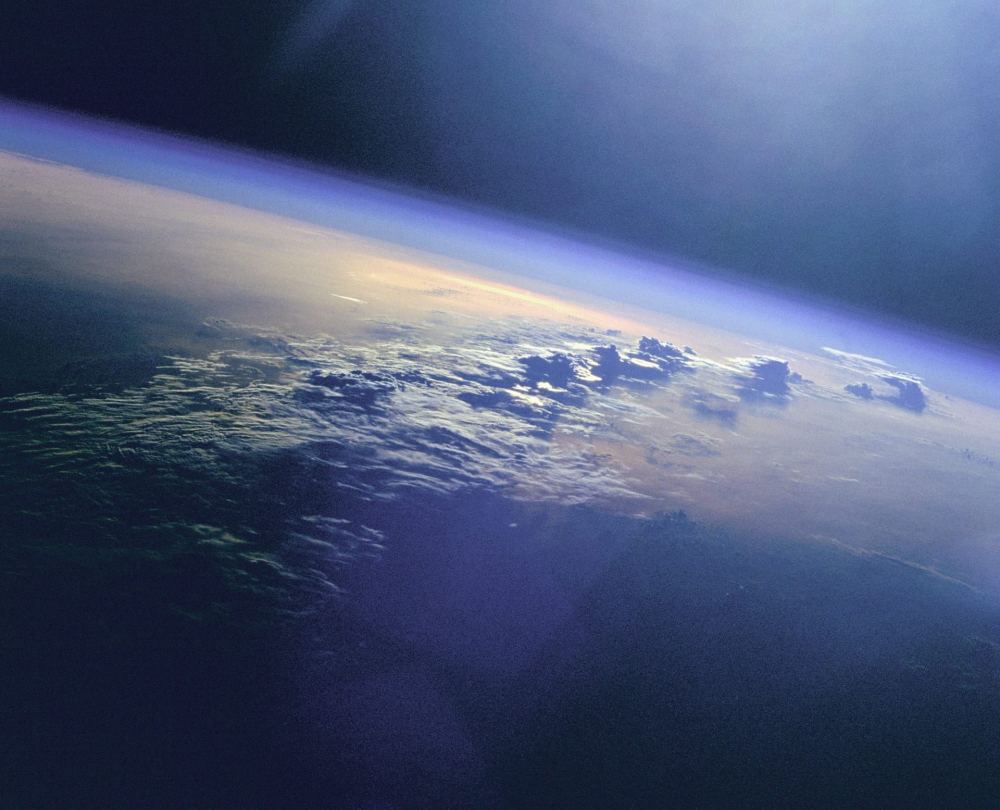

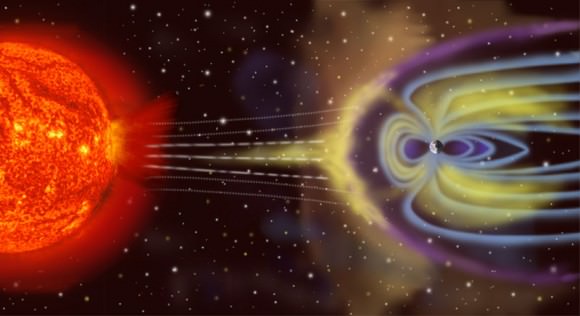

We here at Earth are fortunate that we have a viable atmosphere, one that is protected by Earth’s magnetosphere. Without this protective envelope, life on the surface would be bombarded by harmful radiation emanating from the Sun. However, Earth’s upper atmosphere is still slowly leaking, with about 90 tonnes of material a day escaping from the upper atmosphere and streaming into space.

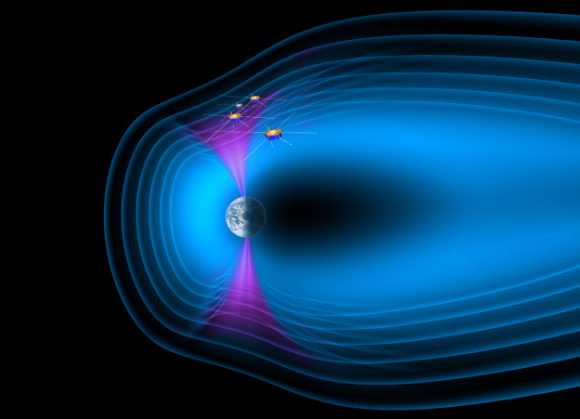

And although astronomers have been investigating this leakage for some time, there are still many unanswered questions. For example, how much material is being lost to space, what kinds, and how does this interact with solar wind to influence our magnetic environment? Such has been the purpose of the European Space Agency’s Cluster project, a series of four identical spacecraft that have been measuring Earth’s magnetic environment for the past 15 years.

Understanding our atmosphere’s interaction with solar wind first requires that we understand how Earth’s magnetic field works. For starters, it extends from the interior of our planet (and is believed to be the result of a dynamo effect in the core), and reaches all the way out into space. This region of space, which our magnetic field exerts influence over, is known as the magnetosphere.

The inner portion of this magnetosphere is called the plasmasphere, a donut-shaped region which extends to a distance of about 20,000 km from the Earth and co-rotates with it. The magnetosphere is also flooded with charged particles and ions that get trapped inside, and then are sent bouncing back and forth along the region’s field lines.

At its forward, Sun-facing edge, the magnetosphere meets the solar wind – a stream of charged particles flowing from the Sun into space. The spot where they make contact is known as the “Bow Shock”, which is so-named because its magnetic field lines force solar wind to take on the shape of a bow as they pass over and around us.

As the solar wind passes over Earth’s magnetosphere, it comes together again behind our planet to form a magnetotail – an elongated tube which contains trapped sheets of plasma and interacting field lines. Without this protective envelope, Earth’s atmosphere would have been slowly stripped away billions of years ago, a fate that is now believed to have befallen Mars.

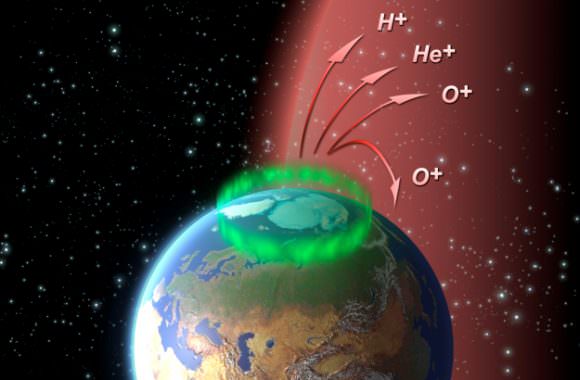

That being said, Earth’s magnetic field is not exactly hermetically sealed. For example, at our planet’s poles, the field lines are open, which allows solar particles to enter and fill our magnetosphere with energetic particles. This process is what is responsible for Aurora Borealis and Aurora Australis (aka. the Northern and Southern Lights).

At the same time, particles from Earth’s upper atmosphere (the ionosphere) can escape the same way, traveling up through the poles and being lost to space. Despite learning much about Earth’s magnetic fields and how plasma is formed through its interaction with various particles, much about the whole process has been unclear until quite recently.

As Arnaud Masson, ESA’s Deputy Project Scientist for the Cluster mission stated in an ESA press release:

“The question of plasma transport and atmospheric loss is relevant for both planets and stars, and is an incredibly fascinating and important topic. Understanding how atmospheric matter escapes is crucial to understanding how life can develop on a planet. The interaction between incoming and outgoing material in Earth’s magnetosphere is a hot topic at the moment; where exactly is this stuff coming from? How did it enter our patch of space?“

Given that our atmosphere contains 5 quadrillion tons of matter (that’s 5 x 1015, or 5,000,000 billion tons), a loss of 90 tons a day doesn’t amount to much. However, this number does not include the mass of “cold ions” that are regularly being added. This term is typically used to described the hydrogen ions that we now know are being lost to the magnetosphere on a regular basis (along with oxygen and helium ions).

Since hydrogen requires less energy to escape our atmosphere, the ions that are created once this hydrogen becomes part of the plasmasphere also have low energy. As a result, they have been very difficult to detect in the past. What’s more, scientists have only known about this flow of oxygen, hydrogen and helium ions – which come from the Earth’s polar regions and replenish plasma in the magnetosphere – for a few decades.

Prior to this, scientists believed that solar particles alone were responsible for plasma in Earth’s magnetosphere. But in more recent years, they have come to understand that two other sources contribute to the plasmasphere. The first are sporadic “plumes” of plasma that grow within the plasmasphere and travel outwards towards the edge of the magnetosphere, where they interact with solar wind plasma coming the other way.

The other source? The aforementioned atmospheric leakage. Whereas this consists of abundant oxygen, helium and hydrogen ions, the cold hydrogen ions appear to play the most important role. Not only do they constitute a significant amount of matter lost to space, and may play a key role in shaping our magnetic environment. What’s more, most of the satellites currently orbiting Earth are unable to detect the cold ions being added to the mix, something which Cluster is able to do.

In 2009 and in 2013, the Cluster probes were able to characterize their strength, as well as that of other sources of plasma being added to the Earth’s magnetosphere. When only the cold ions are considered, the amount of atmosphere being lost o space amounts to several thousand tons per year. In short, its like losing socks. Not a big deal, but you’d like to know where they are going, right?

This has been another area of focus for the Cluster mission, which for the last decade and a half has been attempting to explore how these ions are lost, where they come from, and the like. As Philippe Escoubet, ESA’s Project Scientist for the Cluster mission, put it:

“In essence, we need to figure out how cold plasma ends up at the magnetopause. There are a few different aspects to this; we need to know the processes involved in transporting it there, how these processes depend on the dynamic solar wind and the conditions of the magnetosphere, and where plasma is coming from in the first place – does it originate in the ionosphere, the plasmasphere, or somewhere else?“

The reasons for understanding this are clear. High energy particles, usually in the form of solar flares, can pose a threat to space-based technology. In addition, understanding how our atmosphere interacts with solar wind is also useful when it comes to space exploration in general. Consider our current efforts to locate life beyond our own planet in the Solar System. If there is one thing that decades of missions to nearby planets has taught us, it is that a planet’s atmosphere and magnetic environment are crucial in determining habitability.

Within close proximity to Earth, there are two examples of this: Mars, which has a thin atmosphere and is too cold; and Venus, who’s atmosphere is too dense and far too hot. In the outer Solar System, Saturn’s moon Titan continues to intrigue us, mainly because of the unusual atmosphere. As the only body with a nitrogen-rich atmosphere besides Earth, it is also the only known planet where liquid transfer takes place between the surface and the atmosphere – albeit with petrochemicals instead of water.

Moreover, NASA’s Juno mission will spend the next two years exploring Jupiter’s own magnetic field and atmosphere. This information will tell us much about the Solar System’s largest planet, but it is also hoped to shed some light on the history planetary formation in the Solar System.

In the past fifteen years, Cluster has been able to tell astronomers a great deal about how Earth’s atmosphere interacts with solar wind, and has helped to explore magnetic field phenomena that we have only begun to understand. And while there is much more to be learned, scientists agree that what has been uncovered so far would have been impossible without a mission like Cluster.

Further Reading: ESA