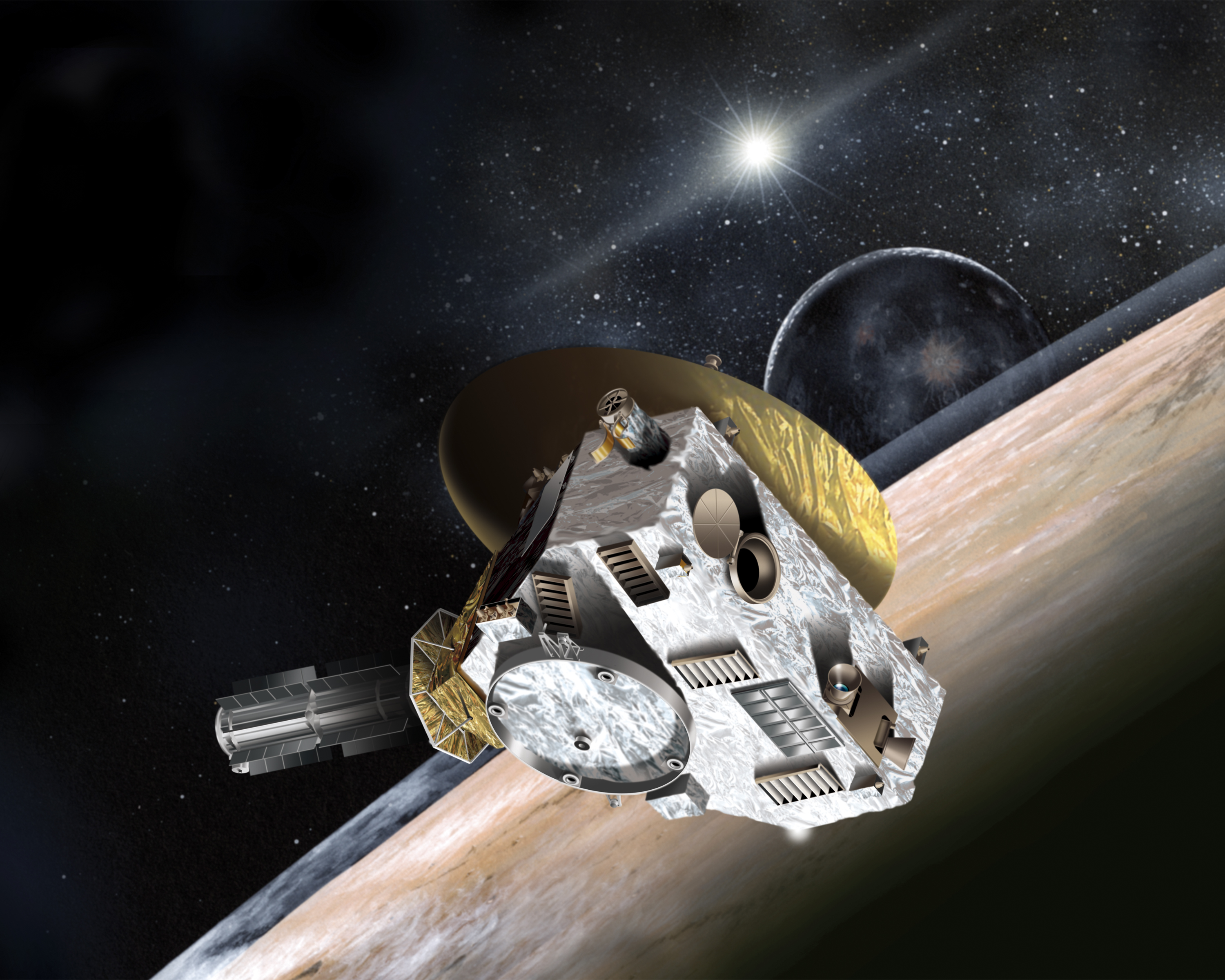

Artist’s concept shows the New Horizons spacecraft during its 2015 encounter with Pluto and its moon, Charon. Credit: JHUAPL/SwRI

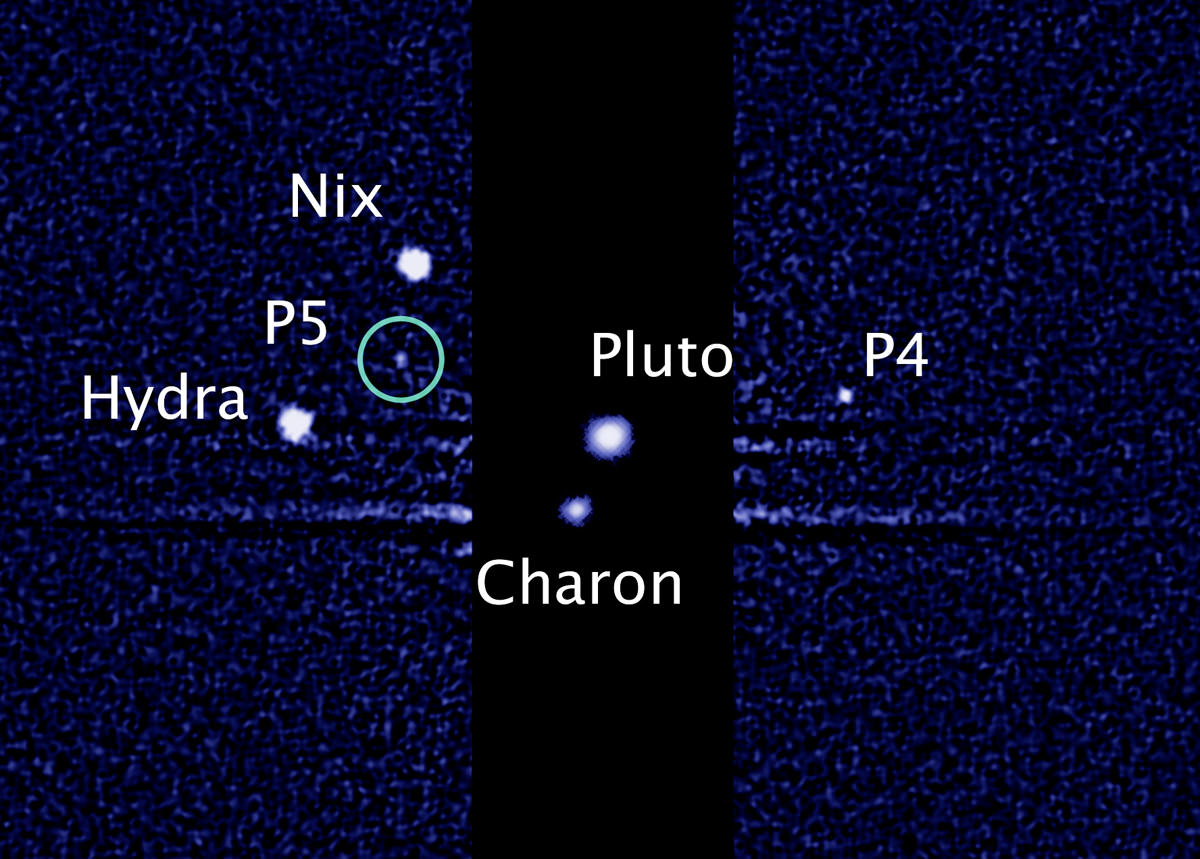

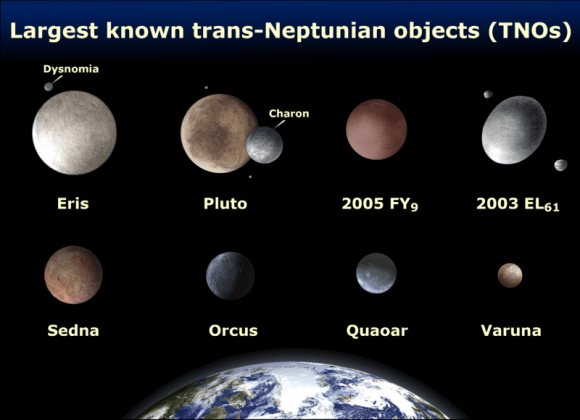

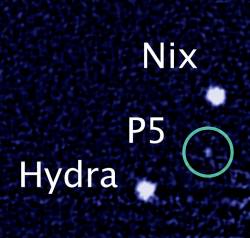

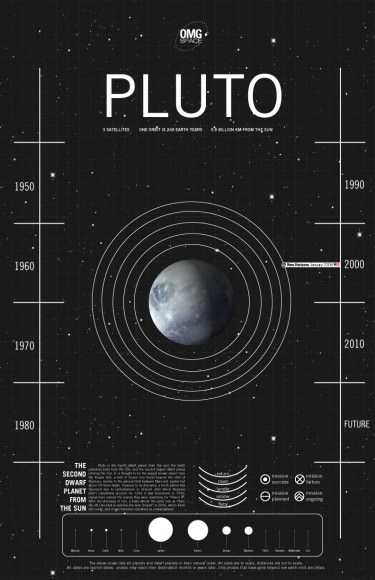

Since the New Horizons spacecraft left Earth back in 2006, there are a few things we know about the Pluto system now that we didn’t know then. For instance, it was discovered Pluto has two additional small moons – P4 and P5 — and Alan Stern, New Horizons Principal Investigator, said Pluto may have a large system of moons to be discovered as the spacecraft gets closer. There are also comets, possibly more dwarf planets and other objects out in the Kuiper Belt region where Pluto orbits.

“That’s exciting,” Stern said, “but this is a mixed story.”

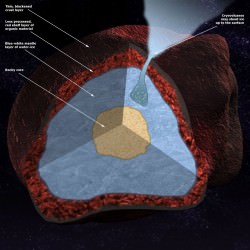

Stern told Universe Today that while the spacecraft possibly could come upon an undiscovered moon or Kuiper Belt Object and they would have to alter course, the biggest issue is tiny debris which may be coming from impacts on the smaller moons.

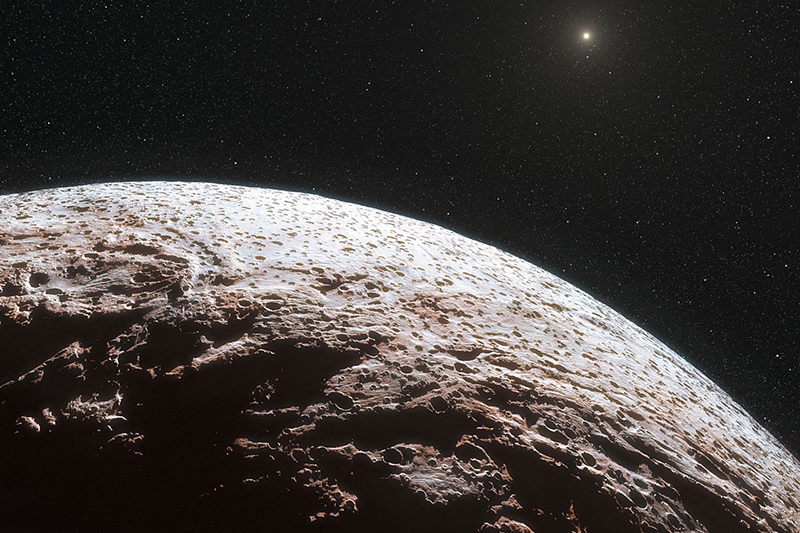

“We could have 100 moons the size of P4 and they would not be a significant hazard,” Stern said via email. “The hazard is from ejecta coming off these satellites when they are cratered, because the ejecta escapes their feeble gravity and gets into orbit around Pluto.”

At a press conference at the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences meeting, Stern said that with all the debris in the Kuiper Belt, objects are definitely getting impacted. “If hits occur on Pluto and Charon, they have enough gravity that ejecta just flies across the planet and creates secondary craters. But the ejecta on smaller moons puts shards and debris into the Pluto system.”

Stern said the ejecta speeds from these moons would be comparable to orbital speeds. That means the debris can orbit at any inclination, and there could be a cloud of debris around the system, creating a hazard for the spacecraft.

This worries Stern and his team.

“My spacecraft is going very fast and even a strike from something as small as a BB would be fatal,” he said. “There’s almost no place the spacecraft could get hit and it would be OK.”

Stern said current knowledge of the density of debris of the system can’t prove the spacecraft won’t get hit, and they won’t be able to find out more until they get closer.

“We’re going somewhere new and have no direct evidence of debris that could pose an impact hazard,” he said. “We don’t know what we are going to find and we might have to change our course.”

Stern and his team are looking at some alternative plans, and developing them now is crucial.

“When we plan an encounter for a mission like this, it literally takes tens of thousands of man-hours by experts to put that sequence together and test it,” he said. “We have to plan them now in order to complete that planning. We can’t complete them in the last couple of months or weeks.”

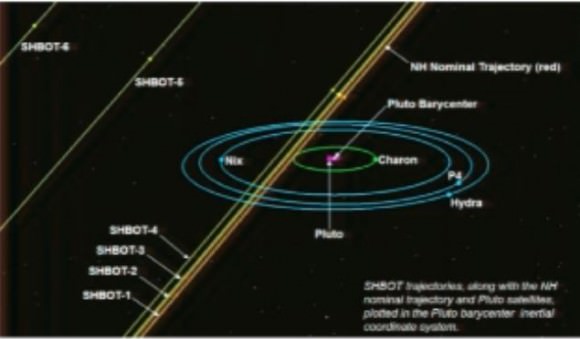

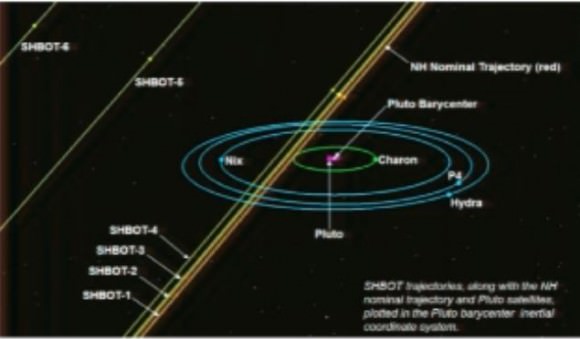

The plans being considered are called SHBOT: Safe Haven Bail Out Trajectory. They currently have nine different possible trajectories, depending on what they find as they get closer.

Screenshot from Stern’s presentation, depicting the nine SHBOT trajectories.

The team is also using every available tool — including sophisticated computer simulations of the stability of debris orbiting Pluto, giant ground-based telescopes, stellar occultation probes of the Pluto system, and even the Hubble Space Telescope — to search for debris in orbit.

Stern told Universe Today that they use the cameras on New Horizons itself every summer when they “wake up” the spacecraft. “LORRI (Long Range Reconnaissance Imager) has already seen Pluto for about 6 years!” he said, “But we won’t pass HST resolution till we’re about 10 weeks out, in April 2015. That’s when we turn on the heavy effort to look for more moons, rings, etc.”

They are looking at the pluses and minuses for each of the plans so they can be tested and be just as “bullet-proof” as the original, nominal flight plan.

In addition to saving the spacecraft, these alternative trajectories also need to preserve the science mission as much as possible. Most of the alternate courses bring the spacecraft farther away from the Pluto system, but one actually brings it closer to Charon, as the path there may be clearer there because of Charon’s gravity and clearing effect.

The spacecraft will start science observations in January 2015, with closest approach to the system currently set for on July 14, 2015 (“Bastille Day,” Stern said, “when we storm the gates of the Pluto system!”)

During the final 50 days of approach, when the spacecraft is taking pictures and sending them back to Earth to be analyzed, the team may discover something and have to fire the spacecraft engines, putting them on one of the SHBOT trajectories. But the last opportunity to actually change course is 10 days before encounter.

“After that we are in too close and we would run out of fuel and not complete the maneuver,” Stern said.

So, while the Mars Science Laboratory team had “Seven minutes of terror” during the perilous landing on Mars, Stern said they have something similar. “We don’t have seven minutes of terror; we have seven weeks of suspense.”

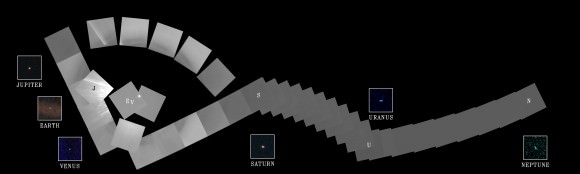

It was the unique perspective above provided by Voyager 1 that inspired Carl Sagan to first coin the phrase “Pale Blue Dot” in reference to our planet. And it’s true… from the edges of the solar system Earth is just a pale blue dot in a black sky, a bright speck just like all the other planets. It’s a sobering and somewhat chilling image of our world… but also inspiring, as the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft are now the farthest human-made objects in existence — and getting farther every second. They still faithfully transmit data back to us even now, over 35 years since their launches, from 18.5 and 15.2 billion kilometers away.

It was the unique perspective above provided by Voyager 1 that inspired Carl Sagan to first coin the phrase “Pale Blue Dot” in reference to our planet. And it’s true… from the edges of the solar system Earth is just a pale blue dot in a black sky, a bright speck just like all the other planets. It’s a sobering and somewhat chilling image of our world… but also inspiring, as the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft are now the farthest human-made objects in existence — and getting farther every second. They still faithfully transmit data back to us even now, over 35 years since their launches, from 18.5 and 15.2 billion kilometers away.