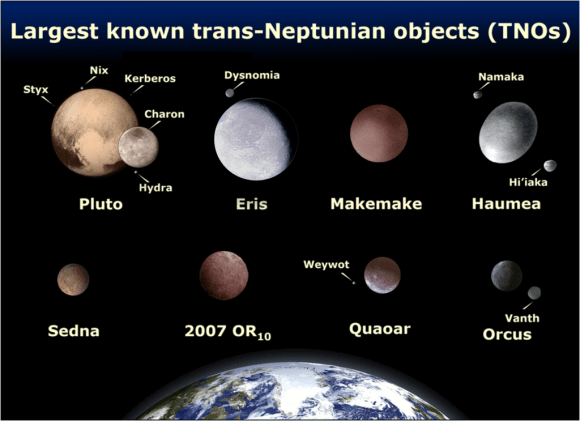

Over the course of the past decade, more and more objects have been discovered within the Trans-Neptunian region. With every new find, we have learned more about the history of our Solar System and the mysteries it holds. At the same time, these finds have forced astronomers to reexamine astronomical conventions that have been in place for decades.

Consider 2007 OR10, a Trans-Neptunian Object (TNO) located within the scattered disc that at one time went by the nicknames of “the seventh dwarf” and “Snow White”. Approximately the same size as Haumea, it is believed to be a dwarf planet, and is currently the largest object in the Solar System that does not have a name.

Discovery and Naming:

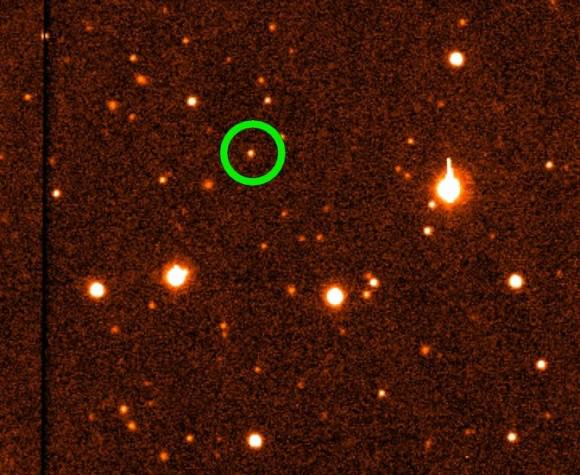

2007 OR10 was discovered in 2007 by Meg Schwamb, a PhD candidate at Caltech and a graduate student of Michael Brown, while working out of the Palomar Observatory. The object was colloquially referred to as the “seventh dwarf” (from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs) since it was the seventh object to be discovered by Brown’s team (after Quaoar in 2002, Sedna in 2003, Haumea and Orcus in 2004, and Makemake and Eris in 2005).

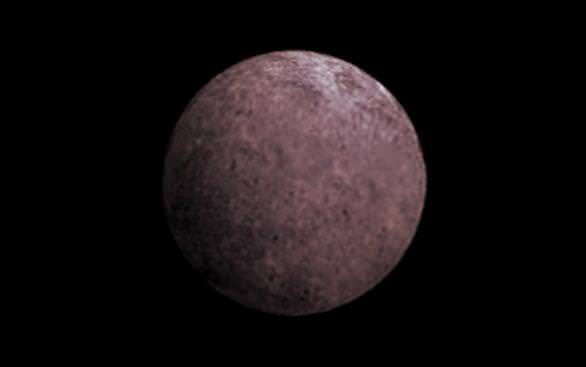

At the time of its discovery, the object appeared to be very large and very white, which led to Brown giving it the other nickname of “Snow White”. However, subsequent observation has revealed that the planet is actually one of the reddest in the Kuiper Belt, comparable only to Haumea. As a result, the nickname was dropped and the object is still designated as 2007 OR10.

The discovery of 2007 OR10 would not be formally announced until January 7th, 2009.

Size, Mass and Orbit:

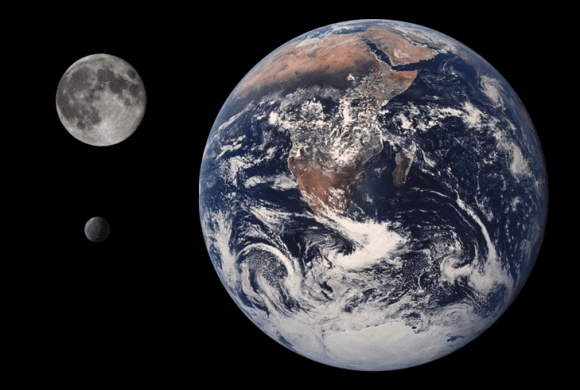

A study published in 2011 by Brown – in collaboration with A.J. Burgasser (University of California San Diego) and W.C. Fraser (MIT) – 2007 OR10’s diameter was estimated to be between 1000-1500 km. These estimates were based on photometry data obtained in 2010 using the Magellan Baade Telescope at the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile, and from spectral data obtained by the Hubble Space Telescope.

However, a survey conducted in 2012 by Pablo Santos Sanz et al. of the Trans-Neptunian region produced an estimate of 1280±210 km based on the object’s size, albedo, and thermal properties. Combined with its absolute magnitude and albedo, 2007 OR10 is the largest unnamed object and the fifth brightest TNO in the Solar System. No estimates of its mass have been made as of yet.

2007 OR10 also has a highly eccentric orbit (0.5058) with an inclination of 30.9376°. What this means is that at perihelion, it is roughly 33 AU (4.9 x 109 km/30.67 x 109 mi) from our Sun while at aphelion, it is as distant as 100.66 AU (1.5 x 1010 km/9.36 x 1010 mi). It also has an orbital period of 546.6 years, which means that the last time it was at perihelion was 1857 and it won’t reach aphelion until 2130. As such, it is currently the second-farthest known large body in the Solar System, and will be farther out than both Sedna and Eris by 2045.

Composition:

According to the spectral data obtained by Brown, Burgasser and Fraser, 2007 OR10 shows infrared signatures for both water ice and methane, which indicates that it is likely similar in composition to Quaoar. Concurrent with this, the reddish appearance of 2007 OR10 is believed to be due to presence of tholins in the surface ice, which are caused by the irradiation of methane by ultraviolet radiation.

The presence of red methane frost on the surfaces of both 2007 OR10 and Quaoar is also seen as an indication of the possible existence of a tenuous methane atmosphere, which would slowly evaporate into space when the objects are closer to the Sun. Although 2007 OR10 comes closer to the Sun than Quaoar, and is thus warm enough that a methane atmosphere should evaporate, its larger mass makes retention of an atmosphere just possible.

Also, the presence of water ice on the surface is believed to imply that the object underwent a brief period of cryovolcanism in its distant past. According to Brown, this period would have been responsible not only for water ice freezing on the surface, but for the creation of an atmosphere that included nitrogen and carbon monoxide. These would have been depleted rather quickly, and a tenuous atmosphere of methane would be all that remains today.

However, more data is required before astronomers can say for sure whether or not 2007 OR10 has an atmosphere, a history of cryovolcanism, and what its interior looks like. Like other KBOs, it is possible that it is differentiated between a mantle of ices and a rocky core. Assuming that there is sufficient antifreeze, or due to the decay of radioactive elements, there may even be a liquid-water ocean at the core-mantle boundary.

Classification:

Though it is too difficult to resolve 2007 OR10’s size based on direct observation, based on calculations of 2007 OR10’s albedo and absolute magnitude, many astronomers believe it to be of sufficient size to have achieved hydrostatic equilibrium. As Brown stated in 2011, 2007 OR10 “must be a dwarf planet even if predominantly rocky”, which is based on a minimum possible diameter of 552 km and what is believed to be the conditions under which hydrostatic equilibrium occurs in cold icy-rock bodies.

That same year, Scott S. Sheppard and his team (which included Chad Trujillo) conducted a survey of bright KBOs (including 2007 OR10) using the Palomar Observatory’s 48 inch Schmidt telescope. According to their findings, they determined that “[a]ssuming moderate albedos, several of the new discoveries from this survey could be in hydrostatic equilibrium and thus could be considered dwarf planets.”

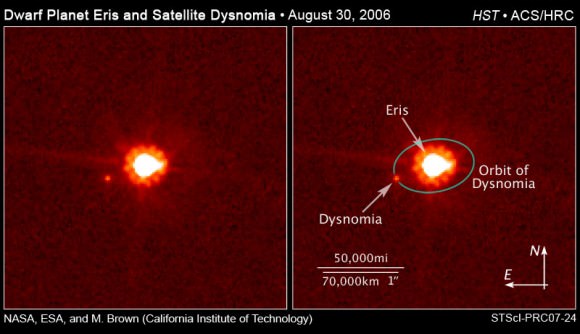

Currently, nothing is known of 2007 OR10’s mass, which is a major factor when determining if a body has achieved hydrostatic equilibrium. This is due in part to there being no known satellite(s) in orbit of the object, which in turn is a major factor in determining the mass of a system. Meanwhile, the IAU has not addressed the possibility of accepting additional dwarf planets since before the discovery of 2007 OR10 was announced.

Alas, much remains to be learned about 2007 OR10. Much like it’s Trans-Neptunian neighbors and fellow KBOs, a lot will depend on future missions and observations being able to learn more about its size, mass, composition, and whether or not it has any satellites. However, given its extreme distance and fact that it is currently moving further and further away, opportunities to observe and explore it via flybys will be limited.

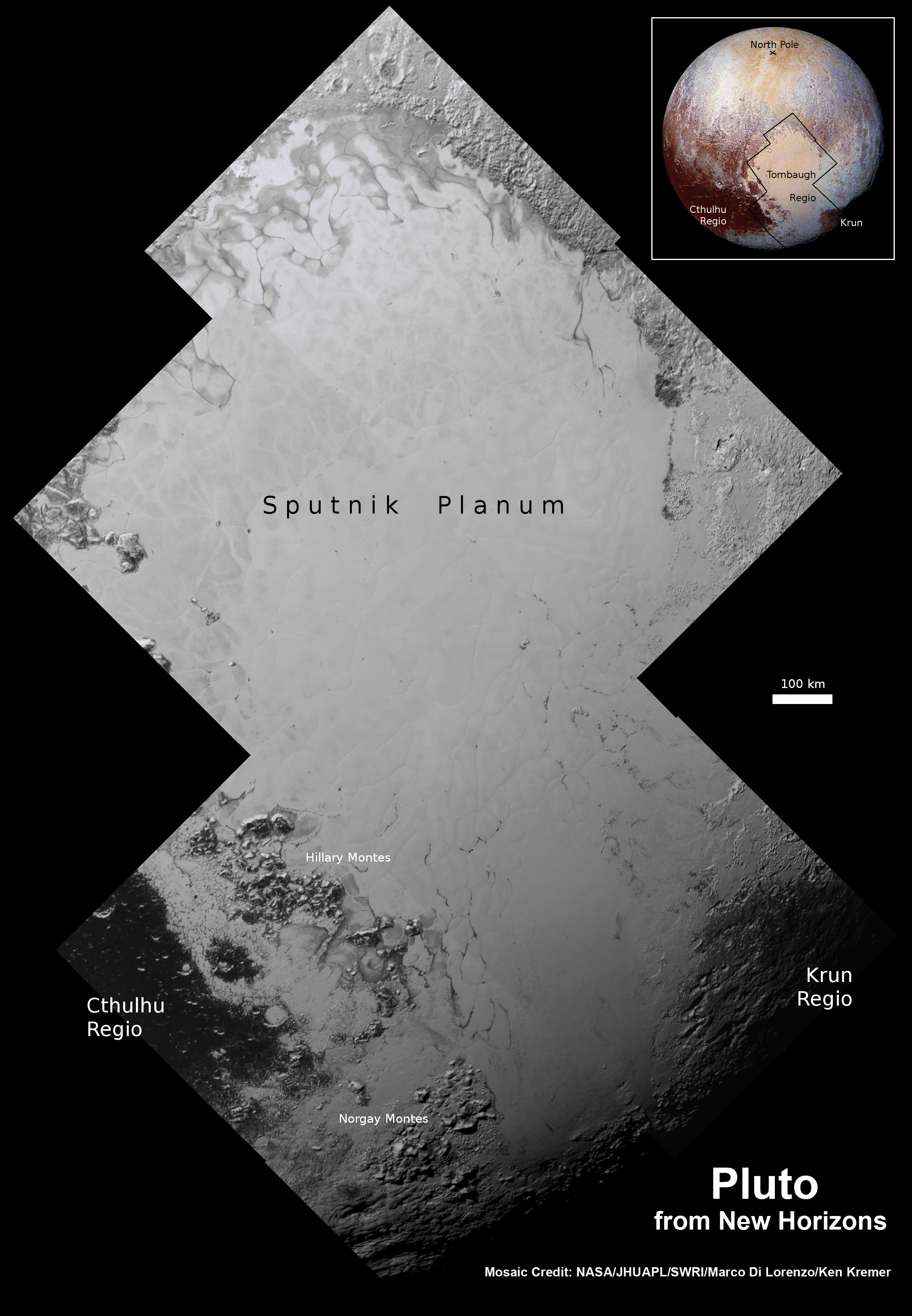

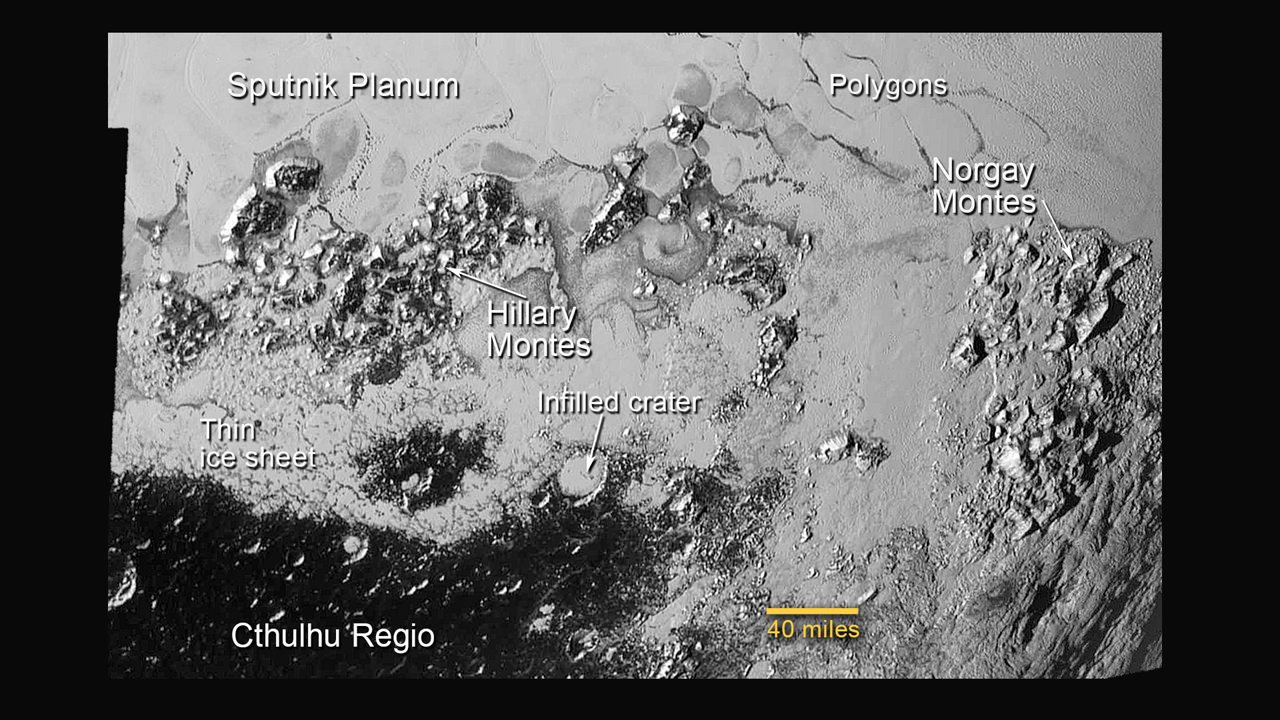

However, if all goes well, this potential dwarf planet could be joining the ranks of such bodies as Pluto, Eris, Ceres, Haumea and Makemake in the not-too-distant future. And with luck, it will be given a name that actually sticks!

We have many interesting articles on Dwarf Planets, the Kuiper Belt, and Plutoids here at Universe Today. Here’s Why Pluto is no longer a planet and how astronomers are predicting Two More Large Planets in the outer Solar System.

Astronomy Cast also has an episode all about Dwarf Planets titled, Episode 194: Dwarf Planets.

For more information, check out the NASA’s Solar System Overview: Dwarf Planets, and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Small-Body Database, as well as Mike Browns Planets.