch, since it is largely based on technology that went into the making of NASA’s Dawn probe. Currently in orbit around Ceres, the Dawn mission has demonstrated the effectiveness of many new technologies, not the least of which was the xenon ion thruster.

The Psyche orbiter mission was selected as one of the Discovery Program’s five semifinalists on September 30th, 2015. Each proposal has received $3 million for year-long studies to lay out detailed mission plans and reduce risks. One or two finalist will be selected to receive the program’s budget of $450 million (minus the cost of a launch vehicle and mission operations) and will launch in 2020 at the earliest.